Day Ten: CATTAIL

She continues to offer to wrap humans in a soft and protective blanket woven together by her many gifts despite being misunderstood by many modern day humans

Offering an abundance of diverse forms of food, medicine, building materials and wisdom to increase our resilience in our lives on the Earth, we would be wise to learn to interact symbiotically with this plant as we head for uncertain times ahead.

Among the many gifts these magnificent and resilient plants offer is their proclivity to act as protectors of the water and the soil, offering their gifts of bioaccumulation for healing waters and soil that have been shown disrespect by humans.

This article will explore some of the endless gifts that Cattails offer us and our fellow beings through both the lens of the rich cultural history of how our ancestors perceived and interacted with this plant and modern science. I also share some fun recipe ideas at the end.

Cattails are nutrient-rich, containing carbohydrates, fats, protein, beta carotene, niacin, riboflavin, thiamin, potassium, phosphorus, magnesium, iron, manganese, polysaccharides and vitamin C.

Polysaccharides are known to help boost the immune response.

The jelly from between the young leaves (most plentiful in the Springtime) can be used as an itch or pain reliever. It has astringent, coagulant, pain-relieving and antiseptic attributes that can slow or stop bleeding, ease pain, and help clean wounds or scratches.

If you pull up the cattail roots, split them and mash them a little bit, it will produce a poultice. This poultice acts as an antiseptic and can be used to relieve pain and inflammation in cuts, wounds, burns, stings and bruises.

The cattail roots and stem can also be used to reduce fever, increase urine flow (diuretic), increase lactation, and treat dysentery.

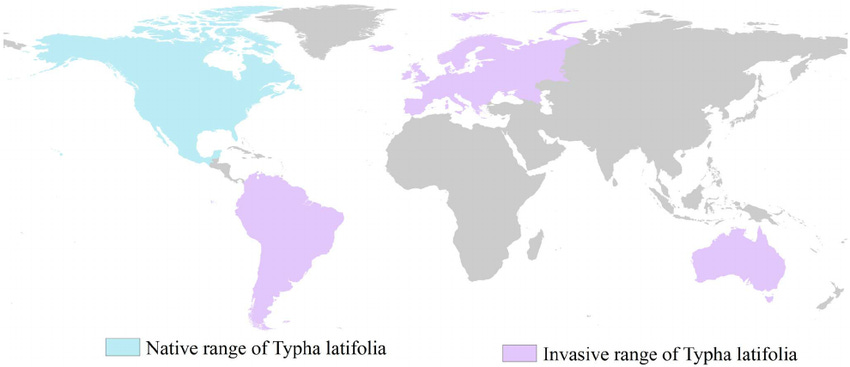

The two most abundant species of cattails in North America are Typha latifolia (common cattail) and Typha angustifolia (narrow leaf cattail). T. angustifolia may have been introduced from Europe. The two species also hybridize to form Typha x glauca. There are about 30 species in the genus Typha, and they share the family Typhaceae with just one other genus.

Because cattails spread so readily via rhizomes, prolific airborne seeds mostly serve to colonize new sites, away from the thick mass of already established cattails. The ability to dominate vast expanses of shoreline gives cattails an ‘invasive’ quality that often results in attempts at removal. Various human activities may be aiding their success. Regardless, they provide food and habitat to numerous species of insects, spiders, birds, and mammals. A cattail marsh may not be diverse plant-wise, but it is teeming with all sorts of other life.

Ethnobotanically speaking, it is hard to find many other species that have as many human uses as cattails. For starters, nearly every part of the plant is edible at some point during the year.

Cattails, for all their various uses, are often looked upon with distain and given the derogatory and misleading label ‘invasive plant’ often being seen as an annoyance by property owners and wetlands conservationists.

Let us now explore the rich history and many gift that Cattails share with the world as seen through the eyes of our ancestors so that we might dispel some common misconceptions about this wonderful plant.

