Schisandra chinensis (aka "five flavor fruit")

Exploring the many gifts offered by Schisandra the in the context of Food Forest Design. This is Installment #5 of the Stacking Functions in the Garden, Food Forest and Medicine Cabinet series.

Schisandra chinensis (aka "five flavor fruit" or “Wu Wei Zi”

Family: Schisandraceae

Part used for medicine/food: fruit, leaves, shoots, roots and vine wood.

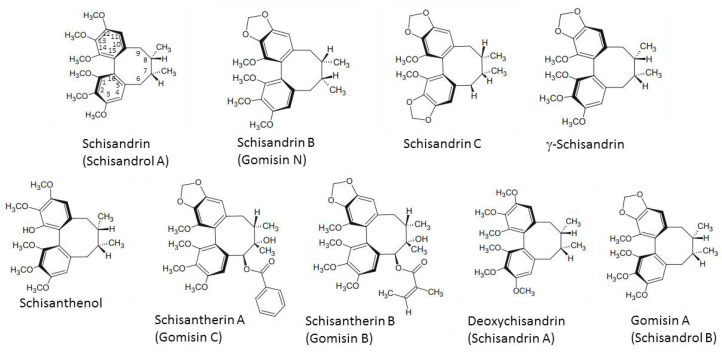

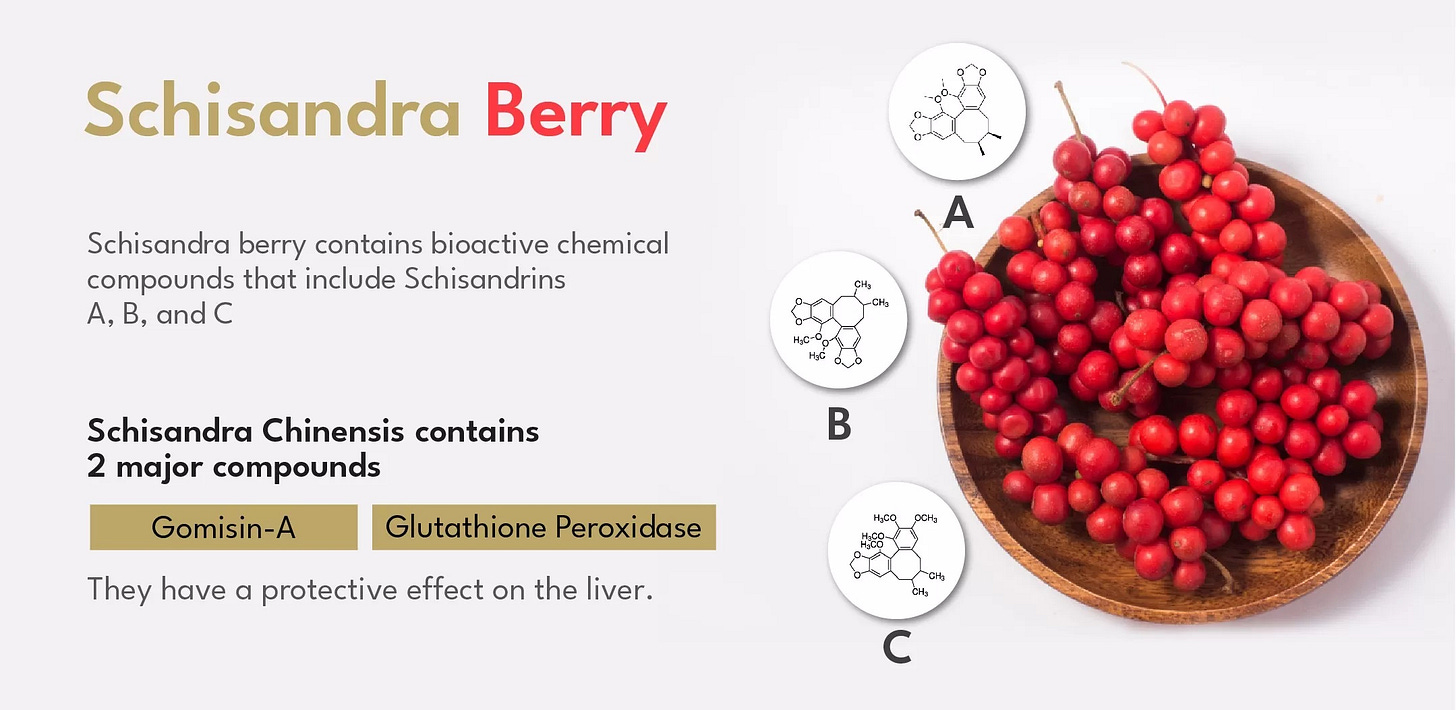

Constituents:

Lignans (schizadrin, gomisin, deoxyschizandrin and pregomisin), phytosterols (beta-sitosterols, stigmasterol), volatile/essential oils (α-Bergamotene, β-chamigrene, β-himachalene, and ylangene), nutrients (Vit A, C, E), phenolic acids (namely chlorogenic, cryptochlorogenic, gallic, neochromogenic, protocatalytic, salicylic, syringic and vanillic acids), flavonoids (quercetin, isoquercitrin, rutin, and hyperoside), tannins (hydrolysable, e.g., gallic acid esters, and condensed, e.g., proanthocyanidins and catechol-type tannins), triterpenoids (lanostane and cycloartane-type triterpenoids and nortiterpenoids), organic acids (citric, fumaric, malic, and tartaric acids), polysaccharides (mainly glucose, galactose, mannose, and rhamnose in various molar proportions), kaempferol, anthocyanins and bioelements (minerals) Cr, Cu, Co, Ca, Mg, Fe, Zn, Mn, B, Ni,) [1,7,9]. Fruits contain substantial amounts of minerals. 100 g of dried fruits contains Fe, Mn, Cu, K, and Mg in amounts that cover 96%, 320%, 48%, 54%, and 33% of the Recommended Daily Intake (RDI).

Medicinal actions:

General tonic/stimulant/restorative, nervous system tonic, mild anti-depressant, anti-stress, adaptogen, adrenal tonic, regulator of blood glucose & mucosal secretions, antioxidant, astringent, anti-tussive, lung tonic, regulates blood pressure, anti-cholesterol, hepatoprotective, oxytocic, anti-allergen, anti-anxiety agent, improves memory, cognitive function, anti-aging, anticancer, irritation-soothing, suppresses platelet aggregation, cardioprotective, tumor suppressor, wound-healing and corrects metabolic imbalances.

Medical uses:

S. chinensis is widely used as an herbal supplement in traditional Chinese medicine and in Western phytotherapy [1,2,4,5], whereas in Russia—as a potent adaptogen, improving disease and stress tolerance, and increasing energy, endurance, and physical performance [2,3].

Used as a general hepatoprotector, antioxidant and adaptogen by increase the nervous reflex response. Promotes vitality and increases memory and cognitive functions while providing resistance to stress. Will tone and strengthen the immune system to increase physical performance and endurance and promotes recovery after surgery. Will enhance athlete’s performance and improve liver detoxification and functions.

Stimulates increased levels of Myelopoiesis (the production of bone marrow and of all cells that arise from it, such as mesenchymal stem cells) and haematopoiesis (the formation of blood cellular components such as haematopoietic stem cells).

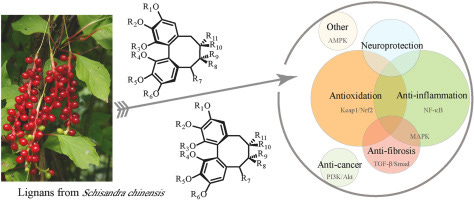

Pharmacology:

Lignans (schizadrin, gomisin, deoxyschizandrin and pregomisin) are hepatoprotective and immunomodulating. Appear to protect the liver by activating liver enzymes that produce glutathione.

Lignans also interfere with platelet activating factor, a chemical that promotes inflammation in a number of conditions.

Pharmacy: Whole berries: 3 grams per day Powder: 250mg TID. Infusion: 2 tsp/cup, TID. Tincture: (1:2, 45%), 5-10ml QD.

Contraindications: Avoid in fever.

