Amaranth Seed, Trail Of Tears and Hokkaido Black Soy Bean Miso Paste

This post shares another recipe from my book that empowers you to be able to transform seasonal harvests in an extremely nourishing format that can be preserved for the long term

"Reclaiming our food and our participation in cultivation is a means of cultural revival, taking action to break out of the confining and infantilizing dependency of the role of consumer (user) and taking back our dignity and power to become producers and creators. Though affluent people have more food choices than the people of the past could ever dream of, and one persons labor can produce more 'food' today than ever before, the large scale, commercial methods and systems that enable these phenomena are destroying our Earth, destroying our health, and depriving us of dignity. With respect to food, the vast majority of people are completely dependent for survival upon a fragile global infrastructure of monocultures, synthetic chemicals, biotechnology, and transportation.

Moving towards a more harmonious way of life and greater resilience requires our active participation. This means finding ways to become more aware of and connected to the other forms of life that are around us and that constitute our food---plants and animals--- as well as bacteria and fungi--- and to the resources, such as water, fuel, materials, tools and transportation, upon which we depend. We can become creators of a better world, of better and more regenerative food choices, of greater awareness of resources, and of community based upon sharing. For culture to be strong and resilient, it must be a creative realm in which skills, information, and values are engaged and transmitted; culture cannot thrive as a consumer paradise or spectator sport. Daily life offers constant opportunities for participatory action. Seize them."

― Sandor Ellix Katz (Author of "The Art of Fermentation" )

This recipe is something I have enjoyed building on and making different variations of depending on what we have growing in the garden in season. The hearty and nourishing soups this versatile preserve allows one to make at a moment's notice and throw in a thermos are very helpful to those working a busy schedule outside and needing to stay warm and energized.

Miso (味噌) is a Japanese fermented bean paste made by inoculating cooked beans with Koji (Aspergillus oryzae, which is a filamentous fungi aka ‘good mold’ species) and LAB and aging for 6 months plus. As with many other food ferments this process allowed for seasonal abundances to not only be preserved, but their flavor and nutritional bioavailability to be augmented (allowing for a diversification of culinary uses and access to nutritious food during winter months when no crops were coming in).

One of the reasons I chose to dive into the traditional foods of Japan to inspire the creation of this recipe (aside from loving the flavor and nutrition) is that I feel ancient Japan offers some wisdom on how we can move our society in a more sustainable (or better yet Regenerative) direction. The practical application of low-zero waste urban/agricultural systems were especially evident and critical during the Edo period (CE 1603–1868) in Japan. This was a time when environmental/soil degradation and deforestation led to the people of Japan realizing they would need to give back to the soil is they wanted to prevent the collapse of their civilization.

I will share more on that part of Japanese history and it’s implications for the similar modern day predicament we find ourselves in today in the west later in this post. But first, what is miso paste?

Several different cultures have their own versions of fermented bean paste (ranging from the more spontaneous Korean Doenjang (된장) and Chongkukjang (청국장) to the Chinese Doubanjiang (豆瓣酱) to the Indonesian Tempeh (Témpé) each offering their own unique flavors and having an illustrious history reaching back hundreds to thousands of years. I chose to start with Miso as it is something I became familiar with as a young child going to Japanese restaurants with my family in Whistler and Vancouver BC but there are a range of different ways to ferment beans each offering unique practical benefits, distinct flavor profiles and opportunities to learn about ancient cultures from all over the world.

It is worth noting that while soybeans (and several other beans) are excellent sources of protein and other valuable nutrients they also often contain ‘anti-nutrients’ (especially soybeans) which can prevent the body from being able to absorb important minerals like iron. The fermentation process neutralizes these ‘anti-nutrients’ while simultaneously increasing the bioavailability of the other nutrients via the action of several key fermenting organisms. Thus, making one’s garden bean harvests into paste is not only a great way to diversify flavors and learn about other cultures, it also allows you to get more nutrition out of your beans, minimizes flatulence and provides another means for preserving other crops alongside your beans.

