The Wild Apples of the Tian Shan Mountains

This article explores the origin of modern apples, info on why preserving the original wild apple genetics is important and some updates on our efforts to do so in our forest garden.

I am someone that has loved apples since a relatively young age as I grew up on an apple orchard in the South Okanagan of BC where my parents grew some superb apples in excellent soil. I found great joy in being able to wake up in the morning and pick a couple juicy apples fresh off the tree on my way to school in autumn or before setting out on an adventure on the weekends. Later in life my interest in seed saving, preserving ancient heirloom varieties and breeding new ones increased and so I inevitably came to wonder “where did modern apples come from?”. After some extensive research into the genetics of modern apples, root grafted vs apple trees grown from open pollinated seed and looking into where the wild relatives of domesticated apples still grow, I discovered Malus sieversii.

It was named after the German botanist Johann August Carl Sievers, member of the Russian Imperial Academy of Sciences, who made several expeditions in Siberia and in Central Asia at the end of the 18th century, and would have been one of the first to officially ‘discover’ the wild apple tree forests in southeast Kazakhstan.

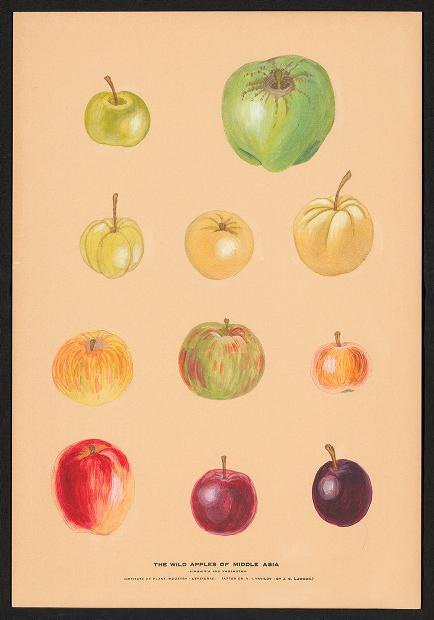

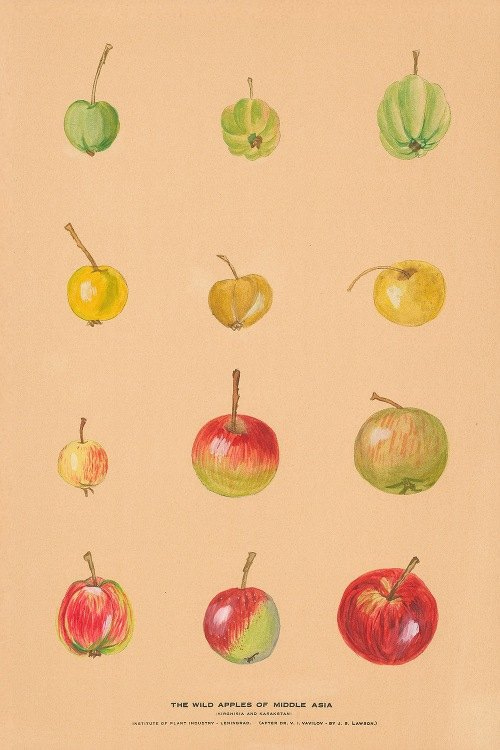

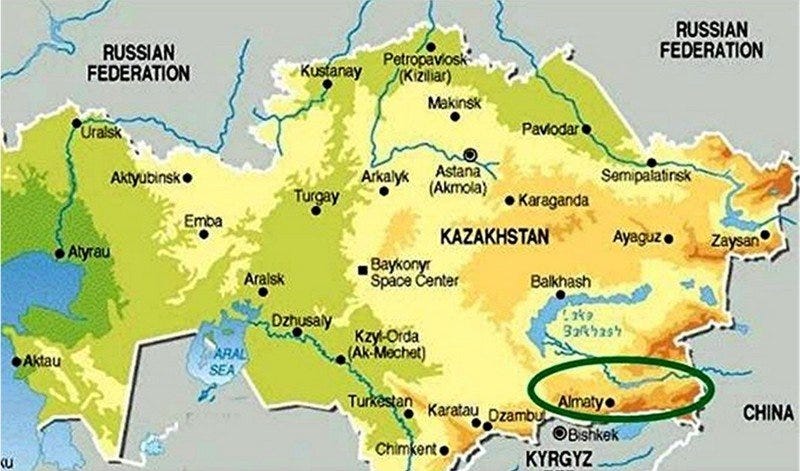

More recently, Nikolai Vavilov (a Soviet-era botanist) studied the origin of the apple, and concluded that the domestic apple (Malus domestica) had evolved from a species of wild apple (Malus sieversii), endemic to Southern Kazakhstan. That theory that all domestic apples originate from the mountains in southern Kazakhstan has since been confirmed by modern genetics.

When Nikolai Vavilov first identified the Malus sieversii as the progenitor of the domestic apple, Malus domestica, in 1929, the region’s forests were thick and their harvests bountiful.

He first traced the apple genome back to a grove near Almaty, a small town whose wild apples are nearly indistinguishable from the Golden Delicious and other common apple varieties found at grocery stores today. Vavilov visited Almaty and was astounded to find apple trees growing wild, densely entangled and unevenly spaced, a phenomenon found nowhere else in the world.

“All around the city one could see a vast expanse of wild apples covering the foothills,” wrote Vavilov of his visit to Almaty, then Kazakhstan’s capital. “One could see with his own eyes that this beautiful site was the origin of the cultivated apple.”

Almaty’s former name, Alma-Ata, means “father of apples,” and the town touts its heritage proudly. A fountain in the center of town is apple-shaped, and vendors come out each week to sell their many varieties of domesticated apples at market. Apples weren’t always a precious fruit in Almaty though.

They used to be commonplace, and during Soviet development many of the wild apple trees were cut down for their wood. Up to 80 percent of the wild apple forests were destroyed.

