Mole Polbano Dry Spice Mix and Sauce

This post shares another recipe from my book and some info on the highly productive food cultivation system that was utilized by the Triple Alliance (aka 'Aztec') people called Chinampas

An ancient dish, Mulli, the Nahuatl (aka ‘Aztec’) word for mole means mix or sauce. It is an exquisite delicacy from the colonial city of Puebla, México. It has been called the national dish of Mexico. Mole had its origin in pre-hispanic Mexico, when it was called mulli and was made with turkey and served in Triple Alliance (aka ‘Aztec’) rituals and other festive occasions.

Fray Bernardino de Sahagún described the dish for the first time in his book "Historia General de las Cosas de la Nueva España" (General History of the Things of the New Spain). He described a ceremonial stew that was specially prepared for Moctezuma and as an offering to the gods. The stew, prepared with chiles, pumpkin seeds, cacao, hierba santa, and tomato, was called "Mulli." This translates into sauce or paste in the Nahuatl tongue, and the word has evolved into what we know today as "mole."

One of the most treasured ingredients used in the mole is xocolatl – the Nahuatl word for chocolate (or rather a mixture of raw cacao beans and other ingredients). The Nahuatl speaking people of the Triple Alliance (commonly referred to as “Aztec” people) did not only inspire some of the delicious foods we eat today, they also offer us wisdom in how we might develop regenerative food cultivation systems in lagoons, swamps and lakes through their floating garden cultivation systems called “Chinampas” (more on this at the end of this post) but first, what is Mole Sauce?

With the arrival of the Spaniards, they brought new ingredients like anise, black pepper, and cinnamon to Mexico. In Pre-hispanic times, mole was served with turkey, duck, or armadillo. After the Spaniards arrived, chicken or pork was used. During Mexican colonial times, there were many ingredients from the new and old worlds to cook with, and from the fusion of these two cultures, mole, as we know and love it today, has evolved.

Our recipe combines the flavors of pre-colonial Mesoamerica with the spices that were brought over from Europe and Asia.

Today we have many different moles unique to every region of Mexico, each one of them utilizing local ingredients. From the Pre-hispanic times until today, mole represents a celebration of Mexican culture and is the main dish in every party, wedding, or quinceañera. Mole is every Mexican's favorite dish and is a symbol of our cultures, traditions, and ancestral heritage.

One of the legends of the origins of Mole talk about the Santa Rosa convent in Puebla, where the nuns created this exquisite dish by improvising with an unlikely list of ingredients back in 1680 to please Viceroy Tomás Antonio de la Cerda y Aragón. One thing is certain, and that is that the current Mole Poblano is from the region of Puebla and it is different from the Mole Negro from Oaxaca. Today, there are more than 300 different moles, as the combinations of ingredients could be endless.

Of the many different ingredients found in the dish, the main ones are chili peppers, chocolate, plantains, almonds, pumpkin seeds, cinnamon sticks, anise, and cloves. These eight ingredients are among the most interesting ingredients found in Mole Poblano, not only because they are essential to the dish, but because they have long complex histories that date back to the ancient, pre-Columbian empires of Mesoamerica.

If one was to trace the origins of the ingredients that came with the Spaniards to what is now called Mexico it could also be said that the origins of mole poblano may be in part found in the sophisticated thousand-year-old Persian cuisine which was adopted by Muslims in Baghdad and subsequently spread to other Muslim cities, flourishing from the eighth century onward. A southern portion of the Iberian Peninsula, termed al-Andalus, also came under Muslim control in the eighth century, resulting in the spread of many non-native foods and crops to the region. Over hundreds of years, popular dishes from al-Andalus were adopted by nearby Christian Europe, sometimes substituting one ingredient for another within recipes. As Spain gained territory in America during the 16th century, their cuisine traveled with them, including that which had originally been adopted from the Muslims. Among these ingredients was what would become foundational ingredients for the creation of mole poblano, created via the combination of some Spanish ingredients with ones native to America.