Our path to make miso paste was motivated by our love for miso soup, my want to minimize ordering food from far away places, and a huge harvest of heirloom beans and Amaranth we had in 2019.

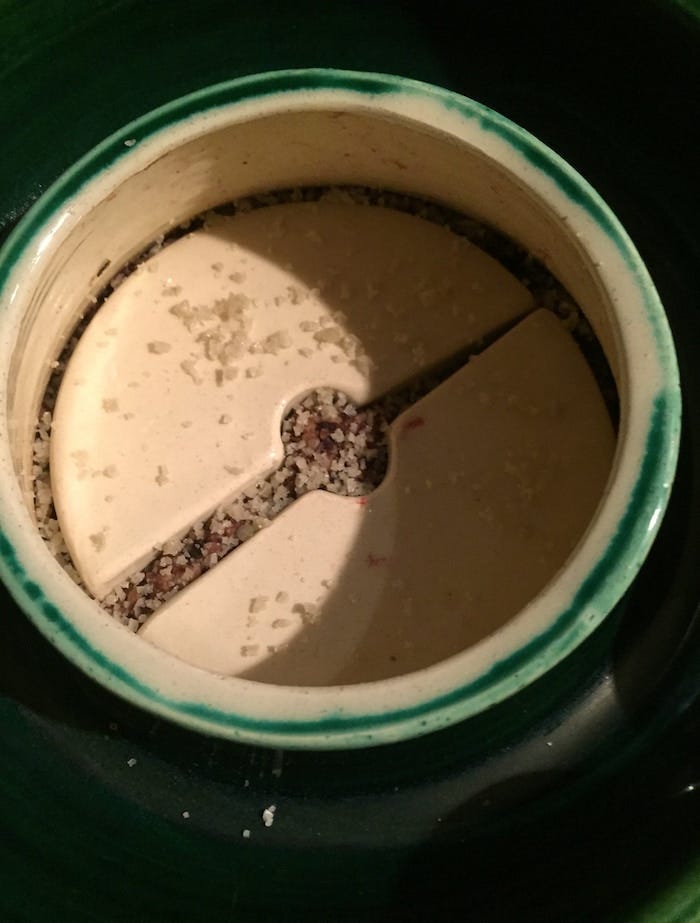

The day we opened our first homemade batch of miso paste was an auspicious day.. a moment of truth and affirmation. I`ll admit I was a bit nervous when I was unsealing the crock that contained our experimental Miso paste (that had been fermenting for close to 7 months untouched). The suspense was high.. when I opened the lid and was greeted by a beautiful unami/tamari/Koji fragrance I felt a deep sigh of relief that my longest aged food ferment to date had likely been a success! Then when I tried tasting some of the raw paste and was overwhelmed with a spectrum of rich enticing savory and sweet flavor notes and invited into a world of unami awesomeness I knew for certain it was a good batch

I was able to harvest about 500ml of delectable Tamari from our first batch (known as "liquid gold" to some, being the purest probiotic rich form of 'soya sauce') from the surface of the fermentation vessels and packed the miso paste into jars to be stored and further aged.

The aroma and flavor is hard to describe, it is very enticing, approachable and offers different layers of complexity. The texture is wonderfully diverse (as I only lightly mashed the soybeans and trail of tears beans) so there are discernable pieces in the finished paste that offer their own unique flavor profile in each spoonful.

I basically followed the recipe as far as the ratio of legumes to salt to koji from "The Art Of Fermentation" but I included non-traditional legumes and grains alongside the traditionally used soybeans.