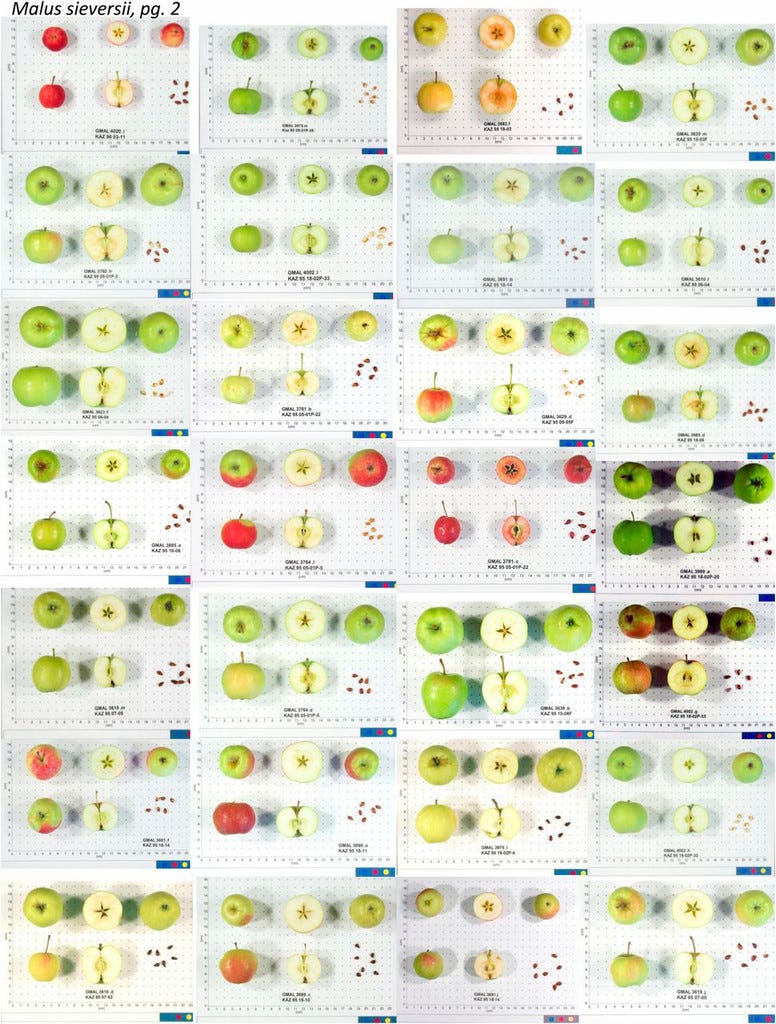

Despite that unfortunate devastation of ancient apple forests, there are still wild apple forests in the Tien Shan Mountain range of Kazakhstan today. In these forests, no two trees produce identically flavored apples. The interesting thing about Malus sieversii is that unlike many other wild trees, the fruits from one tree are completely different from the next — the flavors are remarkably diverse. Some fruit are said to have a flavor reminiscent of wine, through apricot to bitter lemon or rhubarb. Tastes are said to range in intensity through notes of sweet, sour, and bitter. The texture could be anywhere from crunchy to mealy, and the size anywhere between a cherry and a tennis ball.

The entire gene pool for apples, no matter what variety, is contained in the Kazakh apple trees. This rich diversity came about because of their isolation, which lasted about 6,000 years. This deep genetic reservoir is contained within each wild apple (Malus sieversii) seed. In another blog post I did a thought experiment in an effort calculate the latent value that is contained within an heirloom seed (which is unlocked and multiplied exponentially each time we share those seeds). Given the immense potential held within each Malus sieversii for breeding countless new varieties that offer not only new flavors and higher nutritional content, but disease tolerant trees and drought tolerant trees, the latent value contained within a handful of Malus sieversii seeds is many magnitudes greater than a handful of kale seeds or elderberry seeds (which, considering the math I laid out in my previous blog post is saying something).

There are essentially three researchers/scientists we can thank for making us aware of this critically important gene pool which is contained within Malus sieversii.

Firstly, Nikolai Ivanovich Vavilov (some of his important work was described above).

Vavilov organized a series expeditions to collect seeds from every part of the world and created the largest collection of plant seeds in existence at that time. This seed bank contained apple seeds from his visit to the Kazakh apple forests.

Secondly, Aimak Dzangaliev

Aimak Dzangaliev, was is a conservationist and a citizen of Almaty. Since 1929 he devoted his life to the apple forest. Even at his advanced age, he was still working actively in his quest to study and conserve the diversity of apples and other wild fruits in his beloved forests as recently as ten years ago. His long life, he says, is due to his wife, Tatiana's, insisting that he eat several kinds of wild apples daily (when in season) every year since they were married.