History and Cultural Significance of Cattails:

Known as SȾÁ¸ḴEN to the indigenous peoples of North Western Turtle Island in SENĆOŦEN, Known as Pakwiyeshk and/or Bewiieskwinuk – to the Potawatomi/Ojibwe peoples of the Great Lakes regions in the Anishinaabemowin language. Known as Osháhrhe to the Mohawk people in the Kanien'keha language. Known as p’axłp to the Okanagan People. Known as סוף מצוי in Hebrew and افلح/ىدرب in Arabic. Known as τὐφη to the ancient Greeks and known as nGéadal (pronounced NYEH-tal) to my Celtic ancestors represented by the symbol shown in the image below in the Ogham Script.

The Druids sought to learn from the wisdom offered by the Cattail’s (and/or the Reed’s) flexibility, and how they are undaunted by rough winds or frozen ponds. Indeed, Aesop remarked on their strength in the fable of The Oak and the Reeds by saying

“An oak and a reed were arguing about their strength. When a strong wind came up, the reed avoided being uprooted by bending and leaning with the gusts of wind. But the oak stood firm and was torn up by the roots.”

— Aesop

Who is mightier, the yielding or the unbending?

Meaning to the Druids: Swiftness and speed, the idea that things are moving forward, perhaps rapidly. Transformation. Flexibility, adaptability and the healing that only changing circumstances can bring.

In Druidic metaphysical symbolism, when cattail appears in your life, it is said to often indicate a need to rebuild that which was destroyed. Think before you act, and be proactive rather than reactive.

Its spiritual implications are described as offering the following message: Although you may encounter some bumpy spots in the road, ultimately your spiritual journey will be a fruitful and productive one. Understand that the lessons you learn on your way are equally as important–maybe even more so–as the destination itself.

The reed is also connected with the Celtic story teller, and by extension the Welsh bard. They bear the tale of the bard, figuratively in the form of the song that instruments made from the stem and literally in the case of Taliesin. In ‘the Book of Taliesin’ the magical child was found floating in a basket of woven reeds in the same way that Moses was found in the bullrushes/cattails of the Nile.

“The family of reeds

watch over the wetlands.

Standing-tall sentries of rivers, lakes and ponds

blessed by the omnipresent hands

of our dear Goddess, who cares for them all:

her reeds, rushes and cattails

which thrive along swamps.

The Celts have long-honored

these most unique of plants

which make music in the wind

and most gracefully bend.”

Watchers of the Wetlands – by Scott B. Stewart

The Cattail and/or Reed also had others uses for my Celtic ancestors. Including their edible rhizomes, which archaeological evidence suggests may have been eaten thirty thousand years ago in Europe.

Catriona McDonald of “The Druid’s Well” shares some of her insights about Cattails by saying:

“Cattails, like birch and mugwort, are pioneers, able to inhabit areas recently destroyed so that other species may follow. Even dead stalks can transfer oxygen down to the roots, and the seeds can survive for years until the right conditions are ready for them to sprout. Cattails are survivors, like so many so-called “weeds,” and protect and shelter all manner of wildlife and birds within their vast colonies. Many lessons may be won from watching them: how to bend, how to survive, how to expand, and how ultimately to thrive. Their song is not a loud one, but its sighs can inspire and heal with incomparable gentleness. Never mistake humility for passivity or gentleness for weakness. Cattails may not be flashy, but they drink from the Well and we can’t forget the depths of the wisdom that brings.”

The ancient peoples of Turtle Island (aka “North America”) or “Mshike Mnise” in Bodwéwadmimwen (the Potawatomi language) also have a rich history of interacting with Cattails and recognizing their many gifts.

In Potawatomi, the word for cattail, bewiieskwinuk, translates to “we wrap the baby in it” and in the Mohawk language, cattail (Osháhrhe) translates to “the cattail wraps humans in her gifts” as if we were her babies.

Robin Wall Kimmerer comments on this in her book Braiding Sweetgrass by saying

“In that one word, we are carried in the cradleboard of Mother Earth.”

What a beautiful and apt description of this plant for as you will see as you read this article, Cattails do indeed offer to lovingly envelop humanity with her many gifts, providing both our ancestors and us with loving support and nourishment to be able to survive and thrive in challenging situations.

The indigenous peoples of turtle island had many uses for this plant. They harvested food from the roots, vegetable from the stalk, pollen for flour, edible flower stalks, seeds for tinder or diapers, leaves for cordage and mats and baskets, torches from seed heads, aloe-like medicine from the goo which looks slimy but feels great on bug bites...and more.