Ingredients:

Here are the basic ratios of Koji to legumes to salt (from Sandor Katz “The Art Of Fermentation”) which I use as a general guideline for making my miso pastes. If you are adding experimental/optional ingredients such as ancient grains, mushrooms, herbs, spices or vegetables these would be considered at part of the legumes portion of the equation so adapt your ratio of beans accordingly. The benefit of using higher proportions of Koji is that they generally require much less salt and do not require cool cellar conditions for long aging. With regards to adding mushrooms, veggies, fruit, herbs or spices I suggest these ingredients do not exceed more than 10% of the total volume of any given batch (as to minimize the chance of throwing off the fermentation). There is wiggle room for experimentation on either side of this spectrum, but here are the basic numbers to get you started on your miso making journey.

“Sweet Miso” (short term fermentation):

-2 pounds (1kg) legumes (and/or other carbohydrate/protein containing items)

-2 pounds Koji (1kg) (typically rice inoculated/colonized with Aspergillus oryzae)

-6% Salt (or .25 pounds/120 grams)

Dark Miso (long term fermentation):

-2 pounds legumes (1kg) (and/or other carbohydrate/protein containing items)

-1 pound Koji (500 grams) (typically rice or barley inoculated/colonized with Aspergillus oryzae)

-13% Salt (or .4 pounds/200 grams)

For making our Amaranth, Trail of Tears and Hokkaido Black Soy Bean Miso Paste the ingredient ratios looked like this:

- 1.5 lb dry Golden Giant Amaranth Seed

- 1.5 lb dry Hokkaido Black Soy Beans (these heirloom soy beans have an illustrious history in Japan and are rich in antioxidants)

- 1 lb dry Trail Of Tears Beans

- half cup of dried Atlantic wakame flakes

- a few tablespoons of a raw mature batch of miso (for inoculating with good bacteria specialized for metabolizing legumes)

- 5 lbs dry Koji (rice/barley that had been fully colonized by Aspergillus oryzae and then dried)

-10% sea salt (0.63 lbs or 286 grams) (plus extra for sprinkling on top of the miso paste in the crock)

Directions:

Start by soaking your soybeans (and any other beans) overnight by putting them in a large ceramic bowl and covering in water by at least two inches, let sit in your fridge overnight. Next, drain and rinse off the soybeans.

Then place in a large pot and with 3 times the volume in water as there are beans. Bring the water to a boil (if any foam surfaces scoop this off and discard) and then turn down to simmer for about 2-3 hours (or up to 6 hours depending on the type of bean) checking intermittently to stir avoiding sticking and checking how cooked the beans are. Overcooking is not a problem just be sure to check so the beans do not burn onto the pot. Cook the non-soy beans separately for an appropriate amount of time so they are also well cooked. While the beans are cooking cook the amaranth seed and wakame seaweed flakes in a separate pot until cooked but not mushy, set aside.

After the beans are cooked, drain the beans through a colander over a bowl and reserve some of this hot bean cooking fluid. Pour a little of this hot liquid over your measured amount of salt, stir to dissolve and set aside. Next, mash the beans (I used a potato masher and my hand/fists but one could also use a food grinding device such as those machines typically used for making ground meat for easier processing of the beans).

I chose to only partially mash my beans so that I would still have some discernible pieces of beans in the finished paste for a more rustic end product but you can totally mash them if you prefer that, what is really important at this stage is that they are cooked and pliable enough to be pressed/thrown into the fermentation vessel so that all air bubbles can be excluded from the bean mash. After your cooked beans have been mashed to your preferred constancy, mix in the cooked amaranth seed and seaweed. Once fully combined and evenly mixed in with the beans assess the temperature of the mixture. You cannot mix in the Koji and ‘seeding miso’ (little bit of mature miso from a previous/store-bought batch for inoculating the good bacteria) until the mixture has gone below an internal temperature of 140F/60C. If you do not have a thermometer basically only add the beans once it is comfortable for you to touch the mixture to the back of your hand. If they require cooling before you can mix in the Koji and seed miso, stir the mixture every ten minutes or so to release the heat from the center until the proper temperature is reached.