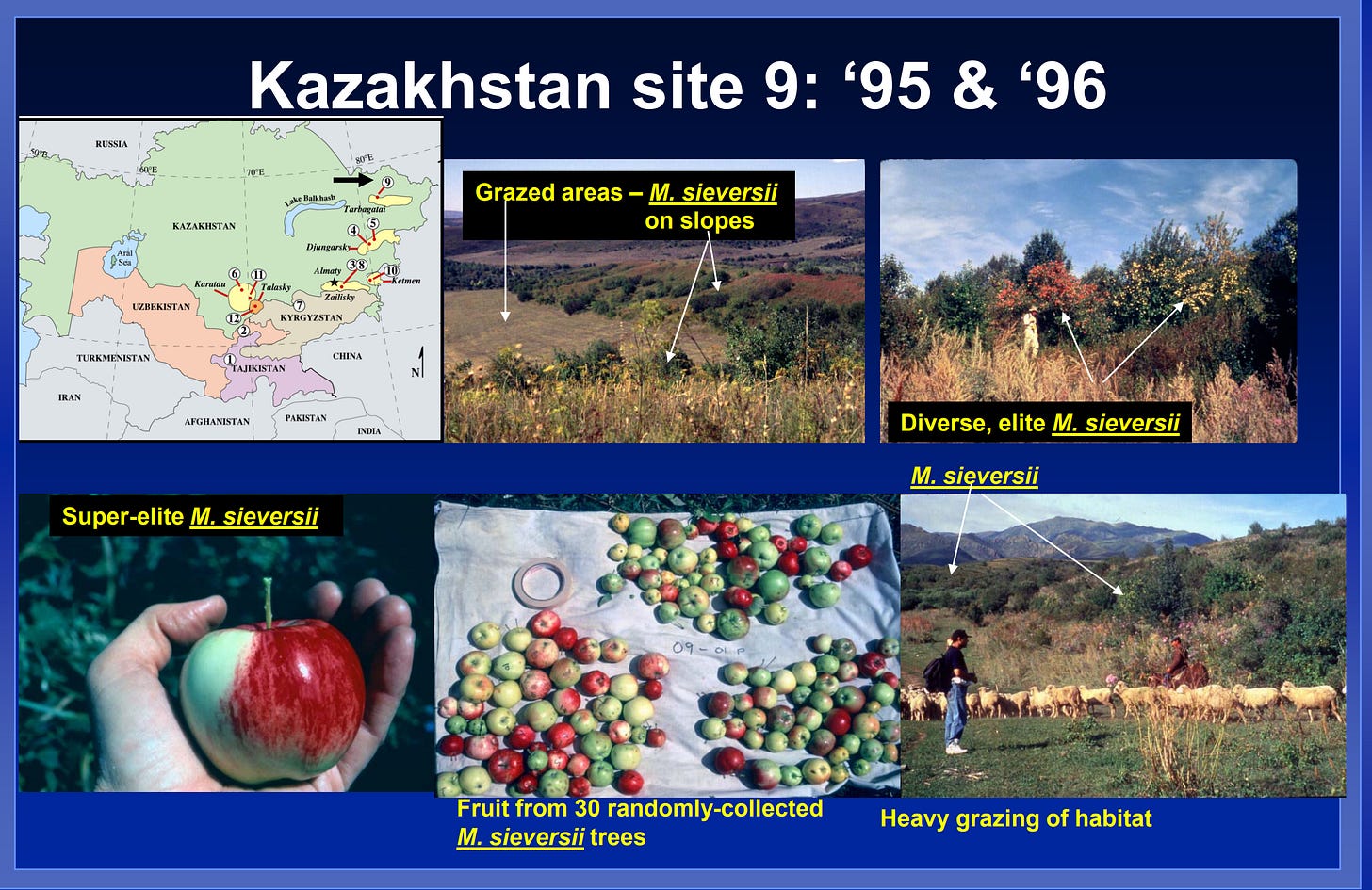

And Thirdly, Philip Forsline

Philip Forsline has been curator of the apple collection at the USDA-ARS Plant Genetic Resources Unit at the New York State Agricultural Experiment Station since 1984. For over a decade he visited the apple forests of Kazakhstan every couple years and brought back with him seeds from every new type of Malus sieversii he found growing there. As of 2010, he had about 2,500 varieties of apples growing in his collection in Geneva, New York, and had tasted every single one.

One visitor to his wild apple tree collection in Geneva said “At least eight varieties tasted hauntingly of roses. Several surprised me with the distinct taste of anise or fennel. There were aromas of all kinds. Flowers and spices and nuts, including coconut. Lots of other fruits: orange peel and lemon, strawberry, pineapple, green banana. Rhubarb. Occasionally, popcorn, and potatoes. Some apples seemed to suffer from confused genus identity and tasted like pears.”.

I do not know the current status of that collection.