Modern academics say “if left unchecked, cattails can clog waterways, harm agriculture and fisheries, and host other species, such as blackbirds, which can cause further crop damage. Fast growing, tall standing, and rapidly spreading via both seeds and specialized root systems, cattails have perfected numerous adaptations to invade, occupy, and thrive in wetland ecosystems, with consequences for the agricultural industry”

And yet, “this is all good for the plant, of course—and it’s good for people,” insists Kimmerer, a State University of New York Distinguished Teaching Professor of Environmental Biology and an enrolled member of the Citizen Potawatomi Nation.

Below is a section from Robin Wall Kimmerers book where she goes into more depth on the cultural significance and wisdom offered by the Cattail

This view of cattails as good for the people contravenes the widely held view of them as invasive. Indeed, Indigenous knowledge has been delegitimized in the eyes of what we now know simply as “science.” Invasiveness is an example of an ecological concept that has been widely theorized and extrapolated upon within the scientific establishment but which may be flawed at its base.

Cattails provide den-building materials for the wazhushk (meaning “muskrat” in zhaaganaashiimowin) and safe cover for deer. Understanding the relationship between native and ‘non-native’ species at all levels of an ecosystem is a complex task. There are numerous variables: geographical isolation, behavioral nuances, resource availability, climate variation, competition, and migration, all of which modulate species interactions over various space and time scales.

Growing evidence of successful coexistence and mutualism between native and ‘non-native’ species began to emerge in a number of studies around the turn of the century, generating profound criticisms the widely accepted hypothesis of ‘invasion’. Evidence of cooperation can also be found in the way native and non-native species work together to enhance nitrogen fixation, habitat modification, and pollination. In 2018, Northfield et al. documented indirect interactions showing that native species facilitate non-native invasion.

Considerations of coexistence and cooperation among humans, plants, and animals, though absent in the work of most Western scientists, are central to the traditional knowledge and science of Indigenous Anishinaabe communities, who live in the region north of the Great Lakes. Such knowledge offers a more nuanced perspective on species migration, going beyond the native/non-native and useful/harmful binaries, as was documented in the work by Professors Nicholas Reo (a citizen of the Sault Ste. Marie Tribe of Chippewa Indians) and Laura Ogden.

Professors Reo and Ogden conducted ethnographic research with Anishinaabe communities and found that despite having been greatly affected by ecosystem disruption from settler colonial species introduction, these communities view arrivals of new species as part of the natural migratory processes of plant and animal nations, without problematizing these processes. The Anishinaabe do not consider non-native species a nuisance; rather, they are more concerned with the land ideologies of the colonists who think of non-native species as “invaders.” According to Reo and Ogden, Anishinaabe knowledge values observations that can help to generate understandings of why new plants and animals have inhabited their lands and to investigate the nature of novel relationships between humans and newly-arrived species.

“I wonder if anyone has bothered to ask the Asian carp or the hybrid cattail why they are here?” Bud Biron, a cultural educator from the Sault Ste. Marie tribe, asked Reo and Ogden. Professor Enrique Salmón presented a similar concept to describe the perception by Indigenous communities of the other species surrounding them as kin: “kincentric ecology.” “Indigenous people view both themselves and nature as part of an extended ecological family that shares ancestry and origins,” he says, which supports their acceptance of the new species and builds the foundation of Indigenous ethical practices and stewardship. Dr. Deborah McGregor, Anishinaabe professor and Canada Research Chair in Indigenous Environmental Justice, has illustrated the Indigenous ideology buen vivir, which “calls for ‘living well’ within a community that extends to the natural world,” and viewing relationships between human and non-human beings as central to environmental sustainability. Unfortunately, Anishinaabe ecological theories and perspectives such as these are often devalued by colonially educated scientists because of their basis in community knowledge and because of interpretation biases deeply rooted in a colonial perspective. As a result, these perspectives are underrepresented in colonial scientific publications, which tend to perpetuate individualist and reductionist science.

Given that modern science has confirmed how powerful Cattails are in offering their gifts of phytoremediation (Bioremediation and Biodegradation) to help heal anthropogenically polluted landscapes, waters and soils, part of the answer to the question of “why are the cattails here” may be right in front of us.