Once you have mixed the Koji and seed miso into your bean mash and evenly mixed everything check the consistency and add more of the bean cooking fluid as necessary (you are looking for an end consistency that is moist and easily spreadable yet thick enough to hold its shape and not runny). If the Miso paste is warm keep in mind that it will continue to thicken as it cools. Also, the Koji will absorb some of the moisture (especially if it is dry Koji like I used) so if the mixture appears to be too dry at any point, mix in small increments of the bean fluid or clean water at any point.

Once the ingredients are well mixed they need to be packed into a fermentation vessel for aging. You can use any glass or ceramic container (or even a BPA free plastic container if need be) that is cylindrical in shape. This can be a mason jar, a thick-walled flower vase, a 5-gallon food grade plastic bucket or a ceramic fermentation crock specially designed for this purpose. The important thing is that you start with a sterilized fermentation vessel and exclude as many air pockets from the bean mixture as possible when packing it in there (leaving enough space at the top of the vessel for fermentation weights and Tamari to pool (a delicious liquid that forms during fermentation that is the purest form of soya sauce). I prefer to use a fermentation crock that has one of the old water moat airlock lid systems (like those used for making sauerkraut or kimchi) but I have also had good success using 1-liter mason jars. I chose to go about packing the mixture in our crock and jars via the old method of making the bean mash into balls to prevent air pockets and then throwing them into the crock to achieve a form-fitting air pocket minimized end result.

Do not fill the fermentation vessel more than 75% of its capacity as you must leave room for expansion, the weights and the tamari.

Once you have filled up your fermentation vessel(s) with the inoculated bean mash, sprinkle a little bit of sea salt on top evenly to add an extra degree of protection to mitigate unwanted mold growth and ensure a tasty end result.

Add your fermentation weight(s) seal the containers and then place in a dark, dry place at room temperature and wait (we used a dark corner of our kitchen counter as minor seasonal temperature variations are said to impart depth of flavor and result in a more authentic end product). If you are using mason jars or some other container without an air lock system of some type I suggest filling zip lock bags with water and sitting them on top of your fermenting bean mixture to provide a sort of form-fitting weight and sealing system (sealing the top with something like plastic wrap to keep bugs etc out). Also, be sure to intermittently ‘burp’ (release pent up CO-2) your jars if using mason jars with screw top lids as they can explode if the pressure is not released (especially important during the initial stages of fermentation).

Now you just need patience, faith and a positive attitude. Try not to open your jars for at least 3-6 months if at all possible. After at least 6 months unseal your miso and remove any mold that may be growing on top (white mold is not dangerous in this case and the miso underneath is completely safe to eat).

First smell your miso and taste some of the Tamari (fermented bean liquid that collects on top) and then try some of your paste. If you like the flavor as is you can put it into smaller containers in the fridge where it will last for at least a year and enjoy in miso soups and countless other recipes in its young and sweet state) or if you want to develop the flavors to be more unami rich, funky, complex and tangy seal the container back up and allow it to continue aging in a cooler space like a basement or cellar for another 6-12 months. The longer it ages the darker the color, the deeper the flavors, the more bioavailable the nutrients and the higher the levels of antioxidants get.

In Japan, there is a specific variety of longer aged miso called “Hatcho Miso” that is aged for a minimum of 2 years (and up to 5 years) resulting in a very dark, robust and delicious paste that is so high in anti-oxidants and detoxifying compounds it is considered to be a medicinal-grade food product.

We now have some 3 and 4 year miso in our collection as well and the flavor only improves with more time.

If you prefer a smoother end product for making creamier soups and sauces you can process your finished miso paste in a food processor and then pack it into jars (excluding all air) before putting in the fridge to slow the fermentation and preserve a similar flavor to when you put it in there.

Homemade miso paste can be used as a probiotic/protein-rich additive to salad dressings, sandwich spreads, marinades and snack dips. It can also be used to make extremely satisfying miso soup with whatever seasonal veggies/herbs you have on hand from your garden.