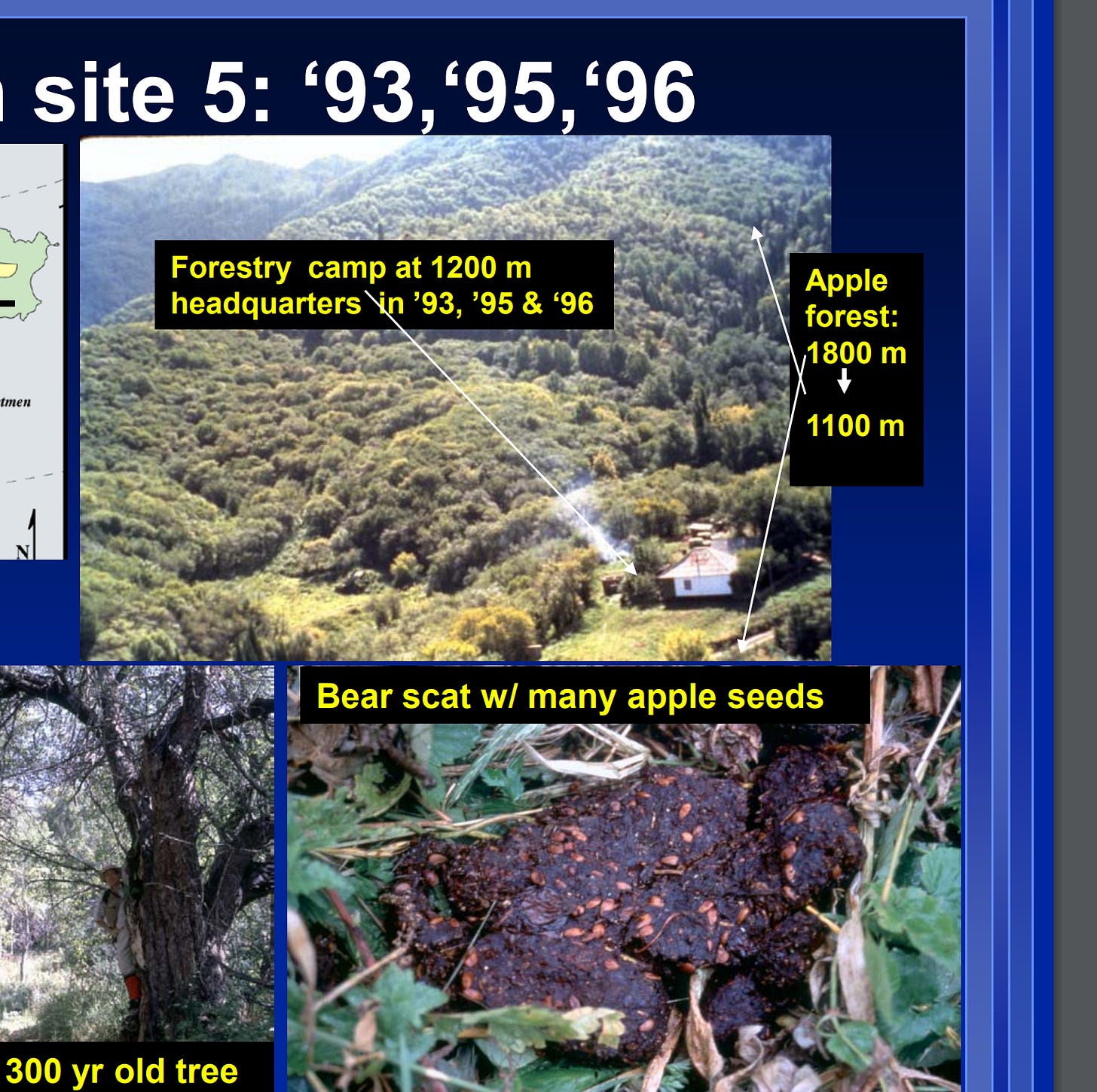

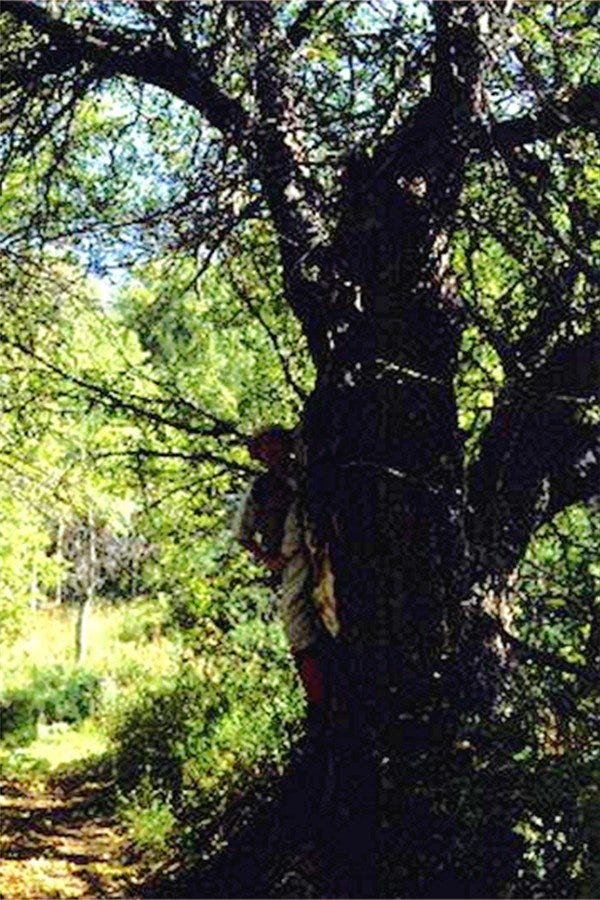

While in Kazakhstan on one of his research trips Philip Forsline (a US government horticulturalist) went traveling to the Tian Shan mountains and marveled at forests consisting almost entirely of wild fruit and nut trees, with 300-year-old apple trees 5 feet across at the base and 60 feet tall.

As you will see from the pictures I will share below this, these wild apples thrive in a wide range of climate and soil conditions.

“There were apples of all sizes and colors. Some were so pale that they looked like snowballs hanging on the trees,” he said.

So prolific are apples in the region, that he saw apple trees coming up in the cracks of the sidewalks in towns near the forests.

Success Against Plant Diseases

Forsline says the Kazak trees (when tested in his research facility in Geneva) showed significant resistance to apple scab, the most important fungal disease of apples, whose outbreaks blemish fruit and defoliate trees. “Twenty-seven percent of the Kazak accessions were resistant to it,” he says. “This makes sense, because the tree co-evolved with the disease, through natural selection.”

And researchers have found genes in these apples that allow them to adapt to mountainous, near-desert, and cold and dry regions. The trees can resist strongly fluctuant temperature, going from -40°C (-40°F) degrees during winter to 40°C (104°F) degrees in the summer.

This makes Malus sieversii an ideal candidate for including in a Food Forest design. I explore the many reasons why creating resilient food forest gardens is imperative in the context of our current fragile food infrastructure, the imperialistic endeavors of plutocrats that are seeking to dominate food production systems via the hyper consolidation of seed company ownership, economic collapse, war and the exposure of a food system to energy price shocks, supply chain breakdowns and commodity market speculation in a past blog post which you can find here.

Malus sieversii is currently listed as ‘vulnerable’ on the ICUN Red List (last assessed in 2007), with its population ‘decreasing’. Threats to the few remaining forests include residential and commercial development, livestock farming and deforestation. Its habitat has declined by over 70% in the last 20 years. Genetic erosion from grafting of commercial varieties and hybridization are also a threat to the species survival in the wild.

Moves have recently been made to preserve those that remain in the Trans-Ili Alatau foothills by Italy’s Slow Food foundation (which requires permits for visitors to enter the forest) with funding from Cultures of Resistance Network.