Cold Hardiness: 3 - 8

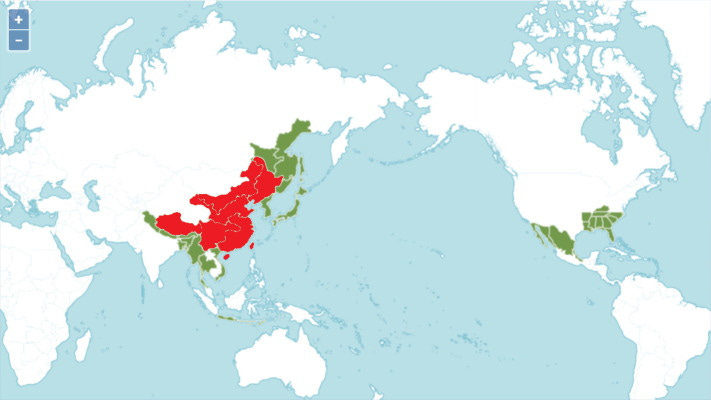

Native/naturalized Range:

GROWTH FORM:

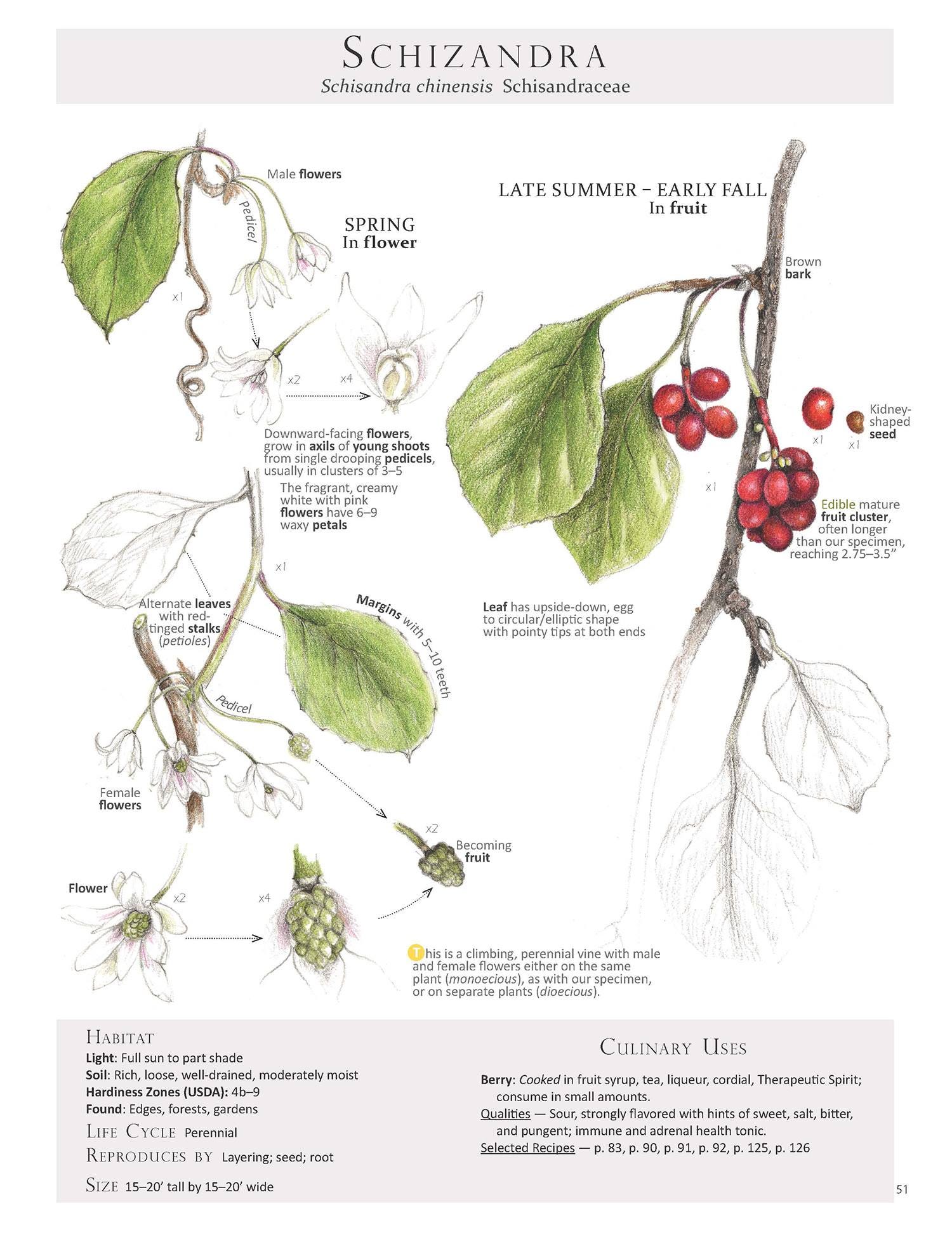

Schisandra chinensis is a deciduous Climber vine growing to 9 m (29ft 6in) at a medium rate.

REPRODUCTION:

The flowers of Schisandra are unisexual and the species itself is dioecious. The plant is therefore not self-fertile, hence flowers on a female plant will only produce fruit when fertilized with pollen from a male plant. The female flowers are white or cream-coloured and turn slightly reddish to the end of the flowering season.[12] They have 5–12 waxy, spirally arranged tepals forming the perianth and 12–120 pistils.[11] The tepals show a transition in colour from green for the outer tepals to more pigmentation for the inner ones.[11] The flowers typically grow out of the leaf axils in clusters, later forming grape clusters with berries, but can also be found solitary.[8][13] The male flower has 5 stamens with filaments of different lengths[11][13] The flowers of S. chinensis are important for various pollinators such as bees, beetles and small moths.[8]

Seed:

The seeds of S. chinensis of local reproduction are kidney-shaped with a smooth, shiny surface and rough peel. Seed peel usually has many layers: external epidermis, adjoining 4–6 rows of highly lignified stony cells of the sclerenchyma, under which the inner layer of the seed coat is located, consisting of parenchymatic thin-walled tissue. The main seed volume is occupied by dense endosperm, containing polyhedral cells with fatty oil drops and very small aleurone cells 8–15 μm in diameter. The embryo is heart-shaped, slightly differentiated (0.3–0.6 cm in length, diameter does not exceed 0.2 cm). The embryo is located at the narrow part of the seed.

The seeds have the capacity to stay dormant and to form soil seed banks. Distribution of seeds mainly occurs through birds.[8]

Habitat and Ecological Niche:

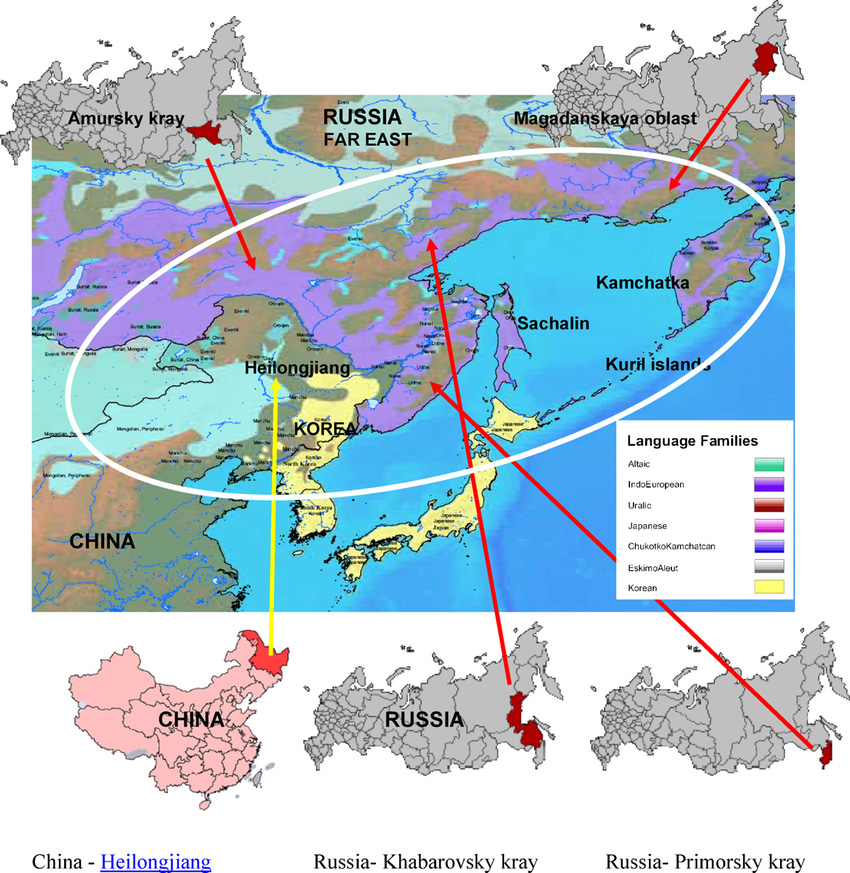

This vining plant is native to forests of Northern China, the Russian Far East and Korea. Wild varieties are also found in Japan.

Schisandra glabra, the bay star-vine, is the only American species of this primarily Asian genus. It is native to the southeastern United States and northern Mexico. It grows in Louisiana, eastern Arkansas, southwestern Tennessee, Mississippi, Alabama, northwestern Florida, and Georgia, with isolated populations in Kentucky, South Carolina, North Carolina, and Hidalgo.[3][5][6] Despite its wide range, it is considered a vulnerable species. Few populations are secure due to competition from invasive species (such as Japanese honeysuckle) and habitat loss.

It is usually found in Mixed forests, especially on the margins, also by streams and brooks, usually on sandy soils[74].

The plant can grow in wet environments and tolerates cold temperatures to −30 °C. Its optimal growing temperature is at 20–25 °C. Schisandra grows in acidic (pH of 6.5 – 6.8), deep and loose sandy loam soils.[15] Furthermore, Schisandra cannot withstand dense and compact soils and prefers soils rich in humus.[16] The plant grows in shade with moist, well-drained soil.