While mole may be eaten on ordinary days for any meal, many Mexicans serve it during holidays and special occasions, like Día de Muertos and weddings. In Puebla, the dish is a symbol of regional pride. Every year on Cinco de Mayo, the commemoration of the Battle of Puebla, Poblanos celebrate Mexico’s victory over Napoleon III’s French army with a feast that includes mole poblano. In much the same way as the victory, the dish remains a source of regional and national unity.

When analyzing the recipe of mole poblano, it is quite evident that at the surface, this concoction of different spices, herbs, and delicacies is a defining cultural staple of modern day Mexico. However, upon deeper inspection, one can visualize the diverse cultures that each of the ingredients in mole poblano represents. Yes, the combination of the ingredients is unique to Puebla despite its disputed creation and origin, but each ingredient is quite the opposite. Each ingredient is a symbol of the culture of the civilization that produced it and can be used to trace the influence of these societies across the globe. It is quite fascinating to me to consider that ingredients found on opposite sides of the world could come together to eventually become the national dish of Mexico.

Making mole is a time-consuming labor of love, usually reserved for special occasions. To make mole from scratch, individual ingredients must be roasted and ground before being combined with stock to form the paste. This is cooked over a low heat, and stock is continuously added (alongside additional ingredients), until it reaches the desired consistency. Several different chilies can be used either alone or in partnership to form the base of the mole, including ancho, pasillo, chipotle and mulato.

When I was experimenting with different versions to make this recipe I decided I wanted to use the permaculture design approach and try to stack some functions.

I decided to experiment with making a more shelf stable and versatile version of Mole Poblano which could be added to other ingredients to make a sauce in a hurry or be used on its own to season things that would not conventionally be enjoyed with Mole Sauce (such as tacos, bean burgers, roasts and bbq-ed main dishes). This is what I came up with

The Mole Poblano Dry Spice Mix

This exuberant spice mix offers vibrant and mysterious flavors.. a steady glow of heat, a hint of floral and the robust and satisfying notes of raw hand ground organic cacao beans.

It can be used as a dry spice rub for bbq-ing, added to stews, chilis and beans and rice or it can be combined with a mixture of other fresh ingredients (which I will show a below) to make a thick and luxurious sauce that can accompany a wide range of dishes.

Ingredients:

2-3 tablespoons cup ancho chile powder (or another mild-medium heat chili of your choice that has been roasted and then dried)

2 tablespoons stone ground cacao nibs/beans

1 tablespoon coconut sugar

1 teaspoon dried chipotle pepper

1 teaspoon ground cinnamon

1 teaspoon allspice

1 teaspoon coriander seed

1 teaspoon ground cloves

1 tablespoon sweet paprika

1 tablespoon dried onions (or dried garlic)

2 teaspoons stone ground whole cumin seed

1 teaspoon black pepper

1 teaspoon dried oregano

Optional ingredients:

- 2 tbsp masa harina (corn flour)

- pinch of sea salt

Directions:

If using whole spices, Pan toasting the cumin seed, black peppercorns, cloves, coriander seed prior to grinding with your mortar and pestle adds additional depth of flavor.

Begin by grinding your cacao beans/nibs (and other whole spices in a mortar and pestle until the pieces are small enough to mix well with the other ingredients.

Combine all the ingredients in a mixing bowl, mix well and then store in airtight containers.

The Mole Poblano Dry Spice Mix will keep for 2 months in the pantry or 6 months in the fridge.

This seasoning is fun to add to bean burgers, tempeh tacos, roasts or bbq-ed items and makes for a great Chili Con Carne seasoning too.

Now that we have the dry spice mix in our repertoire it is time to learn how to make the Mole Poblano Sauce.

It is worth making at least once a year and freezes well so a larger batch can be enjoyed on a handful of occasions throughout the year.

Mole Poblano Sauce

This super nutritious and flavorful sauce goes amazing on anything from the bbq, also great with tempeh, beans and rice or as an interesting dip for shish kabobs.