Here is an example of one type of hearty Miso Soup I like to make with our homemade paste after it has aged for 2 years minimum. I call it “Midnight Miso”.

The Health Benefits of Miso

Fermentation is where the magic happens, and with regards to Miso, it is what turns grains and beans into a delicious food containing vitamins and minerals and culturing beneficial bacteria that will help nourish the gut and support the immune system.

As stated above, Miso paste can be used to make sauces, spreads and soup stock, or to pickle vegetables.

Its color can vary between white, yellow, red or brown, depending on variety (ingredients and fermentation time influencing the final appearance).

Although miso is traditionally made from soybeans, it can also be made with a wide range of other legumes, grains and vegetable ingredients.

Other ingredients may also be used to make it, including rice, barley, rye, buckwheat, chickpeas, black beans, millet, amaranth, hemp seeds and a wide range of vegetables/spices, all of which affect the color, nutrition and flavor of the final product.

Miso soup contains diverse micronutrients, from the enzymes and probiotics (already mentioned above) to a host of vitamins and minerals.

Miso contains:

-Vitamin A

-B vitamins — vitamin B12, pantothenic acid (B5), niacin (B3), thiamin, riboflavin, B6, and folate

-Vitamin K

-Choline

-Calcium

-Manganese

-Potassium

-Copper

-Zinc

Miso also contains phytochemical antioxidants, which can increase in quantity the longer the fermentation time (at least four months). Antioxidants gobble up free radicals in the body, which create disease, signs of aging, cell death, and even cancer (cell mutation).

Here are some of the many health benefits that miso offers – it certainly packs a powerful nutritional punch!

1. Building strong bones

Miso is a great natural source of vitamin K2, which helps calcium to be stored in our bones. Now, you may think you get plenty of vitamin K from green vegetables, but they contain vitamin K1, which is not thought to be as effective for this purpose – although it does have other important roles. Miso also provides the minerals manganese and phosphorus, which support bone strength too.

2. Good for Your Gut

Unpasteurised miso in particular can be great for our digestive health. It’s a natural source of friendly bacteria, which play many vital roles in gut health, including breaking down and absorbing nutrients and helping to keep the ‘bad’ bugs at bay. For the greatest benefits, make sure you go for unpasteurized miso, as the pasteurized versions are heat-treated and will contain only minimal – if any – beneficial bacteria. And if you’re using unpasteurized, don’t heat your miso to high temperatures, for the same reason; add it to sauces or cooked foods at the end of cooking, or use it in dressings, dips or spreads. A. oryzae is the main probiotic strain found in miso. Research shows that the probiotics in this condiment may help reduce symptoms linked to digestive problems including inflammatory bowel disease (IBD). In addition, the fermentation process also helps improve digestion by reducing the amount of antinutrients in soybeans. Antinutrients are compounds naturally found in foods, including in the soybeans and grains used to produce miso. If you consume antinutrients, they can bind to nutrients in your gut, reducing your body’s ability to absorb them.

Fermentation reduces antinutrient levels in miso and other fermented products, which helps improve digestion.

3. Optimizes The Function Of The Innate Immune System

We’ve seen that unpasteurised miso – that contains natural ‘friendly’ bacteria – may support our gut and digestion. But our immune system may benefit from this effect too. This is because there are lots of immune cells and tissues found in and around the gut. The friendly bacteria in the gut are thought to help ‘train’ these immune cells to recognise which substances are safe and which are unsafe, and respond appropriately. The probiotics in miso help strengthen your gut flora, in turn boosting immunity and reducing the growth of harmful bacteria.

Moreover, a probiotic-rich diet help reduce your risk of being sick and help you recover faster from infections, such as the common cold. Miso contains nutrients help your immune system function optimally (being a good source of zinc and copper, which play important roles in immunity.)

