Embracing The Abundance Of Spring

This article is intended to help you unlock the springtime bounty of the forest and garden providing info on 23 Springtime foods to harvest in 2024 and beyond!

As the first signs of spring arrive, and winter fades into the rear view mirror, those of us who love to garden will likely be busy planting many of the crops that will sustain us for the rest of the year.

This time of year, after winter stores are almost depleted and before this year’s crops are ready, is traditionally known as the ‘hungry gap’.

Foraging for edible wild plants, however, can help you fill that gap. Wild greens (and some fungi) can be an important source of nutrients at this time of the year.

In this article, we’ll take a look at 23 common edible ‘wild’ plants (and a couple mushrooms) that you can look for around this time.

Many of them you might even find right there on your very own property. Of course, the plants you find will depend on exactly where you live. But you should find some edible wild plants wherever you may be.

Most of us in the modern western world are surrounded in food and do not even know it! Whether we are walking in the forest, an empty lot or in our backyard, many of the plants and trees we see as ornamental, incidental or “weeds” have a long history of being used as food and medicine by those who lived where we now live, many generations before us.

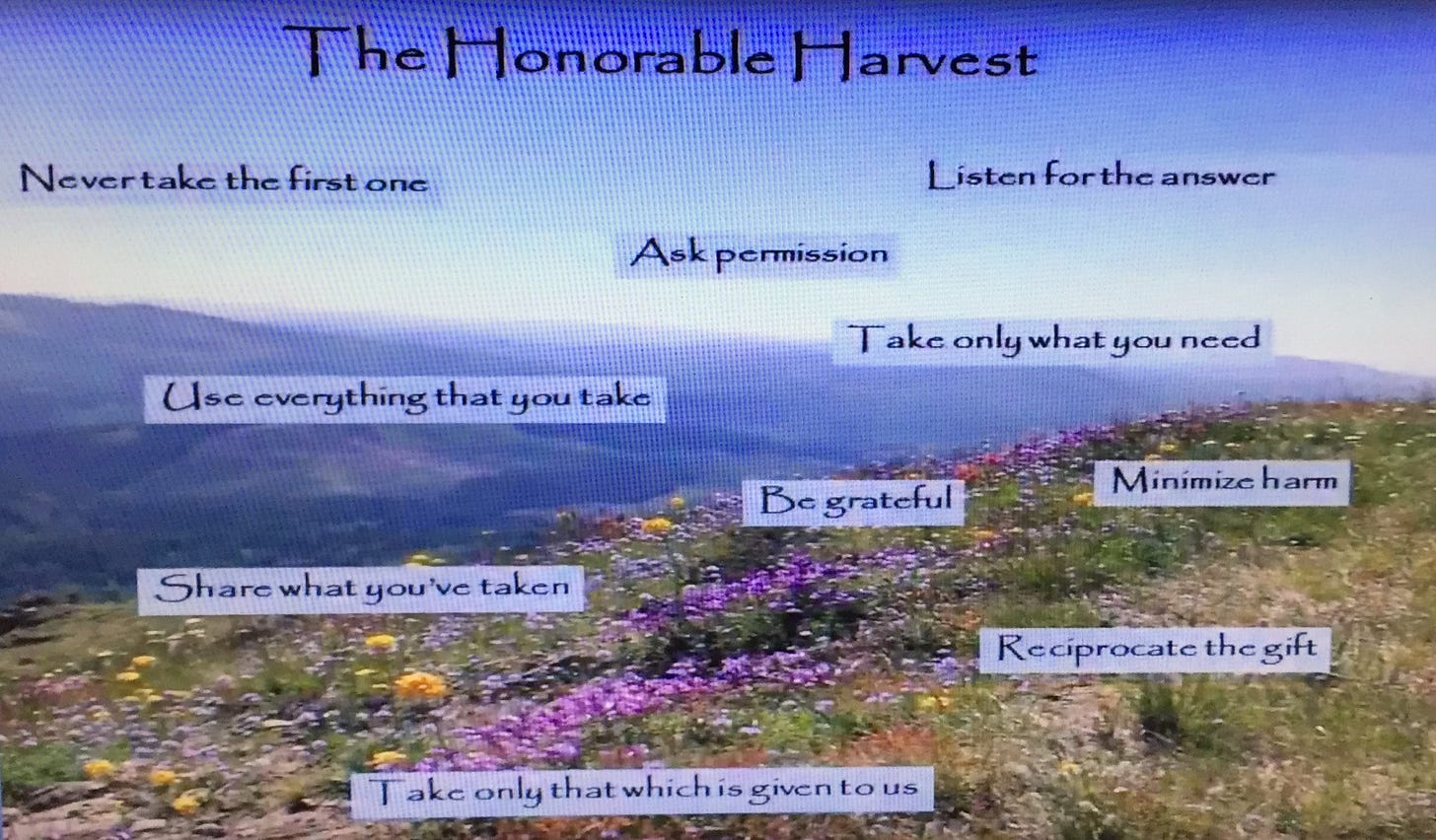

But before we get into what plants and fungi offer their gifts of nourishment and medicine to us (and many other beings) in the spring time, I would like to invoke a recognition of the importance of honoring those gifts (and not harvesting with an anthropocentric mentality) by sharing a quote that speaks to a concept called “The Honorable Harvest”

"The Honorable Harvest, a practice both ancient and urgent, applies to every exchange between people and the Earth. Its protocol is not written down, but if it were, it would look something like this:

Ask permission of the ones whose lives you seek. Abide by the answer.

