Day Eight: STAGHORN SUMAC

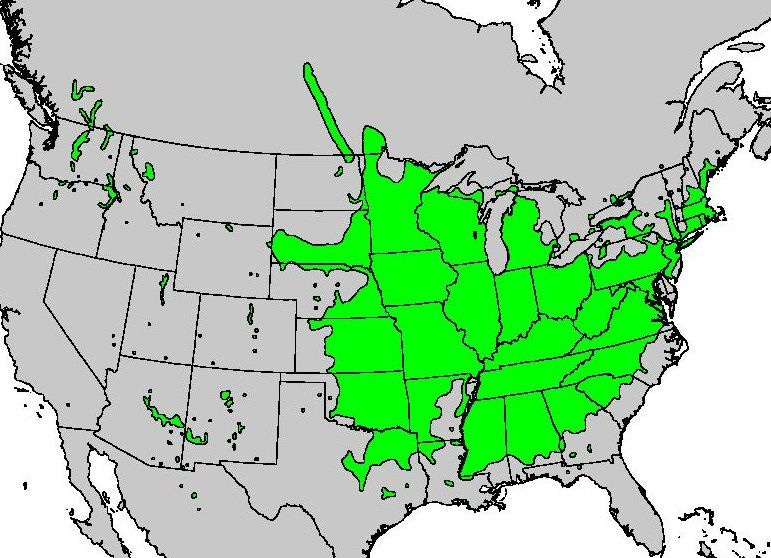

It grows all over Canada and the US offering nutritious berries, soil stabilization, habitat for birds and vibrantly flavored seasoning for creating in the kitchen

Staghorn Sumac is an absolute blessing to humanity and all life and has a wide range of uses from craft to beekeeping, from herbal to edible. The berries are high in Vitamin C and have incredible amounts of antioxidants, making them a wonderful healthful food.

Modern studies find the compounds in sumac berries offer antibiotic, anti-cancer, anti-oxidant and other benefits.

If you have not had sumac, you will be delighted to discover its tart, lemony flavour. Staghorn sumac has been present everywhere I have lived in Canada, and looks like a giant raspberry turned upside down with lot of little berries/fruits. The red upright cones, are ready for harvest from the end of July into early fall. If you touch the inside of the flowers and your finger is a bit tacky to touch (or tastes tangy), then it is ready to be picked.

History and cultural significance of Staghorn Sumac:

Sumac species are treasured around the globe and the berries of various species have many uses in Native American and First Nation tribes including as a refreshing lemonade style beverage. Sumac is known as baakwaanaatig by the Ojibwe.

Rhus coriaria (Sicilian sumac) berries are used to make a very popular spice in the Middle East where the term "Rhus" or red in Arabic is derived.

Staghorn sumac is known as Sumac des corroyeurs in French, Sommacco in Italian, Oţetarin Romanian, Աղտոր Սովորական in Armenian and Zumaque in Spanish.

Believed by some Native American tribes to foretell the weather and the changing of the seasons, for this reason (and many others) it was held as a sacred plant.

Sumac was used by Native American peoples for a variety of sacred purposes. For example, in “Dancing Gods: Indian Ceremonials of New Mexico and Arizona” by Erna Fergusson (1931), the nahikàï is a wand used as part of a Navajo shamanistic healing ceremony. It is sumac, made about 3 feet long and about ½” thick. Eagle down is attached to the end of the wand, and it is burned off as part of the ceremony. In the Hopi “Legend of Palotquopi” a young boy, Kochoilaftiyo, asks his grandmother what to do about a ghost that is coming to the village. Young men in the village have been attempting to catch the ghost to no avail. Grandmother has him go get a sumac branch, and with this branch and prayer plumes made of cotton and feathers, she creates a pipe and smokes a prayer over him that he might prevail. In The Religion of the Luiseño Indians of Southern California, by Constance Goddard DuBois, (1908), describes an initiation ceremony where young girls are initiated as women into the tribe. As part of this ceremony, a young girl is placed in a sumac and sedge-lined hole, where she says for three days, while members of her tribe dance and sing night and day around the hole. This practice is part of a larger ceremony of womanhood.