The apple forests only exist in patches along the Tian Shan mountain range now (due to human development. There are various protected sections in the Ile-Alatau National Park, but hiring a guide to take you there is recommended as they are difficult to find.

Some theorize that Ice Age-era humans would have been quick to recognize this kind of culinary paradise, as some early humans left their marks in the form of seemingly ritualistic petroglyphs on rocks throughout the valleys. One can imagine them sitting under one of these trees feasting on the apples, and where they threw the core or deposit humanure after eating the seed, another tree would grow. After generations of always eating the sweetest and biggest fruit and then unintentionally sowing the seeds, the fruit changed, got reliably bigger and sweeter, closer to the apples we are familiar with today.

“At some point, either seeds, trees or budwood from desirable trees was taken out of the [Malus sieversii] forests by humans and grown elsewhere,” said Gayle Volk, a research plant physiologist at the United States Department of Agriculture (USDA). “In some cases, those trees could have hybridized with wild apple species growing in other regions. The selection process continued.”

By the time humans did begin to grow and trade apples, the Malus sieversii had already taken root in Syria. The Romans discovered it there, and dispersed the fruit even further around the world. When modern genome sequencing projects affirmatively linked domestic apples to Malus sieversii, Almaty and its surrounding land were officially recognized as the origin of all apples.

Though in my opinion, the story of how the apple made it from a remote mountain to your garden or orchard has as much to do with birds, boars, deer, bears and horses as it does with primitive humans or nomads. Birds are thought to have carried the seeds of an early apple from China to Kazakhstan, where the Tien Shan brown bear fell in love with them. Bears like big, juicy apples and will hack their way through a tree to get the best fruit, pruning the trees as they go. They poop out the seeds in a perfect germination package.

Thus it is thought that a key element in the selection and breeding of apples has been bears. The bears always choose to eat the sweetest apples, and at the time of ripening, gorge themselves on the fruit before a long winter in hibernation. The seeds pass through the bears unharmed, and more apple trees with preferential genes are propagated in spring.

Bears don’t roam a great deal, but horses do, and Kazakhstan was one of the first places where they were domesticated. Horses love apples, and distribute the bear-selected apples far and wide. Horses — which were first domesticated in Kazakhstan for riding and milk facilitating great journeys along the Silk Road, dispersed the seeds all along their way.

From Kazakhstan, the seeds of many types of apples were dropped by traders along the Silk Road to Asia and to Europe, and eventually made their way to North America with the early colonists who planted apple orchards, spreading the apple genes throughout the northeast, and eventually all throughout the U.S. and Canada

But apples, like humans, do not produce carbon copies of themselves in their seeds, so each seed in an apple is as different from another seed in that same apple or from another seed in an apple on the same tree, as children are different from each other and from their parents.

Here is where the problem with modern apples arises, along the way from the Tian Shan Mountains to our backyards apple trees lost something essential: genetic diversity.

The almost complete dependence of modern apple cultivation on grafting to root stock for uniform and reliable fruit production is the cause of the problem.

“Most of the apple trees in the world are planted on M.9 rootstock,” says Gennaro Fazio, a plant geneticist with the U.S. Department of Agriculture’s Agricultural Research Service. “They’re clones of a tree that grew in the 17th century. That’s ancient technology.”

Rootstocks are used in grafting when the branch of a desirable fruit tree is spliced into the trunk of another. M.9 is used to dwarf, or shrink, the size of a fruit tree. A Gala, Fuji, or Red Delicious grown from seed will become tall and unmanageable, but if you graft their scions (branches) onto M.9 rootstock, the resulting tree will be only one-third the height. This results in a smaller canopy that allows more sunshine through, creating better and more consistent apples on each tree. And the lower height makes for more efficient harvesting.

The term M.9 is short for Malling 9, a code given to the rootstock in 1912 when it was officially cataloged at the East Malling Research Station in Kent, England.

What those early botanists were doing, unknowingly, was narrowing the apple tree’s genetic pool to the point where a mutation occurred. In this case, in the form of a the M.9’s shrimpy size. That process also eliminated genes that helped the tree fight pests and diseases.

While M.9’s adaptation and evolution was stopped in time (the moment humans began grafting onto root-stock) Mother Nature and all her ‘pests’ and disease pressures kept on developing ways to put pressure on it.

The result is that today’s M.9 rootstocks are vulnerable to an array of maladies, such as fire blight, woolly apple aphid, and cedar apple rust.

The disease that really concerns Fazio is replant disease. Wherever multiple generations of M.9 have been replanted, the rootstock is attacked from something in the soil. Scientists don’t fully understand why.

“That’s not a problem for sieversii,” Fazio says. “They’ve been replanting themselves in the wild for thousands of years. That’s a trait we want to get back.”

Michael Pollan (author of The Botany of Desire.) wrote “the story of the modern apple, which has become utterly dependent on us to keep its natural enemies at bay, suggests that domestication can be overdone.”

Malus sieversii is a valuable resource for its ability to grow without pesticides also in harsh climates. With recent erratic weather patterns, the industrial apples aren’t set to cope with the extremes we face as we strive to grow food for ourselves and our communities, which makes it even more relevant to preserve robust species such as this ancient apple.

Key points on the importance of preserving Malus sieversii for future generations:

Gathering, saving and growing wild seeds from the progenitor species of our favorite domesticated crops is critical in protecting our food supply from crop diseases, insect pests, and catastrophic weather.

It is estimated that 16,000 apple varieties existed four centuries ago. By 1907, that number was whittled down to 7,098. Today, just 15 varieties compose 90% of all apples sold in grocery stores. By narrowing the commercial apple gene pool to 15 varieties, we have set ourselves up for a catastrophic event on a scale much larger than the Irish potato famine. Our modern apples have almost no disease resistance left. That is one of the reasons why the apples in Kazakhstan are so important.

