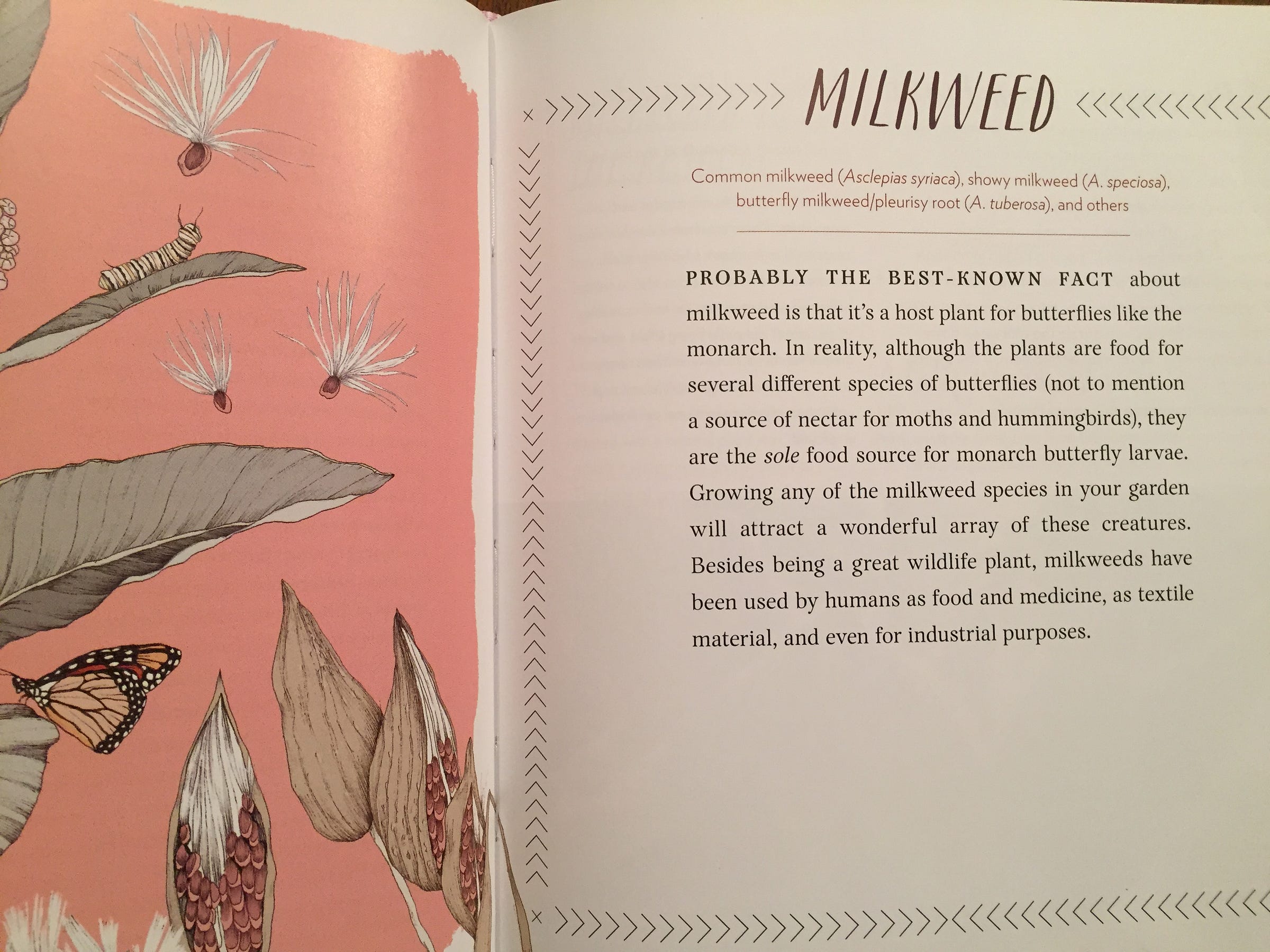

Milkweed (Asclepias syriaca)

Exploring the many gifts offered by Common Milkweed the in the context of Food Forest Design. This is Installment #15 of the Stacking Functions in the Garden, Food Forest and Medicine Cabinet series.

This post serves as the 15th post which is part of the Stacking Functions in the Garden, Food Forest and Medicine Cabinet : The Regenerative Way From Seed To Apothecary series.

The fields of Milkweed pods have opened and are releasing their billions of gifts upon the autumn wind... given freely to the rich, receiving and grateful Earth below (and to those that would receive them with open arms, metaphorically speaking).

These gentle clouds of seeds move with purpose now in the late days of October (here at the 42nd parallel). Carried faithfully by their velvet soft starburst shaped sails of silken fibers, these armadas of life are dancing like ballerinas on gentle breezes, moving swiftly like shooting stars on cool gusts of autumn wind and floating effortlessly on updrafts of warmth they imbibe from the afternoon sunrays on still days.

These seeds speak to me of the grace and genius of Mother Earth and the Creator of all things that set these magnificent beings into motion.

Milkweed (as a being) inspires my imagination, teaches me to move with more grace and patience, as well as invites my heart to open when I feel like all is lost.

Her effortless and irrepressible way of expressing herself reminds me to never give up and to know that forces and divine will beyond the jurisdiction of human arrogance weave artistry, hope and beauty into all things and places (whether some humans like it that way or not).

Beyond the spiritual and intellectual I also feel that we should begin to recognize milkweed's many medicinal and nutritional gifts as well. That is what the article below is about.

Many people only see Milkweed as the famous preferred food for Monarch Butterflies, but her gifts are myriad and she also offers many of them to help nourish our human family and empower us to live more regeneratively. I will now invite you to explore the many ways in which developing a reciprocal relationship with milkweed can empower us to stack many functions in the garden, the food forest, the kitchen and in the medicine cabinet.

Common Name: known as Ninwanzh by the Potawatomi people, commonly called common milkweed, butterfly flower, silkweed, silky swallow-wort, and Virginia silkweed

Family: Asclepiadaceae

Parts used for food:

Unopened flower buds - cooked. They taste somewhat like peas. They are used like broccoli[5].

Flowers and young flower buds - cooked. They have a mucilaginous texture and a pleasant flavour, they can be used as a flavouring and a thickener in soups etc[6][7][8]. The flower clusters can be boiled down to make a sugary syrup[9][10]. The flowers are harvested in the early morning with the dew still on them[11]. When boiled up they make a brown sugar[11].

Young shoots - cooked. An asparagus substitute[9][12][13][6][14][11][5]. They should be used when less than 20cm tall[15].

Young seed pods 3 - 4 cm long, cooked[9][13][6][10]. They are very appetizing. Best used when about 2 - 4cm long and before the seed floss forms, on older pods remove any seed floss before cooking them[10][15]. If picked at the right time, the pods resemble okra[5].

The sprouted seeds can be eaten[5].

Parts used for Medicine: Roots (as a decoction, tincture or poultice), The leaves and/or the latex are used in folk remedies for treating cancer and tumours. The milky latex from the stems and leaves is used in the treatment of warts.

Constituents:

Cardiac glycosides: cardenolide type (afroside, asclepin, asclepiadin, calactin, calotropin, gomphoside, syriogenin, syrioside, uscharidin, uscharin and uzarigenin).

Flavonoids (kaempferol, quercetin, rutin and isorhamnetin)

Amino acids (choline)

Phenolic acids (caffeic & chlorogenic acid)

Carbohydrates (glucose, fructose and sucrose)

Triterpenes (a-amyrin and bamyrin, lupeol, friedelin, viburnitol)

Volatile oil

Resin

Latex (isoprene polymers)

Cardenolides

Alkaloids

Nutrition:

Protein (Milkweed seed contains 21% oil and 30% crude protein (dry basis)

vitamin C

calcium

potassium

silica

zinc

iron

Medicinal actions:

Antispasmodic

Cardiotonic

Carminative

Diaphoretic

Diuretic

Laxative

Expectorant

Nervine relaxant

Vasodilator

Pharmacology and Medicinal use:

Phytochemical studies on Asclepias species have identified many cardiac glycoside constituents. A as rule, cardiac glycosides inhibit the sodium potassium pump leading to a rise in intracellular calcium, which increases contractile force and speed of the heart muscle. A positive inotropic action (in vivo and in vitro) has been reported for asclepin, which was found to be more potent, longer acting and with a wider safety margin when compared with other cardiac glycosides (including digoxin). Asclepin was also reported to exhibit a more powerful activity towards weak cardiac muscle.

Low doses of extracts have been documented to cause uterine contractions (in vivo) and to exhibit estrogenic effects.

Flavonoids rutin and quercetin are cardioactive steroids.

Has its historical basis in the treatment of pleurisy to relieve the associated pain and ease breathing. The specific indications are shortness of breath, strong pulse, sweating/moist skin, acute pain that is worse with motion, and inflammation and catarrh of serous tissues.

Used primarily in chronic respiratory conditions (e.g. pneumonia, bronchitis), acutely for influenza (earliest stages), and intercostal diseases. Will induce perspiration (diaphoresis) and relieve suppressed expectoration while exerting an antispasmodic effect.

Considered to decrease arterial tension and creates mild sedation overall.

Pharmacy:

Decoction: ½ -1 tsp/cup , TID

Tincture: 1-3 ml (1:5, 40%), TID. 80 ml Weekly Max

Dried herb: 1-3 g, QD.

Note: traditionally given in small, frequent doses.

Cold Hardiness: 3 - 9

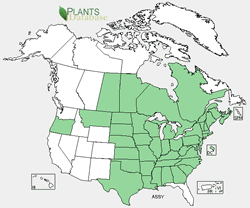

Native Range:

Eastern Turtle Island (aka North America) - New Brunswick to Saskatchewan, south to N. Carolina, Kansas and Georgia.