Alternative Names/Names in Other Languages:

Schisandra | Schizandra

Magnolia Berry

Five-Flavor-Fruit

Limonnik (Russian)

Wu wei zi

Five flavor berry

Gomishi

Omicha

Omija

Ngu mie gee

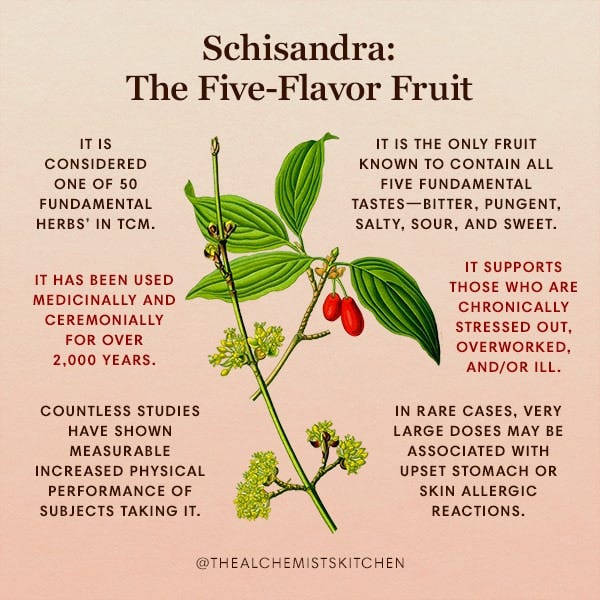

Etymology

Schisandra berry’s Chinese name, wǔ wèi zi, means “five flavor fruit.” It earned this name because it’s the only fruit known to contain all five fundamental tastes—bitter, pungent, salty, sour, and sweet. According to TCM theory, this unique composition supports the 5 zang organs, or the liver, kidneys, heart, lungs, and spleen. This cooperative of zang organs produce and store qi, the vital energy or life force that flows through all living things.5

The western botanical name, Schisandra, comes from the genus Schisandraceae, which was named by French botanist André Michaux in his “Flora Boreali-Americana,” published in 1803. Sometimes it is incorrectly spelled Schizandra, which is a misunderstanding of origin. According to the American Herbal Pharmacopeia, “[The name Schisandra] is derived from the ancient Greek schisis meaning “crevice” or “fissure”. Many writers have incorrectly written this as Schizandra presumably from the Greek schizo meaning “split” or “separate” which has resulted in inconsistencies in the literature. This is further confused as “Manual of Cultivated Trees” [published in] 1954 reported that the name Schisandra was in fact based on the verb schizo.”1

History

Recorded use of Schisandra dates back to the Tang dynasty, first described in China’s first known herbal encyclopedia, “Shen Nong Ben Cao Jing,” or “The Divine Farmer’s Materia Medica,” written and compiled between about 200 and 250 CE.5 It is considered one of 50 Fundamental Herbs’ in TCM. Chinese, Korean, and Russian cultures have used its berries in a number of ways; in beauty tonic blends, as an ingredient in soups and stews, and infused into wines. Awareness of it reached the European and American countries relatively recently; the first monograph on it can be found in The American Pharmacopoeia from 1999.1 Nowadays, despite its presence in the current pharmacopoeial documents, Schisandra and its myriad offerings are still largely unknown.

Medicinal Benefits

Schisandra (Schisandra chinensis) holds a special place in history since it was used along with other ancient herbs, like ginseng, goji berry and reishi, by Taoist masters, Chinese emperors and elitists. In Russia, schisandra first gained recognition as an “adaptogen agent” in the 1960s when it was published in the official medicine of the USSR handbook, following the discovery that it helps fight adrenal fatigue, heart problems and the negative effects of stress.

Interestingly, schisandra gets its name due to the berries having quite a complex taste, since they hold five distinct flavor properties: bitter, sweet, sour, salty and hot. This is why schisdanra is sometimes called “the five-flavored berry.”

Beyond just how it tastes, its flavor components are important for understanding the way it works. The secret to schisandra’s power is that it’s said to have properties pertaining to all five elements in Traditional Chinese Medicine (TCM), which means it works in multiple “meridians” within the body to restore internal balance and health.

Because it impacts nearly every organ system within the human body (what TCM refers to as the 12 “meridians”), it has dozens of uses and benefits. TCM views schisandra as an herb that helps balance all three “treasures” within the body: jing, shen and chi.

It’s most well-known for boosting liver function and helping with adrenal functions, but other benefits also include:

acting like a powerful brain tonic (improving focus, concentration, memory and mental energy)

improving digestion

supporting hormonal balance

nourishing the skin

Studies have found that, in healthy subjects, schisandra generates alterations in the basal levels of nitric oxide and cortisol present in blood and saliva. In animal studies, it’s also been shown to help modify the response to stress by suppressing the increase of phosphorylated stress-activated protein kinase, which raises inflammation.

Schisandra has historically been taken as a tonic tea but I like eating the berries (in moderation) strait up myself as well. Unlike other herbs, it can be taken long term without any negative side effects or risks. In fact, it’s believed to work better and better the longer you take it, just like many other natural adaptogens.

Some herbs that are beneficial for improving liver function can start to become problematic if used for too long, but schisandra is safe for day-to-day use even in people with sensitive digestive systems and low tolerance to supplements.

Schisandra is a complex herb, and there are multiple mechanisms by which these constituents act like phytoadaptogens, affecting the central nervous, sympathetic, endocrine, immune, respiratory, cardiovascular and gastrointestinal systems. Research has shown that schisandra helps stall the process of oxidative stress, which contributes to nearly every disease there is and results in the loss of healthy cells, tissues and organs.

Many bioactive compounds (about 300) have been isolated and identified in different parts of S. chinensis. Phytochemical studies have demonstrated that S. chinensis contains a large number of components, for example, lignans, phtosterols, essential oils, phenolic compounds, triterpenoids, and others, in which chemical structures of lignans and triterpenoids are unique, while other compounds. Bioactive compounds in various parts of S. chinensis are demonstrated in the Figure below.

The precise phytochemical composition depends on a number of factors, including temperature, humidity, harvest time, light, geographical location, season, soil type, and maturity [1,14,15].

It also exhibits strong antioxidant activities that positively affect blood vessels, smooth muscles, the release of fatty acids into the bloodstream (such as arachidonic acid) and the biosynthesis of inflammatory compounds. This results in healthier blood cells, arteries, blood vessels and improved circulation.

This is one reason why schisandra helps increase endurance, accuracy of movement, mental performance, fertility and working capacity even when someone is under stress.

According to a report published in the Journal of Ethnopharmacology, a large number of pharmacological and clinical studies conducted over the past five decades suggest that schisandra increases physical working capacity and has strong stress-protective effects against a broad spectrum of harmful factors. Among its many uses, studies have found it helps prevent inflammation, reverse heavy metal intoxification, improve loss of mobility — plus treat heat shock, skin burns, frostbite, hormonal disorders and heart disease.

A 2015 study published by the Department of Korean Medicine at Dongguk University found that schisandra fruit positively modulates gut microbiota in a way that helps prevent various metabolic syndrome risk factors, along with potentially weight gain.

After studying markers related to metabolic diseases in 28 obese women as part of a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled study done over 12 weeks, the researchers found that compared to placebo schisandra had a greater impact on lipid metabolism and modulation of gut microbiota that resulted in a decrease in waist circumference, fat mass, fasting blood glucose and triglycerides levels.

Bacteroides and bacteroidetes were two forms of microbiota increased by schisandra that showed significant negative correlations with fat mass. Ruminococcus was another microbiota decreased by schidandra, which resulted in a decrease of high-density lipoprotein cholesterol and fasting blood glucose.

List of Health Benefits:

1. Helps Lower Inflammation

Thanks to its high concentration of antioxidant compounds, schisandra helps fight free radical damage and lowers inflammatory responses — which are at the root of modern diseases, like cancer, diabetes and heart disease. Free radicals threaten our health because they turn on and off certain genes, cause cellular and tissue damage, and speed up the aging process.

Due to its ability to positively affect the immune system and fight inflammation, schisandra helps stall the development of atherosclerosis (hardening of the arteries), balance blood sugar, prevent diabetes and bring the body into an optimal acid-base balance.

When it comes to cancer prevention, active lignans have been isolated from schisandra (especially one called schisandrin A) that have chemo-protective abilities. Studies that have investigated the effects of schisandra on organs, tissues, cells and enzymes have revealed it helps control the release of leukocytes, which promote inflammation, and improve the ability to repair tissue. It also positively impacts platelet-activating factors, metabolism, oxygen consumption, bone formation and the tolerance of toxin exposure.

According to Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center, studies using animals suggest that schisandra increases hepatic glutathione levels and glutathione reductase activities, downregulates inflammatory cytokines, activates the eNOS pathway, exhibits apoptosis (death of harmful cells), and enhances adult stem cell proliferation.

