Tiny Beings Offering Immense Wisdom

In this article we look through my lens to learn from our elders in the ancient kingdoms of moss and lichen, listening for what whispers they offer to guide us on our path forward

Mosses and Lichens are pioneers and alchemists. These patient, generous and resilient beings were among the first beings to call the land home on the body of our Mother Earth. They engaged in the sacred task of transforming rock into soil, transforming the bare bones of Earth into flesh (through gathering starlight and focusing it into their alchemical gifts) to co-create the matrix from which all land dwelling life would one day draw sustenance (soil).

Moss

The way of moss is an honorable path, a courageous path, a peaceful path and a path of reciprocity. Looking at the way moss lives one might describe her as walking the path of what humans call Satyagraha.

I feel this ancient and resilient form of life has much to teach humanity with her humility, perseverance, patience, grace, determination and symbiosis with her fellow beings.

“There is an ancient conversation going on between mosses and rocks, poetry to be sure. About light and shadow and the drift of continents. This is what has been called the "dialect of moss on stone - an interface of immensity and minute ness, of past and present, softness and hardness, stillness and vibrancy, yin and yan.”

― Robin Wall Kimmerer, Gathering Moss: A Natural and Cultural History of Mosses

“Infrared satellite imagery, optical telescopes, and the Hubbell space telescope bring vastness within our visual sphere. Electron microscopes let us wander the remote universe of our own cells. But at the middle scale, that of the unaided eye, our senses seem to be strangely dulled. With sophisticated technology, we strive to see what is beyond us, but are often blind to the myriad sparkling facets that lie so close at hand. We thing we're seeing when we've only scratched the surface. Our acuity at this middle scale seems diminished, not by any failing of the eyes, but by the willingness of the mind. Has the power of our devices led us to distrust our unaided eyes? Or have we become dismissive of what takes no technology but only time and patience to perceive? Attentiveness alone can rival the most powerful magnifying lens.”

― Robin Wall Kimmerer, Gathering Moss: A Natural and Cultural History of Mosses

Moss is resilient and can (being capable of withstanding minus 40C and colder) and still bouncing back.

Mosses (and Lichens) are a protectors and community builders.. helping protect ancient residents of the forest (preventing organisms that would develop a pathogenic relationship with the trees from taking hold via exuding mild acids that act like an exfoliant and probiotic tree defense system) that are healthy, existing in sybiosis with young trees and old growth trees alike.

Mosses and Lichens also serve as community builders and assist in expediting the process of turning sick or dead members of the forest back into soil that can nurture new life (via living on the surface on the dead trees/stumps and helping make conditions ideal for their fungal allies to help break the wood back down into soil). Mosses and Lichens are stewards of life and alchemists that help the ancient residents of the forest to go back to the Earth when it is their time, helping make the way for new life.