Never take the first. Never take the last.

Harvest in a way that minimizes harm.

Take only what you need and leave some for others.

Use everything that you take.

Take only that which is given to you.

Share it, as the Earth has shared with you.

Be grateful.

Reciprocate the gift.

Sustain the ones who sustain you, and the Earth will last forever."

-Dr. Robin Wall Kimmerer

An Honest Assessment Of The Current Way Many Humans Live:

It is possible that many modern day city slickers, suburban nose to the grind stone materialistic ladder climbers and rurally situated ipad addicted, credit card wielding, 5 nights of fast food a week central infrastructure dependent people would starve to death (all while being surrounded in a forest or neighborhood full of food) if centralized food production, processing and distribution systems were to collapse (and/or the centralized flimsy financial systems which the food systems depend on collapsed).

Let us now attempt to remedy this ridiculous poverty of plant knowledge and lack of adventurous spirit and explore the wide open world of foraged and fermented wild and (typically) forgotten spring harvests!

Okay now onto the fun part! Let us explore some of the abundant nourishment for the body, mind and senses that springtime in the forest, field or in your backyard has to offer!

Here is a list of some of my favorite spring foods that I like to harvest from the forest and/or in my backyard in springtime:

1. : Hostas

Hostas are edible and delicious. They might be in your garden, but they're also a traditional food in Japan. They taste like a spear of lettuce crossed with asparagus.

Eating hosta's might seem like a novelty but they've been enjoyed in the Far East for a long time. In Japan they're known as Urui, and are described as a type of Sansai: an umbrella term for wild plants that used to be harvested from the mountains.

While most of us in the west think of Hostas as an ornamental plant to fill up those shady areas in our landscape where nothing else will grow easily they are also a near perfect forest garden crop. Woodland is the natural habitat of many hosta species, so they like moist soil with plenty of organic matter and tolerate a considerable amount of shade. A friend tells me that they have a positive allelopathic relationship (i.e. they secrete chemicals that help each other) with apples, and since the research on it is published in Russian I’ll have to take her word for it. Hostas are no novelty nibble: they have the potential to be a major productive vegetable.

The Sansei description is similar to how Northern Latin America (Mexico) uses the term Quelites to describe a number of different small wild plants. Greeks use the word horta as a similar catch-all term for many wild green things.

“Lastly, the most important question. Yes they look cool, yes you can ingest them, but do they actually taste good? I say absolutely, positively yes, they were excellent, I prefer them to milkweed shoots.

All of the hosta species I tried (everything I've read says every species is edible) had a flavor like mild lettuces, the texture is where the money is though.

When the leaves are tightly coiled up they keep a little of their crunch, kind of like a spring onion but without any of the sharpness you would expect from an allium.”

- Alan Bergo (aka The Forager Chef)

Small ones are delicious if you fry them for a few minutes, then add a little light soy sauce and sesame oil. The slight bitterness of the hostons complements the saltiness of the soy sauce very well. Similarly, they go very well in stir fries. The chunkier hostons are better either boiled briefly and used as a vegetable or fermented/pickled.

Later on, the open leaves can be used as a general pot herb or substituted for spinach in recipes like ‘hostakopita’. The flowers and flower buds are also edible: the Montreal Botanical Garden lists all species as edible and Hosta fortunei as the tastiest.

It seems to be an open question whether every single species of hosta is edible and therefore whether it is a good idea to try any unidentified hosta that you may happen across. The species I have eaten regularly myself are H. sieboldiana, montana and longipes. Martin Crawford lists H. crispula, longipes, montana, plantaginea, sieboldii, sieboldiana, undulata and ventricosa. Plants for a Future add H. clausa, clavata, longissima, nigrescens, rectifolia and tardiva and list no known hazards for the genus as a whole. This covers all the common ornamental species except H minor, which probably isn’t worth it anyway, and H fortunei, which must be edible since the most popular variety of it, ‘Sagae’ originally arose in hostas being grown for food in Sagae City in Japan. On the basis of that I’m happy to try any hosta myself.

For more on eating hostas, there is a discussion and some astonishingly beautiful pictures of hosta dishes on the Seed Savers’ Forum. There was also a very useful article in Permaculture Magazine No. 58. It isn’t online unfortunately, but you can buy the back issue if you are really keen. A blogger has also wrote more about eating hostas here.

As noted above, in Japan, hostas are prized as sansai or ‘mountain vegetables’, a class of plants that are usually gathered wild from the mountain and are considered to be particularly strong in vitality. There’s a great blog post about sansai at http://shizuokagourmet.com/sansai/.

2. Fiddlehead Ferns

Fiddlehead ferns are a harbinger of Spring, and, along with ramps and morels they're some of the most widely known and desired spring edibles I look forward to eating every year.

Fiddleheads are fern leaves before they’ve unraveled, and they are usually only available for a few weeks in the springtime.

There's a lot of misinformation and confusion about ‘fiddles’, so I will share info below and explain how to tell different species apart and find fiddleheads that won't make you sick (it's not complicated) as well as show you how you can cook and preserve them.