4. A Source of Protein for Vegans & Vegetarians

Miso can be a helpful source of protein – especially for vegans and vegetarians, who may be more likely to fall short in this nutrient. It’s worth noting that the protein in fermented forms of soya beans – such as that found in miso – can be more easily digested than unfermented forms such as tofu and other beans and pulses. So miso is worth including in your diet even if you feel you get lots of protein from these other sources.

5. Hormone Balancing

The natural phytoestrogens found in soya foods may be beneficial for women’s health and hormone balance – especially from around the time of menopause onwards. The greatest benefits are linked with eating traditional fermented forms of soya such as miso – as Japanese women do – rather than unfermented forms such as tofu or soya milk.

6. Energy

Miso provides energy-supporting B vitamins, manganese, copper and phosphorus. All of these nutrients play a role in converting the food we eat into energy.

7. Heart Health

The Vitamin K2 in miso is not only good for our bones, the same nutrient is helpful for our heart and blood vessels too. While it helps calcium to be stored in bones, it helps to prevent calcium being stored in the arteries where it could cause hardening and stiffening, helping to keep them flexible. Vitamin K1 as found in vegetables may not be as useful for this purpose as the vitamin K2 in miso.

8. Memory & Brain Health

Among the many nutrients in miso are B vitamins, zinc and copper. These all play various roles for the nervous system and brain. Miso also contains a nutrient called choline. Choline is not only vital for the nerve cells that make up our brain; it also helps to make a neurotransmitter called acetylcholine, which is vital for storing new memories. Also, probiotic-rich foods such as miso may benefit brain health by helping improve memory and reducing symptoms of anxiety, stress, depression, autism and obsessive-compulsive disorder (OCD).

9. Healthy Hair

Miso is rich in two important nutrients for our hair: zinc and copper. Zinc is essential for healthy hair growth and hair condition, and copper is one of the most important nutrients to maintain hair follicle integrity and pigmentation.

Miso is a particularly good source of the minerals copper and manganese. Both have a role in our antioxidant defenses, including helping to make one of our body’s most important antioxidants, called superoxide dismutase. For this reason, these nutrients help protect against disease and could promote graceful aging.

11. Offers protection from certain types of cancer.

The first may be stomach cancer. Observational studies have repeatedly found a link between high-salt diets and stomach cancer. However, despite its high salt content, miso doesn’t appear to increase the risk of stomach cancer the way other high-salt foods do. For instance, one study compared miso to salt-containing foods such as salted fish, processed meats and pickled foods. The fish, meat and heat processed pickled foods were linked to a 24–27% higher risk of stomach cancer, whereas miso wasn’t linked to any increased risk. Experts believe this may be due to beneficial compounds found in soy, which potentially counter the cancer-promoting effects of salt.

Animal studies also report that eating miso may reduce the risk of lung, colon, stomach and breast cancers. This seems especially true for varieties that are fermented for 180 days or longer.

Miso fermentation can last anywhere from a few weeks to as long as three years. Generally speaking, longer fermentation times produce darker, stronger-tasting miso.

In humans, studies report that regular miso consumption may reduce the risk of liver and breast cancer by 50–54%. The breast-cancer protection appears especially beneficial for postmenopausal women.

As mentioned above, this condiment is also rich in antioxidants, which may help guard your body’s cells against damage from free radicals, a type of cell damage linked to cancer.

I hope this inspires some of you intrepid food fermenters out there to give making your own miso paste a try. It is a process that requires patience and faith but offers rich potential for creative expression and extending the shelf life, flavor, health benefits and bioavailability of some of your favorite garden crops.

May this process of transforming common legumes and grains via teaming up with ancient organisms bring you confidence and joy in the knowing you can transform your seasonal abundances of local legumes into a delicious highly bioavailable gourmet (medicinal quality) preserve with a unique ‘terroir’ that can last years if need be. Happy Fermenting!