Growth Form:

Erect, unbranched, perennial herb spreading by deep thickened storage roots.

This milkweed grows to about 1.5 meters(5 feet) tall, usually occurring in clusters of stout stems. It has rhizomes and quickly forms colonies. The umbels bear large balls of pink to purplish flowers that have an attractive odor.

Reproduction:

Stalks typically produce 4-6 pods, each containing 100-425 seeds. The number of pods depends on the level of pollination (Morse and Fritz 1983). Normally, vegetative reproduction does not begin until the second or third year of life. An undisturbed plant in southern Ontario produced a colony of 56 shoots during its fourth growing season.

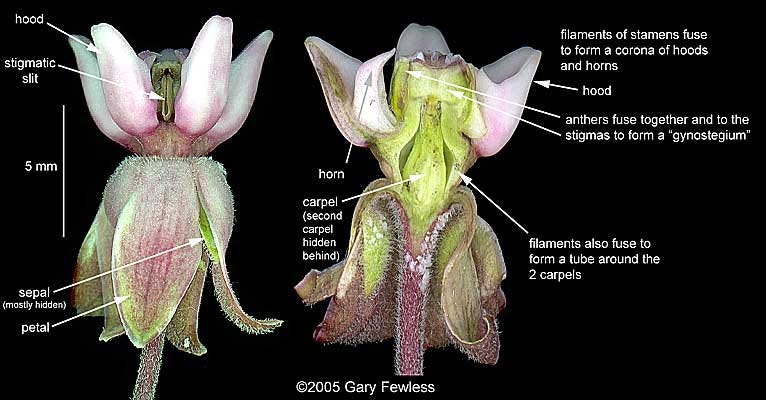

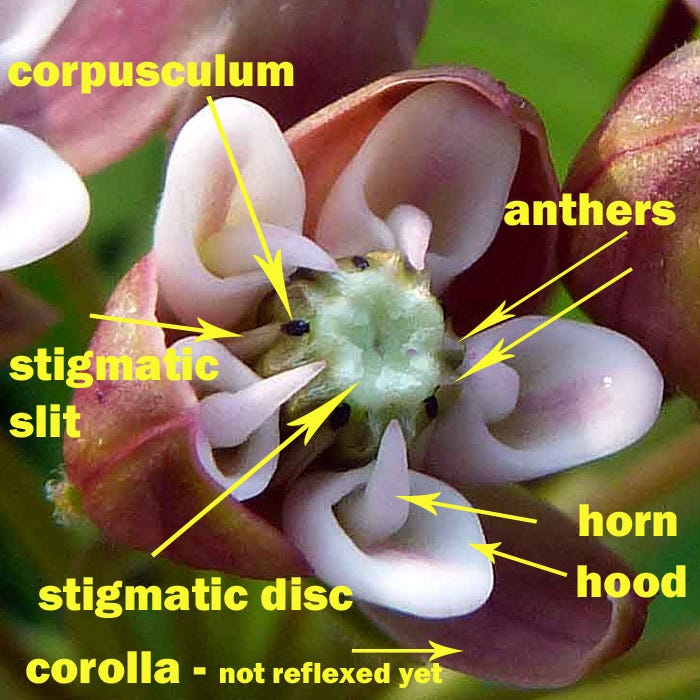

Three of the five stigmatic chambers of milkweed flowers transmit pollen tubes to one of the two separate ovaries, whereas the other two chambers transmit only to the second ovary. Milkweed flowers are long-lived and produce copious nectar, which flows from nectaries within the stigmatic chambers to fill the hoods, which serve as reservoirs. Nectar also serves as the germination fluid for pollen grains, but concentrations above 30% inhibit germination. Most milkweeds are genetically self-incompatible and express an unusual late-acting form of ovarian rejection

Habitat and Ecological Niche:

Origin and distribution: Common milkweed is native to eastern North America and occurs from Georgia to Oklahoma, and northward to southern Canada. It has been introduced into Europe and Japan and the Willamette Valley of Oregon.

This species usually grows in disturbed habitats, forest edges, roadsides, and open fields.

Flowering and Pollination:

Flowers of this species occur in umbellate cymes (a type of inflorescence) [46] with markedly different numbers of flowers per cyme and cymes per stem [42].

Asclepias syriaca (Common Milkweed) is a plant with a highly specialized pollination system that requires insect visitors to transport pollen, making it susceptible to pollen limitation and reduced fruit production if its flower period shifts.

Common milkweed is self-sterile and cross pollinated by insects, mostly bees and wasps. Bumble bees are primarily responsible for pollination by day, but moths pollinate at night.

Pollen generally is dispersed short distances to the same plant or to neighboring plants.

Nectar is abundant in common milkweed and represents the primary attraction for insect transport and germination of pollen. Although any given flower can function as either a pollen donor or a seed producer, on average, 58% of flowers in a cluster become pollen donors and the others receive pollen and can potentially produce pods with seeds. The majority of pollinated flowers abort, with very few producing mature seed pods.

Among the milkweeds, this species is the best at colonizing in disturbed sites. Within its range it can be found in a broad array of habitats from croplands, to pastures, roadsides, ditches and old fields. It is surprisingly rare in prairies in the Midwest being found mostly in disturbed sites within these habitats.

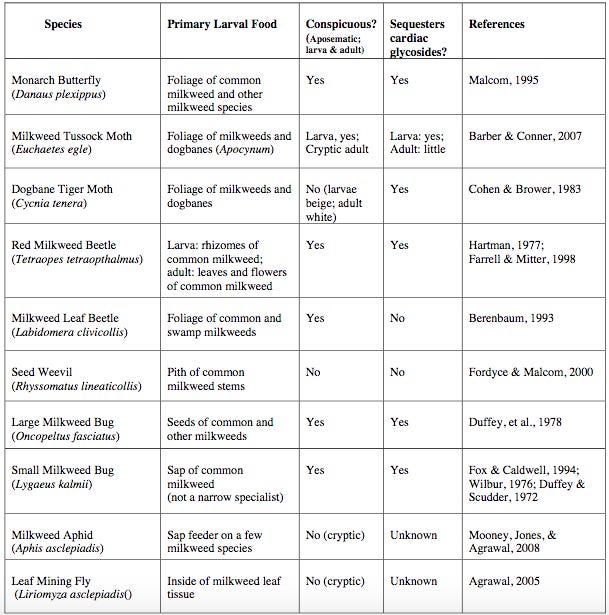

One striking feature of the common milkweed is that the entire life cycle of a number of insect species is tightly interwoven with it. There are at least 10 species of insects that feed only on common milkweed or other closely related milkweeds in the genus Asclepias (Agrawal, 2005; Price & Wilson, 1979; see Table 1 and Figure 11 A-G). These specialist species feed on milkweed rhizomes, shoots, leaves, flowers, or seeds. The most well-known of these is the monarch butterfly (Danaus plexippus). The adult butterfly lays its eggs on the leaves of common milkweed, the larvae live from its leaves and the milky sap the plants contain, and the adults drink from the flower nectar, although adults are not restricted to milkweeds.

We have already seen that common milkweed is an important part of the life of insects that feed on its nectar. Observing nectar feeders on common milkweed, Southwick (1983) identified representatives from 15 different orders of insects (and one hummingbird species). Nectar was taken mainly during the day but also during the night by a variety of nocturnal moths. But these nectar-feeding insects represent only a minority of the insects and other arthropods that interact with milkweed. In the late 1970s Dailey and his colleagues carried out surveys of bugs (Hemiptera) and beetles (Coleoptera) found on common milkweed (Dailey, Graves, & Herring, 1978; Dailey, Graves, & Kingsolver, 1978). Over the course of ninety days, they found 132 different species of beetles, 18 of which they considered common visitors, since they collected more than 50 specimens of each of these species. They collected 45 species of bugs, 5 of which were common visitors according to the same criterion. Milkweed teems with insect life.

For many insects, milkweed is certainly a small and transient part of their habitat—or speaking functionally, a minor part of their ecological niche. They may nibble on the leaves and flower buds, or drink some nectar and then move on to other plants. As predators they may, like the bug Phymata fasciata, hide in the thicket of milkweed stems, leaves, and flowers, waiting for their prey of flies and small wild bees. And then there are the milkweed specialists, which I will discuss below, that feed almost exclusively on milkweeds. So milkweed provides food and a microhabitat for a multitude of organisms. Its exuberant growth — in rhizomes, stems, leaves, flowers, fruits, and seeds — allows abundant insect life to orient around it. This, then in turn provides food for larger predators, so milkweed provides a strong ecological pillar to support biodiversity from insects up to larger animals.

Health Benefits of Common Milkweed (asclepias syriaca)

It provides several forms of safe nutrient dense food when cooked and eaten in moderation.

Nutrients present in cooked (and/or fermented) common milkweed:

Protein (Milkweed seed contains 21% oil and 30% crude protein (dry basis) )

vitamin C

calcium

potassium

silica

zinc

iron

A number of Native tribes have used the latex juice from the roots, plant tops, and stem for medicinal purposes. The Miwok people used the latex to remove warts. The Cheyenne made a decoction of the dried plant tops and used it as an eyewash to heal snow blindness. Cherokee, Delaware, and Mohegan peoples used it to make into a cough remedy. Today herbalists still use it for pleurisy, an inflammation in the lining around the lungs.

History and Cultural Relevance of Common Milkweed (asclepias syriaca):

This plant was recognized for it’s many nutritional, medicinal and material gifts by many different indigenous peoples of Turtle Island for thousands of years prior to European contact.