The apples now on the market are subject to apple scab, cedar apple rust, fire blight, powdery mildew, and the exit wounds of coddling moths.

Consumers are put off by the slightest imperfection, so growers spray their apples an average of 10 times a year.

The native apples of Kazakhstan have an incredible amount of disease resistance.

In addition to the cultural, agricultural and botanical imperatives for protecting the wild apple from extinction there are also nutritional and medicinal arguments for the importance of protecting this ancient ancestor of the modern apple.

Malus sieversii has been recently used as a critical source in the breeding of red-fleshed apples, due to its high genetic variability. This is seen as they are used to improve the stress resistance towards drought, cold, and pests of cultivated apple species.[21] Some characteristics of M. sieversii, such as high-flavonoid contents (especially anthocyanin) and short juvenile phases, have recently been used for red-fleshed apple breeding since traditional red-fleshed apples are not rich in these flavonoids. Using M. sieversii for breeding due to its high anthocyanin content has numerous benefits, including preventing cardiovascular disease and protecting against liver damage

“People have been touting the health benefits of apples for at least 5000 years,” says author Jo Robinson in her book, Eating on the Wild Side. “Our well-known rhyme ‘An apple a day keeps the doctor away’ is a remake of a 19th century Welsh saying: ‘Et an apple before gwain to bed maketh the doctor beg his bread,’”. Apples have symbolized health and longevity throughout recorded history.

But Robinson quickly emphasizes that most modern-day apple varieties have lost their medicinal properties when she says, “Wild apples—apples the way nature made them—may indeed help us live longer and healthier lives. In a 2003 survey, USDA fruit researchers measured the phytonutrient content of 321 wild and domesticated apple trees. The lab tests showed that the wild apples were vastly more nutritious than our cultivated varieties. One wild species had 15 times more phytonutrients than the Golden Delicious variety. Another species had 65 times more.

Apples are high in phytonutrients, the compounds in plants that have health-promoting properties including antioxidant, anti-inflammatory, and liver-health-promoting activities. They are also high in soluble fiber, which can help reduce cholesterol and prevent heart disease. Any apple will have both fiber and phytonutrients, but not all apples are created equally. United States Department of Agriculture (USDA) research shows that wild varieties of apples are vastly more nutritious than cultivated varieties (like you get in a grocery store). In fact, wild apples, depending on the variety, have up to 475 times more phytonutrients than many cultivated varieties.

Another study found that the concentration of the health promoting phytonutrients and antioxidant compounds (through which the saying “an apple a day keeps the doctor away” is derived was 17-fold and 9-fold higher than observed in the average domesticated store bought apple (M. domestica).

The study results indicated that the wild apples have a significantly higher total polyphenols content than domesticated apples. The phytochemical analysis led to the determination of 25 polyphenolic compounds including phenolic acids, flavonols, flavan-3-ols, procyanidins, and dihydrochalcones. Amongst the analyzed polyphenols, chlorogenic acind, B-type procyanidins, phloretin-2-glucoside, p-coumaric-4-O-glucoside acid quercetin-O-glucoside,and quercetin-O-galactoside were found to be dominant.

Additional info on the many health benefits of eating apples can be found here, here and here.

Bringing The Wild Apple Forests To Canada

The information above (combined with my love of seed saving, heirloom breeding, bolstering food security and forest gardening) are some of the reasons why decided to try and grow some wild apple trees here in Canada. These ancient wild apples are a living genetic database that contains the potential for countless new apple varieties to be developed that would be resilient to pest and disease pressures and offer a wide diversity in flavor, nutrition and form.

I am grateful to have managed to secure some Malus sieversii seeds from southern Kazakhstan and also found a specialized cold hardy tree nursery in Quebec that has already grown out some seeds and is selling bare root seedlings. The seeds we secured from a direct source (an acquaintance in Almaty, Kazakhstan) germinated and grew many seedlings which contain the genetic essence of the original apple progenitor (“the father of all apples”). We now have three 6 year old trees and several 2, 3 and 5 year old trees going which we grew from seed.

The aphids took a few swings at our baby trees but with some blasts of water and a little help from our wasp, hornet and ladybug friends the population was kept low and the seedlings managed to acclimatize well in their new home.