Japan’s Edo Period and Regenerative Food Systems

As I mentioned above, I ended up studying a specific period in ancient Japan as part of the research for my book in my pursuit to find historical examples where regenerative agricultural practices were applied as part of the fabric of a culture.

During the Edo period (CE 1603–1868) in Japan centuries of extractive agricultural practices led to degradation of soil structure and soil life, when combined with deforestation this led to the people of Japan realizing they would need to give back to the soil if they wanted to prevent the collapse of their civilization. This led to a time where strict guidelines were implemented to enforce (and incentivize) moving in the direction of a less destructive (and sometimes regenerative) agricultural infrastructure (and society as a whole). It involved key features such as encouraging biodiversity and close-looped material cycle being intertwined under a robust civil infrastructure.

During most of the Edo Period, Japan was closed off to the world and had virtually no exchange with other countries. For the most part (from what I have read), it was a peaceful and self-sufficient period, with almost no war inside the country, and marked a remarkable time of development in the economy and culture of Japan.

Many experts assert that the seeds for the key features of regenerative society were firmly planted in Japan in the Edo period (CE 1603–1868) and can be revived today if we apply the same wisdom which was applied in ancient Japan.

I would contend that punitive measures being applied by top town governmental systems (regardless of what ideological wrappings they have) are not effective long term solutions as threatening someone to behave how you want them to only remains effective as long as the threat and ability to act on the threat does, and even then industrious and inventive people will wind a way to circumvent said punitive measures if they really want to.

That being said, I do think it is worth pointing out that, unlike the “One Health”, Rockefellar Foundation and WEF’s puppets (such as Trudeau) and their claims of wanting to support regenerative agriculture, their 2030 agenda, their “sustainable development goals”, “carbon taxes” and “nitrogen restrictions” for farmers etc, the will to impose strict rules on how people interact with the farm land and where their waste products end up during the Edo Period in Japan appears (to me) to have arisen out of a genuine necessity and want to salvage (and sometimes regenerate) the landscape that had been decimated by degenerative/extractive agricultural practices and urban development.

Incentivizing behavior that helps to regenerate the landscape is at least a step in the right direction, as perhaps after being bribed to do something for long enough by the government the people doing it will begin to see the long term intrinsic benefits offered to their own lives by engaging in said actions.

Though, as much as I think the Edo Period is a fascinating time to analyze and speculate about what it would look like for the policies of that period in Japan to be implemented in present day, in the end I feel that the most permanent and systemic change cannot and will not be brought about via any top down policies (whether they are punitive or incentivizing) but rather must originate from within.

The societal changes that set down roots and persist through the millennia begin with grass roots movements of individuals applying concepts and ways of living in a decentralized fashion. These are the seeds planted by individuals that are living and embodying the change they want to see in the world, embracing radical authenticity and starting fractal chain reactions in our collective that spread outwardly in all directions.

In essence, it is the seed that rises from within that is born from living the way one wants the world to be, which readily self sows and sets down roots far and wide. Individuals embodying the intrinsic abundance, purpose and joy that results from living with integrity, compassion, courage and generosity provides an incentive more enticing than any government bribe for others to follow suit. They show other people a way of living that heals the broken parts within us, heals the land around us, begins to bind our shattered communities together again and offers True Wealth.

This brings me to another practice from the Edo era in Japan which I have written about and feel can offer us some practical and philosophical insight on how we might begin the process of regeneration (both of the landscape within, the physical landscape of our biosphere and the societal landscape as well) and that practice is the art of Kintsugi.

While it is true that many of our communities (as well as much of our dominant western culture and broader societal infrastructure) is broken, this does not mean we should give up or lose hope. We can find wisdom and paths to healing through closely observing the Japanese art of Kintsugi.

Whether we are talking about merging the broken shards of a community or the intimate relationships our ancestors had with the land and their food, fermentation is a great method to engage in that process. Fermenting food allows one to connect with our ancestors in a tangible way through using their tried and true methods to preserve, augment and enhance the flavors of our garden crops and help us preserve them in a low tech method (enhancing our emergency preparedness while also giving us the satisfying knowing that we are engaging in a process that was honed by those that walked before us on this Earth with humility, curiosity and ingenuity).