Indigenous Uses

Asclepias syriaca was used widely for a variety of purposes. As a food, people ate the boiled young sprouts like asparagus, cooked the unopened floral bud clusters and firm green fruits, as well as the tender leaves and upper stalks. The flowers and buds often thickened soups. Dried buds were stored for winter use. The latex was boiled and mixed with animal fat for a chewing gum. As a craft product, the fibers were used as cordage for bowstrings and fine sewing threads. Fibers from inside the large pods were used as a stuffing for pillows and sleeping pads. The milky juice was used as a glue. As a medicine, the plant supported treatment of venereal diseases, kidney and urinary dysfunction, rheumatism, and backaches. It was also used as a laxative, galactagogue, and contraceptive. Topically it was used to remove warts and treat bee stings, cuts, and ringworm.

Milkweed or Asclepias species were first collected and sent to Europe by French and English explorers in the 1500s and 1600s. In 1585, John White, the English artist who was part of the ill-fated Roanoke Lost Colony, illustrated Asclepias syriaca. The herbalist Gerarde included a description and illustration of Indian swallowwort that may have been a dogbane, but by the 1633 the illustration was that of Asclepias syriaca that was also call Apocynum syriacum. Around 1620, Louis Hebert, a French colonist and pharmacist in New France (Eastern Canada) sent seeds of Asclepias syriacum to Paris to investigate its medicinal properties. By 1635, Philip Cornut, a doctor and botanist in New France, described both Asclepias syriaca and Asclepias incarnada in Canadensium plantarum historia.

During WWII the fluffy seed pods were collected by school children to help with the war effort.

The fluff was used to fill life preservers, and it took 2 onion sacks full of the pods to make a single jacket. Enough was collected to make 1.2 million jackets…which gives you an idea of how much wild milkweed there must have been growing at the time.

These days, the seed pods are coveted by survivalists for all manner of uses from fire starting to filling field cots.

Mistaken identity (leading to fear in foraging books):

For years, wild food authors — usually parroting one another — claimed that the common milkweed was toxic (containing cardiac glycosides) and inedible (extremely bitter) without several rounds of boiling in successive changes of water. This misunderstanding was passed on for decades, eventually — thankfully — being proven false. Sam Thayer, in his seminal treatise The Foragers Harvest (2006), details this story at length. He surmises that the origin of this myth is Euell Gibbons’ 1962 wild food classic Stalking The Wild Asparagus, where the author likely conflated it with common dogbane. What a tragedy that Euell, and all those wild food enthusiasts who would follow after him, missed out on the wild-crafted cornucopia that this plant provides!

For more info read:

Functions In The Wilderness and in the Food Forest:

Ecological Functions:

Common milkweed plays an important role in supporting local pollinators, such as Apis wellifera (Western honeybee) and Bombus species (bubble bees). Common milkweed will produce large, tear-drop shaped pods in the fall. These pods can be harvested for many uses from insulation for clothing, to eating young (cooked pods) or for and the seed contained in mature pods used to propagate more A. syriaca plants.

Common milkweed is Nature's farmer’s market for insects. Over 450 insects are known to feed on some portion of the plant. Numerous insects are attracted to the nectar-laden flowers and it is not at all uncommon to see flies, beetles, ants, bees, wasps, and butterflies on the flowers at the same time. Hummingbirds also extract nectar. Its sap, leaves and flowers also provide food. In the northeast and midwest, it is among the most important food plants for monarch caterpillars (Danaus plexippus). Other common feeders are the colorful (red with black dots) red milkweed beetle (Tetraopes tetraophthalmus), the milkweed tussock caterpillar (Euchaetes egle) and the large (Oncopeltus fasciatus) and the small (Lygaeus kalmia) red and black milkweed bugs.

Milkweeds contain various levels of cardiac glycoside compounds which render the raw plants toxic to most insects and animals. For some insects, the cardiac glycosides become a defense. They can store them in their tissue which renders them inedible or toxic to other animals. Monarch butterflies use this defense and birds leave them and the caterpillars alone.

These plants are centers of biodiversity and make wonderful additions to the edge of a food forest for inviting in the pollinators and providing a food as well as fiber crop.

Guild Profile:

Great for taking advantage of edge effect, serving as an insectary and for producing not only food but versatile fiber.

You can plant this in full sun near the edge of your food forest.

Harvesting Milkweed For Eating:

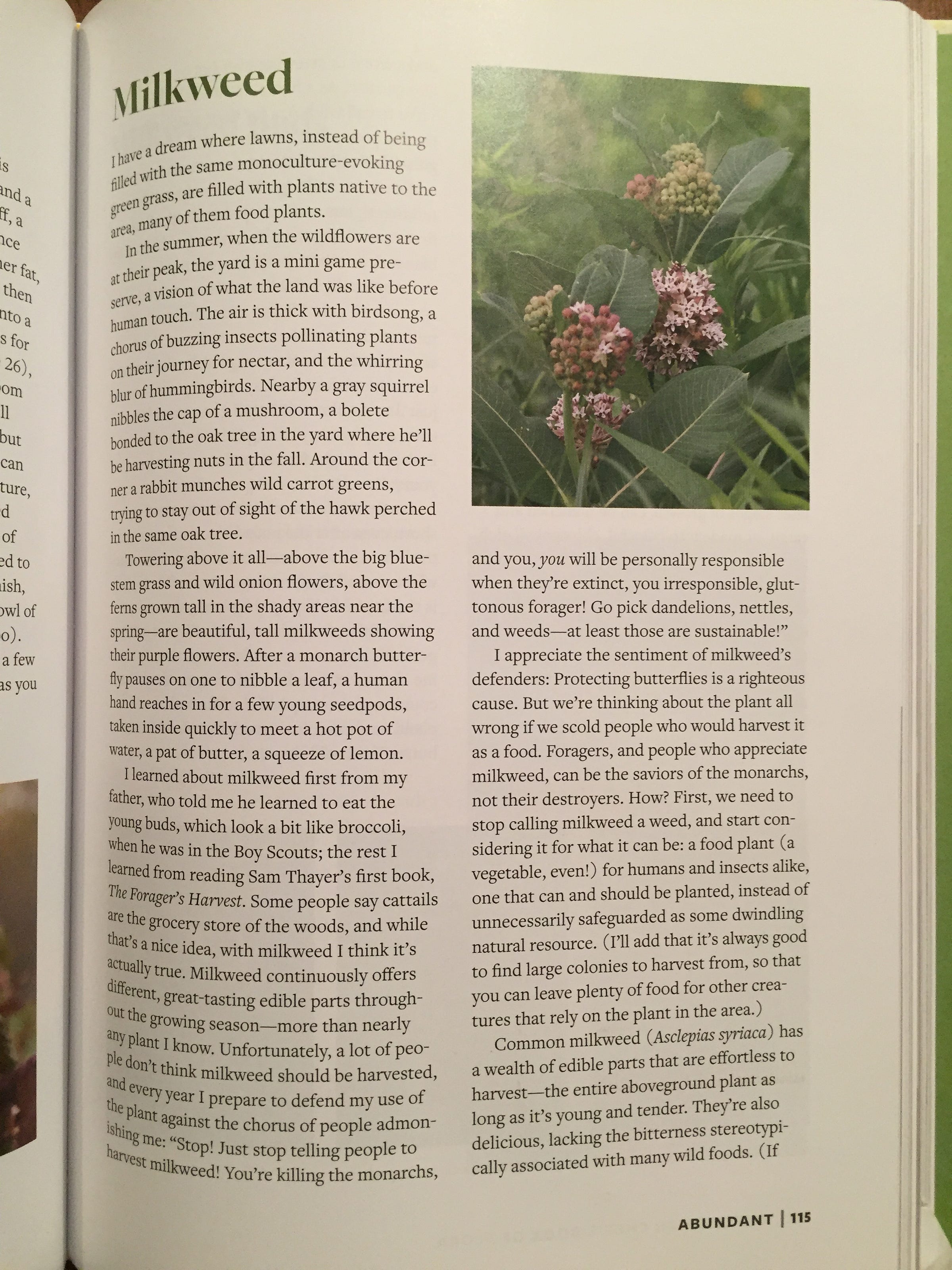

Milkweed is a delicious wild vegetable every food forest designer, regenerative gardener and forager should know, with many different parts that can be uses in everything from savory dishes to desserts.

With all of these uses, it is amazing that milkweed has not become a popular vegetable. The variety of products that it provides ensures a long season of harvest. It is easy to grow (or find) and a small patch can provide a substantial yield. Most importantly, milkweed is delicious. Unlike many foods that were widely eaten by Native Americans, European immigrants did not adopt milkweed into their household economy. We should correct that mistake.

It tastes remarkably like asparagus, only better.

Every time I tell someone this, they immediately say, “Shhh…don’t tell people. We have to save it for the Monarchs!” The truth is, eating milkweed can and will actually help the monarchs.

I’ve seen foragers get a lot of pushback for even talking about eating milkweed. There’s this thought that, if the general public knows that milkweed is not only edible, but delicious, then they’ll eat it all up and there won’t be any for the monarchs.

Reality is just the opposite. Tell people that it’s delicious, and they’re less likely to weed them out of the garden. They’ll tend it carefully, and go out of their way to plant it, knowing that if it’s carefully stewarded you can harvest “wild” milkweed alongside their other vegetables.

Common Milkweed (Asclepias syriaca) is a perennial plant, and with a little care, it can be harvested at all stages of development and it will regrow with increased vigor.

Imagine a plant you can cut in the early stages like asparagus. Then later, when it resprouts, the flower buds can be harvested like broccoli. Then, the flowers themselves are tasty edible flowers.