2. Aids Adrenal Function, Helping Deal with Stress

Known as an adaptogenic agent, schisandra helps balance hormones naturally and therefore improves our ability to deal with stressors, both physical and psychological.

Adaptogenic herbs and superfoods have been used for thousands of years to naturally raise the body’s resistance to environmental stress, anxiety, toxin exposure, emotional trauma, mental fatigue and mental illnesses. Because schisandra helps nurture the adrenal glands and turns down an overproduction of “stress hormones” like cortisol, it’s linked with better mental capabilities, physical endurance and metabolic health.

In 2007, the Swedish Herbal Institute Research and Development department tested the effects of adaptogen herbs, including rhodiola, ginseng and schisandra, on blood levels of stress-activated protein kinase (SAPK/JNK), nitric oxide (NO), cortisol, testosterone, prostaglandin, leukotriene and thromboxane in rats.

Researchers determined that over a seven-day period, when rats were given frequent supplementation of adaptogens/stress-protective herbs, they experienced near-steady levels of NO and cortisol despite increased amounts of stress.

The findings suggest that inhibitory effects of these adaptogens make them natural antidepressants that have positive effects on hormones and brain functions even when under stress and tiring conditions. Don’t forget there’s also a link between lower amounts of stress and better immune function: The more stress we’re under, the less capable we are of defending ourselves from disease.

3. Supports Liver Function and Digestive Health

Much of the anecdotal research on schisandra has focused on liver function, especially its effect on the production of various liver detoxifying enzymes. Its immune-boosting abilities are far-reaching because schisandra helps increase enzyme production, boost antioxidant activity, and improve circulation, digestion and the ability to remove waste from the body.

Because liver health is tied to stronger immunity, schisandra has been found to be protective against infections, indigestion and various gastrointestinal disorders.

Dozens of studies done over the past 50 years demonstrate the efficiency of schisandra in cleansing the liver, treating pneumonia, preventing developmental problems in pregnant women, and reducing allergic reactions, acute gastrointestinal diseases, gastric hyper- and hypo-secretion, chronic gastritis, and stomach ulcers. Some small studies also show it’s helpful for treating chronic hepatitis, especially when used with other treatments.

A randomized, parallel, placebo-controlled study done by the Taichung Hospital Department of Health in China showed that patients experienced improvements in liver function and relief from fatty liver disease when using a mixture of schisandra fruit extract and sesamin. Forty subjects were divided into a test group (taking four tablets daily) and a placebo group. Effects of total bilirubin, direct bilirubin, free radical levels, total antioxidant status, glutathione peroxidase, glutathione reductase and the lag time for low-density lipoprotein oxidation were all observed.

Compared to the control group, schisandra greatly increased the antioxidant capacity and decreased the values of thiobarbituric acid reactive substances, total free radicals and superoxide anion radicals in the blood. An increase in glutathione peroxidase and reductase also occurred in the group taking schisandra, while a longer time period was observed for low-density lipoprotein oxidation and inflammatory markers.

A 2010 study published in the International Journal of Clinical Pharmacology and Therapeutics found that schisandra can even benefit patients following a liver transplant, since it increases production of a compound called Tcrolimus (Tac), which prevents the body’s rejection of a new liver following liver transplantation.

Blood concentrations of Tac significantly increased in liver transplant patients after receiving schisandra sphenanthera extract (SchE). The average increase in the mean concentration of Tac in the blood was 339 percent for the group receiving higher doses of SchE and 262 percent for the group receiving lower a dose. Tac-associated side effects, such as diarrhea and indigestion, also decreased significantly in all patients as liver function improved.

4. Protects the Skin

Schisandra is a natural beauty tonic that’s capable of protecting the skin from wind, sun exposure, allergic reactions, dermatitis, environmental stress and toxin accumulation. Schisandra chinensis has been widely used to treat skin diseases due to its anti-inflammatory effects.

While more formal research on the effects on schisandra on skin health are needed, one 2015 study using rats observed that schisandra extract inhibited ear swelling by lowering skin dermatitis, immune cell filtration and cytokine production, which are all markers of inflammatory skin disorders in humans.

5. Improves Mental Performance

One of the oldest uses for schisandra is promoting mental clarity and raising energy levels. Centuries ago in Russia, it was used by the Nanai people to promote stamina for hunters going on long voyages without much rest or nourishment.

The Antioxidant Phytochemical Schisandrin A Promotes Neural Cell Proliferation. That means not only can this powerful medicine plant help prevent neurodegeneration, but it can also potentially help heal brain injuries and optimize and/or enhance cognitive function in healthy adults via initiating increased levels of neurogenesis and synaptogenesis.

Practitioners of TCM have used schisandra to naturally improve mental capabilities and promote sharper concentration, increased motivation and better memory.

One of the great thing about schisandra is that it doesn’t increase energy in similar ways to caffeine, by affecting the release of various stress hormones and altering blood sugar. As you probably know, caffeine use — especially caffeine overdose — can cause side effects like nervousness, restlessness and heart beat irregularities, but schisandra actually does the opposite. It essentially makes you feel calmer while also fighting off fatigue.

Studies also show a link between schisandra use and protection against neurological and psychiatric disorders, including:

neurosis

depression

schizophrenia

anxiety

alcoholism

even Alzheimer’s

6. Helps with Healthy Sexual Function

Research shows that schisandra is beneficial for fertility and hormonal health, helping promote a strong libido, preventing sexual dysfunction like impotence and positively affecting the reproductive organs, including the uterus. (9)

Because it positively impacts hormone production, including estrogen, it’s capable of helping with bone healing and forming bone mineral density. This is useful for preventing diseases like osteoporosis, which is common among older women as they experience changes in hormonal levels.

Due to its capacity to stimulate nitric oxide production, which dilates blood vessels and improves blood flow and sexual function, Schisandra powder extract is also recognized as an aphrodisiac and libido-boosting tonic.

Furthermore, stress is the main cause of decreased libido and sex drive. By reducing stress and promoting the health of the brain system and adrenal glands, the adaptogenic characteristics of Schisandra health benefits help aid in enhancing sexual performance.

Like Cordyceps mushroom, organic Schisandra berries are a wonderful option for enhancing sexual function since it promotes physical performance, endurance, and recovery.

7. Schisandra Contains Compounds Which Optimize Mitochondrial Health:

Schisandra contain potent adaptogens and ergogens, capable of decreasing fatigue and supporting the normal (and enhanced) functioning of cellular powerhouses—mitochondria [2,7].

Schisandra chinensis extract (SCE) has effects to enhance mitochondrial respiration and to improve cognitive function via induction of a key synaptic protein expression in hippocampus.

Over the past ten years, laboratories have attempted to define the biochemical properties of Schisandra berry in regard to its purported "Qi-invigorating" properties. We have found, for the first time, an ability of Schisandra berry to fortify mitochondrial antioxidant status, thereby offering the body a generalized protection against noxious challenges both of internal and external origin. Given the indispensable role of the mitochondrion in generating cellular energy, the linking of Schisandra berry to the safeguarding of mitochondrial function provides a biochemical explanation for its "Qi-invigorating" action.

Another study found that SCE (Schisandra chinensis extract) significantly increased expression of postsynaptic density protein 95 (PSD95), an increase that was correlated with enhanced brain-derived neurotrophic factor (BDNF) expression. These results demonstrate that SCE improves mitochondrial function and memory, suggesting that this natural compound alleviates Alzheimer’s disease (AD), dementia and aging-associated memory decline (while also serving to optimize and enhance cognitive function in healthy brains).

8. Anti-Aging and Longevity Benefits:

Their anti-aging and revitalizing actions comprise moisturizing, toning, irritation-soothing, and wound-healing, reducing dilatation of blood vessels and restoring the skin protective barrier.

S. chinensis fruit exerts a protective effect against skin photoaging, osteoarthritis, sarcopenia, senescence, and mitochondrial dysfunction, and improves physical endurance and cognitive/behavioural functions, which are linked with its general anti-aging potency.

Schisandrin B and its analogue, schisandrin C, were shown to protect human and rat foreskin fibroblasts against oxidative damage induced by artificial solar light [96,97]. These substances were proposed to be used in the prevention of skin photoaging. They exerted a protective effect by the stimulation of the production of reduced glutathione, decreased expression of matrix metalloproteinase 1, and an elastase-type protease. However, these compounds also produced ROS during their metabolism, mediated by the cytochrome P-450, and this reaction likely provoked potentiated antioxidant response by the glutathione system. Similar results were obtained for schisandrin B in the human keratinocyte-derived cell line HaCaT [98]. Schisandrin B reduced the cell death, DNA damage, and oxidation of proteins in these cells challenged by oxidative stress; and increased the expression of key enzymes of the antioxidant defence and stimulated the Nrf2 (nuclear factor erythroid 2-related factor 2) and MAPKs (mitogen activated protein kinases) pathways. Similar effects were observed for deoxyschisandrin and schisandrin B in HaCaT keratinocytes exposed to UVB. Altogether, these effects were concluded to be important in the prevention of skin aging underlined by oxidative stress.