Habitat

Fiddleheads seem to be pretty much any where I go in the spring with woodsy trails, but my best spots are in areas near water with rich soil and a decent amount of shade. Look for hardwood forests with rich soil, preferably near a river, creek or stream.

The fiddleheads of the Ostrich fern (Matteuccia struthiopteris) are the most popular for foraging, as they are the tastiest. They have a flavor that is similar to asparagus and are excellent sauteed with butter and garlic.

Some other varieties of ferns are also edible as fiddleheads, such as western sword fern, bracken fern, and lady fern. These should all be cooked before consuming.

There's a couple different fiddleheads you can eat (2 or 3 depending on who you ask). Since I am foraging in the eastern woodlands (or my back yard in southern Ontario), my recipes use specifically ostrich ferns or Matteuccia struthiopteris, since I think they're probably the best for the table and they grow near me. Edible Fiddleheads from the West Coast are usually lady ferns (Athyrium filix-femina, a slightly different species that, while still edible, I don't like quite as much as ostrich ferns, but are still great to eat.

Since they're so popular, fiddleheads are commonly overharvested. If you harvest your own, and especially if you harvest from public land, know that it's selfish to take every fern growing from a fiddlehead crown. Take a couple fiddles from a crown, and move along. Think of your harvesting as "thinning" the ferns from a plant, as opposed to clear-cutting, which some do.

Some varieties of ferns are toxic, so be sure that you consult a guidebook and have a positive identification before harvesting.

Read more about foraging and identifying fiddlehead ferns through the underlined link or here.

3. Wild Violet

Wild violets (Viola sororia or Viola odorata) and their leaves are both edible and medicinal. They come up in early spring and are often the first flowers of the season, making them a lovely sight!

They love cooler temperatures and will grow through the winter in warmer locations.

Lots of comparisons get made between wild cooked greens and spinach, plantain and nettles for example, and to an extent I can agree with nettles (I don't care for plantain leaves). Violets are another story.

After cooking, young violet leaves can get quite tender and soft. They're one of the best wild approximations to spinach I've had.

You can also make violet flower infused vinegar, wild violet soap, or violet leaf balm with your foraged violets!

Read more about foraging for wild violets by clicking the previous underlined link or here.

4. Dandelions

Dandelions (Taraxacum officinale) are the quintessential spring foraging plant, with edible and medicinal flowers, leaves, and roots! They are super easy to identify, and any look-a-likes are edible and medicinal as well, so no worries there.

Make dandelion salve with the flowers, dandelion pesto with the leaves, and dandelion root coffee with the roots.

If you’re worried about harvesting dandelion blossoms in the spring because they might be food for bees, it’s actually not as big of a problem as it’s been made out to be.

Dandelions are actually not the best food for bees, and there are many other flowers we should be saving and planting for bees instead! (Read this post on flowers to plant for the bees).

Check out my article on Dandelions for additional nutritional info and fun recipe ideas here:

Read more about foraging for dandelions and foraging for dandelion root here.

Find over 50 ways to use dandelions here.

5. Stinging Nettle

Stinging nettle (Urtica dioica) is one of my favorite plants to forage for in the springtime (both in the garden and in the forest). They are usually pretty easy to find, but don’t forget to bring a pair of gloves for harvesting!

Nettle is a superfood that is packed full of vitamins and minerals. Cooking the plant will dispel its sting.

Make this stinging nettle-ade recipe or these nettle chips with your foraged nettles!

Check out my article on Nettle for additional nutritional info and fun recipe ideas here:

Learn more about foraging for stinging nettle here.

6. Chickweed

Chickweed (Stellaria media) is a tasty edible green that comes up in early spring. In some milder locations it will even grow throughout winter.

Once it warms up chickweed will die back, so be sure to get it while you can so that you can add it to salads or make chickweed pesto!

Read more about foraging for chickweed here.

7. Clover

Both red clover (Trifolium pratense) and white clover (Trifolium repens) are beneficial to us in many ways.

The blossoms are sweet and edible, perfect for adding to baked goods or infusing into honey. Red clover is especially high in vitamins and minerals and makes a wonderful tea.

Make these red clover biscuits or these strawberry white clover cookies!

White clover iced tea is another favorite.

Check out my article on Clover for additional nutritional info and fun recipe ideas here:

Learn more about red clover and white clover and their benefits here.

8. Cattail Shoots and Pollen

Cattails (Typha spp.) are known as the ultimate survival plant, as every part of the plant can be used in some way. Known as Pakwiyeshk and/or Bewiieskwinuk – to the Potawatomi/Ojibwe peoples of the Great Lakes regions in the Anishinaabemowin language. In Potawatomi, the word for cattail, bewiieskwinuk, translates to “we wrap the baby in it” and in the Mohawk language, cattail (Osháhrhe) translates to “the cattail wraps humans in her gifts” as if we were her babies.

The young shoots that come up in the spring are the tastiest part, resembling the flavor of a cucumber, and can be eaten raw.

The yellow pollen that covers the flower spike in late spring or early summer makes a delicious foraged flour substitute.

Make fermented cattail shoots or cattail pollen pasta!