Robin Wall Kimmerer wrote more recently about Cattails explaining “there are so many Native science teachings held in that single plant. I've heard two different Potawatomi names for her : "Shelter weed" and "we wrap the baby in it". Cattails takes good care of us and we can reciprocate. Cattails grow in nearly all types of wetlands, wherever there is adequate sun, plentiful nutrients, and soggy ground. Midway between land and water, freshwater marshes are among the most highly productive ecosystems on earth, rivaling the tropical rainforest. People valued the supermarket of the swamp for the cattails, but also as a rich source of fish and game. Fish spawn in the shallows; frogs and salamanders abound. Waterfowl nest here in the safety of the dense sward, and migratory birds seek out cattail marshes for sanctuary on their journeys.”

Cattail leaves can be used to make cords, mats, baskets, thatch, and many other things.

Kimmerer writes about the excellent wigwam walls and sleeping mats that weaved cattail leaves make:

“The cattails have made a suburb material for shelter in leaves that are long, water-repellent, and packed with closed-cell foam for insulation. … In dry weather, the leaves shrink apart from one another and let the breeze waft between them for ventilation. When the rains come, they swell and close the gap, making the [wall] waterproof. Cattails also make fine sleeping mats.

The wax keeps away moisture from the ground and the aerenchyma provide cushioning and insulation.”

The fluffy seeds make great tinder for starting fires, as well as excellent insulation and pillow and mattress stuffing. The dry flower stalks can be dipped in fat, lit on fire, and used as a torch. Native Americans used crushed rhizomes as a poultice to treat burns, cuts, sores, etc. A clear gel is found between the tightly bound leaves of cattail. Kimmerer writes, “The cattails make the gel as a defense against microbes and to keep the leaf bases moist when water levels drop.” The gel can be used like aloe vera gel to soothe sunburned skin.

As noted above, Cattails, also known as bulrushes, had a number of practical uses in traditional Native American life: cattail heads and seeds were eaten, cattail leaves and stalks were used for weaving mats and baskets, cattail roots and pollen were used as medicine herbs, and cattail down was used as moccasin lining, pillow stuffing, and diaper material. In the southwestern tribes, cattails also have more symbolic meaning.

Cattails are associated with water and rain by the Pueblo tribes, and used ceremonially in rain dances. The Mexican Kickapoos associate cattails with water serpents and make offerings to the snake people before gathering cattails. The Navajo believed cattail leaves were a protective charm against lightning. And many southwestern tribes used cattail pollen as a traditional face paint.

The Cattail is also used as a clan symbol in some Native American cultures. Tribes with Cattail Clans include the Osage tribe.

Native American Legends About Cattails

Lox and the Black Cats:

In this Wabanaki story, the trickster villain Lox uses cattail plants to fool his enemies and escape punishment.Manabush and the Cat-tail Reeds:

Algonquian stories about the culture hero being tricked by some swaying cat-tails.

Recommended Books of Cattail Stories from Native American Myth and Legend:

Manabozho and the Bullrushes:

Charming picture book about a hero dancing with the cattails, by an Ojibwe author and illustrator.Strength of the Earth: The Classic Guide to Ojibwe Uses of Native Plants:

Book of Ojibwe traditions about the meaning of cat tails and other woodland and prairie plants.Native Plant Stories:

Excellent collection of Native American stories about plants, by Abenaki storyteller Joseph Bruchac.Native American Ethnobotany:

Comprehensive book on the names and traditional uses of plants throughout Native North America.

Cattail (aka Bulrush) even plays a part in the bible as Moses was described as a child who was adopted by Pharoah's daughter and raised as an Egyptian. In the book of Exodus, he is left in a basket in a clump of reeds (bulrushes), but he is never abandoned. The story of Moses starts in Exodus 2:1-10. By the end of Exodus 1, the pharaoh of Egypt (perhaps Ramses II) had decreed that all the Hebrew boy babies were to be drowned at birth. But when Yocheved, Moses' mother, gives birth she decides to hide her son.