Leave a few flowers, and after the bees are done with them, the young pods can be cooked like okra. A few weeks later, the immature seeds make a vegan cheese substitute.

Every stage is edible, and milkweed has a new gift to give every week of the summer.

I recently learned though, foraging milkweed in the wild might actually directly help the monarchs. Nomi Foraging discusses this, in relation to his region of Northern Michigan.

“Overwintering sites for these migrating butterflies are in a variety of locations in the southern US and in Mexico. Coupling that fact with their relatively short lifespan of only 2-5 weeks, we know that the Monarch populations that we see in Northern Michigan could be 4-5 generations removed from the original traveler. It is vital for these migrators to arrive here with a hefty supply of food to feed their young. The paradox here is that the most endemic species of Milkweed in our area, and their preferred food source is the Common Milkweed, and by the time these butterflies arrive in Michigan our Common Milkweeds may be too old and tough for most of the Monarch caterpillars to feed on!

This is where we foragers get to help in the cause by feeding ourselves. We benefit, by getting to eat a delicious and healthy vegetable, the Monarchs benefit with fresh and tender leaves to feed their young, and the Milkweed benefits because rhizomatic plants grow more dense with disturbance. Common Milkweed spreads by underground rhizome, which is to say that the portion that you see above ground is not all there is to this story. This underground rhizome spreads rapidly underground creating clonal colonies of milkweed that all originate from the same source. When Common Milkweed is cut back to the ground, it has the amazing ability to resprout from its rhizome. Which works out wonderfully for both the Monarchs, the Milkweed, and us humans.”

Besides the monarchs, milkweed naysayers may claim that it's not edible, that the plant is in fact poisonous to humans. This is not true, it only applies to milkweed in it's raw, uncooked form.

Common milkweed contains a small amount of toxins that are soluble in water. (Before you get too worried, remember that tomatoes, potatoes, ground cherries, almonds, tea, black pepper, hot pepper, mustard, horseradish, cabbage, and many other foods we regularly consume contain small amounts of toxins.) Boiling milkweed parts until tender and then discarding the water, which is the usual preparation, renders them perfectly safe. Milkweed is also safe to eat in modest quantities without draining off the water. Do not eat mature leaves, stems, seeds, or pods.

Raw, milkweed contains cardiac glycosides and other compounds that need to be denatured by cooking. Typically the plant is blanched in boiling, salted water, but I also enjoy the buds steamed and fermented.

-

Finding and Identifying Milkweed:

You might laugh at the proposition of looking for milkweed, as this plant is so well known and widespread that many of us would have trouble hiding from it. Common milkweed occurs across the eastern half of the continent, except for the Deep South and the Far North. It grows well up into Canada and west to the middle of the Great Plains.

Milkweed is a perennial herb of old fields, roadsides, small clearings, streamsides, and fencerows. It is most abundant in farm country, where it sometimes forms large colonies covering an acre or more. The plants can be recognized at highway speeds by their distinct form: large, oblong, rather thick leaves in opposite pairs all along the thick, unbranching stem. This robust herb attains a height of four to seven feet where it is not mowed down. The unique clusters of drooping pink, purple, and white flowers, and the seedpods that look like eggs with one end pointed, are hard to forget.

The young shoots of milkweed look a little like those of dogbane, a common plant that is mildly poisonous. Beginners sometimes confuse the two, but they are not prohibitively difficult to tell apart.

Dogbane shoots are much thinner than those of milkweed, which is quite obvious when the plants are seen side-by-side. Milkweed leaves are much bigger.

Dogbane stems are usually reddish-purple on the upper part, and become thin before the top leaves, while milkweed stems are green and remain thick even up to the last set of leaves. Milkweed stems have minute fuzz, while those of dogbane lack fuzz and are almost shiny.

Dogbane grows much taller than milkweed (often more than a foot) before the leaves fold out and begin to grow, while milkweed leaves usually fold out at about six to eight inches. As the plants mature, dogbane sports many spreading branches, while milkweed does not. Both plants do have milky sap, however, so this cannot be used to identify milkweed while those of dogbane lack fuzz and are almost shiny.

There are several species of milkweed besides the common milkweed. Most are very small or have pointed, narrow leaves and narrow pods. Keep in mind that this article refers specifically to Asclepias syriaca, the common milkweed, although other plants may be locally called “milkweed.” Of course, it goes without saying that you should never eat a plant unless you are absolutely positive of its identification. If in doubt about milkweed in a particular stage, mark the plants and watch them throughout an entire year so that you know them in every phase of growth. Consult a few good field guides to assure yourself. Once you are thoroughly familiar with the plant, recognizing it will require nothing more than a glance.

Common milkweed’s reputation as a bitter pill is almost certainly the result of people misidentifying dogbane or other, bitter milkweeds. Keep in mind this rule of mouth: If the milkweed is bitter, don’t eat it! Accidentally trying the wrong species might leave a bad taste in your mouth, but as long as you spit it out, it will not hurt you. Never eat bitter milkweed.

Milkweed should be a lesson to us all; it is a foe turned friend, a plant of diverse uses, and one of the most handsome herbs in our landscape. We are still discovering and re-discovering the natural wonders of this marvelous continent. What other treasures have been hiding under our noses for generations? (source)

-

Fore more info on identification of milkweed shoots:

https://learnyourland.com/milkweed-and-dogbane-identification-and-sustainable-foraging/

https://the3foragers.blogspot.com/2015/05/milkweed-shoots-vs-dogbane-shoots.html

Wear gloves to avoid the sap

When harvesting any part of the plant, it's easy to get some of the white sap or latex on you. The sap is sticky and can be difficult get off your hands. The sap can make yor fingers sore after long periods of contact. You also need to make sure you don't get it in your eyes, as could happen if you wipe them in the heat of the sun.

Harvesting milkweed can be done sustainably (and even regeneratively) and not at all interfere with the Monarchs. Here's a few things to consider:

Monarchs eat milkweed past the stage of being edible for humans. For example, they will eat pods that have matured and wouldn't be safe to eat, as well as leaves that humans would find old and tough.

If you see a monarch caterpillar on a plant, leave that plant alone-they were there first.

Milkweed regrows after cutting. What that means, is that if you go to the milkweed in the spring or early summer, and cut down, mow, or harvest the shoots of some of the plants, they will continue to grow and produce shoots, buds, tender tops, flowers, and pods, but they will not reach the height of plants that have not been cut.

Only harvest milkweed from healthy colonies. Around farm fields, prairie and wild areas. If you only see a couple plants, leave them be.

If you help spread seeds each place you harvest into more ideal locations you help this plant proliferate for both humans and winged beings to appreciate in the future.

Ethical Harvesting and Nurturing Practices

With the excitement of harvesting from common milkweed, however, comes a serious responsibility. New farming techniques over the last 20 years have eliminated many of the hedges that used to be full of milkweed. Because of this issue, the monarchs have been in serious decline. When I teach this plant during wild plant walks, I tell people who want to eat milkweed that if you want to do so, you have to do your part first. Given the decline of monarchs and milkweed, it is necessary to first propagate it.

Some people harvest milkweed from the wild for eating and due to the reasons I have listed above in this article they feel that they are A: not harming the monarchs chances or B: helping them out due to the harvesting stimulation helping milkweed to grow better. That may be true, but for me, I only harvest large amounts of milkweed for eating from my own plantings so that I can ensure that I always give more than I take and live with a reciprocal, regenerative and reverent relationship with both the plant and the winged beings that depend on her to survive.

This is Dana O'Driscoll’s suggestion for ethical harvesting and tending: find where the milkweed grows in year 1. Observe it, see the monarch larvae enjoying the leaves. In the fall, come to the patch and harvest some of the seed pods (not all). Scatter some seeds just beyond the current patch. Then, scatter them in at least 4 new places that will be good for milkweed. If you have land, save seeds and start them in the spring (put them in the fridge for a few weeks before planting; they need a few weeks of cold stratification). If you don’t know where milkweed is at all, order some seeds online and start a patch. Plant them in your veggie garden or along with your house or in a community garden plot–they are a vegetable!

In year two, once you’ve established a new milkweed patch and have scattered the seeds, it is now ethical to harvest some (but not all) of that patch. Keep spreading the seeds anywhere you can. We need a lot more milkweed out there. So for every plant you harvest from, you should be planting three more! This is what reciprocation is all about–we can eat delicious vegetables from nature, but while we do so, give back more than we are taking.

Every year, I suggest scattering more of the milkweed seeds and getting others to grow them. We can all do our part to help these amazing butterflies and plants continue to thrive. I think doing whatever you can to create more milkweed is necessary before harvesting it. This creates a positive relationship with the plant, shows you are ready to give before you are ready to take, and honors the spirit of both the milkweed and the monarch. (source)

Harvesting different parts of the plant for eating:

Shoots

Milkweed shoots are the first harvest the plant gives, and they're a good vegetable.

You should at least blanch them until they're tender (roughly 1-3 minutes). When I harvest them, similar to asparagus, I cut them where they're tender, typically the top 4-6 inches of the plant.