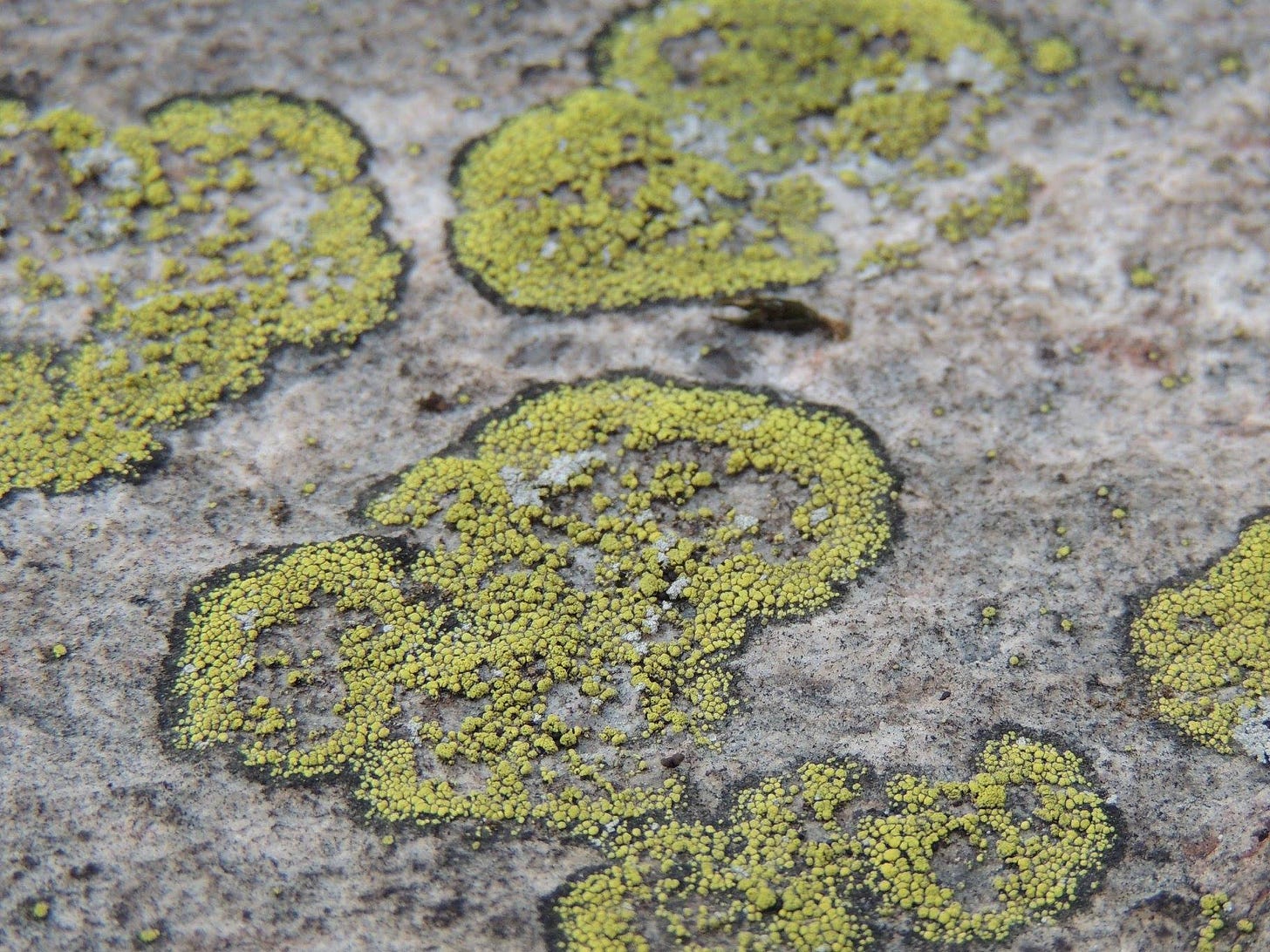

Moss and Lichen make will often create ‘ecosystems within ecosystems’ (via colonizing otherwise inhospitable objects such as large boulders and erratics (such as the one shown in the pic below) helping lay the foundation for soil to accumulate and other plants and organisms to also set up shop (increasing the bio-diversity and productivity of the forest ecosystem).

Moss and Lichen make vertical ecosystems possible, adding another layer of beauty, medicine, stability and food to the forest landscape.

Living on forest cliffs, desert boulders, mountain tops and rugged ocean shorelines.. mosses and lichens are masters at weathering the elements (while also contributing their unique gifts to enrich each of those ecosystems).

“In indigenous ways of knowing, it is understood that each living being has a particular role to play. Every being is endowed with certain gifts, its own intelligence, its own spirit, its own story. Our stories tell us that the Creator gave these to us, as original instructions. The foundation of education is to discover that gift within us and learn to use it well.”

― Robin Wall Kimmerer, Gathering Moss: A Natural and Cultural History of Mosses

Highly efficient, humble and resilient ancient organisms like moss offer us wisdom on how we might become more resilient in challenging conditions, sequester life giving water and co-exist symbiotically along side many other beings.

Besides offering us wisdom moss also offers food to those in need and medicine to those that need healing. Sphagnum moss (and various lichens) have been used since ancient times as a dressing for wounds and now modern science has discovered their may be a good reason for this.

Amongst the higher animals, the vertebrates, moss is consumed by bison, reindeer (principally in the high arctic regions), lemmings in Alaska (up to 40% of their diet) and many species of bird (geese, grouse).

Moss is not very nutrient dense but it can help you get some nutrients (like protein and some minor vitamins) in a survival situation. For more info on moss as a survival food you can go to this link.

Because of its absorbent and antiseptic qualities, sphagnum moss was extensively used for dressing wounds and as a forerunner of disposable nappies (diapers) for babies.

In ancient times, Gaelic-Irish sources wrote that warriors in the battle of Clontarf (where the the Vikings teamed up with some turncoats and were carrying out a large attack on Gaelic Ireland) the native Gaels used moss to pack their wounds.