Fermenting food also gives us a way to heal our mindstate and the broken worldviews that have become dominant in communities and our broader society with regards to bacteria. In recent years we have seen much fear mongering about microbes pushed forward by NGO-s, philanthropaths, transnational corporations and their puppets in governments all over the world but being afraid of microbes is not only irrational, it is directly counter intuitive to human health. We depend on microbes to survive and thrive, thus, consciously choosing to cultivate beneficial microbes, to engage with and learn about them (through the act of fermenting food) is sort of like signing a peace treaty with the bacterial kingdom and taking steps to heal our broken relationship with our ancient allies in the microbial kingdoms.

“The problem with killing 99.9 percent of bacteria is that most of them protect us from the few that can make us sick.

Given the 'War on Bacteria' so culturally prominent in our time, the well-being of our microbial ecology requires regular replenishment and diversification now more than ever.

Wild foods, microbial cultures included, possess a great, unmediated life force, which can help us adapt to shifting conditions and lower our susceptibility to disease. These microorganisms are everywhere, and the techniques for fermenting with them are simple and flexible.

To ferment your own food is to lodge an eloquent protest--of the senses--against the homogenization of flavors and food experiences now rolling like a great, undifferentiated lawn across the globe. It Is also a declaration of independence from an economy that would much prefer we were all passive consumers of its commodities, rather than creators of unique products expressive of ourselves and the places where we live.

Resistance takes place on many planes. Occasionally it can be dramatic and public, but most of the decisions we are faced with are mundane and private. What to eat is a choice that we make several times a day, if we are lucky. The cumulative choices we make about food have profound implications. Food offers us many opportunities to resist the culture of mass marketing and commodification. Though consumer action can take many creative and powerful forms, we do not have to be reduced to the role of consumers selecting from seductive convenience items. We can merge appetite with activism and choose to involve ourselves in food as co-creators.”

― Sandor Ellix Katz (Author of "The Art of Fermentation" )

When you cultivate food in the garden in a way that gives back to the living Earth and honors the many gifts we have been given in this life, you are engaging in a sort of Spiritual Reciprocity by creating nourishing foods with those crops in the kitchen. Using your hands to give back to the Earth and to give thanks to Creator for the gift you have been given in this human body, by taking good care of it with nourishing, delicious and vibrant meals (that use food as medicine and provide poetry for the soul) is a way to give back to your body, your temple and thus a way to give back and say thank you to Creator.

One of the most powerful choices we can make to heal the relationship to Mother Earth, give back to and honor our sacred temple and in doing so engage in an act of Reciprocity begins with a handful of seeds and some TLC.

I am wishing you all a spring time filled with hope, peace, feeling nourished and inspired by the abundance you cultivate and create in the garden and in the kitchen.

Thanks, Gavin. Not sure if you mentioned it, but everyone should be aware that the fermented pastes need to be added after the stove is off b/c you don't want to pasteurize the living probiotic bacteria. It's crazy yoghurt is sold with sugars and with most of the fat taken out, pasteurized, defeating the purpose.

When I grew up in Seoul, we had huge earthen jars, sometimes buried in the ground with kimchee, denjang, kkochujang, anchovy paste, etc.

With more and more people becoming self-sufficient, fermented pastes and fermented foods in general will become bigger with all that extra food from our gardens.

Dear Gavin,

although I sometimes feel to lazy to read your long articles in one shot, when I do, I am rewarded with the talent of one of the best spiritual food writers of our era: You.

I know you work hard on everything you do and wanted to let you know it’s greatly appreciated!

I wish I could write as well and as passionately as you about food and it’s implications beyond the physical for humanity.

You are doing your part and more, in building this future we all crave.

Much love brother,

Alain