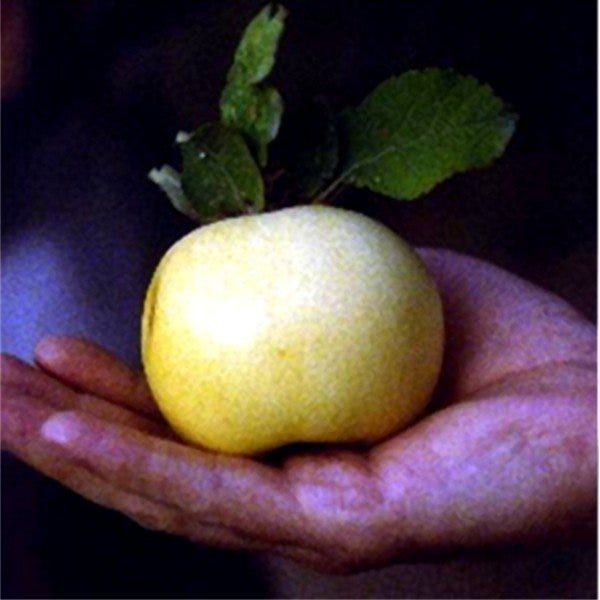

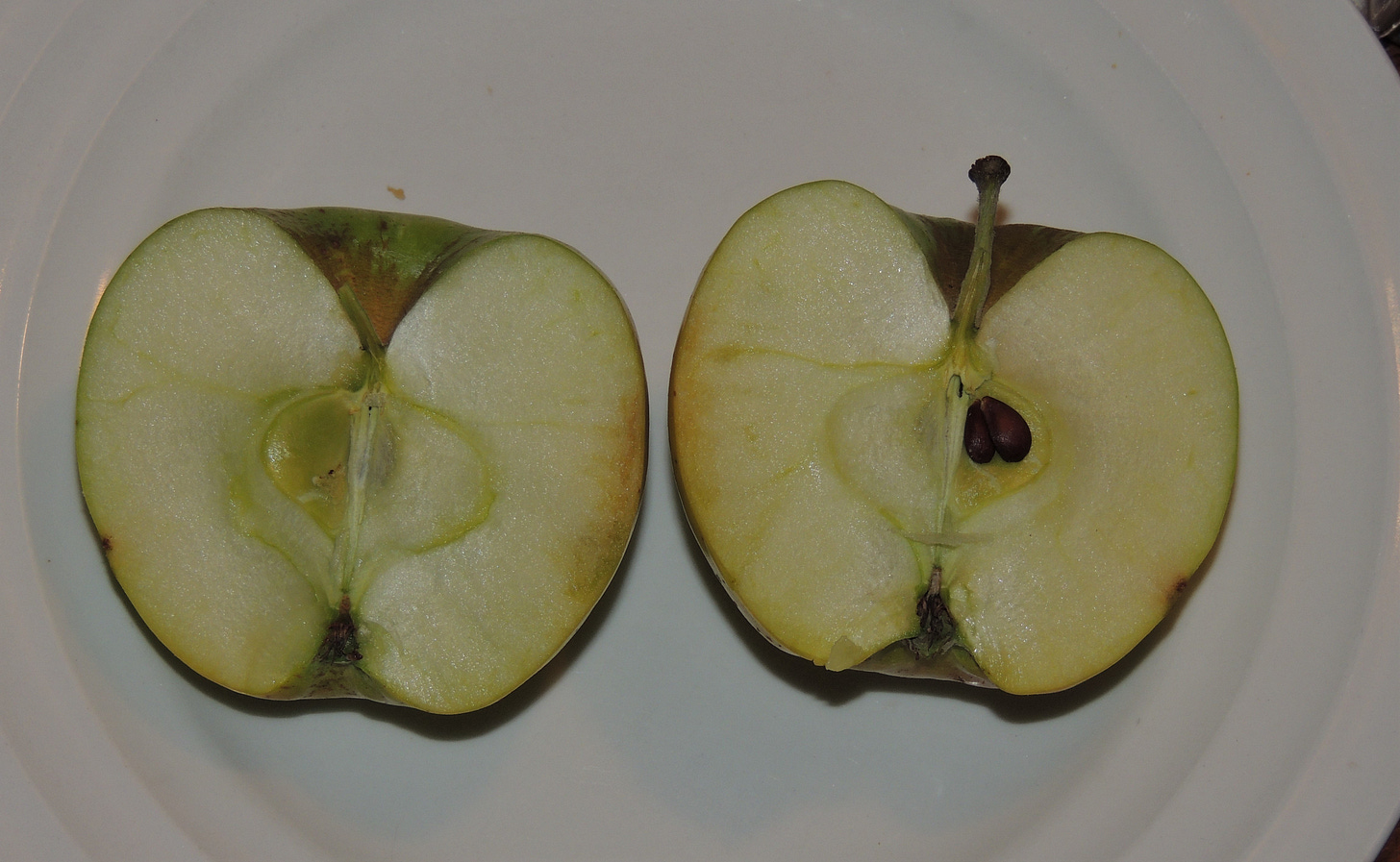

While caring for our baby wild apple trees (grown from seed here in our garden) is something I am very excited about, I am even more excited to announce that one of the two Malus sieversii seedlings we had purchased from the Cold Hardy Tree Nursery in bare root form (2020) produced their first blossoms this spring (which I hand pollinated) and have now produced our very first Malus sieversii fruit grown in Canadian soil! We were very happy with the bareroot specimens we received from Cold Hardy Tree Nursery, they were some of the better quality bareroot trees I have ordered. Their staff is also knowledgeable and willing to help troubleshoot.

I find the flavor of our first 'new apple variety' to be tangy, bright, vibrant with a sweet background flavor and a hint of nuttiness . I also find that is has a refreshing crisp and dense texture similar to Fuji apple flesh. My wife says it has subtle notes reminiscent of Macintosh, Ambrosia and Granny Smith and she thinks it pairs great with white cheddar, swiss cheese or monterey jack. She also finds that it goes well diced up in a pecan salad and/or enjoyed with white wine. I think they would make great hard cider due to the rich tannins and organic acids and would also make for a lovely pie apple. We have yet to name the new variety. I think I shall enjoy a few more fruit before settling on a name :)

We will plant the seeds we have saved from our first wild apple harvest and scale up our food forest gardening endeavors with a second generation Canadian wild apple trees (which will be even more well acclimatized and disease resistant then the first generation).

Update: Jan, 11th, 2023

Oops! I forgot I had a few Malus sieversii seeds stratifying in the fridge and stumbled across them the other day to find they had germinated!!

I carefully put those precious little living libraries of infinite genetic diversity (holding the potential for creating countless new apple varieties that are disease resistant and truly acclimatized to our local growing conditions) in some potting mix with, compost, diluted EM1 and some mycorrhizal spores and the first one pushed through the soil a couple days ago!

*Update February, 2023

Our malus sieversii seedlings are coming along nicely and beginning to exhibit some unique traits (such as anthocyanin expression in the leaves of some seedlings). This variation in the traits of only 11 seedlings is making me very excited to see how different the blossoms and fruit they produce will be in a few years.

I am holding the vision and intent that we will get some deep pink blossoms and brightly colored anti-oxidant rich fruit produced by one or more of the 11 new wild apple apple varieties we have started from seed.