Moss was also used by the peoples indigenous to Turtle Island, who lined their children’s cradles and carriers with it as a type of natural diaper.

It continued to be used sporadically when battles erupted, including during the Napoleonic and Franco-Prussian wars. But it wasn’t until World War I that allopathic doctors acknowledge/realized the plant's potent medical potential.

Sphagnum moss has antiseptic properties. The plant’s cell walls are composed of special sugar molecules that “create an electrochemical halo around all of the cells, and the cell walls end up being negatively charged,” Kimmerer says. “Those negative charges mean that positively charged nutrient ions [like potassium, sodium and calcium] are going to be attracted to the sphagnum.” As the moss soaks up all the negatively charged nutrients in the soil, it releases positively charged ions that make the environment around it acidic. For wounded humans, the result is that sphagnum bandages produce sterile environments by keeping the pH level around the wound low, and inhibiting the growth of bacteria.

Certain species of moss also contain relatively large quantities of a polysaccharide that works as an immunomodulator, regulating the immune system through stimulating cells such as lymphocytes and macrophages, which fight infections. Other moss species offer medicinal benefits for treating nausea, inflammation, and muscle cramps.

For more information on the many medicinal uses of Moss you can look here, here, here, here, here, here and here.

Lichen

Lichens are a prime example of a symbiotic, or mutually-beneficial relationship between two or more species.

