Day Eleven: LAMB'S QUARTERS (aka “Fat Hen”)

Its ubiquitous, nutritious, self-perpetuating, quickly regenerates and its free! Learning to harvest and eat this plant is a wise choice for any looking to increase their emergency preparedness

It also goes by the names wild spinach, White goosefoot, fat hen, and pigweed, but it's not the same pigweed some know as amaranth.

Amaranth's genus is Amaranthus, although both lambsquarters and amaranth are in the same family, Amaranthaceae, so you could say they're cousins.

It's also closely related to quinoa (Chenopodium quinoa).

Every grain we have today has a wild ancestor, but some are more domesticated than others. Quinoa (Chenopodium quinoa) is relatively new to domestication, and its wild cousin (Chenopodium album) is not that different than the modern cultivated grain. The seeds may be a bit smaller, but the plants look almost identical when they sprout in the spring.

What you may not know, however, is that wild quinoa likely grows in your backyard. Also known as goosefoot, it’s almost as common as dandelions, and it’s viewed as a weed by gardeners around the world. Most foragers harvest its leaves as a tasty salad green in the spring, but if you allow the plants to mature, they’ll produce a wild grain crop in the fall.

Some varieties of Lamb’s Quarters have brightly colored leaves and seeds due to the anthocyanin content produced by the plant in response to cold.

Lamb's quarters is a purifying plant that helps to restore healthy nutrients to poor quality soil. This unique, edible plant tends to spread quickly no matter the soil condition. One plant can produce up to 75,000 seeds!

Lamb’s Quarters is considered by some to be another non-native plant that was intentionally introduced as a food crop by European settlers.

Long forgotten as a mainstream food source nowadays, it regularly shows up uninvited in gardens throughout Canada and the United States.

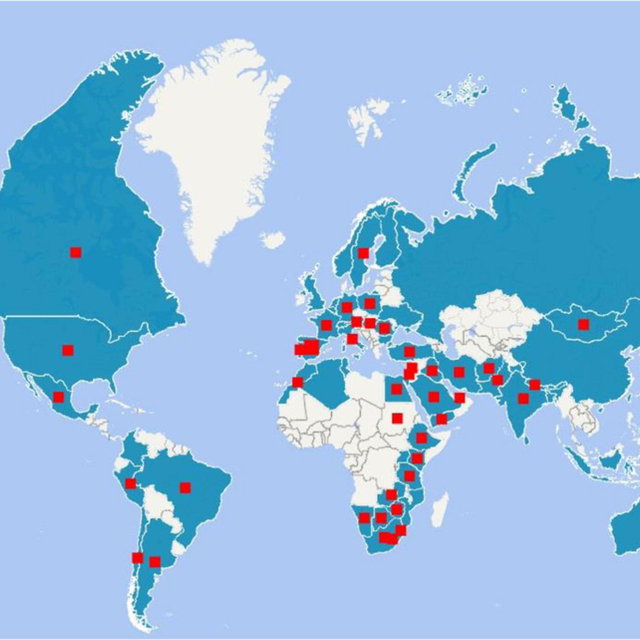

They are remarkably adaptable and can grow in all types of soil and at many pH levels. It is found throughout the world -- everywhere except extreme desert climates, from sea level to as high as 11,000 feet. It is one of the last ‘weeds’ to be killed by frost.

There exist several varieties; the most common being Chenopodium album var. album, which grows all over the United States and much of Canada, and originated from Eurasia. Some varieties, such as Chenopodium album var. missouriense, are considered native to certain areas in the US. Regardless of the variety, they are all edible and choice!

Given how abundant goosefoot plants are, it’s good to know about goosefoot, aka lamb’s quarter or “wild quinao” grain for a survival situation.

Nutrition of Lamb’s Quarter:

As mentioned above, it is known as wild spinach to many, though Lamb’s quarters is even more nutritious than its tame counterpart. It is rich in beta carotene, vitamin B2, niacin, calcium, iron, and phosphorus. Lamb’s quarter greens are also an excellent source of vitamin A and more than 4% protein.