After a few months, the baby is too big for her to hide safely, so she decides to place him in a caulked wicker basket in a strategic spot in the cattails that grew along the sides of the Nile River (often referred to as bulrushes), with the hope that he will be found and adopted. To ensure the baby's safety, Moses's sister Miriam watches from a hiding place nearby. The baby's crying alerts one of the pharaoh's daughters who takes the baby.

Cattail nutrition:

Cattails shoots are nutrient-rich, containing beta carotene, niacin, riboflavin, thiamin, potassium, phosphorus, and vitamin C.

The sweet fiber in cattail roots provides an abundance of starchy carbohydrates; the new stalk shoots can be eaten to obtain Vitamins A, B, and C, potassium, and phosphorous; and the seeds can be ground and used as a flour substitute.

The pollen makes an excellent high-protein substitute for flour in your favorite baked goods.

Health Benefits of Cattail

Some of the most interesting health benefits of cattail include its ability to reduce pain, speed wound healing, prevent infections, and slow bleeding.

Cattail is a very healthy and nutrient dense plant which grows throughout the much of the world. Some of the popular health benefits of consuming cattail are listed below in detail:

1. Improves digestion

Cattail consists of good amount of both soluble and insoluble fiber which is essential for improving the digestion process. Soluble fibers counter the absorption of cholesterol and insoluble fiber encourage the movement of waste out of the system. This leads to reduced chances of constipation or even hemorrhoids. So include cattail in your diet to reduce all the digestion related problems.

2. Calorie rich

In case you are underweight and want to gain some weight, a mixture of Cattails rich diet together with a wholesome meal is the best method. Cattail being rich in carbohydrates and calories enables the weight gain process. Therefore it is one of the fruitful options for underweight people to gain required body weight.

3. Skin Health

Cattail consists of huge amount of nutrients and organic compounds which contributes to its effect on the skin, mainly its ability to heal boils, sores, and decrease the appearance of scars. Cattail jelly can be used topically for insect bites, but the flour also has anti-inflammatory potential that help to decrease the pain as well as severity of those affected areas.(1)

4. Hypertension

Adrenal glands are provided the appropriate support to decrease levels of stress by the content of protein and carbohydrates present in Cattail. It helps to improve the metabolism rate and thereby reduces stress.

5. Diabetes

Phytochemicals are required to streamline and maintain the absorption of insulin. A regular intake of Cattail can make your system combat diabetes mellitus, which is non-insulin dependent. So it is fruitful to consume cattail on a regular basis to combat diabetes.

6. Cancer Prevention

However this area of research is comparatively new and somewhat controversial, research is ongoing regarding cattails ability to prevent cancer. Chinese researchers are heading up exciting new area of study, but early results are promising for its antioxidant effect on cancerous cells.(2)

7. Atherosclerosis

LDL is decreased by intake of Cattail on account of the composition of Vitamin C, carotenoids and bioflavonoid. These elements make certain that the risks of cardiovascular diseases are reduced and the LDL is washed out of the system. Apart from that cholesterol absorption is also reduced. It means a reduced risk of developing atherosclerosis.

8. Cardio tonic and lipid-lowering effects

Cattail comprises of a certain composition of compounds, which help in decreasing the lipids in the body and even dilating the coronary artery. It is used in the treatment of heart diseases like angina, hyperlipidemia. Moreover, it is even used to dissolve stasis. It helps to reduce the deposition of lipids on the walls of the arteries. Hence, it prevents the incidence of heart diseases.

9. Antiseptic Application

Cattail is popular due to its natural antiseptic property, which has come in handy for numerous cultures for generations. The jelly-like substances that you can find in between young leaves are used on wounds and other areas of the body where foreign agents, pathogens, or microbes might do damage in order to protect our system. This same jelly from the cattail plant is known as a powerful analgesic and can be ingested or applied topically to relieve pain and inflammation.(3)

10. Steady increase in energy

As we all know that carbohydrates are a rich source of energy. Cattail consists of good amount of carbohydrate content. It means it has the ability to offer you greater levels of energy and even replenish energy levels if deficient from time to time. Since Cattail is made up of complex carbohydrates, the breakdown is rather slow, which means, you would have all the energy you need throughout the day.