Ingredients:

- 1/3 cup raisins

- 1/4 cup raw pumpkin seeds

- 1/3 cup pistachios

- 1/2 cup sesame seeds

- 1/4 cup peanuts

- 1/3 cup almonds

- 1/4 cup peanuts

- 3 -4 tablespoons cacao nibs

- 1/4 teaspoon cinnamon

- 1/4 teaspoon allspice

- 1 Ancho peppers

- 1 Mulato peppers

- 1 Pasilla peppers

- 1 onions

- 2 roasted poblano peppers

- 1/3 cup plantain

- 1/4 cup cacao nibs

- 1 teaspoon dried thyme

- 1/2 teaspoon dried marjoram

- 3 dried bay leaves, crumbled

- 1 tomato

- Vegetable broth

- 1 chipotle pepper in adobe sauce

- Corn tortillas

- Small French bread slices

- neutral flavored oil of your choice for frying

- 1/4 cup Dry Mole Spice Mix

Instructions:

Begin by Preparing the Peppers

Stem chiles and shake seeds into a small bowl. Tear chiles into large pieces; set aside. Place 4 tablespoons of reserved chile seeds and sesame seeds in a small cast iron skillet set over medium heat. Toast seeds, stirring occasionally, until lightly brown, about 2 minutes. Transfer seeds to a spice grinder. Add aniseed, peppercorns, and cloves to now empty skillet. Toast until fragrant, about 1 minute; transfer to spice grinder with seeds. Add thyme, marjoram, bay leaves, and cinnamon to spice grinder. Grind all seeds and spices into a fine powder. Transfer to a large bowl; set aside.

Have a large pot ready with simmering veggie broth or water to soak all the ingredients after toasting or frying. They will get softer and easier to grind this way.

Heat oil in a medium skillet over medium-high heat to 350°F. Working in batches, fry chilies until slightly darkened, about 20 seconds per batch; transfer chilies to paper towel lined plate as each batch is finished. Remove skillet from heat and reserve. Transfer chilies to a large bowl and add boiling water to cover. Let steep for 30 minutes. Strain chiles, reserving soaking liquid.

Place the peppers, cacao nibs and the chocolate in the bowl with the broth to soak. Keep toasting the rest of the peppers and placing them in the broth. Meanwhile, toast separately the seeds of the reserved peppers, the coriander seeds, the anise seeds, and sesame seeds. Set them aside to cool.

Working in batches (if necessary) place the chilies, soaking liquid, and veggie stock into blender and purée until as smooth as possible.

Return skillet with oil to 350°F over medium-high heat. One at a time, fry almonds, peanuts, pumpkin seeds, and raisins until toasted, about 1 minute for almonds, 45 seconds for peanuts, 20 seconds for pumpkin seeds, and 15 seconds for raisins. Transfer each batch to a paper towel lined plate as it is done. Transfer almonds, peanuts, pumpkin seeds, and raisins to bowl with spice mixture.

Fry the Mole Dry Spice Mix with the onions until golden brown then add tomato cook until softened and place in the bowl. Fry the tortilla and French bread until crisp. Only add a little more oil at a time or it will be absorbed, especially by the tortilla and bread.

Add the ripe plantain and sauté until golden, about 3 minutes. Using a slotted spoon, drain excess fat and transfer to a bowl.

Now blend everything together. Start by putting ½ cup of the broth into the blender jar. Gradually add the spice mixture and blend well; then add another ½ cup of broth and gradually blend the fried ingredients to a fine paste.

Try not to add more liquid unless necessary but intermittently turn off, mix the contents so the blades get everything evenly with a rubber spatula. You will have to do this step in several batches until everything has been pureed. In a large skillet over medium heat, reheat the sauce, scraping the bottom of the pan very often to avoid sticking. Season with salt.

Continue frying until the mixture is very thick, about 8 minutes, and stir.

Add more broth as needed to desire thickness and continue cooking, the mixture should be bubbling and splattering—for about 25 minutes.

Finally, pour the sauce over your tempeh or chicken and enjoy. Freezes well.