Osteoarthritis (OA) is a joint disease, affecting the middle-aged to elderly [99]. An ethanol extract of SCE was shown to exert a protective effect against cartilage degradation [100]. This protection was underlined by a reduced production of inflammatory cytokines and tumor necrosis factor-alpha (TNFα), an inhibited expression of inducible nitric oxide synthase and cyclooxygenase-2, and increased levels of matrix metalloproteinase-13, cartilage oligomeric matrix protein, and a C-telopeptide of type II collagen.

Sarcopenia, a progressive loss of muscle strength and mass with aging, is commonly considered as an important indicator of normal aging and occurs in some diseases associated with accelerated aging [101]. SCE was shown to increase mass of skeletal muscle when treated by dexamethasone or that underwent sciatic neurectomy [102,103,104,105]. To explore the mechanisms beyond these effects, Kim et al. showed that SCE ameliorated muscle atrophy by increased protein synthesis resulting from downregulation of the mTOR/p-4E-BP1 (4E-binding protein1)/p-P70S6K (70 kDa ribosomal protein S6 kinase) pathway in human myoblasts [106]. A former work of Kang adds some information on this mechanism, pointing at heme oxygenase-1 (HO-1) and Nrf2, which can be targeted by SCE in C2C12 myoblasts [107]. As aging compromises muscle mass, amelioration of these effects by SCE can be considered as a manifestation of its anti-aging potential. In their recent work, Kim et al. showed that SCE upregulated genes whose products are important in protein synthesis and muscle growth after exercises (swimming) [108]. Additionally, SCE downregulated genes important for protein degradation. SCE also reduced the levels of ROS and lipid peroxidation, as well as upregulating some antioxidant enzymes and inhibited certain apoptotic markers. Therefore, SCE can be considered as an element to assist an exercise-based, healthy life style.

Gomisin A, another bioactive compound isolated from SCE, was shown to suppress stress-induced premature senescence and the production of proinflammatory molecules in human fibroblasts [109]. This effect was attributed to the promotion of mitochondrial biogenesis and autophagy by gomisin A in these cells, as well as its antioxidant activity. However, some aspects of that work need clarifying, including the determination of the reasons and consequences of the observed effects.

Diet supplementation with schisandrin B was shown to ameliorate age-related impairment of mitochondrial antioxidant functions in various tissues of C57BL/6J mice [110]. This suggests that schisandrin B can increase the survival of aging individuals by improvement of mitochondrial functions.

Aging is not only associated with a decline in biochemical functions, but also in behavioural/cognitive performs [113]. Yan et al., showed that a diet supplemented with extracts of SCE ameliorated cognitive deficits and Step-down type passive avoidance test, as compared to animals with non-supplemented diet [114]. These behavioural changes were associated with a decreased activity of antioxidant enzymes induced by D-galactose and a normal level of oxidative stress markers, including glutathione, malondialdehyde, and nitric oxide in the serum and various structures of the brain of treated animals [114].

In summary, SCE, its extracts, and derivatives can display beneficial effects against pathological aspects of aging in various systems used to investigate aging mechanisms, including cell cultures and animals (Figure 3).

Principal mechanisms of beneficial anti-aging actions of S. chinensis bioactive compounds include activation of the antioxidant defense system, reducing the levels of aspartate aminotransferase, alanine aminotransferase, and serum and liver glutamic pyruvic transaminase, as well as inactivation of cytochrome P450 [21]. S. chinensis bioactive compounds inhibit pro-oxidant signaling pathways: cyclooxygenase 1 and 2 (COX-1 and 2) [22], nitric oxide production [23], and gene expression of pro-inflammatory cytokines [24]. Furthermore, S. chinensis constituents block calcium channels (Ca2+) [25] and inhibit the opening of the mitochondrial permeability transition pore (mPTP), thus protecting from cell death [25,26,27]

9. Tumor Suppression and Anti-Cancer Benefits:

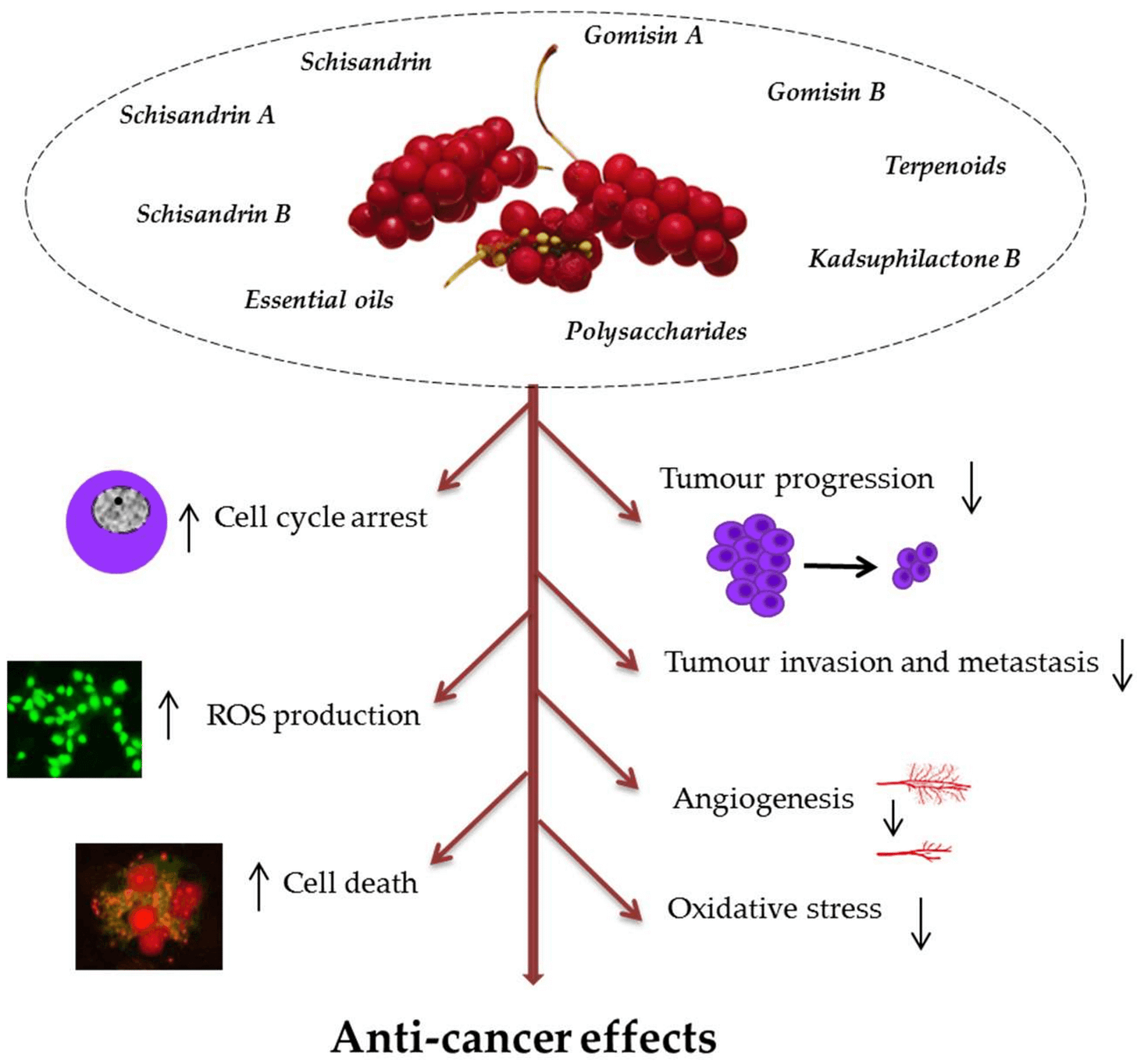

S. chinensis fruit constituents exert anti-cancer effects through several mechanisms of action. [31,32,33].

The anti-cancer activity of polyphenols from plant extracts in cancer cell lines includes several mechanisms: Inhibition of tumour proliferation, induction of cell death (apoptotic, autophagic), inhibition of tumour migration and invasion, cell cycle arrest, pro-oxidant activity by stimulation of ROS (reactive oxygen species) production in cancer cell lines, as well as reducing oxidative stress in normal cells and inhibition of carcinogen activity [48]. The main mechanisms of anti-cancer action of SCE phytochemicals are presented in the Figure (shown below).

In tumor cells, S. chinensis bioactive compounds can also sensitize tumor cells to antitumor treatments [29,30].

