Amazing Amaranth

This article offers info on how to grow the underrated and underutilized ancient food crop that is Amaranth, exploring it’s many health benefits and offering some recipe ideas to enjoy your harvests

It is very nutritious, versatile in the kitchen and fun to grow in the garden.

Both the leaves and the seeds are edible and highly nutritious.

Some varieties have even been selectively bred to produce succulent edible stems as well! Talk about a versatile garden crop, it can potentially produce three crops from one plant!

Amaranth is easy to grow on a small scale and certain varieties (like the Golden Giant Amaranth -Amaranthus hypochondriacus- shown in the pictures below) offer a surprising amount of ancient ‘grain’ (edible seeds that can be used in the place of and/or along side wheat in baking recipes) even with modest square footage. Healthy plants can produce up to one pound of "grain" per flower head!

In the Caribbean “Calaloo” Amaranth was bred to produce luscious green leaves that are used in the place of spinach to provide hearty nutrition to stews, stirfries and soups.

In Asia, “Chinese Multicolored Spinach” Amaranth was bred to produce delicious (and antioxidant rich) leaves that are eaten raw, stir fried, or steamed.

It is known as bireum In Korea and as xian cai in China. Recent research has shown that amaranth in Asia is identical to that of amaranth in the Americas, and has been proven to have existed in Asia for millennia. The presence of amaranth in Asia is considered a living piece of evidence that pre-Columbian transatlantic trade indeed happened. This is by far the most tender and sweetest amaranth for edible greens, making for vibrant and delicious salad. The young leaves are a perfect spinach substitute; the intricately colored leaves are juicy and succulent. This is the go-to “green” for midsummer when all others have bolted, and can be harvested just 30-40 days from sowing.

Other varieties produce leaves and seeds high in the antioxidant called anthocyanin which not only offer a long list of their own health benefits but can also add a nice ornamental flare to your front yard garden.

Hopi Red Dye Amaranth (Amaranthus cruentus) which is shown growing in our garden in the pictures below, was originally developed and grown as a dye plant by the southwestern Hopi Nation. For more information on the cultural origins and modern day relevance of heirloom varieties like Hopi Red Dye Amaranth: https://www.nativeseeds.org/blogs/blog-news/giving-voice-to-seeds-hopi-red-dye-amaranth

This variety has the highest levels of anthocyanin expression of any amaranth known. Plants reach 4-6 feet high and cut a most striking figure in the garden!

The Hopi people use the deep red flower bract as a natural dye to color their world-renowned piki bread.

The brilliant red dye rendered from its flowers can be used in craft projects and as a natural food dye -- the possibilities are endless. The young leaves are excellent sautéed. The seeds can be popped or ‘puffed’ in a hot pan (like one would pop corn kernels) for easy snacking and/or adding to baked goods in the place of poppy seeds.

You can plant Hopi Red Dye Amaranth in your front yard/ornamental garden and no one would ever suspect it’s many culinary uses. So for those of you that live in cookie cutter landscape world (where municipal laws and whiney programmed neighbors would try to prevent you from growing a food garden in your front yard) this variety may prove as a useful ally ;)

In the section of the article below relating to harvesting I will share a couple helpful methods you can use on the residential to small farm scale for separating Amarnath seeds from the chaff relatively quickly and easily (without high tech or expensive tools).

Not only are the seeds edible (and extremely nutritious/high in antioxidants) and so they make for a great winter food, the seeds can also be sprouted at any time of the year to be enjoyed as either sprouts or microgreens!

Amarnath sprouts are fantastic on salads and sandwiches.

It is a beautiful plant and so some people grow it as an ornamental but there is no reason why it cannot serve both the purpose of aesthetic beauty and serving as a staple food crop at the same time 🙂

History of Amaranth

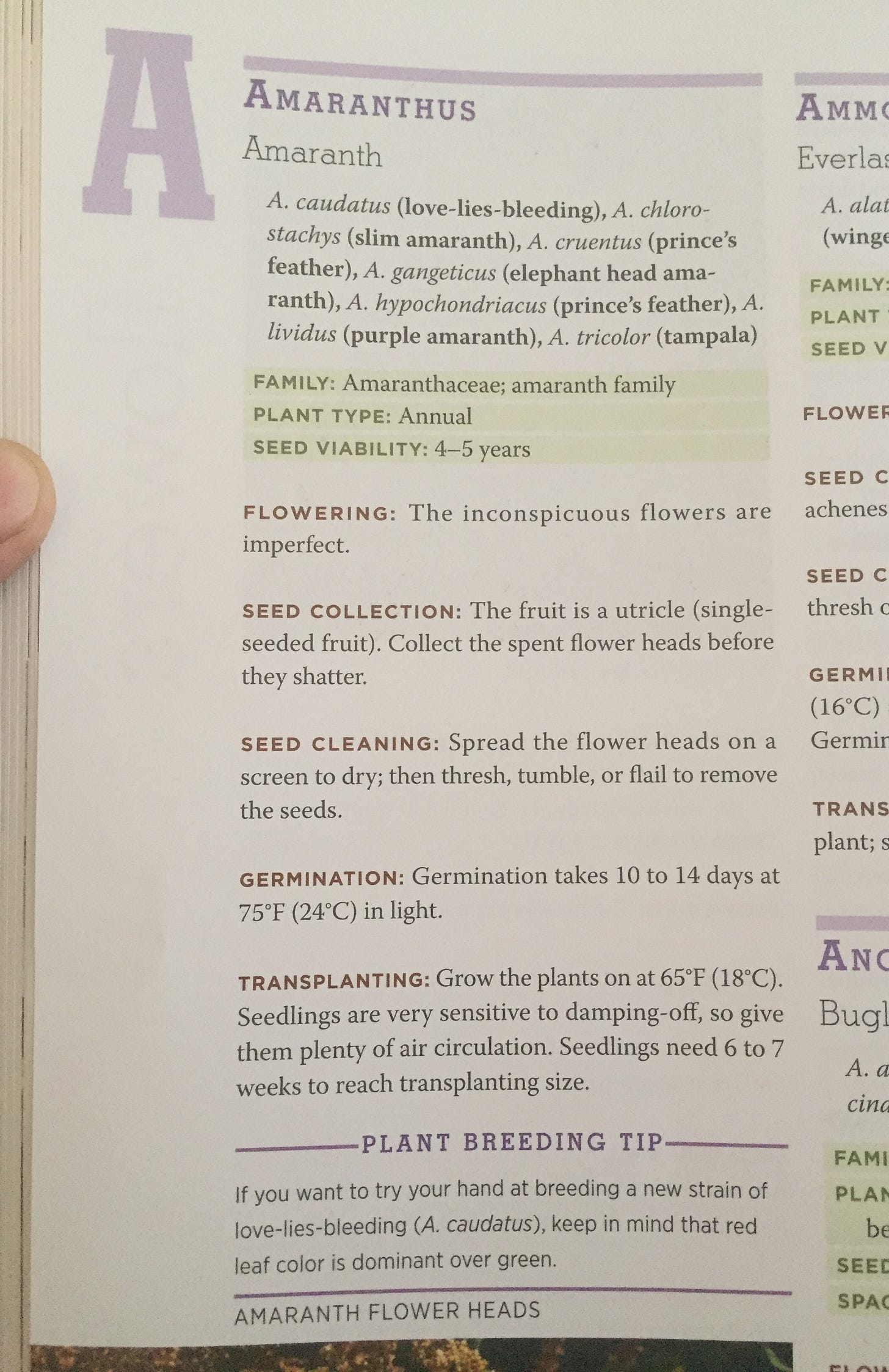

Amaranthus is a dicotyledonous pseudocereal and one of the New World’s oldest crops, having originated in Mesoamerica. The family Amaranthaceae is generally considered as the “amaranth family.” The word Amaranthus is basically derived from the Greek word “anthos” (flower) which means everlasting or unwilting.

Although amaranth has only recently gained popularity as a health food, this ancient "grain" has been a dietary staple in certain parts of the world for millennia.

Amaranth is a group of more than 60 different species of grains that have been cultivated for about 8,000 years.

These grains were once considered a staple food in the Inca, Maya and Triple Alliance (aka “Aztec”) civilizations. Amaranth was known to the the people of the Triple Alliance (Nahuatl speaking) as huâuhtli.

When Cortez and his Spaniards landed in the New World in the sixteenth century, they immediately began fervent, forceful and violent attempts to convert the indigenous peoples to Christianity. One of their first moves was to outlaw foods involved in “heathen” festivals and religious ceremonies, amaranth included. Although severe punishment was handed to anyone found growing or possessing amaranth, thankfully the complete eradication of this culturally important, fast-growing, drought tolerant, extremely nutritious and very prevalent plant proved to be impossible.

Huaútli was banned by the invading Spanish Empire led by Hernán Cortez and the Catholic Church in 1519.