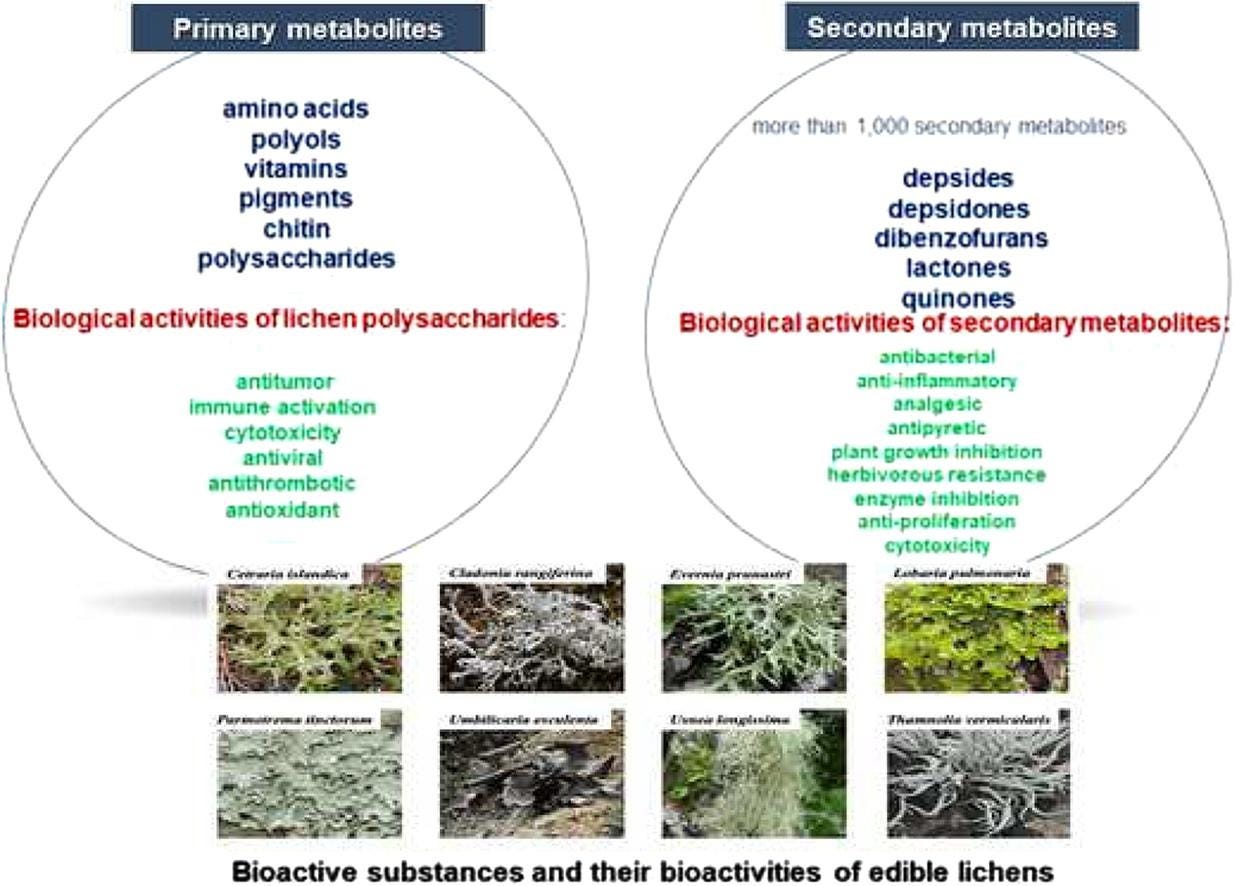

The lichen symbiosis is composed of a fungus (the heterotroph) and an algae and/or cyanobacteria (the autotroph). In the lichen, the autotroph absorbs photons from the sun and stores this energy in the chemical bonds of molecules. In turn the fungus, the heterotroph, takes those molecules and uses the stored solar energy to form more molecules, creating a diverse array of pigments, chemicals, and proteins.