The Regenerative Floating Gardens of The Triple Alliance

Originally, the Aztec empire was a loose alliance between three cities: Tenochtitlan, Texcoco, and the most junior partner, Tlacopan. As such, they were known as the 'Triple Alliance. '

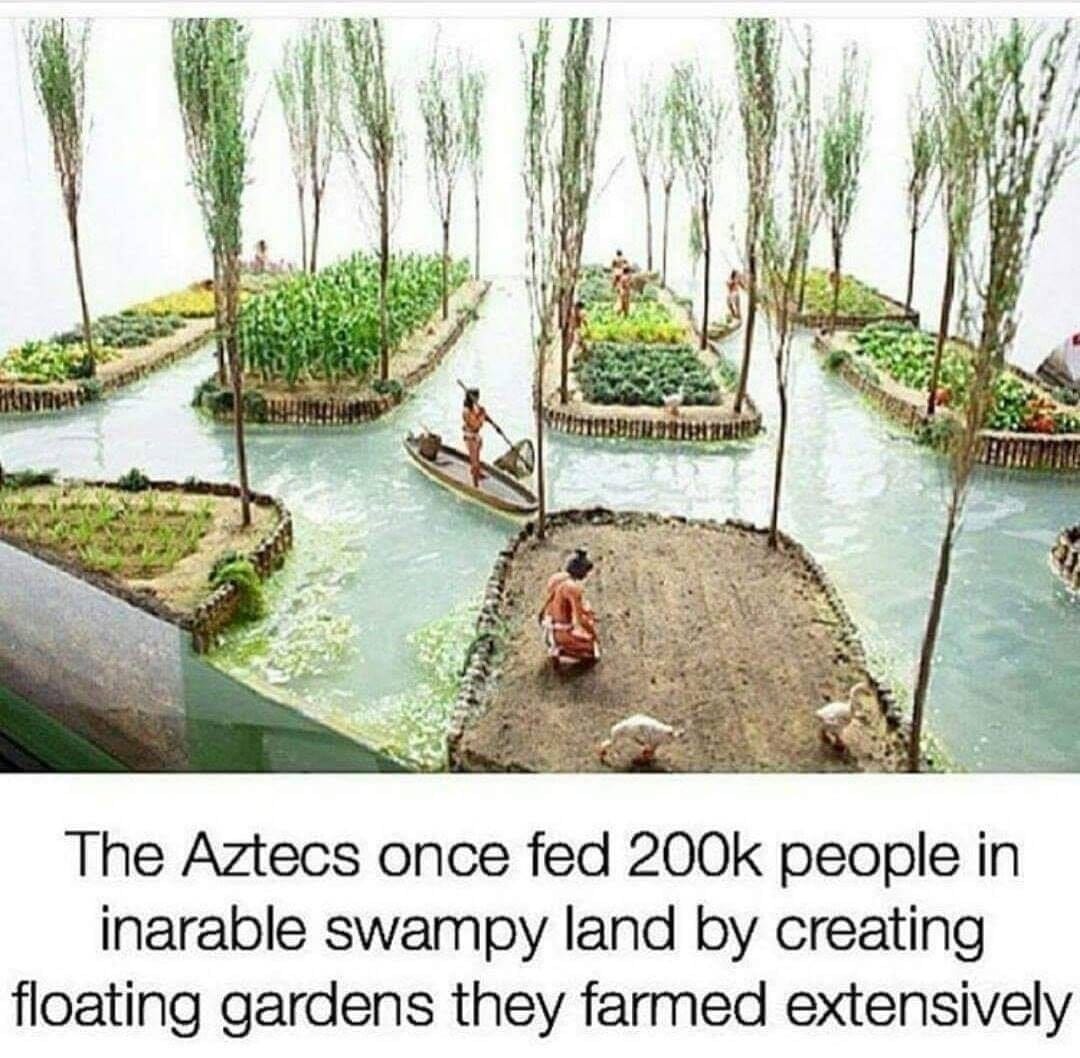

When Hernan Cortez discovered the Aztec Empire in 1519, he found 200,000 people living on an island in the middle of a lake. Tenochtitlan, now Mexico City, was one of the biggest and best-fed cities in the world. The city was completely surrounded by water.