Today huaútli is most commonly known as amaranth, a super-food gaining worldwide recognition as a high-protein plant edible that could easily figure into the solution for world hunger. Although not considered a grain, the tiny amaranth seeds contain eight to nine grams of protein in a one cup serving, offering a nutritionally complete plant food that has all the essential amino acids needed by the human body, without gluten.

Together with corn, beans and chia, amaranth was a key part of the near-perfect core diet of Mesoamerican Indian civilizations, and a tribute item demanded by the Aztecs. But the invading conquerors prohibited its cultivation and consumption calling it an ungodly pagan food, something full of sin. So for hundreds of years under the rule of Spain, amaranth all but disappeared from the face of the earth except in the highlands of Oaxaca and to the south among the Mayan people where its cultivation most probably began some 10,000 years ago.

Amaranth was a primary crop not only important as food, but central to the spiritual and ritual life of Mesoamerican indigenous civilizations; its precious seeds and leaves were nutritious and therapeutic; it was an offering to the gods as well as the ingredient used by midwives to bathe newborn babies; it was mixed into a paste and transformed into miniature reproductions of the child’s future attributes: a bow, an arrow, the hunter’s instruments; or perhaps a flower or an animal spirit-guide. Amaranth was not only food and medicine for the body it was also valued as a divine plant.

But more importantly, it was used in religious rituals offered to certain deities, as a dish called tzoali, a delicacy of popped amaranth and sweet magüey blue agave syrup or honey, mixed together and shaped. Today those same tzoali are called alegrías and can be found in bakeries and stores throughout Mexico and in the Southwestern United States, or anywhere Mexican culture and cuisine flourish.

Yet when Spain invaded the Americas, they soon criminalized the cultivation of amaranth, as they did with the quinoa plant in South America. In doing so they banned the cultivation of one the world’s best sources of plant protein. The Spanish Empire imposed the most cruel and uncompromising punishments for growing huaútli, including cutting off the hands of those who dared to plant it.

So why did this beautiful nutritious and mystical plant elicit such a savage response from the invaders? This atrocity was most likely triggered by the importance of amaranth both in the people’s diet and in their spiritual life, a plant rightly held in high esteem.

Upon their arrival, the Catholic priests were horrified to find that amaranth was considered a deity and used in religious ceremonial rituals. It was consumed and mixed, according to some sources, with the blood of people who were sacrificed, and was perhaps a tad too close to the religious ceremonial ritual of the holy Eucharist, the Catholic ritual that consecrates the body and blood of Christ and is also eaten. But the Eucharist is of course not considered savagery by the church. To the contrary, it is considered a blessed sacrament.

As many scholars have noted, amaranth was an important part of the diet of warriors as well as a sacred plant that came into the cross-hairs of the Church’s war against paganism. So the more likely truth is that the criminalization of amaranth was both a military strategy intended to weaken the Aztec people allowing for an easier conquest. It was also a brutal tactic used by Catholic Church to eliminate any practices or evidence of an indigenous religion. Like all warriors, the Mexica Eagle Guild Warriors ate amaranth and were responsible for fighting off and killing about 80% of the Spanish invaders who died in battle, despite their iron swords and their use of horses and dogs as weapons of war. So it was urgent for the Empire and the Church to weaken and crush the masses of people and their warriors by any means necessary.

Despite its near extinction, today’s amaranth, the hardy survivor huaútli, can be found in contemporary cooking from granola to pancakes and is once again taking it’s place as an important plant food in defiance of its illicit past.

Diverse varieties of amaranth were cultivated all the way to the lands of the Inca people in the South American Andes, where it is consumed to this day. High in protein and the essential amino acid, lysine, amaranth found its way to Europe and is even consumed in India where it is known as rajeera, or the king’s grain.

How ironic that this offering of forbidden toasted amaranth seeds, held together by the sweetness of agave nectar and honey, made round in the shape of the sun and the circle of life, should survive to be called alegría, happiness or joy. No blood this time. Plenty of that was spilled by the Spanish invaders.

Since then this extremely valuable crop has found it’s way to four different continents where unique cultures and climates have created interesting varieties that offer myriad uses in the kitchen and beyond (a small portion of which were described above). Currently it is widely cultivated and consumed throughout India, Nepal, China, Indonesia, Malaysia, and the Philippines; whole of Central America, Mexico; and Southern and Eastern Africa (and Canada, well at least in our garden/kitchen! ;) )

The fact that Amaranth was irrepressible and resilient in the face of an imperialistic empire attempting to eradicate it (and the peoples that depended on it as a food crop and cultural pillar) makes me see Amaranth as a noble food crop. We live in times when a new kind of global imperialistic colonial empire (a transnational corporatocracy) is attempting to invade, dominate, control, commodify and assimilate a multitude of different peoples (and myriad non-human beings that we share this Earth with). Thus, I feel that through teaming up (and learning from) our noble elder species (like Amaranth) we can effectively resist the totalitarian corporatocracy’s militaristic attack on our cultures, communities and ecosystems and embody resilience (as Amaranth did) to weather the storm ahead and emerge on the other side intact and capable of planting the seeds for something beautiful to take root.

A versatile addition to the ornamental and/or kitchen garden

Amaranth is quite adaptable, disease-free and a drought-tolerant plant. It thrives in rich soil—as long as it is well drained—but will, once established, produce abundant harvests under dry conditions.

The wild relatives of both amaranth and quinoa have long been familiar to North American gardeners and are often called by the same name of pigweed. The pigweed that is related to quinoa is also called lamb's-quarters (Chenopodium album), while the ancestor of amaranth is known as red-rooted pigweed or wild amaranth (Amaranthus retroflexus). Both pigweeds have the amazing ability to flower and go to seed at any stage of their growth and both will cross with their cultivated progeny. The grower who wants to maintain a 'pure' strain of amaranth must therefore pay close attention to weeds.

As described above, there is tall amaranth, short amaranth, amaranth that is best for it's leaves, some that is grown for it's grain, and some that makes the most amazing decoration with cascading flowers like colourful waterfalls.

How to grow amaranth:

Amaranth is a warm season crop that requires full sun. Best germination occurs when soil temperatures range from 65 to 75°F (18-24°C). For southern Canada and the northern U.S., this usually means May or early June planting. When planting your garden, keep in mind that happy Golden Giant Amaranth plants can easily grow 9 foot tall.

If there is enough water to get the crop established (helping the roots to dig in deep), it can be grown with very little water. It can generate seeds with up to 40 days of no rain. Besides being drought tolerant, Amarnath offers further climate adaptability as a garden crop since early frost isn’t a problem. It can be planted late and autumn frost is actually helpful because it dries the seed, preparing it to be harvested.

Amaranth is best when sown about the same time as corn, around here that would be mid May to early June. The seeds are very fine, if planting with a specific arrangement in mind I usually plant them by making a shallow line in the soil, scattering the seeds, and nudging a light layer of soil over top. Later on, I'll thin the young plants (eating the young ones in stir fry or salad) so that the largest plants remain, usually one or two per foot.

The video clip linked below shows one of our self seeded Golden Giant Amaranth patches growing in a raised bed built over an inverted hugelkultur (aka 'dead wood swale') thriving on only rain water (2019). Many other edible plants self seeded in that bed as well and we added some peppers, tomatoes, potatoes and sweet potatoes on the sunny edges of the raised bed which all produced a significant harvest of their own (in addition to a huge Amaranth seed harvest).

If planted in a garden space with rich fertile soil, Amarnath is a wonderful candidate for companion planting in order to create highly productive garden beds that produce multiple crops in the same square footage.

You can plant beans or peas to climb up your amaranth stalks and something else low that helps to shade the soil (in a similar way to how the First Nation peoples of what is now called Canada and the United States grew corn, beans and squash as part of their Three Sisters Companion Planting Cultivation Technique.

Aditionally, it is even possible to grow root and tuber crops in the same bed as Amarnath (given you provide enough organic matter and depth of soil). The images below exemplify one expression of this potential where we grew Sweet Potatoes underneath our Amaranth plants (in the same square footage). The vines reaches outside the raised bed (and also climbed up some of the Amaranth stalks) to get sunlight and the deep fertile soil provided enough nutrients for both crops.

Alternatively you can add a nice layer of compost or rich top soil to your intended growing space, rake it out so its nice and fluffy, throw sow a few pinches of seeds evenly spread out and then lightly rake the seeds in (or leave on the soil surface).

I have had success with both of the more hands off methods. Amaranth in our garden will self sow (from seeds dropped the previous year) germinate and grow without rain or irrigation, so long as it has a happy helping of morning dew. I just thin them as needed as they grow. Once mature flower heads have set and you are going to harvest seed for cooking or storing leave a few of the lower sprigs of the best flower heads so the plants can self-seed, chop and drop the stalks and remaining leaves and allow to decompose in place.