In a bear legend, from the Apache, called “Turkey makes the corn and Coyote plants it” a brother and a sister are hungry. Turkey overhears this and shakes his feathers and fruits and food come out. Bear comes and brings juniper nuts, various kinds of nuts, and sumac.

The berries of the staghorn and smooth sumac have been eaten by the indigenous peoples of what is now called Canada and the United States for well over one thousand years.

The berries were often used to make a beverage, which the Cherokee called quallah. Sumac berries were put under warm-hot water to create a tasty lemony drink. Quallah was and is still used today to mark many ceremonies and traditions.

Native American use varied by tribe. The Abenaki mixed its leaves and berries with tobacco for smoking. The Menominee used its liquid at both ends: as a gargle for coughs and as a relief from hemorrhoids. The milky white juice from a cut twig served them as an astringent. The Cherokee and Delaware applied sumac for any number of problems that required strong medicine. Ute basket weavers preferred the supple twigs of fragrant sumac for ceremonial baskets, while willow branches could be used to weave coarser working baskets.

A surprising range of pigments were extracted from sumac for dyeing baskets and blankets. Navajo used fermented berries to create an orange-brown dye, while a different extraction from berries produced red. Crushed twigs and leaves yielded a black dye when mixed with ochre mineral and the resin of pinyon pine. Roots produced a yellow dye and a light-yellow dye could be made from the pulverized pulp of stems. Tannins extracted from leaves produce a brown dye.

Sumacs in their ubiquity have been described, catalogued and commented on since olden times. Naturalist Pliny the Elder, writing in the first century, noted the use of the juice of the fruit of the “sumach-tree of Syria” by curriers in the making of leather. Pliny compared the appearance of the seed to that of a lentil and wrote that it “forms a necessary ingredient in various medicaments.” The ancients mistakenly believed it to be a relief for fever, but they were accurate about its ability to help preserve animal skins. The Japanese, in their famous and oft-imitated black lacquers, were said to use its sap. In China, the Chinese characters for sumac literally mean “paint tree.” An 11th-century shipwreck, discovered centuries later off the coast of Rhodes, Greece, was filled with containers of sumac drupes that were being shipped to market.