Due to its vitamin A and C content this food helps boost your immune function. It also contains a good amount of fiber which is important for promoting probiotic bacteria in the colon and thus boosting your immune system.

Antioxidants – The fresh shoots of Lambs Quarters also contains a large amount of Beta Carotene which is a powerful antioxidant. Also contains lots of Vitamin A which is a powerful antioxidant and Vitamin C which is great for staving off colds and flues and boosting your immune system… and Vitamin K for clotting.

Magenta Lamb’s Quarter also contains a type of antioxidant called Anthocyanins (a group of compounds that act as antioxidants offering a wide range of health benefits which I wrote about in a past article that you can find here)

Anti-inflammatory – Lambs Quarters is anti-inflammatory making it great for arthritis, joint pain, inflammation, swelling and other diseases that are caused by inflammation including cardiovascular disease and strokes.

Its seeds are high in protein, calcium, vitamin A, potassium, and phosphorous.

History and Cultural significance of the plant:

Known as Praiseach fhiáin to my Celtic ancestors, Bathua in Hindi and koko'cibag to the Potawatomi/Ojibwe peoples of the Great Lakes regions in the Anishinaabemowin language.

Charred and waterlogged seeds of fat-hen are often recorded in archaeological deposits from Viking and medieval towns in Ireland, reflecting a plant that would have been growing and gathered within the town. Fat-hen was sold by street vendors and eaten as a leafy vegetable until as recently as the eighteenth century in Dublin, and it has even been confirmed that fat-hen plants were not just gathered from wild stands, but were actually managed as a food resource since the prehistoric period (Geraghty 1996; Stokes and Rowley-Conwy 2002).

Few plants that we would recognize as modern day vegetables were known in Britain prior to the Roman Invasion of the country. However, Celtic beans (Vicia faba L.) and Lamb’s Quarters (aka Fat hen) were grown and a kind of parsnip was found in Britain at that time.

Fat hen (Chenopodium album) can be used when young as a vegetable like spinach for human consumption; the mature dried plant was treated like hay for winter animal fodder and the seeds were ground up into a flour for bread making.

More than 54,000 seeds of pigweed (Chenopodium album L.) were found in a pot from the Neolithic settlement of Niederwil (Switzerland), as well as in the intestines of seven European Iron Age bog bodies (Behre, 2008).

In Medieval Ireland, there was a huge increase in food trading into and out of Ireland. Imports included exotic foods such as figs and walnuts. However, while cultivated foods were important, wild foods remained a key element of people's diets. Seeds of Chenopodium album L. (fat-hen) are often found at excavations of medieval sites. Now considered a troublesome weed, fat-hen was once a useful food. Its leaves were sold by Dublin street traders until the 18th century as a vegetable, and the seeds can also be eaten, much like its better-known relative, Chenopodium quinoa Willd. (quinoa).

According to Huron H. Smith (published in a report titled “POTAWATOMI MEDICINES”) It is said that “..this plant furnishes a relish food for salads and spring greens when the leaves are used by the Forest Potawatomi..”

There is also evidence that Chenopodium album L. was harvested (and perhaps cultivated by pre-historic communicites of the Blackfoot indigenous peoples (who resided in what is now the Canadian provinces of Alberta, BC and Montana of the United States) and more recent evidence they used this plant as food from the sixteenth century.

“Just as Incan people in the Andes grew Chenopodium quinoa for its nutritious seeds, so Chenopodium album has long been cultivated in India. Napoleon Bonaparte, who always paid close attention to the diet of his troops, employed ground pigweed seeds as a flour supplement for his army’s endless bread. (Source)”

This veggie has been used in the treatment of various ailments for a long period of time. Lamb’s Quarters (known as Bathua in Hindi) is considered as a veggie rich in medicinal properties and is commonly used in Indian and Assamese cuisine for their health benefits.