Here is the video that got me interested in growing Amaranth in the first place. In the video, Matt Powers (aka The Permaculture Student) talks about growing Amaranth in a hot and dry climate, separating the seeds from the chaff (in a slightly different way than I described below) and using a “Chop and Drop” technique to nurture and protect the soil for future harvests.

All of Matt’s Books are currently on sale at his website! https://www.thepermaculturestudent.com/shop I highly recommend his permaculture books as I have found them to be instrumental in optimizing my gardening methods to minimize the work required to get huge harvests (while also giving back to the Earth).

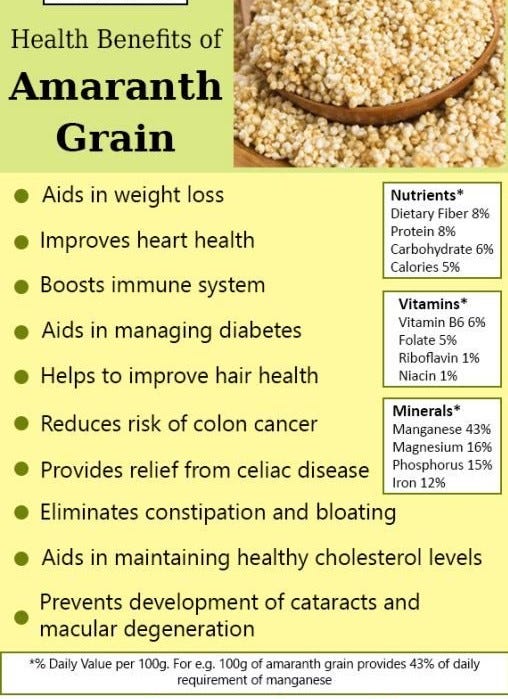

Health Benefits of Amaranth

Amaranth is classified as a pseudocereal, meaning that it’s not technically a cereal grain like wheat or oats, but it shares a comparable set of nutrients and is used in similar ways.

Amaranth is an important ‘ancient grain’ because it is gluten-free and contains about twice the crude protein of wheat, rice, and maize and is high in fiber (8%), lysine, iron, magnesium, and calcium.

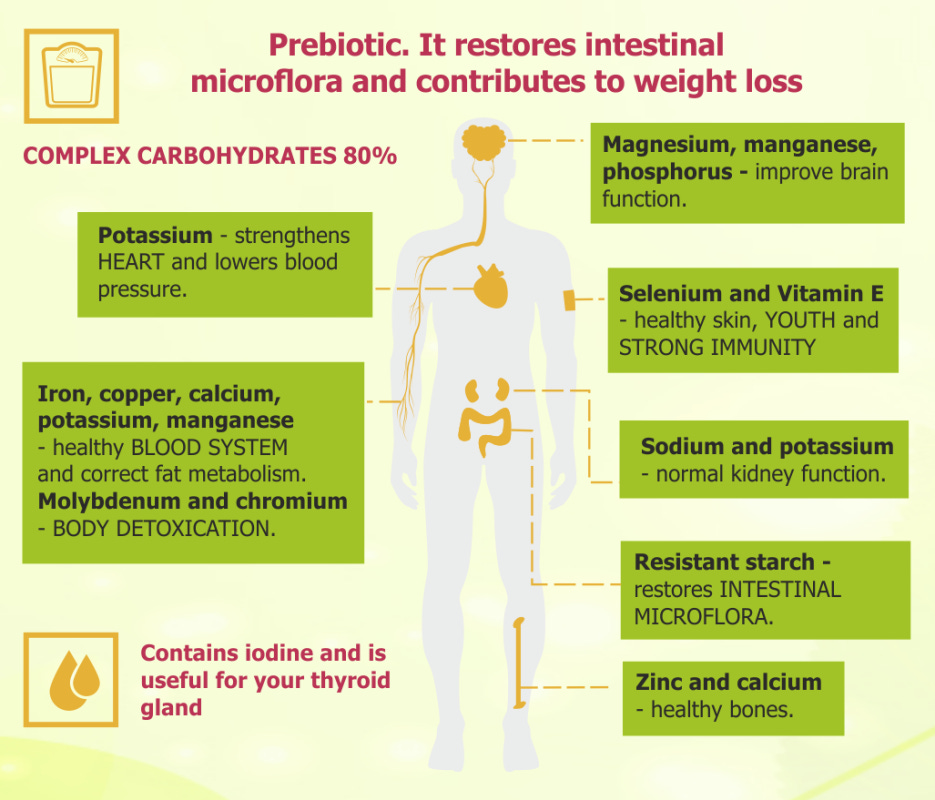

Amaranth is a good source of manganese, magnesium, phosphorus, selenium, copper and iron. Amaranth is also high in anti-oxidants. It is especially high in phenolic acids, which are plant compounds that act as antioxidants. These include gallic acid, p-hydroxybenzoic acid and vanillic acid, all of which help protect against diseases like heart disease and cancer.

Due to it’s impressive nutrient profile eating amaranth has been associated with a number of impressive health benefits.

A 2017 review published in Molecular Nutrition and Food Research indicates that the proteins found in amaranth are particularly high in nutritional quality due to the outstanding balance of essential amino acids. Plus, the phytochemicals found in amaranth contribute to its antioxidant and anti-inflammatory effects and allows for the grain’s range of health benefits.

Existing evidence suggests that nutrition, especially staple-based foods such as amaranth, when part of a balanced pattern, contributes with important protein, polyunsaturated fatty acids, minerals (calcium, zinc, iron, magnesium, and manganese, among other minerals), appropriate dietary fiber, vitamins, and antioxidants that mitigates or reduces the risk of several diseases.

Amaranth has an excellent nutrient composition with a high concentration of proteins (13–19%) and bioactive peptides. As a matter of fact, amaranth helps as antihypertensive, antioxidant, antithrombotic, and antiproliferative biological activities, among others. These peptides are encrypted within the proteins, and only after enzymatic digestion or food processing are they released.

The amaranth composition includes carbohydrates, dietary fiber, lipids and proteins, and other important constituents, such as squalene, tocopherols, phenolic compounds, flavonoids, phytates, vitamins, and minerals.

20 Health Benefits Offered By Amaranth:

1. Fights Inflammation:

The anti-inflammatory properties of peptides and oils in amaranth can ease pain and reduce inflammation. This is especially important for chronic conditions where inflammation erodes your health, such as diabetes, heart disease, neurodegenerative diseases and stroke.

You can also use amaranth oil for minor injuries and specific skin conditions. For example, if you trip and sprain your ankle, you can use it to reduce the risk of inflammation.

It is well documented that inflammation is a normal immune response designed to protect the body against injury and infection. If the inflammation process continues in your body, this could contribute and be associated with chronic diseases, such as cancer, diabetes, and autoimmune disorders.

The intake of amaranth could help to avoid diseases caused by inflammation because it has been described that extruded amaranth protein hydrolysates prevented inflammation by the activation of bioactive peptides that reduced the expression of several pro-inflammatory markers [22]. That is the reason why consumption of amaranth grain could help to reduce inflammation [23]. In this context, it is recommended to include amaranth grain in the diet in order to reduce inflammation and may help to prevent chronic diseases derived from inflammation process.

2. Reduces Risk of Developing Cancer:

The same peptides in amaranth that protect against inflammation may also help prevent cancer, a study shows. The antioxidants in amaranth grain may even help protect cells from damage that can lead to cancer.

According to the Cancer Research Institute, cancer is the name given to a collection of related diseases. In all types of cancer, some of the body’s cells begin to divide without stopping and spread into surrounding tissues. Cancer can start almost anywhere in the human body, which is made up of trillions of cells. Normally, human cells grow and divide to form new cells as the body needs them. It happens that when cells grow old or become damaged, they die, and new cells take their place. When cancer develops, however, this orderly process breaks down. As cells become more and more abnormal, old or damaged cells survive when they should die, and new cells form when they are not needed. These extra cells can divide without stopping and may form growths called tumors.

In vitro assay of antiproliferative potential of Amaranthus cruentus aqueous extract on human peripheral blood lymphocytes has been reported by Gandhi et al. [53]. Later on it has been reported that hexane, ethyl-acetate, and methanolic extracts of A. tristis Roxb. showed antiproliferative properties with minimum side effects as determined in human colon adenocarcinoma cell line (COLO-320-DM) [54].

Recently, Peters and Gandhi reported more experimental evidence regarding the antitumor potential of various amaranth leaf extracts using different solvent with significant antitumor potential. These authors stated that leaf extract should further be explored as a novel source of cancer therapy [47].