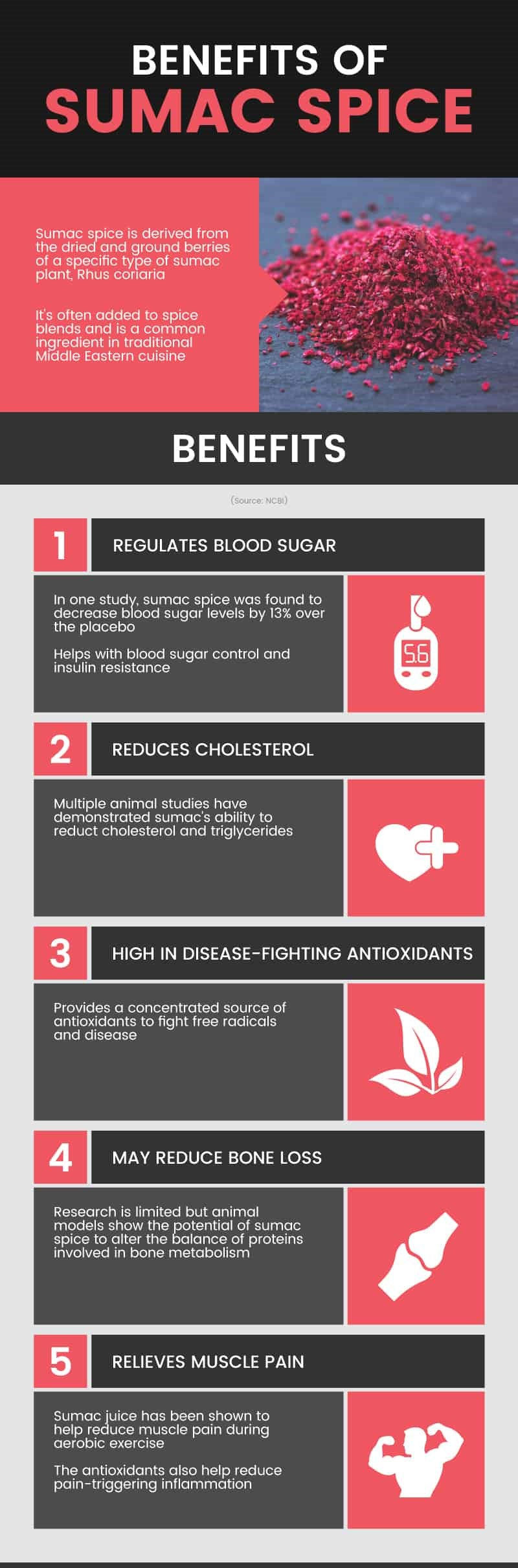

Sumac berries are also useful dried for seasoning; if you have smooth (rhus glabra) or shining sumac (rhus copallinum) some they may be preferable for this (But I have found you can use staghorn sumac berries with good results as well) You have to sift out the seeds from the ground berries and discard the seeds. You’re left with a red, velvety fuzz – a lemony spice (more on this later). You can use sumac spice for cooking, perhaps as a rub for roasts, baking hearty veggies, in stir fries, on eggs and in curries. It’s also a treat sprinkled on hummus. In middle eastern cooking, the berries of a sumac variety (that is similar to Staghorn) from their neck of the woods (called Rhus Coriaria) are dried and used as a prime ingredient in the spice mix za’atar and for seasoning a delicious salad called fattoush (I share ideas for several variations of this below).

Sumac in Medicine:

The Ojibwe use the different varieties of sumac for various purposes. The inner bark of the plant can be made into a substance for external application as an astringent, protecting the skin and relieving minor skin irritations. The Ojibwe traditionally used outer bark as a hemostatic to stop the blood gushing from open wounds. In addition to the bark, the blossoms of the smooth sumac plant can also treat several issues. As a baby teethes, the blossom can ease the ache of their mouths. If mixed into a rinse, these blossoms can also alleviate sore eyes. Finally, the Ojibwe also used smooth sumac in a decoction to treat dysentery (Densmore 2005, 344).

Other Uses:

Sumac, with about 250 species across the world, has been used throughout history for everything from medicines to a dinner garnish, an ingredient in wax, a tobacco additive and a dye. Various members of the sumac family (Anacardiaceae) can be found in North America, southern Africa, eastern Asia and northeastern Australia in a variety of forms, including deciduous or evergreen, shrubs, trees or woody climbers, in temperate or subtropical climates. In North America, sumacs are common in roadside ditches, known for their brilliant red or orange leaves in the fall.

Parts of smooth sumac have been used by various Native American tribes as an antiemetic, antidiarrheal, antihemorrhagic, blister treatment, cold remedy, emetic, mouthwash, asthma treatment, tuberculosis remedy, sore throat treatment, ear medicine, eye medicine, astringent, heart medicine, venereal aid, ulcer treatment, and to treat rashes. Staghorn sumac parts were used in similar medicinal remedies. The Natchez used the root of fragrant sumac to treat boils. The Ojibwa took a decoction of fragrant sumac root to stop diarrhea. The berries, roots, inner bark, and leaves of smooth and staghorn sumac were used to make dyes of various colors. The leaves of fragrant, staghorn and smooth sumac were mixed with tobacco and smoked by many tribes of the plains region (Moerman 1998: 471-473).

Healing and Nutritional Benefits

“Sumac-ade” is purely, simply, and tartly delicious. The ancient First Nation peoples who crafted and enjoyed the beverage knew quite well too, there was much more to the cooling berry than that.