Check out my article on Cattails for additional nutritional info and fun recipe ideas here:

9. Ramps

Ramps (Allium tricoccum) are also called wild leeks and are in the same family as onions and garlic (Allium). They have a strong onion flavor and can be used just like you would use onions or garlic. They grow wild in the eastern United States and Canada.

Where I live, these are a delicious wild vegetable and one of Nature's greatest gifts to foragers (and gardeners that take the time and care to cultivate them at home).

Recipe Ideas:

Please note: wild Ramps require special harvesting practices as they are becoming threatened in many areas. I personally only harvest bulbs (like those shown in the ramp kraut picture above) from the plants I have cultivated in my own garden after I have a well established patch that is spreading beyond the borders of my garden bed. If you dig up a wild ramp, you kill the plant, and it takes 6 to 7 years for ramps to grow and mature.

Ideally, ramp leaves (which, like the bulb, have a rich garlicky flavor and are even more nutritious than the bulbs in some ways) should be cut leaving the bulb in the ground to regrow.

Planting Wild Ramp Seeds as a way to give back and ensure future generations can also share in their gifts.

Ramp seeds are relatively easy to find, and plant.

Go to your patch in the late summer, after the flowers have formed, and find the seed heads. Shake the little black seeds into a container, and bring them with you to plant the next year.

Make sure to toss some seeds around while you're harvesting in the patch to thank the ramps, too.

Dry the seeds on a plate in a dark/dry place, and store in a cool-dry place until they're ready to plant the next spring.

You can also sow seeds into the ground in the late summer or fall when they would fall naturally.

Read more about foraging for, cultivating, preserving and creating in the kitchen with Ramps here and here.

10. Wild Asparagus

Wild asparagus (Asparagus officinalis) is found in patchy areas throughout the United States and Canada and are notoriously difficult to spot.

Habitat:

Instructions on actually finding wild asparagus are rare in foraging literature. Perhaps some writers view the feral sprout as beneath them — it is not a native to North America, after all. Maybe some think it too easy to find, or, so precious they dare not reveal the secret.

Asparagus officinalis, you should know, is precisely the same plant you buy in the store. It is not, strictly speaking, wild. It is feral. Like fennel in California, it has escaped from cultivation in the 400 years since Europeans brought it to Turtle Island.

Now asparagus lives in every state in the United States and every province in Canada, as well as through much of Mexico. So you’d think it would be all over the place, and indeed in a few places it is.

But you still need to actually find the young, tender spears in early spring, when they emerge from a scraggly root crown that can live in excess of 50 years.

When in early spring? As early as February in California, as late as June in Canada. Every region has its indicator. Here it’s when the wild mustard blooms. In other places it’s when lilacs blossom.

When you are ready to start, look for saline or alkaline soil. The patch I pick, in the Suisun Marsh, is a brackish swamp. Moisture is important. Asparagus doesn’t want its feet wet, but wants to be close enough to get the benefit. This can be anywhere in the East and South, but in the arid West, you will need to focus on marsh edges, irrigation ditches and near cattle ponds or sloughs and streams.

If you see salicornia (pickleweed, saltwort, etc), you are too salty. Step back a few feet. In the Midwest — southern Michigan is an exceptionally good place to look for wild asparagus, for example — look around ditches, hedgerows, farm field edges and especially fence lines.

OK, so you are in a likely spot. What to look for?

You’ll know an asparagus spear when you see it, so that’s not a problem. But finding them can be tough. Your best bet is to look for old plants from the previous year. Asparagus is an herbaceous perennial, meaning the growth above ground dies back every year. As a flourishing plant, asparagus is tall, up to 6 feet tall, and ferny, like fennel or dill.

Wild asparagus is just like regular garden asparagus in flavor—which means delicious! Fermented Asparagus & Garlic is one of our favorite ways to enjoy our foraged harvests.

Read more about foraging for wild asparagus here.

11. “Dead Nettle”

Dead nettle got its name because of its supposed resemblance to stinging nettle (I don’t see it) but without the sting.

Purple dead nettle (Lamium purpureum), which is pictured below, is the most common variety and is often found in backyards or gardens. It is perfect to add to a wild greens salad or pesto!

Learn more about foraging for purple dead nettle here.

12. Garlic Mustard

Garlic mustard (Alliaria petiolata) is a prolific plant that is sometimes considered to be invasive. This means that you can and should harvest as much as you want! It has a strong garlicky flavor that is tamed by blanching.

Make this garlic mustard pesto with your foraged greens!

Learn more about foraging for garlic mustard here.

13. Willow

Most everyone is familiar with soft and fuzzy pussywillows that emerge in the springtime. Not everyone knows that willow (Salix spp.) is a highly medicinal tree! White willow bark in particular is a powerful pain reliever—it actually has the same compounds in it as aspirin!

Make willow bark tea to help ease your aches and pains.

Learn more about foraging for willow here.

14. Yarrow

Yarrow (Achillea millefolium) is another highly medicinal plant that comes up in the spring. Its frilly, frond like leaves make it easy to identify. It is also technically edible, but is quite bitter so is most often used for medicinal purposes.

Use yarrow for treating fevers and coughs, or to help stop bleeding. I also have this recipe for wild rose and yarrow soap!

Check out my article on Yarrow for additional nutritional info and fun recipe ideas here:

Read more about foraging for yarrow here and here.