Schisandrin B has been shown to protect against oxidative damage in liver, heart, and brain tissues [58,59]. Cell migration and invasion are critically involved in cancer metastasis, the main cause of death in cancer patients [60]. In in vivo research, schisandrin B attenuated cancer invasion and metastasis [61]. In in vitro studies, schisandrin B inhibited the invasion and migration of the human alveolar basal epithelial adenocarcinoma cell line (A549) by down-regulating the expressions of hypoxia inducible factor (HIF-1), vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF), and matrix metalloproteinases (MMP-2 and MMP-9) [51]. Then, gomisin A reduced invasion and migration of colorectal cancer cell lines, as well as the metastasis [54] in the lung. The research relevant to mechanisms of cytotoxicity and apoptosis of SCE in cancer cells is advanced, while data on normal cells are limited and in vivo data are insufficient. Recent studies on the mechanisms of anti-cancer action of SCE are listed in the Table below.

10. Cardioprotective Effects:

In a study by Chun et al. [13] it was indicated that S. chinensis berries demonstrate protective effects against common cardiovascular diseases (CVDs) such as hypertension and myocardial infarction. They described S. chinensis fruit extract and its lignans as promising resources for the development of safe, effective, and multi-targeted agents against cardiovascular diseases.

S. chinensis components, especially lignans, may play an important role in the prophylaxis and treatment of cardiovascular diseases, including hypertension and myocardial infarction. These components, including schisandrin, are well-known Traditional Chinese Medicine formula ShengMai preparations, which act as a remedy for oxidative injury and can be used to treat various cardiovascular diseases [13,25,26,27].

In vitro and in vivo studies have found that preparations from S. chinensis berries exert their cardioprotective properties via various pathways including controlling inflammation, oxidative stress, and obesity [31,32,33,34,35].

In addition to oxidative stress, inflammatory processes also play important roles in the progress of cardiovascular diseases, including cardiomyopathy, atherosclerosis, and others.

S. chinensis fruit extract and its active constituent schisandrin B exert cardioprotective effects by enhancing the heart antioxidant defense system [57,58,59,60,61]. S. chinensis fruit extract protected from adriamycin-induced cardiotoxicity test subjects by decreasing MDA levels and increasing activities of myocardial GPx and SOD [60]. Lignan-enriched S. chinensis extract protected heart from oxidative damage in an in vivo model of myocardial infarction and an ex vivo model of myocardial ischemia-reperfusion injury [61]. Moreover, schisandrin B and C (10–30 μM), but not schisandrin A, stimulated the cytochrome P-450-catalysed NADPH oxidation reaction in in vitro studies of test subject’s heart microsomes and/or ROS production in test subjects hearts (a single dose of 1.2 mmol/kg), resulting in the increase in mitochondrial GSH levels during, thus protecting against ischemia/reperfusion injury [59]. During doxorubicin-induced cardiomyopathy, schisandrin B (25–100 mg/kg/day per os for five days) reduced lipid peroxidation, prevented nitrotyrosine formation, and suppressed metalloproteinase activation in the heart [58]. During myocardial ischemia/reperfusion (40 min + 1 h), schisandrin B (20 mg/kg) decreased MDA levels and increased total SOD activity, thus attenuating oxidative injury [57].

Zhang et al. [36] examined the effect of schisandrin in vitro on cardiomyocyte-derived cell line (H9c2) treated with LPS to model bacterial myocarditis. The cells were treated with two concentrations of schisandrin, 10 and 40 mM, for one to seven days. They found that Schizandrin promotes the recovery of myocardial tissues by enhancing cell viability and migration. Its mechanism of action includes downregulating SMAD family member 3 (Smad3), thereby reducing the activation of c-Jun N-terminal kinase (JNK) and nuclear factor kappa B (NF-κB) pathways [36].

There is also promising evidence that it can encourage Cardiac Stem Cell Activation (making it possible to initiate some degree of Endogenous Myocardial Regeneration for those that have damaged hearts).

11. Radioprotective Benefits and Protects the DNA from other types of damage

Schisandra Chinensis inhibits oxidative DNA and cell damage induced by hydroxyl radical via its antioxidant activities. In non-cellular systems, the extracts from Schisandra Chinensis effectively scavenged DPPH radical, hydrogen peroxide and hydroxyl radical, and prevented DNA damage induced by hydroxyl radical. In a cell system, the extracts also effectively inhibited intracellular DNA damage, lipid peroxidation and cell death induced by hydroxyl radical.

The data in this study indicates that Schisandra chinensis possesses a spectrum of antioxidant and DNA-protective properties.

Schisandra Chinensis have also been shown to reverse the decreases in the number of white blood cells and lymphocytes in peripheral blood after exposure to ionizing radiation. In addition, the immunoglobulin G (IgG) and complement C3 in blood serum were all decreased after radiation and Schisandra chinensis was shown to restore this radiation disorder.

Furthermore, Schisandra chinensis extract was shown to reverse the deregulation of CD3+CD4+ and CD3+CD8+ T cell subsets in peripheral blood and thymus of mice after “radiotherapy”.

Data showed that radiation-induced apoptosis of thymocytes could be reversed by Schisandra chinensis extract through inducing upregulation of Bcl-2 expression and downregulation of Fas and Bax levels. Furthermore, Schisandra chinensis has no any side-effects on immunity. Study results indicated that Schisandra chinensis extract can effectively prevent immune injury during radiotherapy by protecting the immune system. That means Schisandra chinensis may be able to help increase your body’s resilience in the presence of artificial EMFs and/or sources of ionizing radiation.

The scavenging of hydroxyl radical by the extracts from Schisandra Chinensis demonstrates its effectiveness against biologically generated radicals. Moreover, the scavenging of H2O2 by the extracts from Schisandra Chinensis demonstrates its effectiveness for inhibiting the radical generation. The present investigation also examined the ability of the extracts from Schisandra Chinensis to inhibit DNA damage in phi X-174 RF I plasmid DNA cleavage and intracellular DNA migration from exposure to hydroxyl radical.

The study linked above indicates that the extracts from Schisandra Chinensis can inhibit DNA damage caused by hydroxyl radical. Carcinogens such as chromium, aluminum, glyphosate, strontium, asbestos and nickel exert their carcinogenic effect, in part, through production of ROS (Leonard et al., 2004).

12. Schisandra chinensis Increase The Endogenous Production Of Adult Stem Cells (aka “somatic stem cells”):

S. chinensis has been shown to regulate the growth, differentiation, and activation of hematopoietic progenitors as well as enhance the development of humoral stem cells.

This study also found that other compounds in S. chinensis regulate growth, differentiation, and activation of hematopoietic cells of multiple lineages [31]. It can attract and activate eosinophils, and stimulate the proliferation of and prolong the survival of hematopoietic cells.

Analysis identified that Schisandra chinensis extract can also regulate the expression level of cell division control protein 42 (Cdc42). These findings suggest that Schisandra chinensis enhanced NPCs proliferation and differentiation possible by Cdc42 to regulated cytoskeletal rearrangement and polarization of cells, which provides new hope for the late recovery of stroke.

NPCs are self-renewing and multipotent cells that generate three major cell types in the brain called oligodendrocytes, neurons, and astrocytes [4].

Moreover, Lee et al. [4] reported that a mechanistic study showed the potential correlation between bioactive antioxidant phytochemcials and NPC regeneration is a result of their critical impact on kinase cascade activation that significantly activates endogenous neurogenesis.

SCHISANDRA CHINENSIS Key Medicinal Mechanisms:

Adaptogenic actions*

Supports endurance and working capacity* [1]

Supports resistance to stress* [1–8]

Supports healthy behavioral responses to stress* [3,4,7]

Supports a calm mood* [1,9]

Supports sleep* [1]

Supports brain function*

Supports mental performance* [1]

Supports healthy vision* [1]

Supports learning and memory in animals* [7,10–13]

Supports GABAergic neurotransmission* [3,14,15]

Supports GABA-Glutamate levels* [10,11,15,16]

Supports acetylcholine signaling* [10,11,13]

Supports serotonin signaling* [9–11,16]

Supports adrenergic signaling* [9–11,16]

Supports dopamine signaling* [9–11,16]

Supports sleep mechanisms* [14,15,17,18]

Supports brain-derived neurotrophic factor (BDNF)* [4,7]

Supports neuroprotective functions* [10–13,19,20]

Supports brain mitochondrial function* [21]

Supports antioxidant defenses* [10,19,21,22]

Supports phase II detoxifying/antioxidant enzymes* [22]

Supports a healthy gut microbiota*

Supports a healthy gut microbiota composition* [23,24]

Supports gut microbial metabolism* [24]

Supports gut immune responses* [24]

Supports healthy immune function*

Supports innate immunity* [25–27]

Supports immune function during some forms of stress* [2,28–30]

Supports immunomodulation (i.e., balance of immune function)* [31–33]

Promotes healthy aging and longevity*

Supports mitochondrial function* [19,21,34]

Supports antioxidant defenses* [21,34]

Supports autophagy* [35]

Supports healthy muscle and bone with aging* [36,37]

Schisandra’s Methods of Medicinal Use

It continues to be available in a variety or forms. In the western world of herbal medicine, the following preparation suggestions are the most widely used and accessible to obtain. It is usually available as a dried, whole berry.