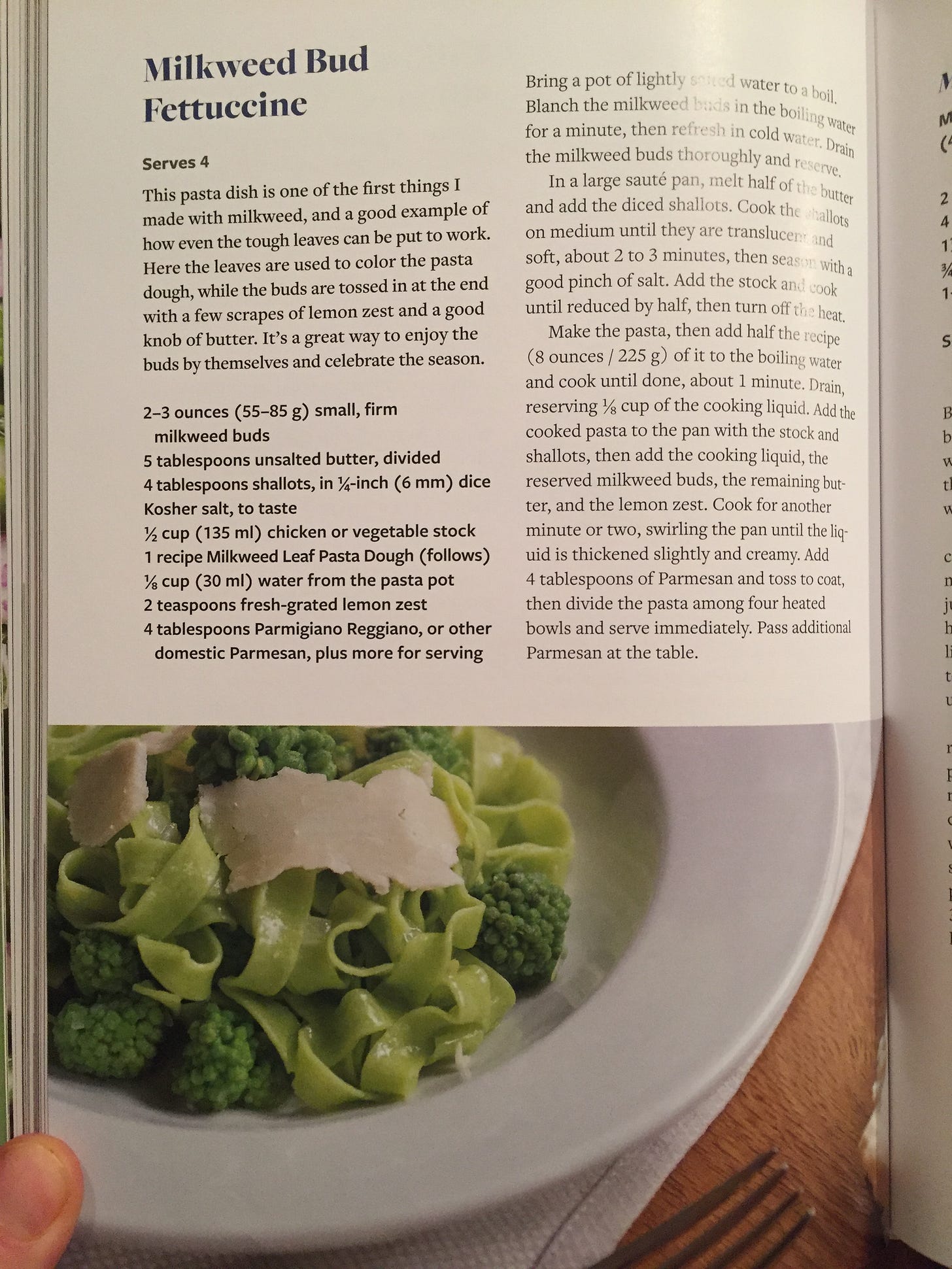

Tops / Clouches

When the young flower buds are just starting, the young growing tops of the plant make a great little vegetable. Just remove the top of the plant, tender leaves, young flower buds and all. Typically I blanch them before adding to a dish.

Unripe Buds / Raabs

Milkweed broccoli. Besides the pods, these are my favorite part of the plant to eat. Harvested at the right stage, when the buds are large and formed, but still tightly bunched around the stems, these make a great vegetable, and can be harvested in large quantities in a large patch.

Great blanched but even better steamed.

A mix of butter and a sauce of fermented ramp leaves is one of the best things I've ever eaten on them. There's all kinds of recipes out there for milkweed buds, and you can probably use them just about any way you would broccoli. Use your imagination.

Preservation of buds

Since you can harvest far more milkweed buds than I can eat, coming up with a few different ways to preserve them is recommended.

Dehydration

The buds can easily be dehydrated and stored in a jar or other container until you're ready to use them. To refresh them for eating, simply simmer them in some water to cover until they're tender and taste good to you. To dry the buds, put them on a drying rack and dehydrate at 90-100F until cracker dry, then store in an air-tight container.

Blanching and freezing

Milkweed buds, as well as the shoots and leaves, can also be blanched and frozen for storage.

Flowers

The flowers of milkweed are a really special thing. The plant produces multiple clusters of strongly floral, aromatic flowers, sometimes growing as large as a softball on some plants I've seen. The really fascinating thing about the flowers is their flavor.

Milkweed flowers, like most other parts of the plant, can be harvested in large quantities, and, as such, it should come as no surprise that indigenous peoples of North America harvested them specifically as a food. The flowers, like the buds, can be dried and rehydrated such as in adding to a brothy soup, where they can be nice.

Using with liquids

When milkweed flowers are put into liquid (see Alan Bergo’s milkweed flower shrub for an example), after a few days, they will start to "bleed", turning the liquid a bright, vibrant reddish-pink, as well as transferring their perfume to the liquid. A sugar syrup made with a shrub has a tendency to make drinks taste a bit like Watermelon Jolly Ranchers to me-they have a curiously strong, fruity quality to them.

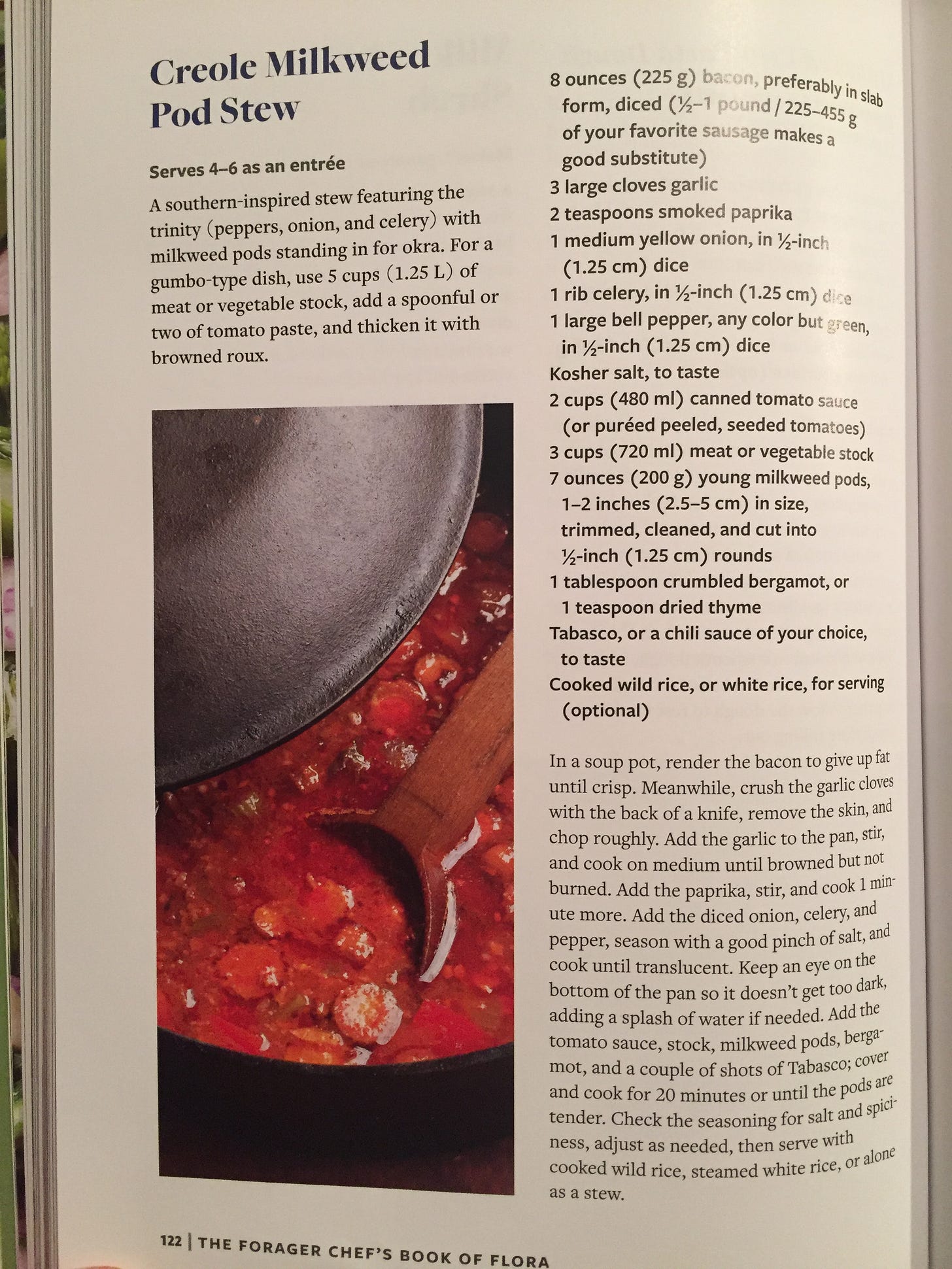

Pods

There's lots of wild leafy greens out there, but there are not many truly wild vegetables, so the pods of milkweed are, by far, my favorite part of the plant. Unlike okra, milkweed doesn't have a mucilagenous/slimy quality to it, so people that don't like okra may find themselves enjoying milkweed.

Harvest pods 2 inches long or less

Just like every other part of the plant, the pods of milkweed have a specific stage of growth where they're good to eat. This stage, as mentioned by Sam Thayer, is just about 2 inches in length. smaller than two inches, and they're a bit too small and undeveloped for me. Longer than two inches, and the outer green covering of the pod will become tough.