3. Gluten-Free Flour Option:

Celiac disease is a serious disorder in which eating gluten, a protein found in wheat, barley, and rye, triggers an immune response in the body, causing inflammation and damaging the lining of the small intestine. The damage of the small intestine’s lining causes a poor absorption of some nutrients, diarrhea, fatigue, weight loss, poor memory, joint paint, bloating, and anemia, among other symptoms.

Amaranth isn’t really a grain, and it does not have the sometimes troublesome proteins (aka “anti-nutrients”) you find in wheat, rye, and barley. This makes it the perfect ingredient for various gluten-free recipes.

Amaranth flour can be used as a gluten-free flour option to thicken soups and stews, sauces, and more. It can also be used with other gluten-free flours and gums in baking.

Recently amaranth grain has gained more relevance because it is a gluten-free pseudocereal being an alternative option when cereals, such as wheat, barley, and rye, which do contain gluten, cannot be consumed because they cause food allergies. Amaranth is also an excellent protein choice for a healthier life and better performance for athletes, vegans, vegetarians, and those persons that had acquired allergies or have celiac disease.

Amaranth is an excellent protein source for persons that are non-celiac gluten sensitivity (NCGS) who later on acquire gluten intolerance and also for those that born with celiac disease [40, 41, 42].

4. Amaranth as a cardioprotective

It has been proven that amaranth’s oil can reduce total and bad cholesterol (LDL) increasing good cholesterol as tested in animal models by Berger et al. [28]. Also it has been proven that amaranth affected absorption of cholesterol and bile acids, cholesterol lipoprotein distribution, hepatic cholesterol content, and cholesterol biosynthesis.

The fiber and phytonutrients in amaranth can also lower blood pressure, according to some recent studies. This seed tackles cholesterol, inflammation, and blood pressure, making it an all-around good food for heart health.

5. Protects Against Diet-induced Diabetes

Diabetes is a metabolic disorder where the body does not produce insulin or does not use it efficiently during the body’s ability to process blood glucose.Consequently, it can lead to dangerous complications, including stroke, heart disease, kidney failure, and diabetic retinopathy, among other problems, it has been reported that amaranth grain and oil have an antioxidative effect on streptozotocin-induced diabetic rats [33]; grains and oils used as supplements may be beneficial for correcting hyperglycemia as part of an antioxidant therapy.

Manganese, besides regulating blood glucose, can boost the immune function [34]. Also it is known that manganese is needed in adequate levels to avoid abnormalities in cholesterol levels, skin and bone health [35], and renal health [36]. Another relevant benefit obtained when amaranth is included in diet is that due to its high amount of manganese, it represents a good option for regulating sugar levels. In the organism as manganese helps during gluconeogenesis, in this way, when manganese is obtained in a sufficient amount by consuming amaranth, one can protect against diet-induced diabetes [37].

It has been shown that the influence of dietary therapy which uses sunflower and amaranth oils on parameters of immune reactivity in patients with diabetes mellitus type 2 [38] and the activation of aerobic metabolism by amaranth oil improve heart rate variability both in athletes and patients with diabetes [39].

6. Good Source of Protein:

It has truly remarkable protein content: cup for cup, 28.1 grams of protein compared to the 26.3 grams in oats and 13.1 grams in rice.

Amaranth is a very rich source of protein and essential amino acids.

Also, this protein is highly bioavailable, which means the protein in amaranth is more digestible than other seeds and grains.

Acquiring protein in our diet is one of the most reliable ways to keep our bodies toned, developed, and functioning properly. A 2011 report published in the Food, Science and Technology Journal states that the unusually high levels of plant proteins in amaranth make it an ideal addition to your diet, especially if you want to ensure healthy growth of cells, muscles, tissues, and skin.

7. Has Potent Lysine Properties:

Vegetables and grains are often lacking in this essential amino acid. Luckily, amaranth has a good amount of lysine which helps the body absorb calcium, build muscle, and produce energy.

One of the most desirable elements of amaranth grain is the fact that it features lysine in much larger quantities than other grains (some grains have none at all). Lysine is an essential amino protein for the human body, which makes amaranth a “complete protein”. This is very desirable for human health, as it delivers all the essential amino acids to create usable proteins within the body, thereby optimizing metabolism and ensuring proper growth and development. This is why amaranth grain represents a vital component of the diet for indigenous cultures and for those with limited access to diverse food sources.

8. Fiber Helps with Digestion:

Insufficient fiber consumption could lead to constipation, bloating, and even increased fat storage. Adding foods that are high-fiber like amaranth are a great option. Amaranth is a high fiber food. This makes it filling and helps aid digestive health, cholesterol, blood pressure, and slows the absorption of sugars to let the body keep up with energy production.

Insufficient fiber consumption could lead to constipation, bloating, and even increased fat storage. Adding foods that are high-fiber like amaranth are a great option.

Using amaranth as part of a healthy breakfast can help increase energy and better digestive functions.

9. Minerals for Overall Health:

Amaranth is a very rich source of minerals like calcium, magnesium, and copper. It is also a good source of zinc, potassium, and phosphorus.

These build strong bones and muscles, aid hydration, boost energy, and are vital in thousands of processes throughout the body.

10. Helps pregnant women

Folic acid is the synthesized stable oxidized form of an essential water-soluble B9-complex vitamin that occurs naturally as various folates, usually in reduced form. Folic acid is very important for the development of a healthy fetus. Folic acid can be taken as a supplement tablet and food fortification, while folates are found naturally in foods. Folates play an important role in single-carbon transfer reactions, in several metabolic pathways including the synthesis of purines and pyrimidines, and, hence, in the formation of DNA and RNA. These actions have complex relations with other essential vitamins, especially vitamin B12 [43]. Prior to 1996, the principal food sources for folates were dark green leafy vegetables, organ meats, eggs, and citrus fruits. A severe deficiency of folate manifests as an anemia characterized by many large immature and dysfunctional red blood cells (megaloblasts).

For pregnant women, a folate deficiency can lead to neural tube defects such as spina bifida. A deficiency can also cause defects such as heart and limb malformations. The folate in amaranth helps the body make new cells, specifically by playing a role in copying and synthesizing DNA. There is 88.0 mcg of folate in amaranth grain (see Table 2). Fortification of foods with folate by the FDA has decreased the risk for neural tube defects by 26% [44].

Amaranth is also a good source of many essential vitamins, too, including vitamins A, C, E, K, B5, B6, folate, niacin, and riboflavin. These act as antioxidants, raise energy levels, control hormones, and do much more.

11. Boosts Immune System:

Amaranth may boost immune function according to some studies, probably thanks to it being a good source of many antioxidants and essential vitamins, too, including vitamins A, C, E, K, B5, B6, folate, niacin, and riboflavin.

With high levels of vitamin C, amaranth grain can help boost the overall immune system, as vitamin C stimulates white blood cell production, and can also contribute to faster healing and repair of cells, due to its functional role in the production of collagen.

Some varieties of Amaranth (such as the above mentioned Hopi Red Dye Amaranth, Chinese Multicolored Spinach Amaranth and Pink Beauty Amaranth) contain high concentrations of Anthocyanins.

Anthocyanin bioflavonoids provide protection from DNA damage and lipid peroxidation, plus they have anti-inflammatory effects and help boost production of cytokines that regulate the immune responses. They have also been shown to support hormonal balance by reducing estrogenic activity, help regulate enzyme production that aids nutrient absorption, and strengthen cell membranes by making them less permeable and fragile.

The antioxidants, raise energy levels, control hormones, and do much more.

12. Protects Against Peptic Ulcers

It is well known that various plant-originated “gastroprotectors” with different compositions have been used in clinical and folk medicine due to their beneficial effects on the mucosa of gastrointestinal tract. Ethanolic and ethyl-acetate leaf extracts of A. tricolor showed gastric-ulcer healing effect in acetic acid-induced chronic gastric ulcers and gastric cytoprotective effect in ethanol and indomethacin-induced gastric ulcers in pylorus-ligated rats [30]. A combined use of this extract with two other herbs will help to improve the antiulcer properties [31].

It has been found that duodenal peptic ulcer and chronic gastritis caused by Helicobacter pylori can be treated with amaranth oil [32].

13. Snack Bonus:

Amaranth flowers are versatile leafy vegetables that you can even turn into a delicious snack with a nutty flavor! You can pop amaranth, like popcorn, and use it as a healthy snack or as a treat by mixing it with coconut syrup or honey.

If you want you can also use it to make gluten-free baked goods or amaranth chips. Follow your favorite baking recipes but replace wheat flour with amaranth. In doing so you get that snacking fix but in the format of a superfood (rather than a junkfood).

14. Improves Bone Health:

Manganese is one important mineral this vegetable contains, which plays a role in bone health. One cup of amaranth offers 105% of the daily value of manganese, making it one of the richest sources of the mineral.