*Update Feb 15th, 2023:

I am beginning to be able to observe additional unique characteristics that are beginning to become more and more pronounced in our malus sieversii seedlings. Aside from varying degrees of anthocyanin expression in the leaves I am also now seeing different shapes of leaves as more mature leaves begin to form.

Based on my past observations of the leaves of various crabapple varieties compared to domesticated apple varieties I estimate that these leave patterns may be indicative of specific characteristics that will be expressed in the fruit. I am looking forward to testing out this hypothesis in future years.

While I was intending on stratifying/preserving them in the fridge and then placing them in the living soil outside in the late fall (so they would naturally wake up in the spring, like the other ones will) as I harvested the apples these particular seeds came from too early in the season to be able put them directly in the soil, but given they have woken up now I will grow them inside until I can safely acclimatize them outside with warmer spring weather.

I am super excited for all the possibilities this opens up for future food forest design projects in Canada as these wild apple (Malus sieversii) trees can live to be 300 years old+ (becoming 60 feet tall) which could provide a very unique and productive canopy tree for a temperate food forest.

These were some of about 33 seeds I managed to extract from the very first fruit that our Malus sieversii tree (which was grown from seed here in our south Ontario garden) produced in 2022.

I will be adding the resulting seedlings to several food forest projects we are working on once they are mature enough and I am really excited about all the genetic diversity and abundance they will bring to those projects in future years (and hopefully for future generations).

I think I will be doing some selective breeding in future years where I introduce the pollen of anthocyanin rich fleshed apple varieties (such as “Mountain Rose”) in an effort to increase the antioxidant content and visual appeal of the fruit produced our future generations of wild apple trees. Canadian wild apple forests here we come!

Update September 3erd, 2023

We are about half way through our second year harvest on our larger tree (which was grown from seed) and the tree is still loaded with fruit!

Check it out!

I have noticed that our new apple variety has very pronounced lenticels (the small white dots on the skin of the apple that allow for the apple to breathe) and they remind me of when the star filled sky is transitioning into a blush colored sunrise.

Thus, we have decided to name this new variety Starlight Blush.

I did a first harvest of some that were early to ripen up a couple days ago and extracted the seeds to send out in the mail to a bunch of permaculture designers, food forest creators and passionate gardeners who expressed an interest in giving them a place to spread out their roots and achieve their true potential. I am pretty excited to have shared second gen (“Turtle Island” grown) malus sieversii seeds to people all over Canada and the US. It makes my heart glad to imagine towering wild apple trees growing in varied forest climates, nurturing many future generations and providing habitat and food for non-humans too.

You can count the seeds in a single apple, but you cannot count the apples in a single apple seed.

An Addendum On Growing Wild Food and Medicine Plants

Undomesticated ancient apples are not the only progenitor species to modern day favorite crops we are growing. We are working to acclimatize other ancient wild relatives to our favorite staple crops and superfoods such as Wild Chilis (Capsicum annuum var. glabriusculum), Wild Tomatoes (Solanum pimpinellifolium), Wild Goji Berries, Wild Echinacea (E. purpurea), Wild Tulsi aka “Holy Basil” (Ocimum tenuiflorum and Ocimum gratissimum) and Wild Green Tea Bushes (Camellia sinensis). I will explore the health benefits and synergistic potential of planting these crops together in the garden (or a food forest) in future posts. This is something I am passionate about not just because these undomesticated food and medicine plants will offer unique flavors and beauty to our garden but also, as state above, gathering, saving and growing wild seeds from the progenitor species of our favorite domesticated crops is critical in protecting our food supply from crop diseases, insect pests, catastrophic droughts and erratic weather.

The ancient ancestor of all modern tomatoes we are growing (Solanum pimpinellifolium, commonly known as the currant tomato) is showing great promise in disease and cold resistance (now in it’s third generation in our garden). It is a wild species of tomato native to Ecuador and Peru but naturalized elsewhere, such as the Galápagos Islands. Due to agricultural development, the wild currant tomato is becoming less prevalent in the native range of northern Peru and southern Ecuador so I hope to give it a sanctuary here in Canada and share seeds to keep the ancient lineage alive. These progenitor species have a vast potential for genetic variation for breeding new varieties that have disease resistance and other favorable traits.

The Green Tea Plants (Camellia sinensis) we are growing were grown from seed that a friend sent us from the Wuyi Mountains (in the northern part of the Fujian province in China). The seed type is considered as a "Quntizhong" (qúntǐzhǒng) or Heirloom tea cultivar (referred to by the locals as qízhǒng (奇种) or “surprise bush”). This name is said to express the unpredictable variation in the plants’ characteristics from one generation to the next. In a similar fashion to Malus sieversii, that is a common attribute with the undomesticated tea plants that grow in the Wuyi Mountains as many are a mix of highly diverse wild strains that cross breed (which are grown from seed and not cloned/asexually propagated as most tea plants are now a days).

If you enjoyed the content of this post and would like to support my work further you can learn more about my upcoming book here and pre-order a copy here. The book contains recipes, forest gardening techniques and info on the history, present day relevance and health benefits offers by other wild progenitor species of our modern day domesticated favorites

Hi! Loved reading this article as I have been living in Kazakhstan for almost ten years now and am familiar with some

of these apples, and have eaten quite a few. Every spring one of my favourite things is to walk into the apple groves when the trees are in blossom. As we have a property in Naramata, BC and would like to plant some Alma-Ata apples, this was an excellent connection for us. If you want to contact me, send an email to: DMMaisonneuve@gmail.com

Beautiful and informative! I found you through Caitlin's Substack. I harvested six bags and two bins of my Mutsu yesterday, feeling like a squirrel hiding nuts as I put most into deep storage in my fridge for the winter. As my friend said, some were as big as a newborn's head! This year my daughter's fiance got the coddling moth trap up in time and I've lost almost none, but I gave him two bags with slight blemishes for his passion, which is cider. Thanks for giving me so much background!