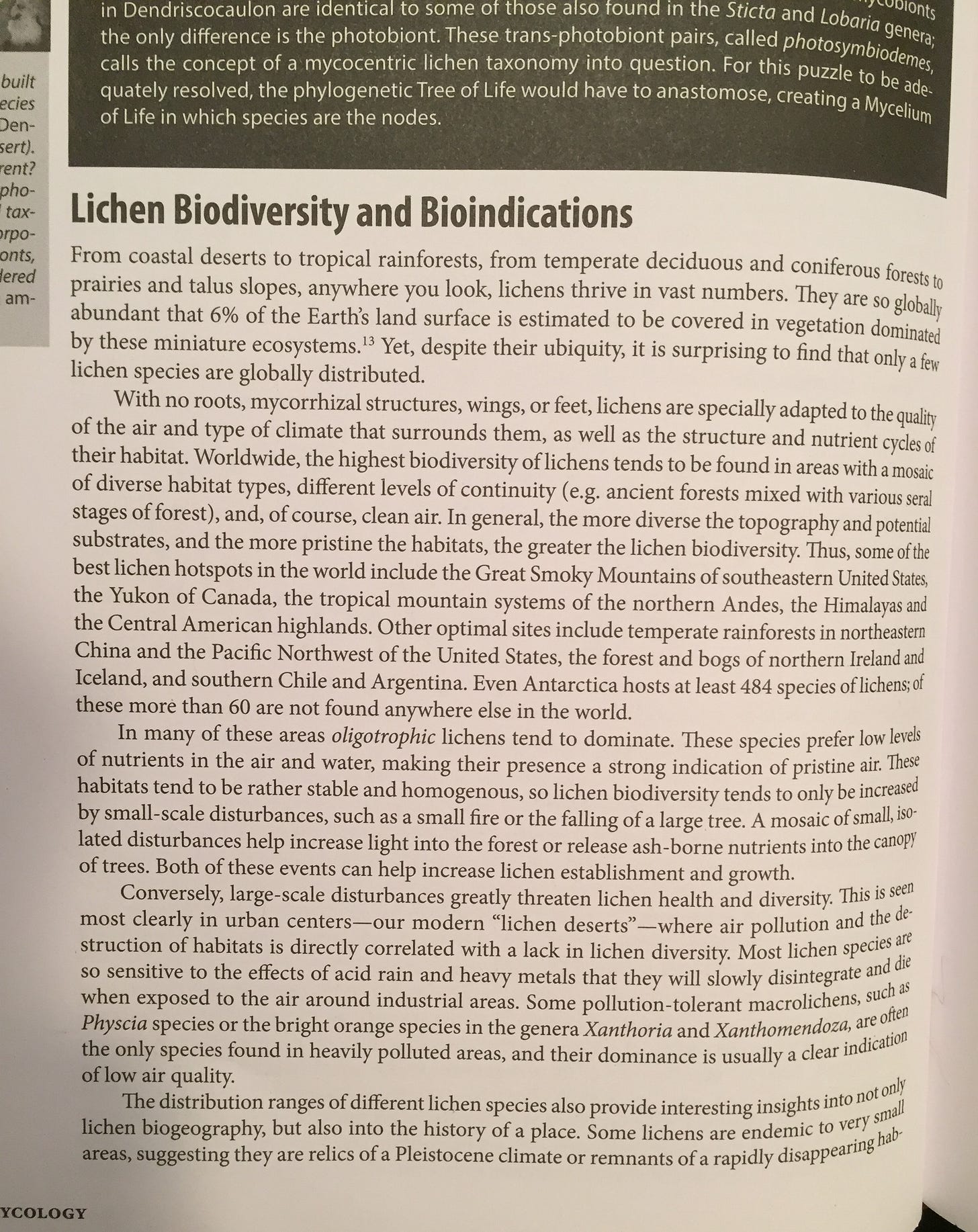

They offer us wisdom about humility, patience and the value of forging alliances with our fellow beings (rather than making enemies/competing). Lichen are known for being able to survive in some of the most extreme climates on earth, and it’s estimated that they cover roughly 6% of the Earth’s surface. They’re capable of growing at high elevations or at sea level, and they can be found on nearly any surface: covering rocks, bark, walls, and hanging in thin air. Researchers from the German Aerospace Center found that some lichen are even hardy enough to survive on Mars.

The wisdom of lichen’s way of being is self-evident as they thrive in many places where humans cannot and their lineage on Earth is an extremely far reaching and ancient one.

Lichens have been used for medicinal purposes throughout the ages, and beneficial claims have to some extent been correlated with their polysaccharide content. Lichen polysaccharides which can be isolated in considerable yield such as the -glucans, -glucans, and galactomannans are generally expected to be of fungal origin. Several lichen species, such as Cetraria islandica and lobaria pulmonaria, have been used in traditional medicine since ancient times, to treat a variety of illnesses. All lichen species investigated so far produce polysaccharides in considerable amounts, up to 57%, and many of them have been shown to exhibit antitumour, immunostimulating, antiviral activity as well as some types of biological activity.

Usnea, also known as “old man’s beard”, is a type of lichen that grows on the trees, bushes, rocks, and soil of temperate and humid climates worldwide. It has long been used in traditional medicine. The ancient Greek physician Hippocrates is believed to have used it to treat urinary ailments, and it’s regarded as a treatment for wounds and inflammation of the mouth and throat in South African medicine. Modern science has confirmed that usnea is an immune system optimizer and has powerful antibiotic and antiviral properties. Like many other lichens and mosses “old man’s beard” can be made into a poultice to be applied directly on a wound, which is good to know when you are out hiking in the woods or in a survival situation.

Many of the traditional dyes of the Scottish Highlands were made from lichens including red dyes from the cudbear lichen, Lecanora tartarea,[1] the common orange lichen, Xanthoria parietina, and several species of leafy Parmelia lichens. Brown or yellow lichen dyes (called crottle or crotal), made from Parmelia saxatilis scraped off rocks,[2] and red lichen dyes (called “corkir”) were used extensively to produce tartans.

You can find more info on accessing the medicinal gifts offered by Lichens, here, here, here, here and here.

You can find more info on Lichen as food here, here, here, here, here, here and here.

“Lichens are expressions of pure joy. Their variety of color, morphology, chemical constituents and inexhaustible capacity for adaptability is proof that the living world is not purely utilitarian. Lichens remind us that life is art and that deeply integrated into one’s environments is the most refined expression of that art. Lichens paint the rocks of the desert with living murals, drape the temperate forest with lace ribbons and thrive in the harshest climatic conditions. From antarctic to tropical systems, from rainforests to deserts, lichens are every-present, showing us a way of fungal being that is always exposed, always present.

Humbly, they slowly grow by crystallizing sunlight and vapor into delicate but resilient symbiotic systems. Inside the ecosystem of a lichen are most of the primary components of life: fungi, bacteria, algae, and cyanobacteria, all living in a discrete synergistic system that can rarely be synthesized in virta but can withstand the extreme conditions of outer space.

This symbiosis of fungus and algae is thought to date back to the first ancestors of terrestrial life. As landforms diversified and developed, as mountains rose defiantly and weathered into soft hills, lichens have been patiently watching from their perches. Some contemporary lichens are over 5,000 years old---relics from a distant age. Lichens are the beholders of stores on landscapes and climate, if one takes the time to witness them clearly

Through their slow and ancient nature leads to lichens beings lost in the larger members in their ecosystems, these fascinating beings are not static. Rather, they perform numerous mutualistic roles with bacteria, insects, rodents, ungulates, and humans. And there are four main reasons that humans work with lichens: as medicine, as a natural dye source, to monitor environmental health, and to study ecosystem biodiversity and dynamics.” Lichens show us what is possible in the dimension beyond the divides, something emergent, greater than the sum of its parts, something whole. Medicine for our times.”