15. Plantain

Plantain is both edible and medicinal, and is a very important herb to know about. There are two main varieties, broadleaf plantain (Plantago major) or narrowleaf plantain (Plantago lanceolata), and both are beneficial.

Young and tender plantain leaves can be eaten raw and are highly nutritious. Older leaves can be added to soups and stews.

Using plantain medicinally is as simple as chewing up a leaf and putting it on a bug bite, bee sting, or minor wound. It stops itchiness and helps to heal wounds. Plantain is also a great herb to use in an herbal salve.

Read more about foraging for plantain here.

16. Spruce/Pine Tips

Spruce tips are one of the best wild herbs available to foragers. Literally the young growth on branches of spruce trees, spruce tips aren't an herb in the typical sense, but, they are for all intents and purposes. Here's everything you need to know.

Spruce tips are one of the best wild herbs available to foragers. Literally the young growth on branches of spruce trees, spruce tips aren't an herb in the typical sense, but, they are for all intents and purposes. Here's everything you need to know.

All spruce species taste different. I worked with some local Amish farmers a few years ago. They'd agreed to sell me spruce tips, but we had to figure out a good tasting species on their property.

Every week for about 3 weeks, they would send me a couple different types of tips from different trees with my vegetable delivery. Eventually we hit on a tasty species before the Spring was officially over, but it took some time.

Perfect tips, at this stage you won't have to remove the paper covering.

Every young spruce tip I've tasted will have a good flavor, but some have intense bitterness too. The goal is to find spruce tips that have the least amount of bitterness or astringency.

No species of spruce is poisonous though, so what you can do is just go around to different trees and taste them until you find one that tastes good.

Like with many foraged foods, you need to be careful with how you treat the trees. Here are some rules to follow when harvesting tips:

always pick from elder, mature trees, young trees need time to grow

never pick more than 20% of the tips from a single tree

never pick tips from the apical meristem, or top of a young tree, which would stunt it's growth

That being said, spruce tips are one of the most easy to harvest and easily regenerated things you can forage.

As I mentioned, each species of spruce tip is going to taste a little different. Some will have a strong citrus note to them, some will taste a bit bitter.

All the types I've had have a strong piney-citrus note to them, but some have more of the astringency than others. Let your palette be your guide here. By far, my favorite species to cook with so far are:

White Spruce (Picea glauca)

White Pine (Pinus Strobus)

Blue Spruce (Picea pungens)

Norway Spruce (Picea abies)

Spruce tips have a fantastic shelf life. Picked fresh and cooled, they can last for multiple months under refrigeration at a restaurant, or a few weeks at home.

I store spruce tips in a plastic bag with a damp paper towel to help hold in moisture.

I share additional info on foraging for spruce tips, pine tips, pine cones, spruce cones and other edible Conifer tree parts in this article:

17. Ground Elder (Aegopodium podagraria)

Some people are put off eating this wild edible because they try a mature leaf, and do not care for the rather strong and unusual taste.

But here is the trick – pick the leaf shoots when they are very young, soon after they emerge in the spring and before the leaf has even unfurled.

Pick the leaf stem as low down as possible – this is the main part you want. Then simply stir fry it in olive oil to bring out its pleasing flavour.

Young leaves have a parsley like flavour and can also be used as a pot herb. Nip off flower heads as they form to keep the seeds from forming, and also to keep the plants producing tasty leaves for longer.

Check out my article on Ground Elder for additional nutritional info and fun recipe ideas here:

18. Fat hen / Lambsquarter

Chenopodium album goes by many names. It is known as fat hen, lamb’s quarters, and a number of other regional names.

In spring, the young leaves of this plant may be eaten raw (in moderation) but are best cooked. They are mild tasting and a little bland, but make a very acceptable substitute for spinach in a range of recipes. This plant is actually eaten as a staple in parts of South America, Asia and Europe. It is in the same plant family as spinach, quinoa and amaranth.

Check out my article on Lambsquarters aka Fat Hen for additional nutritional info and fun recipe ideas here:

19. Henbit (Lamium amplexicaule)

Henbit is sometimes confused with purple dead nettle (and the two plants are closely related). Both are members of the mint family. The main way to tell them apart is by their leaves. Henbit has heart-shaped leaves, while purple dead nettle’s leaves are more triangular in shape. Henbit’s leaves grow along the whole length of the stem, while purple dead nettles frow in clumps.

As the name suggests, chickens love to eat this plant. But it is great for humans to eat too. The mild and slightly sweet leaves work very well in a salad, and like purple dead nettle, they can also be cooked as a general purpose green vegetable, or used as a potherb.

Henbit can be consumed fresh or cooked as an edible herb, and it can be used in teas. The stem, flowers, and leaves are edible, and although this is in the mint family, many people say it tastes slightly like raw kale, not like mint. It is very nutritious, high in iron, vitamins and fibre. You can add it raw to salads, soups, wraps, or green smoothies.

For more info on foraging for “henbit” click here.