According to the International Osteoporosis Foundation, amaranth is one of the ancient grains important for a bone-healthy diet. It contains protein, calcium, and iron – nutrients crucial for bone health . It also happens to be the only grain to contain vitamin C, which helps improve the health of ligaments and also fights inflammation (and associated inflammatory ailments like gouts and arthritis).

And being rich in calcium, amaranth helps heal broken bones and even strengthens the bones. One 2013 study stated that consuming amaranth was an effective way to meet our daily needs of calcium and other bone-healthy minerals like zinc and iron.

These characteristics of amaranth also make it a good treatment for osteoarthritis.

15. Improves Vision:

Amaranth contains vitamin A, which is known to improve vision. The vitamin is important for vision under poor lighting conditions, and it also prevents night blindness (caused by vitamin A deficiency).

The vitamin A found in amaranth also has a major effect on the health of our ocular system. Beta-carotene is an antioxidant that prevents the development of cataracts and can slow the onset of macular degeneration.

Amaranth as a hepatoprotective:

A study carried out by Zeashan et al. [51] showed the hepatoprotective and antioxidant activity of 50% ethanolic extract of a whole plant of Amaranthus spinosus using carbon tetrachloride-induced hepatic damage in rats. Furthermore, this study suggests that possible mechanism of this activity may be due to the presence of flavonoid and phenolic compound in the A. spinosus which may be responsible to hepatoprotective activity [51].

Additional study was carried out using the ethanolic extract of Amaranthus tricolor L. leaves, to test its efficacy against CCl4-induced liver toxicity in rats. The results indicate that A. tricolor extract significantly increases the activities of nonprotein sulfhydryl (NP-SH) and total protein (TP) in liver tissue supporting the evaluation of the liver histopathology in rats [52].

Amaranth: Both the greens and seeds are edible, with the greens tasting somewhat like spinach, and the seeds milled into flour or eaten much like quinoa with a similar protein punch.

Amaranth has antimicrobial activity

An antimicrobial is a natural or synthetic agent that kills microorganisms or slows the spread of microorganisms such as bacteria, fungi, and algae. Amaranthus sp. antimicrobial properties have been studied and exploited by mankind for several decades. The roots, leaves, and seeds of Amaranthus spp. have been used in the evaluation of its antimicrobial activities against Gram-positive and Gram-negative bacteria, such as Bacillus subtilis, B. bronchiseptica, Bacillus cereus, B. pumilus, Micrococcus flavus, S. aureus, Sarcina lutea, E. coli, and P. vulgaris, among others [48, 49]. For the last 10 years, our research group has been working in antimicrobial peptides due to great interest to overcome the growing problem of antimicrobial resistance. An antifungal peptide called Ay-AMP was isolated from Amaranthus hypochondriacus seeds by acidic extraction and then purified by reverse-phase high-pressure liquid chromatography.

Amaranth as an antimalarial

Malaria is an infectious disease caused by protozoan parasites from the Plasmodium family that can be transmitted by the bite of the Anopheles mosquito or by a contaminated needle or transfusion. In this context, falciparum malaria is the most deadly type. The symptoms of malaria include cycles of chills, fever, sweats, muscle aches, and headache that recur every few days. There can also be vomiting, diarrhea, coughing, and yellowing (jaundice) of the skin and eyes. Persons with severe falciparum malaria can develop bleeding problems, shock, kidney and liver failure, central nervous system problems, coma, and death. Travelers to areas with malaria are advised to take medications to prevent infection if exposed.

Extracts obtained from two Burkinabe folk medicine plants, both spiny amaranth (Amaranthus spinosus L., Amaranthaceae) and erect spiderling (Boerhavia erecta L., Nyctaginaceae) were screened for antimalarial properties with the aim of testing the validity of their traditional uses. The plant extracts showed significant antimalarial activities in the 4-day suppressive antimalarial assay in mice inoculated with red blood cells parasitized with Plasmodium berghei.

A combination of two plant extracts of Launaea taraxacifolia and Amaranthus viridis is used by people of Western Africa in the treatment of malaria and related symptoms. This study assessed for their antiplasmodial value against the chloroquine-sensitive strain of Plasmodium berghei. This study showed that the methanolic extracts of A. viridis and L. taraxacifolia possess antiplasmodial activity.

Amaranth has an antianemic effect

Anemia is defined as a low level of hemoglobin in red blood cells. The major clinical symptom of anemia and iron deficiency shows a pale color of the skin, and its physical symptom is fatigue. According to the UNICEF, anemia has an impact on the intellectual development of children; it reduces learning ability and growth and damages the immune system.

Mexico is an underdeveloped country with malnutrition conditions. In our country, anemia is a public health problem generalized in all social socioeconomic status. Amaranthus has been rediscovered as a promising food crop mainly due to its resistance to heat, drought, diseases and pests, and the high nutritional value of both seeds and leaves. They are rich in proteins and micronutrients such as iron, calcium, zinc, vitamin C, and vitamin A (shown in the Tables in the article above).

Hair Care

The unique chemical makeup up amaranth grain has some rather unexpected benefits as well, including being a wonderful way to flatten wiry hair and increase luster and quality. Dr. Norlin J Benevenga, Department of Animal Sciences, University of Wisconsin, USA, in his report published in the Journal of Nutrition states that lysine is a critical amino acid that our body is unable to produce, so we must get it from our diet. Amaranth has higher levels of lysine than other grains, which makes it very important for hair health. Lysine has been linked to stronger and healthier hair, better roots, and a reduction in hair loss. You can reduce greying and hair loss by adding amaranth grains to your diet.

Harvesting and Saving Seed from Amaranth:

Greens are best harvested when young and tender and can be added to salads or stir fries. Larger leaves are tougher but can make a nice addition to soup broths for an extra nutritional boost. Harvesting the amaranth seed (sometimes referred to as an “ancient grain”) is done once the flowers have matured. Seeds ripen about three months after planting, usually in the mid- to late summer, depending on your climate and when you planted. They are ready to harvest when they begin to fall from the flower head (tassel). Give the tassel a gentle shake. If you see seeds falling from the tassel, it’s amaranth seed harvest time.

I have used several methods for harvesting amaranth seed and have found the fastest way to get the seed under ideal conditions is to wait until the seeds are ripe and the flower heads are dry (can fall out of the flower head when you shake it) and use a wheel barrow with a replacement screen for a patio door or window placed over the wheel barrow to help separate the chaff from the seeds.

I shake and rub the mature flower heads over the screen and the seeds (being tiny) fall through the screen while most of the debris is kept out.

Here is a short video that showed our early experiments with this method:

This method does not get every last seed but it helps save time if you have the good weather (and access to the tools required). I use this method when i can because it is good for processing a moderate amount of homegrown amaranth seed in a hurry.