Lamb’s Quarters In the Kitchen:

LAMB'S QUARTERS SALAD : https://foragerchef.com/lambs-quarters-salad/

Lamb's Quarters Frittata : https://www.thetarttart.com/recipes/breakfast/lambs-quarters-frittata/?fbclid=IwAR1nuqiqqjHTnHsagfYlZauV11xox_M0sisWMh36GHXvwIIHypx5nKDMWhI

You can also sprout the seeds to use in sandwiches, salads wraps or used in baking recipes

Dumplings made with sprouted lamb’s quarters flour: https://wildfoodgirl.com/2014/seed-sprouting-with-quinoas-wild-kin/?fbclid=IwAR1e9Ob0qPFWMzBblXyNl32hQjNLsNQ9B7qxrTy_P2ATzE9cj-8jAAvdQ9Q

Lambs’ Quarters Pesto: https://wildfoodgirl.com/2014/lambs-quarters-pesto-sunflower-seeds/?fbclid=IwAR18ACDH0bvfS7_nHkSnQA3W6aUyUCAtyKwCLrl48hZgMuIJi4YuItgWjLg

Lamb’s Quarters Pesto, Sun Dried Tomatoes, and Black Olives, Lamb’s Quarters greens and feta over Whole Wheat Fusilli:

Wild Pesto Pasta Featuring Lamb's Quarters, Garlic Mustard, And Sautéed Field Garlic Bulbs : The base was toasted pistachios pine nuts nutritional yeast lemon juice and olive oil tossed with noodles. Studded within are blanched fiddle head ferns from the market.

Cream of Lambsquarter Soup : https://www.pbs.org/food/recipes/cream-of-lambsquarter-soup/?fbclid=IwAR2FP2qxuQiBTeJNmjsYGhfaTW2sp6veoTN1Pfn6yD5G1diugyxcV9gRuPA

Lambsquarters Triangles : https://alongthegrapevine.wordpress.com/2014/05/30/lambsquarters-triangles/?fbclid=IwAR1yYWtwa1A83G1E7tFZcNdb8eDlHnkTckVKCtEEfCHMA_ptw0ZBJ347BnM

WILD SPINACH CAKE : https://foragerchef.com/wild-spinach-cake/

If you like Indian food here is a link to where you can explore 477 Indian recipes that incorporate Lamb’s Qaurters: https://cookpad.com/in/search/bathua

FORAGING WILD QUINOA (GOOSEFOOT SEED) : https://practicalselfreliance.com/chenopodium-album-grain/

Habitat of the herb:

It is often one of the first weeds to appear on newly cultivated soils (which were cultivated via heavy tilling). This is due to the fact that as with many other opportunistic plants deemed as “weeds” in the western world, these plants are often showing up in great numbers in an attempt to heal the damage humans have done to the living Earth.

Lamb’s quarter thrives as a common ’weed’ in gardens, near streams, rivers, forest clearings, fields, waste places, and disturbed soils. It is very hardy and grows in many areas throughout Canada and the U.S. It is also found in South America, Central America, many countries throughout Africa, the Middle East, Europe, several Asian countries (very common in India), Australia and New Zealand.

Be aware that lambsquarter leaves contain oxalic acid, which is a concern for anyone who should limit oxalates or wants to avoid them.

They can be eaten raw or cooked but cooking reduces the oxalate content somewhat.

Cooking won't get rid of heavy metals, nitrates or other toxins, though, so I'll reiterate the importance of always foraging for wild food where the soil hasn't been contaminated by fertilizer and pesticides.

Since the leaves are so tender and don't keep long, they're best picked right before you plan to eat them.

And if you're going to eat them raw, you may want to rinse off the mealy coating from the leaves first.

The mealy powder is perfectly edible, but it gives the leaves a less-than-desirable grittiness.

If you plan to cook them, be sure to gather more than you think you'll need since they're really prone to cooking down to nothing and turning to mush.

The best method of cooking is to lightly steam or sautee to avoid overcooking.

You can also dry the leaves and use them later in soups and stews.

Edible parts of Lamb's Quarters:

Leaves - raw (in moderation) or cooked. A very acceptable spinach substitute, the taste is a little bland but this can be improved by adding a few stronger-flavored leaves. The leaves are best not eaten raw, see the notes below on anti-nutrient content. The leaves are generally very nutritious but very large quantities can disturb the nervous system and cause gastric pain. The leaves contain about 3.9% protein, 0.76% fat, 8.93% carbohydrate, 3% ash.