Schisandra Powder

In traditional preparations, its berries were usually dried in the sun, then pounded into a powder. This powder could then be stirred into water, and drank like a tea, or added to wine, and sipped in small amounts like a tincture. In addition, it could be added to soups, sauces, or sweets; made into a pastille-like pill when bound with honey or molasses, or added to topical treatments for the skin.

To make powdered Schisandra at home, grind up the dried berries in a high powered blender until the desired consistency is achieved. For a more traditional experience, a mortar and pestle may be used to crush the berries instead.

Schisandra Decoction

Since it is often in full berry form, to make a water-based infusion, it’s highly recommended to decoct this herb. Decoctions are usually reserved for herbs that are berries, roots, barks, or mushrooms.

To make a decoction, add 1-2 teaspoons of dried berries to 10-12 ounces of water. Gently simmer for 15-20 minutes, then remove from heat to steep for 10-20 minutes longer. Strain, and enjoy!

Schisandra Tincture

It also makes a lovely tincture, as it’s both portable and easy to dose. Tinctures are usually an alcohol (at least 80 proof vodka, overproof grain alcohol, or other clear booze) extraction of a plant, however, vegetable glycerine or apple cider vinegar can be substituted to keep it alcohol-free.

To prepare a tincture, pour menstruum of choice over fresh or dried herb (1:2 alcohol to dried berry ratio) into a preferably glass container. Label and seal the jar, shake every day for at least 6 weeks. Strain, and put into a dropper bottle.

Culinary Uses:

As I write this I am chewing on several dried berries and it’s as if a thousand sour fireworks went off in my mouth. To say that this plant is extremely flavorful is an understatement! You taste the acutely sour and bitter notes as well as a peppery pungent taste. I also get some flowery notes and aromas (especially when enjoying in tea or cooked dishes).

As noted above, Chinese practitioners call it wu wei zi or “fruit of five flavors”, noting that schisandra incorporates all of the five tastes (sour, salty, bitter, sweet and pungent). Thus, it is a versatile culinary ingredient to bring depth and complexity to a range of different foods and beverages.

Chinese, Korean, and Russian cultures have used its berries in a number of ways; in beauty tonic blends, as an ingredient in soups and stews, and infused into wines.

I like to dry the berries and grind them in a pepper mill for seasoning my savory breakfast meals to give me an extra boost of adaptogenic energy for my day.

If you do get the berries, the suggested amount for medicinal purposes is 1.5 to 6 grams. A rounded tsp is about 4 grams so a little goes a long way.

To make schisandra berry tea at home, Add 1 tsp of schizandra berries for every cup of water and simmer the dried berries in a covered saucepan for 15 to 20 minutes. This will yield a much more medicinal and flavorful cup of tea than simply pouring boiled water over the herb.

Schisandra blends well with other herbal fruits such as hawthorn, elderberry and rosehips. You can also try substituting schisandra berry in any tea blend that would call for hibiscus.

Schisandra Berry Syrup

You’ve probably heard of elderberry syrup and all it’s amazing benefits. Well, it’s the same process to make syrup out of schisandra berries with different health benefits. You can take it just like you would elderberry syrup and help prevent winter time illness, namely respiratory infections.

Ingredients

3 cups cold water

1 1/2 cup schisandra berries or replace 1/2 cup with elderberries if you desire

1-2 organic cinnamon sticks

¾ to 1 cup raw local honey

1.5 ounces brandy (optional)

Directions

Combine herbs with cold water in a pot and bring to a boil. Reduce heat and allow herbs to simmer for 30 to 40 minutes.

Remove from heat and mash the berries in the liquid mixture. Strain the herbs through cheesecloth and squeeze out the juice.

Measure the liquid and add an equal amount of honey. Gently heat the honey and juice for a few minutes until well combined. Do not boil!

Stir in brandy and bottle in sterilized glass.

Label and keep refrigerated for up to 6 months.

11 Ways To Use Schisandra Berry Syrup

use to sweeten smoothies

on waffles or pancakes

in a spritzer – drizzle into some sparking mineral water, seltzer or club soda

flavor kombucha or water kefir

serve over vanilla ice cream

stir into plain yogurt

take it by the spoonful just like elderberry syrup

mix it into jam

add some to homemade gummies

stir into your favorite tea instead of honey

drizzle over baked pears or apples

Other Recipe Ideas:

Schisandra berry and beet infused Sauerkraut

(above pictures show a batch of Schisandra berry and beet infused Sauerkraut I made recently, it was delicious and I find it as a great way to start the day before a long day of physically demanding activities)

I think that these berries would be lovely in a range of different hearty soups and raw fermented hot sauces as well so I look forward to experimenting with that more as I scale up cultivation of the berries in our young food forest projects.

Functions in the context of Permaculture/Food Forest Design:

Food

Medicine

Take advantage of otherwise unproductive shady areas to produce a crop

take advantage of vertical cultivation (it is a climbing vine and can be grown up other taller ideal food forest tree species)

Soil stabilization. Their roots spread out into them, their leaves mulch them and their foliage prevent heavy rains from eroding them.

beautiful flowers so great for ornamental/medicinal residential designs

the leaves and flowers smell nice so planning then into garden designs for that benefit allows them to be very versitile

provides food for wild animals

vines drop leaves, twigs, fruits, and other organic matter to create their own mulches and nutrients on the forest floor, providing themselves with food, as well as food for an abundance of microorganisms, bacteria, fungi, shrubs, and other plant-life.

pruned vines can be harvested and used for crafting. Making products like baskets and carvings can all be wonderfully fulfilling hobbies, provide some income, and give us useful items from natural sources, as opposed to more plastic.

long lived perennial vines are also vital to the local water cycle. Their detritus allows water the chance to percolate into the soils, both feeding the plant life in it and the springs and streams running through it. The vines, in turn, transpire the water back into the atmosphere, increasing rain cycles. Meanwhile, they keep the understory moist by protecting it from evaporation and wind, as well as providing it with humidity.

In some situations vines can also be used to create living fences or privacy barriers, which cut down on material costs and farm maintenance. Plus, as with many of these other functions, these fencing trees can also provide useful outputs, like mulch, crops, and medicine. They also provide useful habitat for beneficial pest control animals and other wildlife.

Propagation

Seed can be slow to germinate. Cuttings take well[16]. Shoots can be layered in autumn[6] and removed the following year[1].

Seed

Seed can be sown in autumn.[3][6][10]. Some sources recommend exposing seed sown in nursery trays to the winter elements (except in high winter rain fall areas), expecting germination in the spring, or cold stratifying the seed in a refrigerator for 3 months and sowing in the spring[3][1]. Other sources recommend keeping autumn sown seed in a cold frame[6][10] or pre-soaking stored seed for 12 hours in warm water and sowing in a greenhouse in the spring[10].

When true leaves appear transplant starts to their own pots and grow for a year or two before planting out[3].

I am trying to germinate seeds using several methods right now and will report back on what method yields the best success.

More info on optimizing your seeding strategies for this medicine plant’s sometimes tough to germinate seeds:

Seed sources:

https://strictlymedicinalseeds.com/product/schisandra-official-schisandra-chinensis-seeds/

https://twiningvinegarden.com/shop/trees-shrubs/foliage/schisandra-chinensis-magnolia-vine-seeds/

https://herb-whisperer.com/product/wuweizi-schisandra-chinensis

Rooted cuttings

Take semi-ripe cuttings in summer[1][17][16], 5 - 8cm with a heel[17][16]. Overwinter in the greenhouse and plant out in late spring[17][16].

For more info: https://plant-journal.uaic.ro/docs/2011/3.pdf

Cultivation

Given a suitable site, S. chinensis is an ideal candidate for forest gardening[3]. Soils should be rich and well-drained yet moisture retentive[3][17][6]. Prefers a slightly acid soil but tolerates some alkalinity if plenty of organic matter is added to the soil[6]. Prefers light to deep shade[3][18] and requires some protection from the most intense sunlight[6]. Vines can become heavy, so provide a sturdy trellis or strong tree for them to climb[3]. Plants will also happily scramble over rocks, walls etc.[1].

The fully dormant plant is hardy to about -17°c, though the young growth in spring can be damaged by late frosts. Prune in late winter[1] or spring[18][1].

Although generally regarded as dioecious (male and female plants must be grown if seed is required) some reports claim that most selections are actually monoecious (bearing both male and female flowers on a single plant)[1]. One such selection is 'Eastern Prince.' It bears both male and female flowers and is very productive with large fruit[1].

more info:

Crops

The fruits of S. chinensis are regarded as one of the fundamental herbs in traditional Chinese medicine.[3]

Fruit

Fruit is juicy, delicate and thin skinned. Fruit harvest can begin 5 - 7 days before fully ripe when they are still hard and easier to pick. They ripen quickly after harvest.[1] Good quality fruit is considered to be large with thick, purplish red, fleshy and oily pulp and an intense aroma.[3]

References:

[1]A. Panossian, G. Wikman, J. Ethnopharmacol. 118 (2008) 183–212.