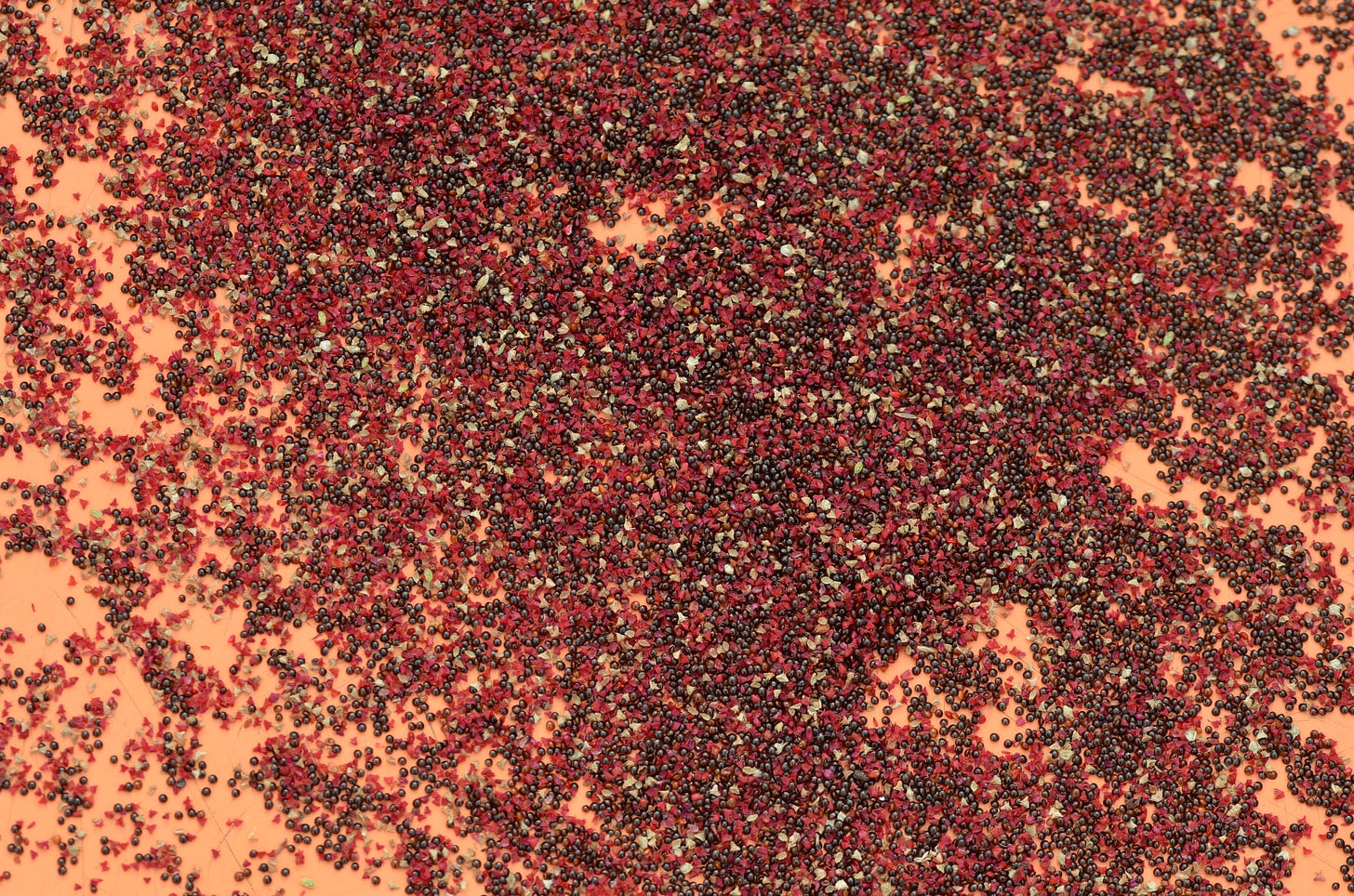

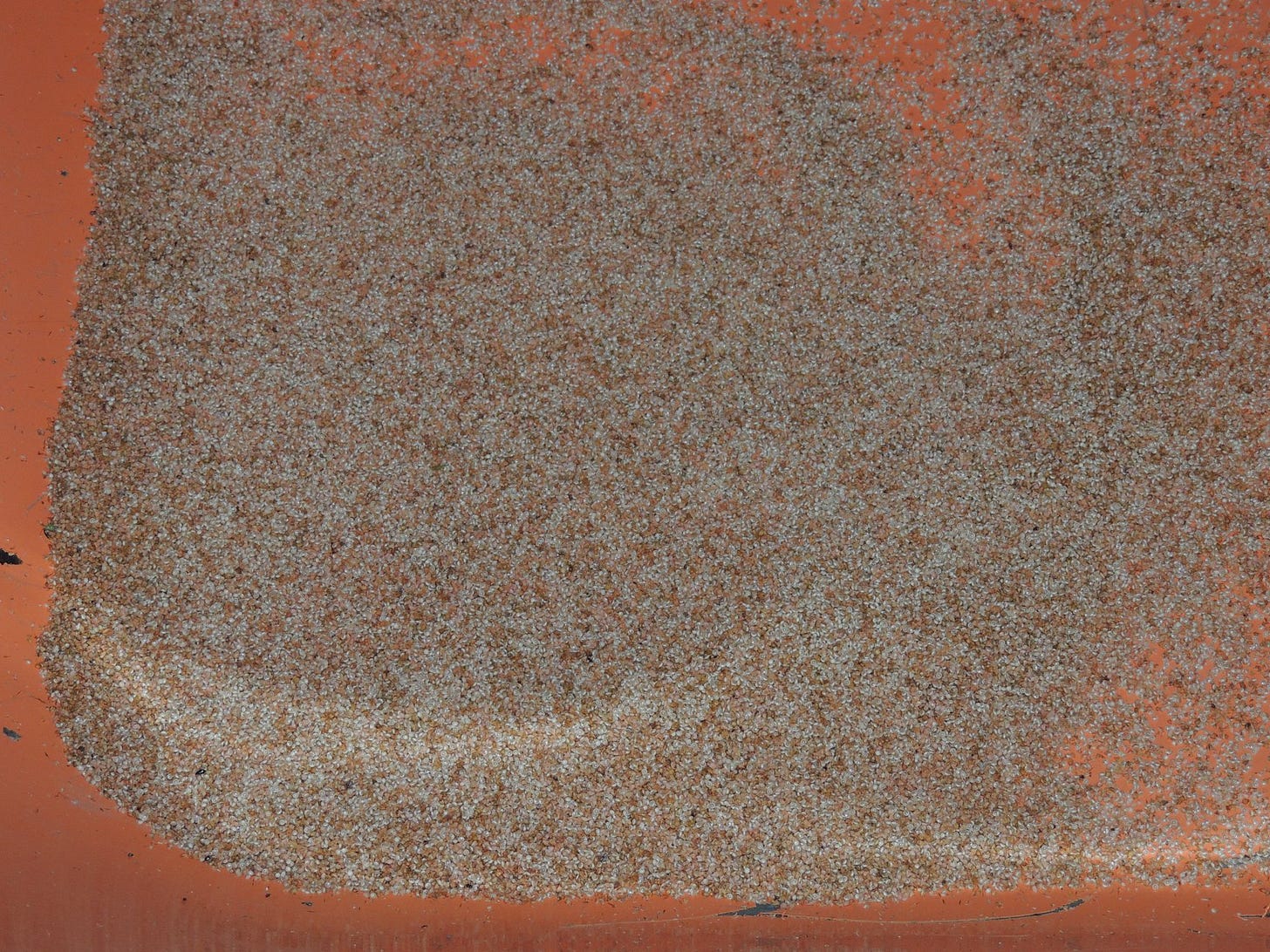

Here are a few pics of how our 2022 harvest of Hopi Red Dye Amaranth seeds went (using the same method described above):

After you have the seeds (and the little bit of chaff/debris that made it through the screen) in the wheel barrow, you can then pour this into a tote or other container to bring inside.

Once you have it inside (or at least in an area protected from the elements) you will want to spread the seeds in a thin layer in a cool, dark, dry place to further dry. After the seeds and remaining flower debris dry a bit more you can separate the final little bits of chaff/debris from the seeds before storing for cooking with later (or saving seed for sowing next years crop).

Once the seeds are fully dry (after sitting for about 1-2 weeks in the cool, dry, dark place thinly spread out on a flat surface) you can separate the final bits of chaff and debris from the seeds by using a pie dish to move around the seeds and debris in a circular motion while lightly blowing on the contents of the dish. The air movement sends the lighter chaff flying out of the dish (leaving the majority of the larger seeds in the dish). Do this in small batches until you have removed the desired amount of chaff and they are ready to cook with, store for cooking with later (in an airtight container) or save for sowing next years crop.

If you do not have a wheel barrow nor an old or new replacement window/door screen (and/or the weather is not cooperating to give you dry mature flower heads) you can use the alternative method of harvesting the mature flower heads and hanging them up inside (or under cover) over a tarp (to catch any seeds that fall out). Once they are dry and brittle you can then rub the flower heads to break up the seeds and chaff and run them through a strainer/sieve to separate the bigger chaff/stem pieces from the seeds and smaller particles. Be aware that dry mature amaranth flower heads can be rough on the skin. So if you are processing quite a bit, using gloves may be advisable to prevent your skin getting banged up. After the first step in this method you will want to shake around your seeds and smaller particles/chaff in a large container to get the seeds to settle in the bottom and then scoop off the larger debris from the top. After you have removed as much of the larger pieces as possible you can then do the same thing that was described using the pie dish and blowing to separate the finer chaff from the seeds before storing. You can also use a fan on the light setting or utilize a light breeze outside to do the final separation of light small chaff from seeds, though I prefer the control that blowing on the pie dish provides for the scale I am harvesting amaranth at.

Recipe Ideas For Enjoying Your Amaranth Harvest In The Kitchen

As mentioned above Amarnath seeds can be popped (or “puffed”) in a similar fashion to how corn kernels can be popped to almost instantly open up the bioavailability of the nutrients locked up in the raw seeds in a fun snackable and bake-able format.

After you harvest your Amaranth seeds in the fall you can also sprout them (at any time of year) to produce fresh sprouts, microgreens and/or baby greens for salads, smoothies or sandwich greens on demand.

Amaranth microgreens are one of the lesser known microgreens but they are one that is really worth growing. They are a delicious addition to salads and as garnishes on a variety of dishes. Plus, they are soooo good for you and packed with antioxidants due to their unique color! Here is some info on how to grow amaranth microgreens.

As Amaranth leaves mature in the garden you can harvest them for cooking as well. They are delicious in salads when they are young and tender and then they go great in soups and sautéed along side other veggies or if you are using the mature rigid leaves, they are great for enriching veggie broths.

The seeds can also be boiled and used in the place of rice or quinoa for stuffing peppers, making pilafs, making cabbage rolls or making salads.