- Nastassja Noell (from the “Radical Lichenology” chapter of “Radical Mycology-A Treatise on Seeing and Working with Fungi”)

“Six lessons I have learned from our neighbor the lichen.

Always be present. Unlike their mushroom brethren—who disappear under the ground for long periods of time and only emerge to fruit in ideal conditions—lichens are always present. They live on the surfaces of twigs, stones, and soil; in winter, summer, drought, or monsoon. Like a lichen in a storm, you can weather what comes at you in life. In challenging moments and joyous ones, bear witness to the emotions moving through you. This is an important step for healing our eco-cultural wounds and for growing into our best selves.

Engage in subtle change. Lichens are emergent properties, meaning that they are more than the sum of their parts. Together, they create a dynamic system, doing things no partner could do alone. Forest ecosystems are emergent properties, as is your consciousness and our communities and families. We’re constantly forming new emergent beings when we’re in relationship with others. How we choose to engage with each other shifts the shape and texture and feeling of these emergent beings. It’s a lot of responsibility. And yet, it’s the most subtle movements that create change. There lies the power. By subtly changing the way you interact with the world and all your relations, the emergent properties you are a part of change in fundamental ways. Its a simple and fundamental as asking “who” a plant is instead of “what” a plant is.

Celebrate differences. The entities in the lichen symbiosis are found throughout the tree of life, in numerous kingdoms and with both autotrophs and heterotrophs. Despite vast differences, the partners of a lichen symbiosis go beyond them, merging their differences together in ways that enable them to thrive in extreme conditions that most other forms of life cannot bear — deserts, alpine, Antarctic, tops of trees, seaside rocks and can even survive the extreme radiation and vacuum pressure of outer space. Just like how our right and left brain perform unique functions and contribute unique strengths, what if we were to merge our dualities together and see how our differences can collaborate towards a better outcome for everyone?

You are place. “Lichens are place,” is a saying that lichenologist Trevor Goward explores in his series of essays, “Ways of Enlichenment: Twelve Readings on the Lichen Thallus.” Lichens have no roots to reach out and acquire nutrients. Their bodies crystallize from the air, rain, sunlight and the substrate they grow on. So, the lichen species of each place reflect the conditions of that place. An ancient forest has different lichen species than a 100 year old forest, while an urban area hosts a limited number of pollution tolerant species. We humans are not so different. We are also influenced by the environments we live in, grow up in, and spend time in. Our bodies extend beyond our arms and legs and head and feet. We are the spaces we sit in, walk in, drive in. We are shaped by the tools we use, foods we eat, water we drink, air we breathe. Our bodies are place. Embracing this means caring for the places around us and connected to us as we care for ourselves.

Grow slowly. Lichens grow an average of 2 mm a year. Some grow a bit faster. That’s why most herbalists collect only windfallen lichens for making medicine. Your palm can hold decades of growth by a lichen that weighs less than a paperclip. Slow growth may be contrary to our hyper-extractive capitalist system that we’re all caught in. However, perhaps slow growth, thoughtful growth, intentional growth, is exactly what we need to grow strong and resilient.

Rest. When lichens go into a dormant state, they don’t enter entropy or decay and they don’t die. They simply go into an intentional pause where all bionts (symbiotic partners) are supported. In deserts, lichens sometimes go dormant for years; one raindrop might be all they need until the next rainy season. The big question is, if we’re not producing and growing as a society, what are we doing? Can we imagine spending more time enjoying each other and ourselves, being present for the mysteries of life unfolding, using only what we need to thrive, sharing resources, skills, land, and seeds? What kinds of songs and stories and imaginative play might we co-create if we shifted out of productive growth-oriented mode into something slower, less extractive, more contemplative?”

- Nastassja Noell (from How to Be a Lichen)

You can usually tell what kind of algae a lichen has just by color alone. When a lichen is dry, its color is usually gray or colored like the fungal cells on the upper cortex. When a lichen is wet, those cells become transparent, and the algal cells underneath get a chance to show its vibrancy. These colors and structures often have a specific function (such as protecting from temperature extremes or reducing water loss via evaporation). Colors are a byproduct of the complex chemistry of lichen tissues.