• High in vitamin C, and antiviral compounds good for immunity

• Contains antioxidants for cellular protection

• Contains gallic acids, potent antimicrobial compounds

• Demonstrated blood sugar-regulating activity, good for diabetics

• Lowers bad cholesterol, while boosting good cholesterol

• Prevents atherosclerosis, thus preventing heart disease

• Regulates and rebalances the gut

Both Staghorn Sumac and Smooth Sumac were often employed medicinally by several native North American Indian tribes who valued it especially for its astringent qualities. It is little used in modern herbalism. An infusion of the fruits has been used as a tonic to improve the appetite and as a treatment for diarrhoea. The berries are astringent and blood purifier. A tea made from the berries has been used to treat sore throats. The flowers are astringent and stomachic. An infusion has been used to treat stomach pains.

Sumac is used in Mediterranean countries such those of southern Europe and the Middle East. It is part of Za’atar, a blend that combines sumac, sesame seeds, salt and thyme and is used to spice up a variety of different dishes. It is worth getting to know this plant.

Staghorn sumac can be made into a drink. Heavy rain will wash away the tart covering of the sumac berries so be sure to harvest the berries before rain. Taste a berry for the lemony flavour.

Habitat of staghorn sumac:

Staghorn Sumac is a large shrub or small tree in the cashew family that typically grow 8-20 feet high, but can sometimes reach as far as 35 feet tall. New growth on the trees will be covered with a velvet-like hair, very similar to new stag horns that are also covered in velvet, hence the name). Staghorn Sumac is probably best recognized in the late summer to early fall when a large, red, fuzzy berry cluster rises from the tips of the trees.

Edible sumacs (including Smooth, Staghorn, and Fragrant Sumac) grow in most regions of southern Canada and the United States in open, sunny, moist habitats such as upland prairies, pastures, meadows, orchard edges, borders and openings of woods, along fences, roads, stream banks and along railroads

Usually found in upland sites on rich soils, but it is also found in gravel and sandy nutrient-poor soils. It grows by streams and swamps, along roadsides, railway embankments and edges of woods.

Edible parts of Staghorn and Smooth Sumac:

Fruit - cooked. A very sour flavour, they are used in pies. The fruit is rather small and with very little flesh, but it is produced in quite large clusters and so is easily harvested. When soaked for 10 - 30 minutes in hot or cold water it makes a very refreshing lemonade-like drink (without any fizz of course). The mixture should not be boiled since this will release tannic acids and make the drink astringent. Berries can also be dried and used as a spice.

Make Your Own Sumac-Ade

Sumac is also a well-known culinary spice, somehow managing to have a flavor both earthy and sour that pairs well with white meats and white wines.

Both chefs and herbalists might compare it to hibiscus: it tastes tart, cooling, and dry, with a very notable rosy astringency. Similar to hibiscus, sumac is a cool, drying, tonifying, and astringent herb.

The only thing that really sets it apart is an undertone of bitterness that somehow grounds sumac more than any other floral or berry astringent out there. For that reason, as a delicious sumac-ade drink, its flavor is unparalleled – and you know you’re not just drinking something tart and delicious, you’re also drinking a medicine!

• 5-10 sumac berry bunches, clusters, or “drupes” (twigs and all)

• 4-6 liters water

Note: the general ratio of water-to-berries should be about 1 parts berries to 2 parts water, when all is said and done, for the most flavorful and potent infusion.

-Harvest your sumac berry drupes by gently snapping them off by the stem from a mature shrub (of course, make sure the berries are red)

Staghorn Sumac in the Kitchen:

How To Make Sumac Spice: https://www.seriouseats.com/foraged-flavor-all-about-sumac

(which is Staghorn sumac or Rhus typhina) berries whole and dried/ground)

To make American sumac spice, remove the center stems of the red sumac cluster, so the berries are generally loose. Put them into a dehydrator or oven at the lowest setting for at least 3 hours or until dry. Grind the dried berries in a coffee or spice grinder, and push them through a mesh sieve to remove the larger seeds. Store in an airtight container. You can use this dried sumac spice to make fun stirfried dishes like my Three Sisters Sizzler dish or fun salads like the middle eastern Fattoush.