In addition to being a great substitute for grains and rice in dishes I have also successfully added cooked amaranth seed to batches of homemade miso paste. Fermenting legumes and ancient grains (like Amaranth) with Koji mold (Aspergillus oryzae) and L.A.B. is a process that requires patience and faith but offers rich potential for creative expression and extending the shelf life, flavor, health benefits and bioavailability of some of your favorite garden crops. I basically followed the recipe as far as the ratio of legumes to salt to koji from "The Art Of Fermentation" but I included non-traditional legumes and grains along side the traditionally used soybeans.

I hope your enjoyed this article about the amazing and versatile Amaranth and will try growing some in your own garden next year.

I will have more fun recipes that can include Amaranth seed and leaves in my upcoming book.

References for those interested in doing more in depth research on Amaranth:

Rastogi A, Shukla S. Amaranth: A new millenium crop of nutraceutical values. Critical Reviews in Food Science and Nutrition. 2013;53(2):109-125. DOI: 10.1080/10408398.2010.517876

Espitia-Rangel E. Breeding of grain amaranth. In: Paredes-Lopez O, editor. Amaranth. Biology, Chemistry and Technology. Boca Raton, USA: CRC Press; 1994. pp. 23-38

National Academy Press. Amaranth: Modern Prospects for an Ancient Crop. Washington, DC: National Academic of Sciences; 1984

Ulbricht C, Abrams T, Conquer J, Costa D, Grims-Serrano JM, Taylor S, et al. An evidence-based systematic review of amaranth (Amaranthus spp.) by the natural standard Research collaboration. Journal of Dietary Supplements. 2009;6(4):390-417. DOI: 10.3109/19390210903280348

Venskutonis PR, Kraujalis P. Nutritional components of amaranth seeds and vegetables: A review on composition, properties, and uses. Comprehensive Reviews in Food Science and Food Safety. 2013;12(4):381-412. DOI: 10.1111/1541-4337.12021

Jahaniaval F, Kakuda Y, Marcone MF. Fatty acid and triacylglycerol compositions of seed oils of five Amaranthus accessions and their comparison to other oils. Journal of the American Oil Chemists' Society. 2000;77(8):847-852. DOI: 10.1007/s11746-000-0135-0

USDA. Subset, Food, and All Foods. National Nutrient Database for Standard Reference, Amaranth grain. Release 28; 2016

Kalinova J, Dadakova E. Rutin and total quercetin content in amaranth (Amaranthus spp.). Plant Foods for Human Nutrition. 2009;64(1):68-74. DOI: 10.1007/s11130-008-0104-x

Barba de la Rosa AP et al. Amaranth (Amaranthus hypochondriacus) as an alternative crop for sustainable food production: Phenolic acids and flavonoids with potential impact on its nutraceutical quality. Journal of Cereal Science. 2009;49:117-121. DOI: 10.1016/j.jcs.2008.07.012

Gorinstein S et al. Comparison of composition and antioxidant capacity of some cereals and pseudocereals. International Journal of Food Science and Technology. 2008;43(4):629-637. DOI: 10.1111/j.1365-2621.2007.01498.x

Klimczak I, Małecka M, Pachołek B. Antioxidant activity of ethanolic extracts of amaranth seeds. Food/Nahrung. 2002;46(3):184-186. DOI: 10.1002/1521-3803(20020501)46:3<184::AID-FOOD184>3.0.CO;2-H

López VRL, Razzeto GS, Giménez MS, Escudero NL. Antioxidant properties of Amaranthus hypochondriacus seeds and their effect on the liver of alcohol-treated rats. Plant Foods for Human Nutrition. 2011;66(2):157-162. DOI: 10.1007/s11130-011-0218-4

Bejosano FP, Corke H. Protein quality evaluation of Amaranthus whole meal flours and protein concentrates. Journal of the Science of Food and Agriculture. 1998;76:100-106. DOI: 10.1002/(SICI)1097-0010(199801)76:1<100::AID-JSFA931>3.0.CO;2-B

Pisarikova B, Kracmar S, Herzig I. Amino acid contents and biological value protein in various amaranth species. Czech Journal of Animal Science. 2005;50(4):169-174. DOI: 10.1002/(SICI)1097-0010(199801)76:1<100::AID-JSFA931>3.0.CO;2-B

Shukla S et al. Nutritional contents of different foliage cuttings of vegetable amaranth. Plant Food for Human Nutrition. 2003;58(3):1-8. DOI: 10.1023/B:QUAL.0000040338.33755.b5

Kraujalis P, Venskutonis PR. Optimization of supercritical carbon dioxide extraction of amaranth seeds by response surface methodology and characterization of extracts isolated from different plant cultivars. Journal of Supercritical Fluids. 2013;73:80-86. DOI: 10.1016/j.supflu.2012.11.009

Caselato–Sousa VM, Amaya–Farfán J. State of knowledge on Amaranth grain: A comprehensive review. Journal of Food Science. 2012;77(4):R93-R104. DOI: 10.1111/j.1750-3841.2012.02645.x

Stone LA, Lorenz K. The starch of Amaranthus: Physiochemical properties and functional characteristics. Starch. 1984;36(7):232-237. DOI: 10.1002/star.19840360704

Oleszek W, Junkuszew M, Stochmal A. Determination and toxicity of saponins from Amaranthus cruentus seeds. Journal of Agricultural and Food Chemistry. 1999;47(9):3685-3687. DOI: 10.1021/jf990182k

Vasco Méndez NL, Soriano-García M, Moreno A, et al. Purification, crystallization and preliminary X–ray characterization of a 36kDa Amaranth globulin. Journal of Agricultural and Food Chemistry. 1999;47(3):862-866. DOI: 10.1021/jf9809131

Negro M, Giardina S, Marzani B, Marzatico F. Branched-chain amino acid supplementation does not enhance athletic performance but affects muscle recovery and the immune system. The Journal of Sports Medicine and Physical Fitness. 2008;48(3):347-351

Montoya-Rodríguez A, de Mejía EG, Dia VP, et al. Extrusion improved the anti-inflammatory effect of amaranth (Amaranthus hypochondriacus) hydrolysates in LPS-induced human THP-1 macrophage-like and mouse RAW 264.7 macrophages by preventing activation of NF-κB signaling. Molecular Nutrition & Food Research. 2014;58(5):1028-1041. DOI: 10.1002/mnfr.201300764

Laparra JM, Haros M. Inclusion of ancient Latin–American crops in bread formulation improves intestinal iron absorption and modulates inflammatory markers. Food & Function. 2016;7(2):1096-1102. DOI: 10.1039/c5fo01197c

Macdonald HM, New SA, Golden MH, et al. Nutritional associations with bone loss during the menopausal transition: Evidence of a beneficial effect of calcium, alcohol, and fruit and vegetable nutrients and of a detrimental effect of fatty acids. The American Journal of Clinical Nutrition. 2004;79(1):155-165. DOI: 10.1093/ajcn/79.1.155

Levis S, Lagari VS. The role of diet in osteoporosis prevention and management. Current Osteoporosis Reports. 2012;10(4):296-302. DOI: 10.1007/s11914-012-0119-y

Sacco SM, Horcajada MN, Offord E. Phytonutrients for bone health during ageing. British Journal of Clinical Pharmacology. 2013;75(3):697-707. DOI: 10.1111/bcp.12033

Galan MG, Drago SR, Armada M, José RG. Iron, zinc and calcium dialyzability from extruded product based on whole grain amaranth (Amaranthus caudatus and Amaranthus cruentus) and amaranth/Zea mays blends. International Journal of Food Sciences and Nutrition. 2013;64(4):502-507. DOI: 10.3109/09637486.2012.753038

A B et al. Cholesterol-lowering properties of amaranth grain and oil in hamsters. International Journal for Vitamin and Nutrition Research. 2003;73(1):39-47. DOI: 10.1024/0300-9831.73.1.39

Mendonça S, Saldiva PH, Cruz RJ, Arêas JAG. Amaranth protein presents cholesterol-lowering effect. Food Chemistry. 2009;116:738-742. DOI: 10.1016/j.foodchem.2009.03.021

Devaraj VC, Krishna BG. Gastric antisecretory and cytoprotective effects of leaf extracts of Amaranthus tricolor Linn in rats. Zhong Xi Yi Jie He Xue Bao. 2011;9:1031-1038. DOI: 10.3736/jcim20110915

Devaraj VC, Krishna BG. Antiulcer activity of a polyherbal formulation (PHF) from Indian medicinal plants. Chinese Journal of Natural Medicines. 2013;11(2):145-148. DOI: 10.1016/S1875-5364(13)60041-2

Cherkas A et al. Amaranth oil reduces accumulation of 4-hydroxynonenal-histidine adducts in gastric mucosa and improves heart rate variability in duodenal peptic ulcer patients undergoing Helicobacter pylori eradication. Free Radical Research. 2018;52(2):135-149. DOI: 10.1080/10715762.2017.1418981