It is also worth noting that the oldest chinampas in the Basin of Mexico date to ca. 1250 CE, well before the formation of the Aztec empire in 1431.

Ancient chinampa systems have been identified throughout the highland and lowland regions of both continents of the Americas, and are also currently in use in highland and lowland Mexico on both coasts; in Belize and Guatemala; in the Andean highlands and Amazonian lowlands. Chinampa fields are generally about 13 feet (4 meters) wide but can be up to 1,300 to 3,000 ft (400 to 900 m) in length.

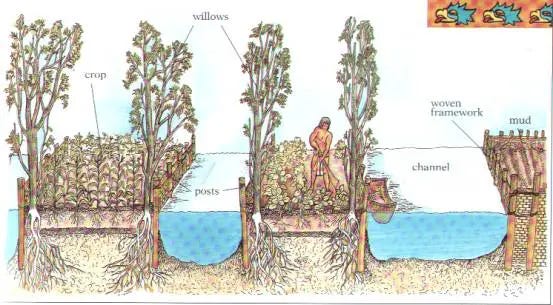

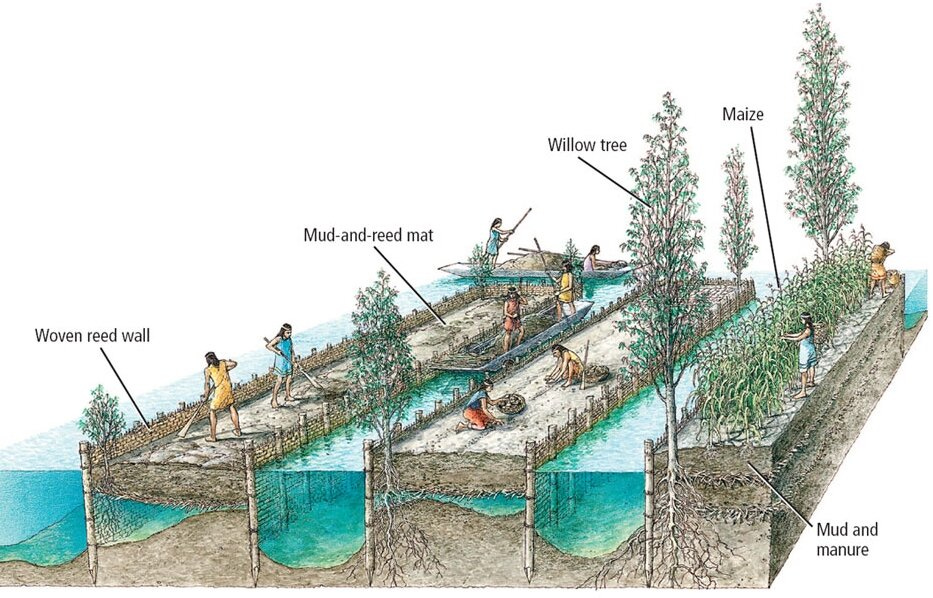

To feed their enormous population, the Aztecs built chinampas, or floating gardens, to convert the marshy wetlands of Lake Texcoco into arable farmland. Each garden was 300 feet by 30 feet. To make a garden, workers weaved sticks together to form a giant raft, and then then piled mud from the bottom of the lake on top of the raft to create a layer of soil three feet thick.

Chinampas are long narrow garden beds separated by canals. The garden land is built up from the wetland by stacking alternating layers of lake mud and thick mats of decaying vegetation. The process is typically characterized by exceptionally high yields per unit of land. The word chinampa is a Nahuatl (native Aztec) word, chinamitl, meaning an area enclosed by hedges or canes.

Chinampas are not just a productive and regenerative agro-ecosystem technique, but they are also representative of the Aztec culture and carry the legacy of indigenous people who taught us how to relate to nature, be part of it and live with it.

The benefits of a chinampa system are that the water in the canals provides a consistent passive source of irrigation. Chinampa systems, as mapped by environmental anthropologist Christopher T. Morehart, include a complex of major and minor canals, which act both as freshwater arteries and provide canoe access to and from the fields.