Milkweed pods must be cooked to be safe, just like the shoots, tender tops and flower buds. Many people blanch their milkweed pods, and I recommend doing that if it's your first time, but I occasionally make fried milkweed pods from the fresh pod by just soaking them in buttermilk, tossing in cornmeal, and frying as-is.

Just like with other portions of the plant, overconsumption is not advised if you're new to eating it, and some people may need to have milkweed pods blanched before cooking.

Silk

The last gift that milkweed gives is the immature, tender silk on the inside of the pod. With a tender, albeit interesting texture and mild milkweed flavor, the silk can be an interesting thing to try if you find your pods are all past the 2 inch mark, but are not yet starting to produce mature seeds on the inside. The silk should only be harvested when young, tender, and pure white.

If your milkweed pods have visible seeds on the inside, they're too old, and should not be eaten. The silk can be cooked without blanching by tossing into a pan along with other vegetables, preferably in a wet environment like a stew or juicy casserole. Like all other edible parts of the plant, it must be cooked.

Harvesting Milkweed For Fiber (using the “floss” or seed fluff as a cruelty free option for insulation for clothing/pillows):

Numerous uses for Milkweed Floss have been explored throughout history due to its unique properties. Milkweed Floss is a sustainable (and potentially regenerative) fiber that is:

Six times warmer than wool.

Hypoallergenic.

More buoyant than cork.

It is a “cruelty-free” alternative to goose down and has the same light-weight, soft, qualities for use as a batting fiber in comforters, pillows, and jackets. The floss that carry the seeds in the wind are very similar in structure to goose down. Numerous fibers radiate from a central core. Goose down tends to be denser by volume, but Milkweed plumes are composed of longer filaments and springs back after being crushed with much of the same resilience (or “loft”) as goose down.

In the 1800s, uses for milkweed floss included mattress filling while other parts of the plant went into making netting and socks. Newspaper accounts from the 1940s excitedly described milkweed as a future commercial success, useful for clothing, insulation, paints, plastics, and wax.

Making yarn from Milkweed Floss is an amazingly rewarding experience – albeit one that requires some skill and finesse.

Spinning Milkweed Floss – most commonly, combined with wool – creates a yarn that feels like angora and spins easily. It is soft and has a slight sheen to it in the places where the Milkweed Floss has woven with the yarn, much like hints of spun silk.

It is recommended to use a blend when making yarn from Milkweed Floss. As Spinoff Magazine writes about making yarn from Milkweed:

Milkweed seedpod fiber, or floss, tends to create a brittle yarn when spun alone. But blending the floss with another fiber such as wool or cotton will add structural strength to the shimmering milkweed fiber. The ratio of wool to milkweed blend is a personal preference, although it is important to keep a higher percentage of wool for the sake of strength and structure. The process of blending milkweed floss with wool is similar to creating any carded wool rolag or batt, such as those combined with silk or mohair. As with any specialty fiber, if the milkweed is overcarded, it can break and tangle.

Build Your Own Milkweed Seed and Floss Separator

https://monarchwatch.org/bring-back-the-monarchs/docs/milkweed-manual-old2.pdf

Make a Jacket With Milkweed Seed Floss

https://www.motherearthnews.com/diy/make-a-jacket-milkweed-seed-zmaz79sozraw/

Processing, spinning and knitting milkweed fiber

https://inconsequentialblogger.blogspot.com/2014/04/processing-spinning-and-knitting.html

Traditional Medicinal/Material Uses:

Asclepias syriaca was used widely for a variety of purposes. As a food, people ate the boiled young sprouts like asparagus, cooked the unopened floral bud clusters and firm green fruits, as well as the tender leaves and upper stalks. The flowers and buds often thickened soups. Dried buds were stored for winter use. The latex was boiled and mixed with animal fat for a chewing gum. As a craft product, the fibers were used as cordage for bowstrings and fine sewing threads. Fibers from inside the large pods were used as a stuffing for pillows and sleeping pads for babies. The milky juice was used as a glue. As a medicine, the plant supported treatment of venereal diseases, kidney and urinary dysfunction, rheumatism, and backaches. It was also used as a laxative, galactagogue, and contraceptive. Topically it was used to remove warts and treat bee stings, cuts, and ringworm.

Practical Modern Uses in the Regenerative Garden and on the edge of the Food Forest:

For modern purposes, milkweed has the following uses and benefits:

Improves Biodiversity

Because the relationship between caterpillars, butterflies, monarch migration and milkweed is such a complex issue, it sometimes feels like it’s out of our control. Nothing could be further from the truth!

Milkweed works to build stronger biodiversity in your neighborhood and beyond, and it has several other benefits, too.

Provides Pest Control, Including Stink Bugs

Milkweed actually has the power to make your life easier in the garden. A Washington State University study investigating the pest-control aspects of the plant turned up some really interesting findings:

It is a cheap and simple way to support pollinator health and to get pests under control.

Native milkweed plants attract beneficial insects like parasitic wasps, carnivorous flies and predatory bugs that suppress common pests like aphids, leafhoppers, thrips and even stink bugs

Another recent study highlighted a Georgia peanut farm that successfully used milkweed plantings to increase Tachinid fly numbers. Why would you want these insects? They act as parasites to pesky Japanese beetles and stink bugs, offering inexpensive, chemical-free pest control.

Helps Clean Contaminants

The “silk” found in milkweed pods is often utilized to help absorb contaminants during oil spills.

Interestingly, the seed pod fibers absorb more than four times the amount of oil compared to the plastic-based materials currently used during oil spill cleanup projects. Encore3, a Canadian company, created milkweed fiber-based kits that absorb 53 gallons of oil at a rate of .06 gallons per minute.

How does that cleanup rate compare to the polypropylene products on the market? It sponges up spilled oil twice as fast.

Milkweed Down: Nature’s Powerhouse Fiber

1. Insulation in Outdoor Clothing

The insulating properties of milkweed down make it perfect for use in outdoor clothing. With its lightweight, thermal characteristics, it can keep you warm in even the most frigid conditions. This feature makes it an excellent filling for jackets, gloves, hats, and sleeping bags.

2. Home Insulation

Did you know that milkweed floss can also insulate your home? It’s an eco-friendly alternative to synthetic insulation. Its thermal properties keep homes warm in winter and cool in summer, resulting in energy savings and a reduced carbon footprint.

3. Life Jackets

Milkweed down’s buoyancy was recognized during World War II when it was used as stuffing for life jackets. Today, it can still be utilized in floatation devices due to its water-resistant and lightweight properties.

4. Oil Spill Cleanup

Milkweed floss has impressive oil absorption capabilities, making it a powerful tool for cleaning up oil spills. It can effectively absorb oil while repelling water, making cleanup easier and more environmentally friendly.

5. Hypoallergenic Pillows and Bedding

For those who suffer from allergies to traditional down, milkweed down is an excellent alternative. It’s hypoallergenic, breathable, and provides a comfortable and warm sleeping environment.

6. Natural Fire Starters

The fluff from milkweed down can be used as a natural fire starter. It catches flame easily and can help you start a fire when camping or during survival situations.

7. Composting Material

Being a natural material, milkweed down is fully biodegradable and can be added to compost piles. It helps add volume and fiber to the compost, thereby enhancing the decomposition process.

8. Craft Projects

Milkweed down can be used in various craft projects. It’s soft, fluffy, and easy to work with. It can be used for stuffing toys or making natural decorations.

9. Pet Bedding

The softness and warmth of milkweed floss make it an ideal filling for pet beds. It creates a cozy, comfortable space for your furry friends while being safe and non-toxic.

10. Sustainable Packaging Material

With its lightweight and padding properties, milkweed down could be used as a sustainable alternative to traditional packaging materials. It can protect fragile items during transportation, all while being eco-friendly.

By utilizing milkweed down, we are not only taking advantage of its versatile uses but also contributing to the welfare of the environment and promoting biodiversity. Cultivating milkweed supports the survival of the Monarch butterfly, a species critically dependent on milkweed plants for their lifecycle.

Fibers for making twine

A good quality fibre is obtained from the inner bark of the stems. It is long and quite strong, but brittle. It can be used in making twine, cloth, paper etc. It is easily harvested in late autumn after the plant has died down by simply pulling the fibres off the dried stems. It is estimated that yields of 1,356 kilos per hectare could be obtained from wild plants.

Other uses:

Candlewicks can be made from the seed floss.

Rubber can be made from latex contained in the leaves and the stems. It is found mainly in the leaves and is destroyed by frost.

The latex can also be used as a glue for fixing precious stones into necklaces, earrings etc. The latex contains 0.1 - 1.5% caoutchouc, 16 - 17% dry matter, and 1.23% ash.

Pods contain an oil and a wax which are of potential importance. The seed contains up to 20% of an edible semi-drying oil.

It is also used in making liquid soap

Could be integrated into various agroforestry systems rather than as monocultures

Children’s lab: Young children have so many things to learn and marvel in milkweed patches. They can learn how:

Ants farm aphids for their honeydew

Wasps stop on the plants to eat the aphids’ honeydew

Red and black milkweed bugs live and mate (quite often) on milkweed plants

Predatory insects find aphid infested milkweed patches and lay their eggs on the plants. Lacewing and ladybug eggs hatch into ravenous, carnivorous larvae.

Insect morphology works. Watch as monarch eggs hatch to larvae that become huge then form chrysalises where they turn into nothing but goo and completely reform into butterflies.

Utensils: Some Native Americans used mature, dried milkweed pod halves as spoons.

Seed Propagation:

Fall is the perfect time to collect seeds and start sowing.