Kim HK, Kim MJ, Yon H, et al. Antioxidative and anti-diabetic effects of amaranth (Amaranthus esculantus) in streptozotocin-induced diabetic rats. Cell Biochemistry and Function. 2006;24(3):195-199. DOI: 10.1002/cbf.1210

Aschner JL, Aschner M. Nutritional aspects of manganese homeostasis. Molecular Aspects of Medicine. 2005;26(4-5):353-362. DOI: 10.1016/j.mam.2005.07.003

Rucker D, Thadhani R, Tonelli M. Trace element status in hemodialysis patients. Seminars in Dialysis. 2010;23(4):389-395. DOI: 10.1111/j.1525-139X.2010.00746.x

Koh ES, Kim SJ, Yoon HE, et al. Association of blood manganese level with diabetes and renal dysfunction: A cross–sectional study of the Korean general population. BMC Endocrine Disorders. 2014;14:24-32. DOI: 10.1186/1472-6823-14-24

Lee SH, Jouihan HA, Cooksey RC, et al. Manganese supplementation protects against diet–induced diabetes in wild type mice by enhancing insulin secretion. Endocrinology. 2013;154(3):1029-1038. DOI: 10.1210/en.2012-1445

Miroshnichenko LA, Zoloedov VI, Volynkina AP, et al. Influence dietary therapy with use sunflower and amaranth oils on parameters of immune reactivity in patients with diabetes mellitus 2 type. Voprosy Pitaniia. 2009;78(4):30-36

Yelisyeyeva O, Semen K, Zarkovic N, et al. Activation of aerobic metabolism by Amaranth oil improves heart rate variability both in athletes and patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus. Archives of Physiology and Biochemistry. 2012;118(2):47-57. DOI: 10.3109/13813455.2012.659259

Rahaie S, Gharibzahedi SM, Razavi SH, et al. Recent developments on new formulations based on nutrient–dense ingredients for the production of healthy–functional bread: A review. Journal of Food Science and Technology. 2014;51(11):2896-2906. DOI: 10.1007/s13197-012-0833-6

Inglett G, Chen D, Liu S. Physical properties of gluten-free sugar cookies made from amaranth–oat composites. LWT--Food Science and Technology. 2015;63(1):214-220. DOI: 10.1016/j.lwt.2015.03.056

Mansueto P, Seidita A, D’Alcamo A, et al. Non–celiac gluten sensitivity: Literature review. Journal of the American College of Nutrition. 2014;33(1):39-54. DOI: 10.1080/07315724.2014.869996

Butterworth CE Jr, Tamura T. Folic acid safety and toxicity: A brief review. The American Journal of Clinical Nutrition. 1989;50:353-358. DOI: 10.1093/ajcn/50.2.353

Feinleib M et al. Folate fortification for the prevention of birth defects: Case study. American Journal of Epidemiology. 2001;154(12):S60-S69

King DE, Mainous AG III, Lambourne CA. Trends in dietary fiber intake in the United States, 1999-2008. Journal of the Academy of Nutrition and Dietetics. 2012;112(5):642-648. DOI: 10.1016/j.jand.2012.01.019

WHO (World Health Organization). Global Strategy On Diet, Physical Activity and Health. Geneva A57/9: WHO; 2004

Peter K, Gandhi P. Rediscovering the therapeutic potential of Amaranthus species: A review. Egyptian Journal of Basic and Applied Sciences. 2017;4:196-205. DOI: 10.1016/j.ejbas.2017.05.001

Maiyo ZC, Ngure RM, Matasyoh JC, Chepkorir R. Phytochemical constituents and antimicrobial activity of leaf extracts of three Amaranthus plant species. African Journal of Biotechnology. 2010;9:3178-3182

Sheeba AM, Deepthi SR, Mini I. Evaluation of antimicrobial potential of an invasive weed Amaranthus spinosus L. In: Sabu A, Augustine A, editors. Prospects in Bioscience: Addressing the Issues. India: Springer; 2012:117-123

Rivillas-Acevedo LA, Soriano-García M. Isolation and biochemical characterization of an antifungal peptide from Amaranthus hypochondriacus seeds. Journal of Agricultural and Food Chemistry. 2007;55(25):10156-10161. DOI: 10.1021/jf072069x

Zeashan H, Amresh G, Singh S, Rao CV. Hepatoprotective and antioxidant activity of Amaranthus spinosus against CCl4 induced toxicity. Journal of Ethnopharmacology. 2009;125(2):364-366. DOI: 10.1016/j.jep.2009.05.010

Al-Dosari MS. The effectiveness of ethanolic extract of Amaranthus tricolor L.: A natural hepatoprotective agent. The American Journal of Chinese Medicine. 2010;38(6):1051-1064. DOI: 10.1142/S0192415X10008469

Gandhi P, Khan Z, Niraj K. In vitro assay of anti-proliferative potential of Amaranthus cruentus aqueous extract on human peripheral blood lymphocytes. Current Trends in Biotechnology and Chemical Research. 2011;1:42-48. DOI: 10.1142/S0192415X10008469

Baskar AA, Al Numair KS, Alsaif MA, Ignacimuthu S. In vitro antioxidant and antiproliferative potential of medicinal plants used in traditional Indian medicine to treat cancer. Redox Report. 2012;17:145-156. DOI: 10.1179/1351000212Y.0000000017

Shiel WC Jr. Medical definition of malaria. Medicine Net. Visited April 30, 2019. Available from: https://www.medicinenet.com/script/main/art.asp?articlekey=4255

Hiloua A, Nacoulmaa OGT, Guiguemdeb R. In vivo antimalarial activities of extracts from Amaranthus spinosus L. and Boerhaavia erecta L. in mice. Journal of Ethnopharmacology. 2006;103(2):236-240. DOI: 10.1016/j.jep.2005.08.006

Adetutu A, Olorunnisola OS, Owoade AO, Adegbola P. Inhibition of in vivo growth of Plasmodium berghei by Launaea taraxacifolia and Amaranthus viridis in Mice. Malaria Research and Treatment. 2016;2016:9. DOI: 10.1155/2016/9248024

Ramírez-Medeles MC, Aguilar MB, Miguel RN, Bolaños-García VM, García-Hernández E, Soriano-García M. Amino acid sequence, biochemical characterization and comparative modeling of a non-specific lipid transfer protein from Amaranthus hypochondriacus. Archives of Biochemistry and Biophysics. 2003;415(1):24-33. DOI: 10.1016/S0003-9861(03)00201-7

Mendoza-Figueroa JS, Kvarnheden A, Méndez-Lozano J, Rodríguez-Negrete EA, Arreguín-Espinosa de los Monteros R, Soriano-García M. A peptide derived from enzymatic digestion of globulins from amaranth shows strong affinity binding to the replication origin of Tomato yellow leaf curl virus reducing viral replication in Nicotiana benthamiana. Pesticide Biochemistry and Physiology. 2018;45:56-65. DOI: 10.1016/j.pestbp.2018.01.005

Silva-Sánchez C et al. Bioactive peptides in amaranth (Amaranthus hypochondriacus) seed. Journal of Agricultural and Food Chemistry. 2008;56(4):1233-1240. DOI: 10.1021/jf072911z

Sabbione AC, Scilingo A, Añón MC. Potential antithrombotic activity detected in amaranth proteins and its hydrolyzates. LWT-Food Science and Technology. 2015;60(1):171-177. DOI:10.1016/j.lwt.2014.07.015

Quiroga A, Barrio D, Añón MC. Amaranth lectin presents potential antitumor properties. LWT- Food Science and Technology. 2015;60(1):478-485. DOI: 10.1016/j.lwt.2014.07.035

Fuentes Reyes M, Chávez-Servín JL, González-Coria C, et al. Comparative account of phenolics, antioxidant capacity, α-tocopherol and anti-nutritional factors of amaranth (Amaranthus hypochondriacus) grown in the greenhouse and open field. International Journal of Agriculture and Biology. 2018;20(11):2428-2436. DOI: 10.17957/IJAB/15.0786

Holy Moly! What a comprehensive article on Amaranth! I wish I had seen it a few months ago but I will make a note to re-read it next year. I moved to the country in 2020 (New Hampshire/USA) and my gardening attempts have been far from stellar. I blame it on the vicious black flies and deer flies that loved my garden spot near the woods a little too much. I got ravaged just trying to water. Anyway, this year Amaranth appeared and took over the entire 25'x25' area. I ate the leaves but am sad to report that I didn't harvest any of the seeds. The birds and my lil chipmunk friend had a field day. Next year, I imagine she will be back in full force from all of the seeds that fell. And now, I will have this article to refer to! Thank you, Gavin!

wow. well researched referenced and delicious looking xxx