11. Slow Bleeding

Various parts of the cattail have coagulant properties, meaning that they slow down the flow of blood and prevent anemia. This can be effective if you’re wounded, but also if you suffer from heavy menstrual bleeding, since it can lessen the severity. But it is potentially dangerous for people who already have moderately slow circulation, as it efficiently slows down the blood, while simultaneously stimulating coagulant response in the skin.(4)

Habitat of the herb:

The Common Cattail (Typha latifolia) and its brethren Narrowleaf Cattail (Typha angustifolia), Southern Cattail (Typha domingensis), and Blue Cattail (Typha Glauca) are all edible and have representatives found throughout North America and most of the world.

Shallow water up to 15cm deep in ponds, lakes, ditches, slow-flowing streams etc, succeeding in acid or alkaline conditions.

Cattails are frequently eaten by wetland mammals such as muskrats, which also use them to construct feeding platforms and dens, thereby also providing nesting and resting places for waterfowl. Cattails provide both food and shelter for many other animals including beavers, some fish species and Canada geese.

Like many other wetland plants, cattails bio-accumulate toxins. When harvesting cattails for consumption, it is important to collect them from a clean source, away from roads and buildings. But because cattails absorb water pollutants, this also makes them very useful in keeping water systems clean. Urban gardeners frequently plant cattails in small ponds as a barrier between the exhaust fumes from roadways and fruit trees or vegetable plots. Cattails have also been successfully used in cleaning up a range of toxins that have leached into waterways, such as arsenic, pharmaceuticals, explosives, phosphorous, and methane. Cattails not only gift humanity food, shelter, warmth and medicine, she also offers her gifts to clean up the mess we have made of Mother Earth’s sacred waters and soils.

Edible parts of Cattail:

Roots - raw or cooked. They can be boiled and eaten like potatoes or macerated and then boiled to yield a sweet syrup. The roots (called rhizomes) are harvestable throughout the year, but they’re best in the fall and winter. To prepare a cattail root, clean it and trim away the smaller branching roots, leaving the large rhizome. You can grill, bake or boil the root until it’s tender. Once cooked, eating a cattail root is similar to eating the leaves of an artichoke – strip the starch away from the fibers with your teeth. The buds attached to the rhizomes are also edible!

The roots can also be dried and ground into a powder, this powder is rich in protein and can be mixed with wheat flour and then used for making bread, biscuits, muffins etc.

To make flour: You can also use the roots to make flour, used as a thickening agent in cooking. Scrape and clean several cattail roots. Place roots on lightly greased cookie sheet in a 200º F oven to dry overnight. Skin roots and remove fibers. Pound roots until fine. Let stand overnight to dry. Sift, and it’s ready to use.

One hectare of this plant can produce 8 tonnes of flour from the rootstock. The plant is best harvested from late autumn to early spring since it is richest in starch at this time. The root contains about 80% carbohydrate (30 - 46% starch) and 6 - 8% protein. The roots are also what contains the highest amount of polysaccharides in the plant.

Young shoots in spring - raw or cooked. An asparagus substitute. They taste like cucumber. The shoots can still be used when they are up to 50cm long.

Base of mature stem - raw or cooked. It is best to remove the outer part of the stem. It is called "Cossack asparagus". Immature flowering spike - raw, cooked or made into a soup. It tastes like sweet corn.

Seed - raw or cooked. The seed is rather small and fiddly to utilize, but has a pleasant nutty taste when roasted. The seed can be ground into a flour and used in making cakes etc. An edible oil is obtained from the seed. Due to the small size of the seed this is probably not a very worthwhile crop.

Pollen - raw or cooked. The pollen can be used as a protein rich additive to flour when making bread, porridge etc. It can also be eaten with the young flowers, which makes it considerably easier to utilize. The pollen can be harvested by placing the flowering stem over a wide but shallow container and then gently tapping the stem and brushing the pollen off with a fine brush. This will help to pollinate the plant and thereby ensure that both pollen and seeds can be harvested.

• Cattail Corn on the Cob: If you pick the catkins in the spring, while they’re still green and hidden in the leaves, you can eat them just like corn on the cob.

Boil the catkins until they’re heated through, and then serve with butter, salt, and pepper. They make a nice side to a main dish.