Fall is the time for direct sowing seeds outdoors. The benefit is that nature provides the winter conditions needed to stratify the seeds. This is how “empress of dirt” sows native seeds including milkweed outdoors during the cold seasons.

stratification is a process where the cold and damp of winter naturally prepares the seeds for spring germination. See How To Stratify Seeds for more information.

Another option is to sow the seeds indoors. It’s a long, slow process, just as it is outdoors, but can be done. There are milkweed enthusiasts who have their routine down to a science and get good germination rates. Ultimately, they are ensuring that the seeds have exposure to cold and damp over a sufficient period of time to ensure their seeds sprout and then provide optimum seed starting conditions. If this is something that interests you, it’s a fun pursuit.

You may also want to try winter sowing in containers.

No matter how you do it, it will take several months including the cold stratification period to eventually grow.

As soon as the seedlings are large enough to handle, gently pull them out into individual pots. Plant out when they are in active growth in late spring or early summer and give them some protection from slugs until they are growing away strongly. Division in spring. With great care since the plant resents root disturbance.

For more info on cultivating Milkweed from seed, read:

Cultivation details:

Succeeds in any good soil but will grow just fine in poor soil as well. Prefers a well-drained light rich or peaty soil (though also grows in compacted clay abused agricultural soils too). Requires a sunny position. Plants are hardy to about -25°c. Plants resent root disturbance and are best planted into their final positions whilst small. The plant is heat tolerant in zones 9 through 2.

Milkweed In The Kitchen

How to Cook Milkweed

Ok, so milkweed is edible. Now what? How on earth do you cook it?

That really depends a lot on when you find milkweed in the wild, or harvest it from your milkweed veggie patch. The first edible stage is the young shoots and leaves.

Milkweed flower buds first appear in early summer and can be harvested for about seven weeks. They look like miniature heads of broccoli but have roughly the same flavor as the shoots. These flower buds are wonderful in stir-fry, soup, rice, casseroles, and many other dishes. Just make sure to wash the bugs out.

In late summer milkweed plants produce the familiar pointed, okra-like seedpods which are popular in dried flower arrangements. These range from three to five inches long when mature – but for eating you want the immature pods. Select those that are no more than two thirds of their full size. It takes a little experience to learn the knack of how to tell if the pods are still immature, so as a beginner you might want to stick to using pods less than 1 3⁄4 inches in length to be safe. If the pods are immature the silk and seeds inside will be soft and white without any hint of browning. It is good to occasionally use this test to verify that you are only choosing immature pods. If the pods are mature they will be tough and bitter. Milkweed pods are delicious in stew or just served as a boiled vegetable, perhaps with cheese or mixed with other veggies.

Silk refers to the immature milkweed floss, before it has become fibrous and cottony. This is perhaps the most unique food product that comes from the milkweed plant. When you consume the pod, you are eating the silk with it. You can eat the smallest pods whole, but we like to pull the silk out of the larger (but still immature) pods. Open up the pod along the faint line that runs down the side, and the silk wad will pop out easily. If you pinch the silk hard, your thumbnail should go right through it, and you should be able to pull the wad of silk in half. The silk should be juicy; any toughness or dryness is an indicator that the pod is overmature. With time, you will be able to tell at a glance which pods are mature and which are not.

Milkweed silk is both delicious and amazing. It is slightly sweet with no overpowering flavor of any kind. Boil a large handful of these silk wads with a pot of rice or cous cous and the finished product will look like it contains melted mozzarella. The silk holds everything together, so it’s great in casseroles as well. It looks and acts so much like cheese, and tastes similar enough too, that people assume that it is cheese until I tell them otherwise. I have not yet run out of new ways to use milkweed silk in the kitchen – but I keep running out of the silk that I can for the winter! (source)

Recipes:

More specific recipe ideas:

5 Ways to Prepare Milkweed Flowers ~ Farm and Forage Kitchen

Cream of Milkweed Soup ~ 3 Foragers

Milkweed Flower Cocktail ~ Backyard Forager

Milkweed and Radish Salad ~ Our One Acre Farm

Milkweed Mushroom Moo Shu ~ Very Vegan Val

Traditional Potawatomi Nation Preparations (Native American Milkweed Recipes)

Videos about growing, foraging for and cooking milkweed:

References:

https://www.sciencedirect.com/topics/agricultural-and-biological-sciences/asclepias-syriaca#:~:text=The%20healing%20properties%20of%20the,and%20have%20high%20biological%20activity.

https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/abs/pii/S0926669008001179

https://thenaturopathicherbalist.com/2015/09/06/asclepius-tuberosa/

https://cals.cornell.edu/weed-science/weed-profiles/common-milkweed

https://www.outdoorapothecary.com/milkweed/

https://milkweedfloss.com/10-amazing-uses-for-milkweed-down/

https://www.foragersharvest.com/newsletter/milkweed-a-truely-remarkable-wild-vegetable

https://empressofdirt.net/growing-milkweed-seed/

https://foragerchef.com/guide-to-milkweed/

https://thedruidsgarden.com/2018/06/30/wild-food-profile-milkweed-fried-milkweed-pod-recipe/

https://practicalselfreliance.com/milkweed/

https://backyardforager.com/milkweed-asclepias-syriaca/

https://foragerchef.com/milkweed-shoots/

https://www.outdoorapothecary.com/milkweed/

https://projectfoodforest.org/2016/08/16/common-milkweed-asclepias-syriaca/#:~:text=But%20did%20you%20know%20that,as%20we%20have%20ethnobotanical%20evidence.

https://www.natureinstitute.org/article/craig-holdrege/the-story-of-an-organism-common-milkweed

https://milkweedfloss.com/uses-for-milkweed-floss/

https://happyeconews.com/milkweed-clothing-insulation/

Anderson, W. P. 1999. Perennial Weeds: Characteristics and Identification of Selected Herbaceous Species. Iowa State University Press, Ames.

Baskin, J. M., and C. C. Baskin. 1977. Germination of milkweed (Asclepias syriaca L.) seeds. Bulletin of the Torrey Botanical Club 104:167-170.

Bhowmik, P. C. 1978. Germination, growth and development of common milkweed. Canadian Journal of Plant Science 58:493-498.

Bhowmik, P. D. 1994. Biology and control of common milkweed (Asclepias syriaca). Reviews of Weed Science 6:227-250.

Bhowmik, P. C., and J. D. Bandeen. 1976. The biology of Canadian weeds. 19. Asclepias syriaca L. Canadian Journal of Plant Science 56: 579-589.

Burrows, G. E., and D. J. Tyrl. 2006. Handbook of Toxic Plants of North America. Blackwell: Ames, IA.

Cramer, G. L., and O. C. Burnside. 1982. Distribution and interference of common milkweed (Asclepias syriaca) in Nebraska. Weed Science 30:385-388.

Dhillion, S. S., and C. F. Friese. 1994. The occurrence of mycorrhizas in prairies: Applications to ecological restoration. Thirteenth North American Prairie Conference 13:103-114.

DiTommaso, A., K. M. Averill, M. P. Hoffman, J. R. Fuchsberg, and J. E. Losey. 2016. Integrating insect, resistance, and floral resource management in weed control decision-making. Weed Science 64:743-756.

Doll, J. 2002. Knowing when to look for what: Weed emergence and flowering sequences in Wisconsin. http://128.104.239.6/uw_weeds/extension/articles/weedemerge.htm

Evetts, L. L., and O. C. Burnside. 1972. Germination and seedling development of common milkweed and other species. Weed Science 20:371-378.

Evetts, L. L., and O. C. Burnside. 1973. Common milkweed seed maturation. Weed Science 21:568-569.

Evetts, L. L., and O. C. Burnside. 1974. Root distribution and vegetative propagation of Asclepias syriaca L. Weed Research 14:283-288.

Evetts, L. L., and O. C. Burnside. 1975. Effect of competition on growth of common milkweed. Weed Science 23:1-3.

Farmer, J. M., S. C. Price, and C. R. Bell. 1986. Population, temperature, and substrate influences on common milkweed (Asclepias syriaca) seed germination. Weed Science 34:523-528.

Gaertner, E. E. 1979. The history and use of milkweed (Asclepias syriaca L.). Economic Botany 33:119-123.

Hochwender, C. G., R. J. Marquis, and K. A. Stowe. 2000. The potential for and constraints on the evolution of compensatory ability in Asclepias syriaca. Oecologiea 122:361-370.

ISC. Invasive Species Compendium. Asclepias syriaca (common milkweed). http://www.cabi.org/isc/datasheet/7249

Jeffery, L. S., and L. R. Robinson. 1971. Growth characteristics of common milkweed. Weed Science 19:193-196.

Kevan, P. G., D. Eisikowitch, and B. Rathwell. 1989. The role of nectar in the germination of pollen in Asclepias syriaca L. Botanical Gazette 150:266-270.

Morse, D. H., and R. S. Fritz. 1983. Contributions of diurnal and nocturnal insects to the pollination of common milkweed (Asclepias syriaca L.) in a pollen-limited system. Oecologia 60:190-197.

Morse, D. H., and J Schmitt. 1985. Propagule size, dispersal ability, and seedling performance in Asclepias syriaca. Oecologia 67:372-379.

Pleasants, J. M. 1991. Evidence for short-distance dispersal of pollinia in Asclepias syriaca L. Functional Ecology 5:75-82.

Robbins, W. W., A. S. Crafts, and R. N. Raynor. 1942. Weed Control: a Textbook and Manual. McGraw-Hill: New York.

Sauer, D., and D. Feir. 1974. Population and maturation characteristics of the common milkweed. Weed Science 22:293-297.