[2]J. Li, J. Wang, J.-Q. Shao, H. Du, Y.-T. Wang, L. Peng, Chin. J. Integr. Med. 21 (2015) 43–48.

[3]T. Yan, M. Xu, B. Wu, Z. Liao, Z. Liu, X. Zhao, K. Bi, Y. Jia, Food Funct. 7 (2016) 2811–2819.

[4]T. Yan, M. Xu, S. Wan, M. Wang, B. Wu, F. Xiao, K. Bi, Y. Jia, Psychiatry Res. 243 (2016) 135–142.

[5]Sun L.-J., Wang G.-H., Wu B., Wang J., Wang Q., Hu L.-P., Shao J.-Q., Wang Y.-T., Li J., Gu P., Lu B., Zhonghua Nan Ke Xue 15 (2009) 126–129.

[6]N. Xia, J. Li, H. Wang, J. Wang, Y. Wang, Exp. Ther. Med. 11 (2016) 353–359.

[7]T. Yan, B. He, S. Wan, M. Xu, H. Yang, F. Xiao, K. Bi, Y. Jia, Sci. Rep. 7 (2017) 6903.

[8]Xia P., Sun L.-J., Wang J., Zhonghua Nan Ke Xue 17 (2011) 472–476.

[9]W.-W. Chen, R.-R. He, Y.-F. Li, S.-B. Li, B. Tsoi, H. Kurihara, Phytomedicine 18 (2011) 1144–1147.

[10]Y. Liu, Z. Liu, M. Wei, M. Hu, K. Yue, R. Bi, S. Zhai, Z. Pi, F. Song, Z. Liu, Food Funct. 10 (2019) 432–447.

[11]B.-B. Wei, M.-Y. Liu, Z.-X. Chen, M.-J. Wei, Acta Pharmacol. Sin. 39 (2018) 616–625.

[12]N. Egashira, K. Kurauchi, K. Iwasaki, K. Mishima, K. Orito, R. Oishi, M. Fujiwara, Phytother. Res. 22 (2008) 49–52.

[13]V.V. Giridharan, R.A. Thandavarayan, S. Sato, K.M. Ko, T. Konishi, Free Radic. Res. 45 (2011) 950–958.

[14]C. Zhang, X. Mao, X. Zhao, Z. Liu, B. Liu, H. Li, K. Bi, Y. Jia, Fitoterapia 96 (2014) 123–130.

[15]N. Li, J. Liu, M. Wang, Z. Yu, K. Zhu, J. Gao, C. Wang, J. Sun, J. Chen, H. Li, Biomed. Pharmacother. 103 (2018) 509–516.

[16]B. Wei, Q. Li, R. Fan, D. Su, X. Chen, Y. Jia, K. Bi, J. Pharm. Biomed. Anal. 88 (2014) 416–422.

[17]H. Zhu, L. Zhang, G. Wang, Z. He, Y. Zhao, Y. Xu, Y. Gao, L. Zhang, J. Food Drug Anal. 24 (2016) 831–838.

[18]F. Huang, Y. Xiong, L. Xu, S. Ma, C. Dou, J. Ethnopharmacol. 110 (2007) 471–475.

[19]N. Chen, P.Y. Chiu, K.M. Ko, Biol. Pharm. Bull. 31 (2008) 1387–1391.

[20]C.-L. Li, Y.-H. Tsuang, T.-H. Tsai, Nutrients 11 (2019).

[21]K.M. Ko, N. Chen, H.Y. Leung, E.P.K. Leong, M.K.T. Poon, P.Y. Chiu, Biofactors 34 (2008) 331–342.

[22]S.Y. Park, S.J. Park, T.G. Park, S. Rajasekar, S.-J. Lee, Y.-W. Choi, Int. Immunopharmacol. 17 (2013) 415–426.

[23]M.-Y. Song, J.-H. Wang, T. Eom, H. Kim, Nutr. Res. 35 (2015) 655–663.

[24]Y. Qi, L. Chen, K. Gao, Z. Shao, X. Huo, M. Hua, S. Liu, Y. Sun, S. Li, Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 124 (2019) 627–634.

[25]M. Kortesoja, E. Karhu, E.S. Olafsdottir, J. Freysdottir, L. Hanski, Free Radic. Biol. Med. 131 (2019) 309–317.

[26]T. Zhao, Y. Feng, J. Li, R. Mao, Y. Zou, W. Feng, D. Zheng, W. Wang, Y. Chen, L. Yang, X. Wu, Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 65 (2014) 33–40.

[27]T. Zhao, G. Mao, R. Mao, Y. Zou, D. Zheng, W. Feng, Y. Ren, W. Wang, W. Zheng, J. Song, Y. Chen, L. Yang, X. Wu, Food Chem. Toxicol. 55 (2013) 609–616.

[28]L.-M. Zhao, Y.-L. Jia, M. Ma, Y.-Q. Duan, L.-H. Liu, Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 76 (2015) 63–69.

[29]J. Yu, L. Cong, C. Wang, H. Li, C. Zhang, X. Guan, P. Liu, Y. Xie, J. Chen, J. Sun, Exp. Ther. Med. 15 (2018) 4755–4762.

[30]S.-H. Tang, R.-R. He, T. Huang, C.-Z. Wang, Y.-F. Cao, Y. Zhang, H. Kurihara, J. Ethnopharmacol. 134 (2011) 141–146.

[31]Y.H. Kang, H.M. Shin, Immunopharmacol. Immunotoxicol. 34 (2012) 292–298.

[32]H. Kim, Y.-T. Ahn, Y.S. Kim, S.I. Cho, W.G. An, Pharmacogn. Mag. 10 (2014) S80–5.

[33]A.Y.S. Yip, W.T.Y. Loo, L.W.C. Chow, Biomed. Pharmacother. 61 (2007) 588–590.

[34]P.Y. Chiu, H.Y. Leung, M.K.T. Poon, K.M. Ko, Biogerontology 7 (2006) 199–210.

[35]Y. Lu, W.-J. Wang, Y.-Z. Song, Z.-Q. Liang, Pharm. Biol. 52 (2014) 1302–1307.

[36]K.-Y. Kim, S.-K. Ku, K.-W. Lee, C.-H. Song, W.G. An, J. Ethnopharmacol. 212 (2018) 175–187.

[37]J.-S. Kim, J.S. Takanche, J.-E. Kim, S.-H. Jeong, S.-H. Han, H.-K. Yi, Phytother. Res. 33 (2019) 1865–1877.

[38]H.-F. Chiu, T.-Y. Chen, Y.-T. Tzeng, C.-K. Wang, Phytother. Res. 27 (2013) 368–373.

[39]D. Tsi, A. Tan, Bioinformation 2 (2008) 249–252.

[40]G. Aslanyan, E. Amroyan, E. Gabrielyan, M. Nylander, G. Wikman, A. Panossian, Phytomedicine 17 (2010) 494–499.

[41]N. Kormosh, K. Laktionov, M. Antoshechkina, Phytother. Res. 20 (2006) 424–425.

https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/28384001/

https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S1878535223006408#b0380

https://pfaf.org/user/plant.aspx?latinname=Schisandra+chinensis

https://cmjournal.biomedcentral.com/articles/10.1186/s13020-024-00879-0

https://practicalplants.org/wiki/schisandra_chinensis/

https://thenaturopathicherbalist.com/2015/09/13/schisandra-chinensis/

https://greenmedinfo.com/gmi-search?text=schisandra%20chinensis

https://theherbalacademy.com/blog/schisandra-berry-syrup/

https://www.plantintroduction.org/index.php/pi/article/view/1556/1497

https://mykoreankitchen.com/sparkling-strawberry-punch/

https://www.flowerfolkherbs.com/articles/schisandra-the-berry-that-does-it-all

https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC6397880/

https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/30858859/

https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fnut.2023.1227027/full

https://www.researchgate.net/publication/340182088_Schisandra_Extract_and_Ascorbic_Acid_Synergistically_Enhance_Cognition_in_Mice_Through_Modulation_of_Mitochondrial_Respiration

The above post was the 5th installment of a series titled Stacking Functions in the Garden, Food Forest and Medicine Cabinet : The Regenerative Way From Seed To Apothecary.

Stacking Functions in the Garden, Food Forest and Medicine Cabinet : The Regenerative Way From Seed To Apothecary

·Hello everyone! I am announcing a new series which will eventually get compiled and formatted into my next book. Recipes For Reciprocity: The Regenerative Way From Seed To Table is a book that I wrote to offer techniques, perspectives and recipes that invite …

Wow! Thank you so much for this in-depth article on schisandra! I appreciate your time and all the detailed information. I'll be saving this article and referring back to it as I figure out how to source, grow and use it. I hope to use it to improve my health. 🤞

Much respect and kind regards!

Keep us posted on your seed germination.

Thanks again.

Carol

I was left with a single plant which appears to have produced flowers and now primordial fruit. Which suggests it is self fertile. I have since planted a named self fertile variety (“Eastern Prince”) next to it so perhaps they are both self fertile varieties.

Thanks for the excellent info and all you do.