Recipe Ideas for making Middle Eastern Fattoush Salads:

FATTOUSH SALAD WITH ZAATAR CROUTONS : https://aspiceaffair.com/blogs/recipes/fattoush-salad-with-zaatar-seasoned-croutons

Fattoush Salad with zaatar seasoned croutons and a sumac infused vinaigrette : https://aspiceaffair.com/blogs/recipes/fattoush-salad-with-zaatar-seasoned-croutons

“NOT YOUR EVERYDAY FATTOUSH SALAD” : https://www.cherryonmysundae.com/2022/01/not-your-everyday-fattoush-salad.html

Make Your Own Sumac-Ade: https://healthstartsinthekitchen.com/sumac-ade-a-natural-alternative-to-kool-aid/?fbclid=IwAR2zGiDqhkey00bvkkdi9Y-9V-HWSG2kdyPPGh_X6Q77FnRkh_oJV90PK-M

Sumac is also a well-known culinary spice, somehow managing to have a flavor both earthy and sour that pairs well with white meats and white wines.

Both chefs and herbalists might compare it to hibiscus: it tastes tart, cooling, and dry, with a very notable rosy astringency. Similar to hibiscus, sumac is a cool, drying, tonifying, and astringent herb.

The only thing that really sets it apart is an undertone of bitterness that somehow grounds sumac more than any other floral or berry astringent out there. For that reason, as a delicious sumac-ade drink, its flavor is unparalleled – and you know you’re not just drinking something tart and delicious, you’re also drinking a medicine!

• 5-10 sumac berry bunches, clusters, or “drupes” (twigs and all)

• 4-6 liters water

Note: the general ratio of water-to-berries should be about 1 parts berries to 2 parts water, when all is said and done, for the most flavorful and potent infusion.

Sumac Apple Tart :

https://www.aarp.org/.../info-2019/foraging-for-flavor.html

How to avoid poisonous lookalikes:

You may have only ever heard the word sumac in conjunction with the phrase “poison sumac,” but this is grossly misleading.

All of the poisonous relatives of Sumac have white or yellowish berries. Remember that all edible sumac berries are red and you will never have a problem misidentifying them.

Poison sumac has off white berries and can only be found in very wet, marshy areas, so it takes some trying just to even find it. Staghorn and other varieties have red berries and aren’t at all poisonous.

Here are some links to where you learn more about Staghorn Sumac Berries:

https://www.motherearthliving.com/gardening/plant-profile/sumac1-zbw2002ztil/

http://www.bio.brandeis.edu/fieldbio/medicinal_plants/pages/Staghorn_Sumac.html

https://www.eattheweeds.com/sumac-more-than-just-native-lemonade/

https://thedruidsgarden.com/2020/07/19/sacred-tree-profile-staghorn-sumac-rhus-typhina/

https://www.eattheweeds.com/sumac-more-than-just-native-lemonade/

https://anisetozaatar.com/2019/08/26/foraging-and-preparing-staghorn-sumac-as-a-spice/

I hope you found this information helpful and will try foraging for some Staghorn Sumac (or other varieties of edible red sumac berries) and find peace of mind in the knowing that you are surrounded in food and medicine.

If we learn from Mother Nature and accept her open hand we can thrive and nurture our bodies in any and all situations (while staying guided by integrity and love).

We can align our wealth and health with the health and wealth of the living Earth and through merging with her regenerative capacity and inherent abundance we can become irrepressible.

We can lift ourselves and our communities out of the widespread modern day ‘poverty of plant knowledge’ and in doing so become resilient enough to survive and thrive no matter what life throws our way.

We are the ones we have been waiting for.

My family is from Vermont and New Hampshire. We moved away when I was very little (visiting and staying summers when we could, etc.), but after we moved back here (as an adult) in 1998, my uncle, who lived here all his life until his recent retirement, pronounced sumac as “shumac.” The plant and the word were new to me and I figured he must know, so I have called it “shumac” ever since - like sugar and sure. How do others pronounce it?

About 25 years ago, we found out about sumac lemonade and made some. We called it “sumac-ade,” and thought we had coined the word. I’m glad to see you calling it that too. :)