Seiber, J. N., L. P. Brower, S. M. Lee, M. M. McChesney, H. T. A. Cheung, C. J. Nelson, and T. R. Watson. 1986. Cardenolide connection between overwintering monarch butterflies from Mexico and their larval food plant, Asclepias syriaca. Journal of Chemical Ecology 12:1157-1170.

Sosnoskie, L. M., E. C. Luschei, and M. A. Fanning. 2007. Field margin weed-species diversity in relation to landscape attributes and adjacent land use. Weed Science 55:129-136.

Stamm-Katovich, E. J., D. L. Wyse, and D. D. Biesboer. 1988. Development of common milkweed (Asclepias syriaca) root buds following emergence from lateral roots. Weed Science 36:758-763.

Stevens, O. A. 1924. Effects of the first fall freeze. The American Midland Naturalist 9:14-17.

Stevens, O. A. 1932. The number and weight of seeds produced by weeds. American Journal of Botany 19:784-794.

Vannette, R. L., and M. D. Hunter. 2011. Plant defence theory re-examined: non-linear expectations based on the costs and benefits of resource mutualisms. Journal of Ecology 99:66-76.

Willson, M. F., and P. W. Price. 1980. Resource limitation of fruit and seed production in some Asclepias species. Canadian Journal of Botany 58:2229-2233.

Willson, M. F., and B. J. Rathcke. 1974. Adaptive design of the floral display in Asclepias syriaca L. American Midland Naturalist 92:47-57.

Yenish, J. P, T. A. Fry, B. R. Durgan, and D. L. Wyse. 1996. Tillage effects on seed distribution and common milkweed (Asclepias syriaca) establishment. Weed Science 44:815-820.

Yenish, J. P, T. A. Fry, B. R. Durgan, and D. L. Wyse. 1997. Establishment of common milkweed (Asclepias syriaca) in corn, soybean, and wheat. Weed Science 45:44-53.

Agrawal, A. A. (2005). Natural selection on common milkweed (Asclepias syriaca) by a community of specialized insect herbivores. Evolutionary Ecology Research, 7, 651-667.

Barber, J. R., & Conner, W. E. Acoustic mimicry in a predator-prey interaction. PNAS, 104, 9331–9334.

Baum, H. (948). Der Fruchtansatz von Asclepias syriaca. Plant Systematics and Evolution, 94: 402–403.

Berenbaum, M. (1993). Sequestered plant toxins and insect palatibility. The Food Insects Newsletter, 6(3), 1-10.

Bookman, S. S. (1981). The floral morphology of Asclepias speciosa (Asclepiadaceae) in relation to pollination and a clarification of terminology for the genus. American Journal of Botany, 68, 675–679.

Cohen, J. A., & Brower, L. P. (1983). Cardenolide sequestration by the dogbane tiger moth (Cycnia tenera; Arctiidae). Journal of Chemical Ecology, 9,521–532.

Dailey, P. J. Graves, R. C., & Herring, J. L. (1978). Survey of hemiptera collected on common milkweed, Asclepias syriaca, at one site in Ohio. Entomological News, 89, 157–162.

Dailey, P. J. Graves, R. C., & Kingsolver, J. M. (1978). Survey of coleoptera collected on the common milkweed, Asclepias syriaca, at one site in Ohio. The Coleopterists Bulletin, 32, 223–229.

Duffey, S. S., & Scudder, G. G. E. (1972). Cardiac glycosides in North American Asclepiadaceae, a basis for unpalatability in brightly coloured hemiptera and coleoptera. Journal of Insect Physiology, 18, 63–78.

Duffey, S. S., Blum, M. S., Isman, M. B., & Scudder, G. G. E. (1978). Cardiac glycosides: a physical system for their sequestration by the milkweed bug. Journal of Insect Physiology, 24, 639–645.

Dussourd, D. E. (1999). Behavioral sabotage or plant defense: do vein cuts and trenches reduce insect exposure to exudate? Journal of Insect Behavior, 12, 501–515.

Farrell, B. D., & Mitter, C. (1998). The timing of insect/plant diversification: might Tetraopes (Coleoptera: Cerambycidae) and Ascelpias (Asclepiadaceae) have co-evolved? Biological Journal of the Linnean Society 63, 553–577.

Fordyce, J. A., & Malcolm, S. B. (2000). Specialist weevil, Rhyssomatus liineaticollis, does not spatially avoid cardenolide defenses of common milkweed by ovipositing into pith tissue. Journal of Chemical Ecology, 26, 2857–2874.

Fox, C. W., & Caldwell, R. L. (1994). Host-associated fitness trade-offs do not limit the evolution of diet breadth in the small milkweed bug Lygaeus kalmii (Hmiptera: Lygaeidae). Oecologia, 97, 382–389.

Fritz, R. S., & Morse, D. H. (1981). Nectar parasitism of Asclepias syriaca by ants: effect on nectar levels, pollinea insertion, pollinaria removal and pod production. Oecologia, 50, 316–319.

Goethe, J. W. (1995). Scientfic studies. Princeton: Princeton University Press.

Hartman, F. A. (1977). The ecology and coevolution of common milkweed (Asclepias syriaca, Asclepiadacieae) and milkweed beetles (Tetraopes tetraophthalmus, Cerambycidae). Ph.D. Thesis, University of Michigan, Ann Arbor.

Helmus, M. R., & Dussourd, D. E. (2005). Glues or poisons: which triggers vein cutting by monarch catepillars? Chemoecology, 15, 45–49.

Holdrege, C. (2000). Where do organisms end? In Context, 3, 14–16.

Jennersten, O., & Morse, D. H. (1991). The quality of pollination by diurnal and nocturnal insects visiting common milkweed, Asclepias syriaca. American Midland Naturalist, 125, 18–28.

Leopold, A. (1989). A Sand County Almanac. New York: Oxford University Press. This book was originally published in 1949.

Leopold, A. (1999). For the Health of the Land. Washington, D. C.: Island Press. The quotes are from the essay “The Farmer as Conservationist,” which was originally published in 1939.

Kephart, S. R. (1987). Phenological variation in flowering and fruiting of Asclepias. American Midland Naturalist, 118, 64–76.

Malcolm, S. B. (1994/1995). Milkweeds, monarch butterflies and the ecological significance of cardenolides. Chemoecology, 5/6, 3/4, 101–117.

Mooney, K. A., Jones, P., & Agrawal, A. A. (2008). Coexisting congeners: demography, competition, and interactions with cardenolides for two milkweed-feeding aphids. Oikos, 117, 450–458.

Morse, D. H. (1982). The turnover of milkweed pollinia on bumble bees, and implications for outcrossing. Oecologia, 53, 187–196.

Pleasants, J. M. (1991). Evidence for short-distance dispersal of pollinia in Asclepias syriaca L. Functional Ecology, 5, 75–82.

Price, P. W.,& Wilson, M. F. (1979). Abundance of herbivores on six milkweed species in Illinois. American Midland Naturalist, 101, 76–86.

Prysby, M. D. (2004). In Oberhauser, K. S., & Solensky, M. J. (Eds.), The Monarch Butterfly: Biology and Conservation (pp. 79–83). Ithaca: Cornell University Press.

Sage, T. L., & Williams, E. G. 1995). Structure, ultrastructure, and histochemistry of the pollen tube pathway in the milkweed Asclepias syriaca L. Sex Plant Reprod, 8, 257–265.

Solensky, M. J. (2004). Overview of monarch migration. In Oberhauser, K. S., &

Solensky, M. J. (Eds.), The Monarch Butterfly: Biology and Conservation (pp. 79–83). Ithaca: Cornell University Press.

Southwick, E. E. (1983). Nectar biology and nectar feeders of common milkweed, Asclepias syriaca L. Bulletin of the Torrey Botanical Club, 110, 324–334.

Wilbur, H. M. (1976). Life history evolution in seven milkweeds of the genus Asclepias. The Journal of Ecology, 64, 223–240.

Willson, M. F., & Rathcke, B. J. (1974). Adaptive design of the floral display in Asclepias syriaca L. American Midland Naturalist, 92, 47–57.

Woodson, R. E. (1954). The North American species of Asclepias L. Annals of the Missouri Botanical Garden, 41, 1–211.

Wyatt, R. & Broyles, S. B. (1994). Ecology and evolution of reproduction in milkweeds. Annual Review of Ecology and Systematics, 25, 423–441.

Wyatt, R., Browles, S. B. & Derda, G. S. (1992). Environmental influences on nectar production in milkweeds (Asclepias syriaca and A. exaltata). American Journal of Botany, 79, 636–642.

The above post was the 15th installment of a series titled Stacking Functions in the Garden, Food Forest and Medicine Cabinet : The Regenerative Way From Seed To Apothecary.

I hope this inspires you to try growing some of your own at home and spreading those seeds in the wild where you live. Plants like this can become long term allies and teachers to us humans if we just choose to use these human hands of ours to co-create, tend and plant seeds and use our eyes, hearts and minds to learn, adapt and expand our understanding.

The genius, elegance and grace that is embodied in each living seed that I collect, sow and tend never ceases to amaze me and enrich my mind. Every moment spent in the presence of our photosynthetic elders offers an opportunity to learn something new if we open our heart and our eyes to be receptive with humility.

If you look really closely, observing how the seeds of the wild and the seeds in your garden express themselves in form, how they forge alliances with other beings, aligning with the elemental abundance of the Earth and harnessing the forces of nature to achieve their sacred goals, you will know everything you need to know to live a life of peace, health, fulfillment, joy, purpose, abundance and grace.

Thank you so much Gavin for sharing this precious information and also for your beautiful writing!

awesome article. I knew milkweed was great for pollinators and insulation but had no idea it was edible.

as usual, your well-annotated presentation of data is appreciated.