The World Heritage-listed chinampas remain fecund and ecologically viable even today. These artificial island-farms form one of the most productive agricultural systems in the world as they are incredibly efficient and self-sustaining. That's because the soil is continuously enriched by fine sediments from the lake, plant remains and animal excrement. In addition, the ahuejote fences around each island prevent erosion, protect the chinampa against wind and pests, and act as natural trellises for vine crops. In the early 16th Century, Aztec chinamperos could grow up to seven different crops in a year that resulted in 13 times as much produce as dry land farming.

The most innovative aspect of chinampas, however, is the clever use of water. These narrow islands are packed with porous soil and rich organic matter, which allows them to absorb water from surrounding canals and retain it for a longer period. Additionally, the chinampa layers are designed in a way that allows deep-rooted crops to draw groundwater directly and use it per their needs, thus alleviating the need for external irrigation.

"Chinampas are like giant sponges; you don't need to water them, yet they can be productive all year long," said Lucio Usobiaga, founder of Arca Tierra, a grassroots organisation that works closely with the farmers of Xochimilco to implement regenerative agricultural practices. His team, along with a network of local farmers, has restored more than five hectares of Xochimilco's chinampas over the last 12 years and is committed to producing quality and flavourful food by implementing traditional Aztec technologies, such as companion planting, where mutually beneficial plants are grown close together.

Xochimilco's unique ecosystem of artificial island-farms and nutrient-rich canals also provides safe ecological niches for endemic and migratory aquatic fauna. The chinampas are home to nearly 2% of the world's biodiversity, including the critically endangered axolotl salamander, a marvellous amphibian that possesses the genetic superpower to regenerate every part of its body.

For locals, the chinampas are an expression of their cultural, economic and social identity.

"Chinampas are revered and venerated in our society. Through chinampas, we not only perpetuate the knowledge and traditions of our grandparents but also preserve our relationship with nature that is several centuries old," said Sonia Tapia, agricultural team lead at Arca Tierra.

To maintain the fields, the farmer must continually dredge soil from the canals, and redeposit the soil atop the garden beds. The canal muck is organically rich from rotting vegetation and household wastes. Estimates of the productivity based on modern communities suggest that 2.5 acres (1 hectare) of chinampa gardening in the basin of Mexico could provide an annual subsistence for 15–20 people.

Some scholars argue that one reason chinampa systems are so successful has to do with the diversity of species used within the plant beds. A chinampa system in San Andrés Mixquic, a small community located about 25 miles (40 kilometers) from Mexico City, was found to include an astonishing 146 different plant species, including 51 separate domesticated plants.

For more info on Chinampas, check out this documentary below:

I would like to make it clear that I am not saying the Aztec people were perfect or that we should emulate them in all ways (that is true of all ancient cultures). I feel we can acknowledge how certain practices of ancient cultures were regenerative, ingenious and aligned with integrity while other practices were not (learning from the regenerative practices, honing them using modern methods and discarding the rest). I am sharing the above (and below) info because I advocate for doing what is suggested in The Seventh Fire Prophecy (which involves consciously learning from the wisdom of those that came before as so that we can choose a greener, more abundant, more honorable and more regenerative path in the future). In the spirit of gleaning wisdom from those that came before us to improve the way we produce food and interact with the more than human world I think it is worth exploring the potential for applying the Chinampas growing system in colder climates (so that those of us who live in the temperate zones might also make swampy, boggy land (or lakes) into another space where we can cultivate food in a regenerative way.

Cold Climate Chinampas

The traditional climate for this agricultural system is sub tropical wetland, so there as some factors that need to me taken into account when applying it to colder climate.

The most obvious factor is the effect of winter ice and snow on the system, and how this influences suitable plant and animal species.

One possible advantage of a winter freeze on a chinampa system is the ability to access the growing areas using land based machinery via a way of miniature "ice roads" formed by the frozen canals.

The seasonal glaciation events within the growing areas caused by frost heave introduce an additional mechanism that aids in soil aeration. This action has not been observed in a working chinampa system, and so further research on it's effects could lead to some very interesting findings.