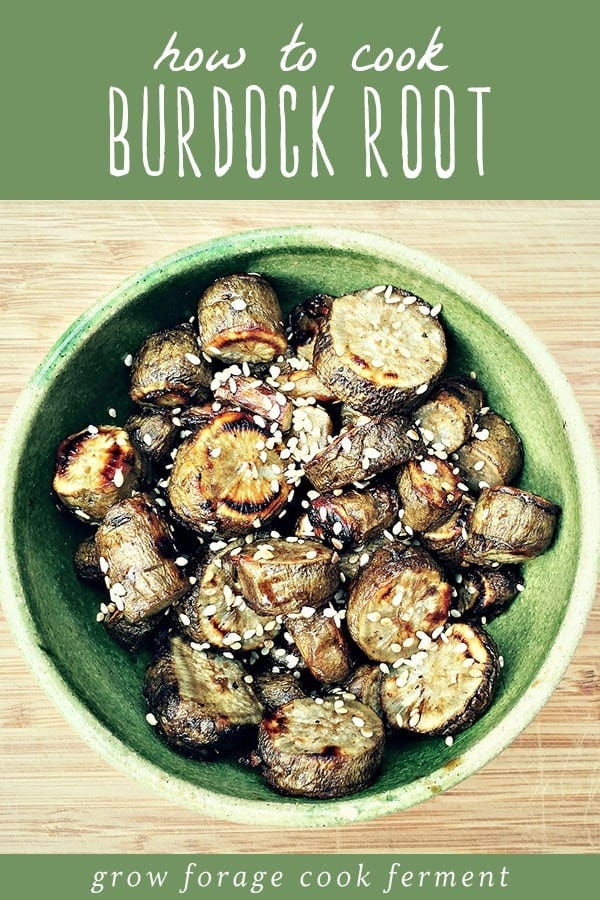

20. Burdock (Arctium sp.)

Burdock is commonly used as a herbal medicine. But it is actually a useful wild edible too. Burdock may be most familiar to you as the plant with those annoying little burrs that get stuck to your clothes.

You may have also heard of the drink, dandelion and burdock. But you may be surprised to learn that you can also eat the leaves, stalks and roots.

In very early spring, you can see young burdock seedlings emerging from the soil before much else has sprung up. The leaves are bitter, but can be used as a pot herb and are less bitter while they are still small. Burdock root can also be harvested.

Burdock roots are usually long and fairly thin, with a brown skin. They are in the thistle family, same as the artichoke, of which they have a similar flavor.

It may not be the most common vegetable around, but if you see burdock root at your local market, you should buy some just to see what it’s all about.

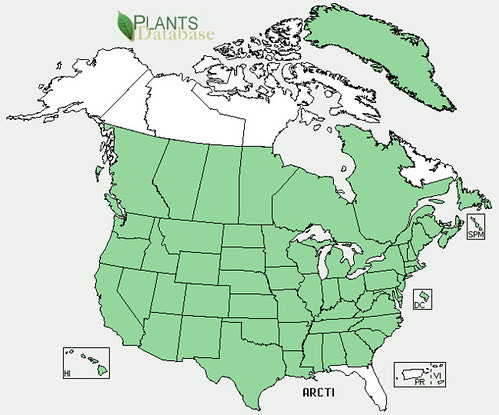

Burdock is also easily foraged as the plant grows wild in most of Canada and the U.S.

Burdock root is an awesome food source, full of vitamins and minerals!

Burdock root, also known as gobo, is popular in Asian dishes. It works very well in stir fries, braises, and soups.

Burdock root can also be peeled, sliced and eaten raw out of hand or on a salad. It resembles a radish with a slight artichoke flavor when eaten this way.

For more info on foraging For Burdock for food and medicine click here.

21. Morel Musrhooms

My grandparents used to get me to help them forage for morels on Galiano Island (near their restaurant) in BC, so I have very fond memories of the good harvest years when we would harvest, sauté and share a morel feast with their customers.

Morels are some of the best mushrooms to forage for in the springtime!

Be sure to use a mushroom guidebook whenever you are out mushroom hunting.

Morels should be cooked before eating and can be used like any other mushroom in recipes. Try them simply sauteed or even deep fried!

Morel mushrooms or Morchella are a kind of edible wild mushrooms found in the hardwood forests of the Northern Hemisphere; from Arctic/subarctic North Americas to Siberia. Morels are one of the highly prized mushrooms, valued for their rarity, and savory flavor.

Morels grow in fertile organic, moist, and sandy soil. Completely developed morel mushroom measures about 6 inches in height. In the subarctic coniferous forests, they typically foraged during the spring season in the woods wildfire areas burnt during the preceding summer. In the hardwood forests, they found in abundance around the base of elm, ash, aspen, cottonwood, and oak trees.

Health benefits of morel mushrooms:

Morels, fresh or dried, are low calorie mushrooms. 100 grams carry just 31 calories. Nonetheless, they endowed with superb levels of health benefiting antioxidants, essential minerals and vitamins.

1. Morels carry the highest amount of vitamin-D among the edible mushrooms. 206 IU or 34% daily required levels of vitamin-D in 100 grams of raw morels, mostly in the form of ergocalciferol (vit.D-2). This fat-soluble vitamin is labeled as "hormone" for its role in the bone growth, and calcium metabolism.

2. Morels are unique among the wild edible mushrooms which recognized for their rich mineral content. 100 grams of raw morels carry 69%, 152%, 26%, and 18% of copper, iron, manganese, and zinc levels respectively.