Edible seed - dried and ground into a meal and eaten raw or baked into a bread. The seed can also be sprouted and added to salads. The seed is very fiddly to harvest and use due to its small size. Although it is rather small, we have found the seed very easy to harvest and simple enough to utilize. The seed should be soaked in water overnight (or fully sprouted) and thoroughly rinsed before being used in order to remove any saponins.

Young inflorescences - cooked. A tasty broccoli substitute.

Anti-nutrient content: As mentioned above it does contain some oxalic acid so it is better cook this plant before eating, but some people do use Lambs Quarters in their salads.

The greens can be eaten raw, steamed, or sautéed or added to soups and stews. If you dislike the texture of raw spinach, or it gives you a funny feeling in your mouth, you probably won’t enjoy raw lamb’s quarters.

I enjoy the steamed greens in lasagna, omelets, quiche, and cold pasta salads. The sky’s the limit with this pleasant green—you can substitute it in most any dish that calls for spinach or Swiss chard. To preserve any surplus bounty, you can blanch and freeze the greens, or freeze a batch of pesto or pâté.

Dietary oxalates are found in a wide range of cultivated and wild foods, including spinach (Spinacia oleracea), Swiss chard (Beta vulgaris subsp. vulgaris), beet leaves (Beta vulgaris), black tea (Camellia sinensis), rhubarb (Rheum rhabarbarum), garden sorrel (Rumex acestosa), sheep sorrel (Rumex acestosella), purslane (Portulaca oleracea), chickweed (Stellaria media), yellow dock (Rumex crispus, R. obtusifolius), and lamb’s quarters.

You’ll often see precautions in wild foods literature against ingesting high quantities of plants that are rich in oxalates or oxalic acid (the same molecules). There are two primary concerns: reduced mineral uptake and increased kidney stone formation.

Oxalates (which are acidic) bind to minerals (including calcium, magnesium, and iron) in the digestive tract, thereby rendering the minerals unavailable for assimilation. However, many leafy greens containing oxalates also contain considerable levels of minerals. When we eat a variety of greens and other mineral-rich foods in our diet, this doesn’t appear to be much of an issue.

An additional factor is a plant’s calcium levels. Calcium binds to oxalic acid, rendering it nonabsorbable (it isn’t absorbed into the bloodstream and, instead, passes through the feces). Therefore, it’s important to consider the relative proportion of oxalates to calcium.

Be mindful of where you are harvesting lamb’s quarters from. Because it is so susceptible to absorbing what’s around it – whether good or bad – it’s best to avoid harvesting lamb’s quarters from areas that may be contaminated.

Distinguishing Features:

Annual plant that looks dusty from a distance due to a white coating on the leaves, and when moist, water simply beads and runs off. It produces tiny green flowers that form in clusters on top of spikes, and the leaves resemble the shape of a goosefoot.

Beginning in late spring, lamb's quarters sends up shoots and tender leaves. When first appearing, the leaves are opposite, triangular- to oval-shaped, and covered with a whitish mealy coating. The leaf margins may be coarsely toothed, wavy, or smooth. As the plant matures, the leaves become alternate, and often more triangular- or diamond-shaped. The leaf margin is typically coarsely toothed. The underside of the leaf and the new growth at the top of the plant retain the whitish dusting. Petioles (leaf stems) and stalks are often tinged with purple.

When lamb's quarters goes to flower, it has reached its full height. If growing in ideal conditions, the plant can reach heights of up to six feet. More typically they grow from two to three feet tall. The flower is inconspicuous: small, roundish or oval, light green in color, and growing in clusters at the top of the stalk. Leaves at the top of the stalk are typically smaller, lance-shaped, and with little-to-no serration.

Come fall the flowerheads become brown and papery, and develop seeds on the inside. When mature, the seeds are black to brown, shiny, and somewhat flattened. However, you will need to rub off the chaff to see the actual seed.