Suitable perennial species of trees and shrubs needs to be identified. The traditional willow that is utilized to reinforce the banks can still be used if a cold hardy species is selected. However, a permaculturist is looking to stack functions...

For bank stabilization and fruit production, pears seem to be an appropriate alternative due to their moisture loving roots and inclination to grow well on river banks. They're also suited to our climate. Although they produce an edible crop, pears do not float, which means that any fruit that falls into the canal will be recycled back into the system as nutrients.

Apples are another option for over story food production and bank stabilization provided that the correct variety is selected for moisture tolerance. Apples also float, and the trees can be trained to form living trellises (see espalier) over the canals onto which vining crops, like cranberry, hops, grapes, and melons can then be grown.

Cranberries will grow in colder climate, and its vining habit means that it can be trained onto trellises over the canals. This makes the additional task of harvesting simple because the fruit floats, and can be simply knocked off the vines into the canal.

In certain zones crops like Goji Berries, Cattails, Nettle, Echinacea and wild rice would be nice options.

Blueberries are also suitable as in nature they will sometimes grow on decomposing logs on the edge of peat bogs. Something to take note of is that hazelnuts also float, and the shrub grows well on canal banks. It is also an excellent coppicing wood and provider of spring bee forage.

It would also be possible to take advantage of the humid environment and close access to water (for forcing fruiting cycles) and to grow medicinal and gourmet mushrooms on hard wood logs as part of a cold climate Chinampa system. This would add an incredible amount of productivity for food and medicine.

Appropriate Nitrogen fixing support species suitable for stabilising the canal banks include seabuckthorn, which produce an edible crop amongst many other functional attributes.

Blue False Indigo is a perennial under-story Nitrogen fixer suited to river bank environments which is loved by bees and can be heavily and repeatedly chopped and dropped. Lupines are an annual under-story Nitrogen fixing plant also loved by bees.

Traditional chinampa involve the creation of annual crop growing beds separated by canals whose banks are stabilised with willow trees.

A modern, cold climate permaculture implementation involves the use of food producing and Nitrogen fixing trees for bank stabilisation and wind breaks. The incorporation of aquaculture, animal systems, and vertical stacking boost the productive capacity of traditional annual crops. Something to consider with regards to the annual crops is the incorporation of Hugelkultur as a way to increase productivity, diversity, and edge zones to the system. Raising crops up off the water table in this way also provides an opportunity to grow plants that prefer dryer conditions than would otherwise prevail.

Additionally, the physical barrier to the effects of wind would create warm, humid micro-climates, and offer the potential to extend the growing season.

Rick Larson has a working demonstration in Wisconsin where he is growing wild rice and blueberries.

This video below is in a zone 5 climate, located in Montana:

For more info on Chinampas and ideas for how they can be adapted and scaled for a range of different climates and situations:

If you liked the content above you may want to check out my book (Recipes For Reciprocity: The Regenerative Way From Seed To Table) which was just released in eBook format.

When you cultivate food in the garden in a way that gives back to the living Earth and honors the many gifts we have been given in this life (including learning from cultural wisdom from those that came before us) you are engaging in the sacred act of Reciprocity.

Using your hands to give back to the Earth and to give thanks to Creator for the gift you have been given in this human body, by taking good care of it with nourishing, delicious and vibrant meals (that use food as medicine and provide poetry for the soul) is a way to give back to your body, your temple and thus a way to give back and say thank you to Creator.

One of the most powerful choices we can make to heal the relationship to Mother Earth, give back to and honor our sacred temple and in doing so engage in an act of Reciprocity begins with a handful of seeds and some TLC.

I am wishing you all a spring time filled with hope, peace, feeling nourished and inspired by the abundance you cultivate and create in the garden and in the kitchen.

That looks yum.

Any great soups, I've been experimenting with Pho last 6 years.

Terrific post!

Mmmmmm.... mole. I had some in Mexico, a few times... you can hardly ever find it in the states, at least not in WA state. ;)

Thanks for all this good stuff!!