3. Copper is one of the essential trace element that functions as co-factor for many oxidative enzymes involved in cellular metabolism. It is also required for blood cell production (hemtopoiesis), and neurotransmission.

4. 100 g of morel mushrooms carry 194 mg or 28% RDI of Phosphorus, and 43 mg of calcium. Adequate calcium, phosphorus and vitamin-D levels in the blood is critical for the growth and development of bones and teeth.

5. Zinc is essential nutrient that plays a vital role in cellular metaboilsm, mucosal regeneration, immune function, and reproductive organ growth.

6. Additionally, these mushrooms are an excellent source of the B-complex group of vitamins such as niacin (14% of RDA per 100 g), riboflavin, pantothenic acid, and vitamin B-6 (pyridoxine). Altogether, these vitamins work as co-factors for enzymes during cellular substrate metabolism inside the human body.

7. Antioxidants:

Oxidative stress is associated with numerous conditions, such as cardiovascular disease, Parkinson’s disease, and diabetes types 1 and 2. Consuming antioxidant-rich food, therefore, is an important strategy to protect against this internal damage.

Studies have shown that extracts from morel mycelium are effective in combating oxidation. This is primarily accomplished through the scavenging of damaging molecules known as reactive oxygen species (ROS), including the superoxide, hydroxyl, and nitric oxide radicals.

Antioxidants from morel mushrooms have also been shown to inhibit lipid peroxidation – a process involving tissue damage which, if left unchecked, can lead to inflammation and cancer.

8. Liver protection

Carbon tetrachloride (CCl4) is an inorganic compound which has been linked to disorders of the central nervous system and kidneys. Research on animals has shown that administration of CCl4 with ethanol damages the liver by, among other things, depleting internal antioxidant stores. When supplied with an extract of morel mycelium, however, protection is provided against liver damage, and antioxidant reserves can be restored.

This suggests that morel mushroom mycelium may provide therapeutic use as a liver-protecting agent.

9. Immune system activity

A 2002 study analyzed the immuno-stimulatory property of a unique polysaccharide isolated from the morel mushroom. Known as galactomannan, this compound comprises 2.0% of the dry fungal material, and may work on both innate immunity and adaptive immunity by enhancing macrophage activity.

Learn more about foraging for morel mushrooms here.

22. Oyster mushrooms (Pleurotus ostreatus)

Oyster mushrooms have been used for thousands of years as a culinary and medicinal ingredient. The white mushrooms resemble oysters, and can be found growing in the wild on dead trees or fallen logs. They have a rich history in traditional Chinese medicine from as early as 3,000 years ago, particularly as a tonic for the immune system.

This species will grow spring through fall in many locations.

They are relatively easy to identify because they always grow on trees or stumps (if it’s not growing from a tree, fallen log, or stump, it’s not an oyster mushroom!). They are also some of the tastiest wild mushrooms around.

Be sure to use a mushroom guidebook whenever you are out mushroom hunting.

Here are some of the health benefits of Oyster mushrooms:

1. Antioxidant Effects:

Oyster mushrooms contain ergothioneine, a unique antioxidant exclusively produced by fungi, according to a 2010 study led by Penn State food scientist Joy Dubost. The study found that oyster mushrooms have significant antioxidant properties that protect cells in the body. A 3 oz. serving of oyster mushrooms contains 13 milligrams of ergothioneine, and cooking the mushrooms does not reduce this level.

2. Anti-Bacterial Effects:

Oyster mushrooms have significant antibacterial activity, according to a 1997 study published in the "Journal of Agricultural and Food Chemistry." The study found that the active compound benzaldehyde reduces bacterial levels. It may form on the mushroom as a reaction to stress.

3. Nutritional Value:

There are 42 calories in one cup of oyster mushrooms, making them a low-calorie addition to any meal. Oyster mushrooms are also high in nutrients. According to a study published in "Food Chemistry," oyster mushrooms contain significant levels of zinc, iron, potassium, calcium, phosphorus, vitamin C, folic acid, niacin, and vitamins B-1 and B-2. The study concluded that consuming oyster mushrooms as part of a healthy diet contributes to recommended nutritional requirements.

4. Helps modulate blood cholesterol levels:

Because of their native lovastatin content, oyster mushrooms have been studied for their benefits in helping modulate blood cholesterol levels.

5. Anti-cancer compounds:

While oyster mushrooms remain an excellent source of natural lovastatin, their medicinal attributes extend well beyond cardiovascular health. In the International Journal of Oncology, Jedinaki and Silva (2008) idenitified two molecular mechanisms from alcohol extracts of oyster mushrooms that "specifically inhibits growth of colon and breast cancer cells without significant effect on normal cells, and has a potential therapeutic/preventive effect on breast and colon cancer." Moreover, in the same cell culture tests, these alcohol-soluble extracts of oyster mushrooms out-performed similarly prepared extracts from button (Agaricus bisporus), shiitake (Lentinula edodes) and enoki (Flammulina velutipes) mushrooms -- three species more extensively studied for their immune-supporting properties. These mushroom extracts up-regulate genes coding for p53 and p21 proteins, which in turn stop tumors from growing and support tumor regression. Additionally, the non-alcohol soluble beta glucan and glycoprotein complexes found in oyster and other medicinal mushrooms alert the immune system's natural killer and cytotoxic T cells, improving the body's natural anti-cancer responses. For cancer researchers interested in mushroom use in complementary therapies, the possibility that oyster mushroom consumption can improve cancer treatment using distinctly different but synergistically powerful pathways should be cause for serious consideration. Many more mushrooms are likely to activate and up-regulate these genes for coding cancer-limiting proteins.