Lamb's quarters is part of the goosefoot family, which has been reclassified as a subfamily of the amaranth family. Some plants in this family look very similar, but most of them are edible. Edible look-alikes include certain amaranth species (Amaranthus spp.) and orache species (Atriplex spp.). Also edible, but not in the goosefoot family, is black nightshade (Solanum nigrum). (Black nightshade is often miscategorized as poisonous. It is edible, but does require more caution than lamb's quarters. I would recommend staying clear of the greens unless you're an experienced forager.)

The only poisonous look-alike I can think of is belladona (Atropa belladonna), but in my opinion it doesn't look much like lamb's quarters at all; even a basic understanding of lamb's quarters' characteristics will prevent confusion between the two.

Black nightshade bears only a faint resemblance to lamb's quarters. The leaves are generally egg-shaped, with smooth or wavy margins. Some leaves may be sparsely toothed, but they are not as consistently toothed as lamb's quarters' leaves. Furthermore, the petioles (leaf stems) of black nightshade are "winged," meaning that a narrow bit of leaf runs all the way down the stem. The flowers differ vastly from those of lamb's quarters, being 5-petaled, white or violet, much larger at 1/4" to 1/3" across, and growing in small clusters along the stem.

Belladonna (also called deadly nightshade) is a European native with limited range in the US. I've never personally seen it, but as a potentially deadly plant, it's good practice to familiarize yourself. It bears much closer resemblance to black nightshade than lamb's quarters. The leaves are oval and untoothed. The flowers grow singly from the axils of upper leaves (where the petiole meets the stalk.) They are brownish purple in color, with five fused petals. The berries are also single, initially green and black when fully ripe, and surrounded by a star-shaped calyx (modified leaves) that extends far beyond the fruit itself.

Side note for the garden:

Some organic farmers use lambsquarter as a companion plant in their gardens because they believe lambsquarter attracts leaf miners, Japanese beetles and aphids away from the more desirable plants.

For more information on Lamb’s Quarters:

https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fphar.2020.00105/full

https://worldwidescience.org/topicpages/g/goosefoot+chenopodium+album.html

https://www.roman-britain.co.uk/the-celts-and-celtic-life/farming-in-celtic-britain/

http://ancientfoodandfarming.blogspot.com/2013/10/archaeological-evidence-for-consumption.html

http://butser.org.uk/Food%20of%20the%20Prehistoric%20Celts.pdf

https://gobotany.nativeplanttrust.org/species/chenopodium/album/

https://www.bimbima.com/ayurveda/health-benefits-of-bathua-chenopodium-album/335/

https://foragerchef.com/lambs-quarters-wild-spinach/

I hope you found this information helpful and will try foraging for some Lamb’s Quarters and find peace of mind in the knowing that you are surrounded in food and medicine.

If we learn from Mother Nature and accept her open hand we can thrive and nurture our bodies in any and all situations (while staying guided by integrity and love).

We can align our wealth and health with the health and wealth of the living Earth and through merging with her regenerative capacity and inherent abundance we can become irrepressible.

We can lift ourselves and our communities out of the widespread modern day ‘poverty of plant knowledge’ and in doing so become resilient enough to survive and thrive no matter what life throws our way.

We are the ones we have been waiting for.

Good morning, Gavin! When I lived in the city I used to buy Lamb's Quarter at the farmer's market. Last summer, it popped up in my garden alongside Amaranth - neither of them planted by me. This year I'll probably just have a wait and see what shows up experience in the area where I had intended to have a vegetable garden.

When you mentioned pesticides/contaminated areas, my mind couldn't help but go to what I feel is one of the greatest threats to our health today - climate geoengineering. I don't use pesticides or herbicides and everything planted here is organic, but I can't control what is raining down from our skies. I try hard not to obsess over it but it does weigh heavily on my mind. I'm betting Mullein will be one of your featured "weeds" and I have a story about that to share.

Thanks for another great article. I'm kind of a lazy no-frills cook, but I do make most of my own food. I at least love looking at the yummy food photos! :) Those Triangles look so good! 🌿

Argh, I just composted all these 'weeds' that were 'invading' my raised beds! Ah well, we live and learn! Thank you for these articles; I found out lots of new stuff this week and enjoy sharing my new-found knowledge with my Permaculture Club. I also love the references to what our ancestors did with these plants, especially the Celts, who I've reconnected to recently.