• Baking with Cattail Pollen: Once the catkins mature – usually by the end of June – you can harvest pollen by bending the catkins into a bag and shaking the pollen off. Cattails produce a lot of pollen, so you’ll end up with several pounds in no time. The pollen makes an excellent high-protein substitute for flour in your favorite baked goods.

• Shoots and Stalks: In the spring, you can harvest both the new shoots and the white parts of the cattail stalks near the roots. You can cook and serve the shoots and stalks like asparagus, or you can clean them, slather on some peanut butter and eat them fresh.

Cattail in the kitchen

Fermented Cattail Shoots : https://www.growforagecookferment.com/fermented-cattail-shoots/?fbclid=IwAR0LyEdTlxABANIMnzGL23ehn0fTKSbvT8Rt9D2EFgEwDBHCA2FLln3oSpc

Cattail Pollen Pancakes: https://www.natureoutside.com/how-to-make-cattail-pancakes/?fbclid=IwAR3w2G5RosgdraawKjZuXSJKjszFqTQyyJkCY1q3rZw2f1HFx4Tf2MB5d3A

Cattail and Oyster Mushroom Stir Fry: https://www.thetasteofmontana.com/recipes/cattail-hearts-and-wild-oyster-mushrooms

Cattail Pollen Pasta: https://honest-food.net/cattail-pollen-pasta-recipe/?fbclid=IwAR0DMXkFe1Yo--BRA6PUO8R_vvsxGE80yQozFwCcAfS8ozMW8rFS7CG2G3g

Wild Rice Pilaf with Cattail Shoots and Shiitake Mushrooms: https://www.spokesman.com/stories/2015/jun/03/cook-with-cattails-no-cing-required/?fbclid=IwAR1ZVBZy9lz1dgrD9Z-Fe6u8e-xhkoP5eq91RsYL468BOeNMdzHoVXNVkrQ

Pickled Cattail Shoots: https://www.motherearthnews.com/real-food/pickled-cattail-shoots-recipe-zerz1804zmos/?fbclid=IwAR0f-9AqBxEz9nuPiqJ3zom_VPDJ0GouaBZuDC79ljPliUGbmhkKCm6_vfU

Scalloped Cattails

Take two cups of chooped cattail tops and put them into a bowl with two beaten eggs, one-half cup melted butter, one-half teaspoon each sugar and nutmeg and black pepper. Blend well and add slowly one cup of scalded milk to the cattail mixture and blended. Pour the mixture into a greased casserole and top with grated Swiss cheese —optional — and add a dab of butter. Bake 275 degrees for 30 minutes.

Cattail Pollen Biscuits

The green bloom spikes turn a bright yellow as they become covered with pollen. Put a large plastic bag over the head (or tail) and shake. The pollen is very fine, resembling a curry-colored talc powder. Pancakes, muffins and cookies are excellent by substituting pollen for the wheat flour in any recipe. Cattail Pollen Biscuits: Mix a quarter cup of cattail pollen, one and three-quarters cup of flour, three teaspoons baking powder, one teaspoon salt, four tablespoons shortening, and three quarters a cup of milk. Bake, after cutting out biscuits, in 425-degree oven for 20 minutes. For an even more golden tone, you may add an additional quarter cup of pollen.

Seshelt Chowder

Ingredients:

4 large cattail roots, roasted and dried (using oven method, above)

5 cups water

2 teaspoons salt

1 ½ pounds roughly cut, fresh salmon

¼ teaspoon fresh pepper

Directions:

Simmer the cattail roots in water for 40 minutes. Add remaining ingredients and simmer for 10 minutes.

Cattail Casserole

Two cups scrapped spikes, one cup bread crumbs, one egg, beaten, one-half cup milk, salt and pepper, one onion diced, one-half cup shredded cheddar cheese. Combine all ingredients in a casseroles dish and place in an oven set to 350 degrees for 25 minutes. Serve when hot.

Other uses for Cattail:

Shelter Material

The green leaves can be cut and woven together into shingle like squares for covering a shelter roof. The material will provide protection from the rain, snow and wind even after it has dried. Weave a sleeping mat by making two long mats. Connect the mats on one side so it can be folded like a sleeping bag. Before folding over fill one side with pine boughs or other material suitable for sleeping on and then fold the empty half over and tie off so the “stuffing” is secured inside. You can fold the mat up and carry it with you if you have to break camp for another location.