The fungal skin of lichens also prevents water loss to the algae below via its dense compacted thread structure.

Lichens develop minuscule branches and grow into dense curling thickets a few inches high. Their outer skin is formed by the compacted threads of the fungi and is sufficiently impermeable to prevent the loss of water from the partnership; beneath are the algal cells, kept moist and protected from harmful ultra-violet radiation by the fungal skin; and below them, in the centre of the structure, there is looser tissue, also provided by the fungus, where food and water is stored.

Here is some additional practical and educational info about lichen, their role in eco-systems and how we can team up with them in our ecosystem regenerating efforts.

We can emulate the genius example of symbiotic and synergistic design (that is exemplified in lichen) in how we build homes and design food production systems.

This leads me to another overlooked potential that is worth exploring, which is the propagation and cultivation of mosses and lichens as part of a food forest design. Given lichens are eco-systems in and of themselves (and given they can provide medicine, food, dying materials and symbiotic partnerships with trees) they essentially open up an entirely new dimension of fractal food cultivation (in which you are designing an eco-system that contains trees and then also encouraging ecosystems to flourish on the surface of the tree’s bark as well). Ecosystems embedded within ecosystems, offering increased resilience for all members and increased outputs of food and medicine for the human food forest stewards.

You can find examples of how we might apply the wisdom of our elders in the Lichen kingdom in our biomimmicry designs, here, here, here, here, here, here, here and here.

In closing I will share a quote from another quote from Gathering Moss that I feel not only offers much truth with regards to moss and lichen, but also wisdom for life in general.

"..A Cheyenne elder of my acquaintance once told me that the best way to find something is not to go looking for it. This is a hard concept for a scientist. But he said to watch out of the corner of your eye, open to possibility, and what you seek will be revealed. The revelation of suddenly seeing what I was blind to only moments before is a sublime experience for me. I can revisit those moments and still feel the surge of expansion. The boundaries between my world and the world of another being get pushed back with sudden clarity, an experience both humbling and joyful.

The sensation of sudden visual awareness is produced in part by the formation of a “search image” in the brain. In a complex visual landscape, the brain initially registers all the incoming data, without critical evaluation. Five orange arms in a starlike pattern, smooth black rock, light and shadow. All this is input, but the brain does not immediately interpret the data and convey their meaning to the conscious mind. Not until the pattern is repeated, with feedback from the conscious mind, do we know what we are seeing. It is in this way that animals become skilled detectors of their prey, by differentiating complex visual patterns into the particular configuration that means food. For example, some warblers are very successful predators when a certain caterpillar is at epidemic numbers, sufficiently abundant to produce a search image in the bird’s brain. However, the very same insects may go undetected when their numbers are low. The neural pathways have to be trained by experience to process what is being seen. The synapses fire and the stars come out. The unseen is suddenly plain.

At the scale of a moss, walking through the woods as a six-foot human is a lot like flying over the continent at 32,000 feet. So far above the ground, and on our way to somewhere else, we run the risk of missing an entire realm which lies at our feet. Every day we pass over them without seeing. Mosses and other small beings issue an invitation to dwell for a time right at the limits of ordinary perception. All it requires of us is attentiveness. Look in a certain way and a whole new world can be revealed."

― Robin Wall Kimmerer (Gathering Moss: A Natural and Cultural History of Mosses)

I hope this article inspires you to slow down and look closely at our smaller, more humble and often overlooked elder species and use your pattern recognition, intuition and deductive reasoning to unlock the wisdom they offer us. Each being (no matter how small, inconspicuous, or seemingly simple offers it’s own unique gifts. It is through learning to recognize those gifts within others (and within our selves) and then applying them for the benefit of all beings that we can unlock Humanity’s dormant potential to become a regenerative and co-creative force on Mother Earth. Perceiving, unlocking, and applying those gifts is a sacred task that each of us is called to engage in now.

May your courage, humility, patience and choice to see with an open heart lead you to unlock your many gifts within and perceive them in abundance in the beings you share this world with. May this path to perceive and share our many gifts lead to a time of abundance, lasting fulfillment, innovation, ecological regeneration and spiritual metamorphosis.

So it is, and so it shall be.

This was a great article. Absolutely loved it and learned so much. Thank you.

wow wow wow. this is extraordinary, beautiful and the pictures out of this world 🐒 thank you