Also see: Heating Survival Shelter with Hot Stones, Cattail Roots, Hand Drill Fire

Baskets or Packs

You can get creative and weave baskets or small packs for carrying food or other items. Cross a number of leaves together and once you have the base the size you want you would fold the pieces up and then weave around the sides to secure the shape. You can easily weave handles or straps into the basket/pack. The basket will become stronger as the cattail leaves dry and harden.

How-To Process Cattail Leaves For Weaving : https://www.wickerwoman.com/articles/processing-cattail-leaves

Harvesting Cattails For Basketry: The Basics and Beyond: https://katiegrovestudios.com/2017/06/01/harvesting-cattails-101/

As Cordage

Peel strips from the leaves and allow to dry somewhat. Once dried braid at least three strips together to create a line for fishing or use in shelter building.

Fire Starting and Insulation

The head of the cattail after it has turned dark brown will have “fluff” inside, which is excellent tinder. Even after a rain the tinder may still be dry inside the head and if not remove and place in a pocket to dry out by allowing the clothing to absorb the moisture as long as the weather is warm. The fluff can also be used as insulation for hats and shoes and if you have enough of it, you could make pillows and even stuff a poncho or tarp to make a mattress.

The head can also be covered in pine resin to make a torch. Cut off enough of the stalk for a long handle with the head attached. Roll the head in pine resin and light when needed.

Papermaking from Plant Materials (Cattail Fibers) : https://thedruidsgarden.com/2012/07/09/papermaking-part-ii-papermaking-from-plant-materials-cattail-fibers/

Identification:

Cattails are probably the most easily recognized and known aquatic plant. They like to grow in large groups in shallow water or slow-moving waters exposed to sunlight.

Cattails are readily identified by the characteristic brown seed head. There are some poisonous look-alikes that may be mistaken for cattail, but none of these look-alikes possess the brown seed head.

Blue Flag (Iris versicolor) and Yellow Flag (Iris pseudoacorus) and other members of the iris family all possess the cattail-like leaves, but again, none possesses the brown seed head. All members of the Iris family are poisonous. Another look-alike which is not poisonous, but whose leaves look more like cattail than iris is the Sweet Flag (Acorus calumus). Sweet Flag has a very pleasant spicy, sweet aroma when the leaves are bruised. It also does not posses the brown seed head. Neither the irises nor cattail has the sweet, spicy aroma.

For more information on Cattail:

https://thedruidsgarden.com/2012/12/11/papermaking-iii-cattail-leaf-paper-a-learning-experience/

https://magazine.scienceforthepeople.org/vol24-3-cooperation/asking-the-cattails-why-they-are-here/

https://www.mtpr.org/arts-culture/2018-04-02/cattail-plant-of-a-thousand-uses

https://www.farmersalmanac.com/cooking-wild-edible-cattails-25374

https://www.backdoorsurvival.com/guide-to-using-cattails-a-survivalists-dream-plant/

https://ethnobiology.org/sites/default/files/pdfs/JoE/21-2/Ostapkowicz-etal.pdf

https://www.growforagecookferment.com/foraging-for-cattails/

http://www.nativetech.org/plantgath/cattail.htm

I hope you found this information helpful and will try foraging for some Cattails and find peace of mind in the knowing that you are surrounded in food, shelter building materials and medicine.

If we learn from Mother Nature and accept her open hand we can thrive and nurture our bodies in any and all situations (while staying guided by integrity and love).

We can align our wealth and health with the health and wealth of the living Earth and through merging with her regenerative capacity and inherent abundance we can become irrepressible.

We can lift ourselves and our communities out of the widespread modern day ‘poverty of plant knowledge’ and in doing so become resilient enough to survive and thrive no matter what life throws our way.

We are the ones we have been waiting for.

And, oh, any mention of Druids always gets my attention! :)

Oh my God. You surprised me with this one, Gavin, and now I've learned SO MUCH about Cattails! There are so many across the road from me. I'm going to search for some brown heads to try as tinder for the fire. Thank you! :)