Learn more about foraging for oyster mushrooms here.

23. King Bolete (Porcini)

King boletes (Boletus edulis), also known as porcini mushrooms, are considered a delicacy in many places for good reason: they’re delicious!

“Spring Kings” are often found growing in the forest duff underneath conifer trees, and they start to emerge in the springtime. King boletes will also commonly grow in the late summer and fall after rainfall.

Boletes can sometimes be tricky to identify, be sure to use a mushroom guidebook whenever you are out mushroom hunting.

Learn more about foraging for king bolete (porcini) mushrooms here.

Okay that is all for today, now it is time to get out there and get foraging and creating!

Happy harvesting and have an awesome day my friends!

-----------------------------------

For more info on foraging for/cultivating and enjoying springtime foods:

Food from your Forest Garden (by by Martin Crawford and Caroline Aitken)

“In Food From Your Forest Garden, Martin Crawford lists more than 120 forest garden plants which crop between February and May, including: fruits, nuts, salad leaves, vegetables, flowers, bulbs, roots, tubers, herbs and spices. This impressive collection of trees, shrubs and herbaceous plants clearly demonstrates not only an uninterrupted, but a diverse harvest, the like of which the annual vegetable garden could never achieve.”

The Healing Trees ( by Robbie Anderman)

“By moving off-grid to a farm in the Wilno Hills of Eastern Ontario, Robbie Anderman left behind his former way of life, his allergy shots and pills, and the social supports that he was used to. He quickly discovered that he needed to learn how to live on the land that had become his home.”

The Forager Chef‘S Book of Flora : Recipes and Techniques for Edible Plants from Garden, Field, and Forest (by Alan Bergo, a.k.a Forager Chef)

“..A new way to think about vegetables. Don’t throw away your carrot tops! Learn how to use all parts of the plant from bud to root. The book is the first in a series that will also include fungi and fauna.”

Stalking the Wild Asparagus (by Euell Gibbons)

“Euell Gibbons sought out wild plants all over North America and turned ordinary fruits and vegetable into delicious dishes. His book includes recipes for vegetable and casserole dishes, breads, cakes, muffins and twenty different pies. Plus jellies, jams, teas, and wines, and how to sweeten them with wild honey or homemade maple syrup.”

Tending the Wild (by M. Kat Anderson)

“Much of California was pristine, untouched wilderness before the arrival of Europeans. But as this groundbreaking book demonstrates, what Muir was really seeing when he admired the grand vistas of Yosemite and the gold and purple flowers carpeting the Central Valley were the fertile gardens of the Sierra Miwok and Valley Yokuts Indians, modified and made productive by centuries of harvesting, tilling, sowing, pruning, and burning. Marvelously detailed and beautifully written, Tending the Wild is an unparalleled examination of Native American knowledge and traditional reciprocal land management practices in California's that reshapes our understanding of indigenous cultures and shows how we might begin to learn from their knowledge in our own conservation efforts. M. Kat Anderson presents a wealth of information on indigenous land management practices gleaned in part from interviews and correspondence with Native Americans who recall what their grandparents told them about how and when areas were burned, which plants were eaten and which were used for basketry, and how plants were tended. The complex picture that emerges from this and other historical source material dispels the hunter-gatherer stereotype long perpetuated in anthropological and historical literature. We come to see California's indigenous people as active agents of environmental change and stewardship. Tending the Wild persuasively argues that this traditional ecological knowledge is essential if we are to successfully meet the challenge of living regeneratively.”

- https://fearlesseating.net/fiddleheads/https://fearlesseating.net/fiddleheads/

- https://foragerchef.com/lacto-fiddlehead-pickles/

- https://foragerchef.com/hosta-shoot-kimchi/

For more information on the principles of the Honorable Harvest (which I touched on above see:

"The honorable harvest is a covenant of reciprocity between human beings and the living world, and these guidelines were taught to me as a plant harvester when I would go out to pick berries, or to pick medicines, with wise teachers. This is what they told me.

One of the first things is when you come out to the berry patch or get out to the woods is You never take the first one. Because it might be the last one. It’s an ethic of self-restraint that has inherent conservation values. Different people have different rules about this – sometimes you don’t take until you’ve seen four, or five, or seven. But you wait. You restrain yourself.

And then, if we encounter that next plant. you talk to the plant. Ask permission. You introduce yourself to the plant. Tell it who you are, what you have come for. What is it you need from those berries or from that medicine. If you are going to take a life, you need to be personally accountable for that transfer of life.

If you are going to ask the question, you better listen for the answer. You can listen in different ways. You can look around empirically and judge whether the plants are numerous enough and healthy enough to support your harvest. There are also ineffable ways to listen and find out what they are saying to you. And if the answer is no, it’s no. You go home. You go home empty-handed because we remember that they do not belong to us. Taking without permission is stealing.

And if you are granted permission, the honorable harvest says take only what you need, and no more. And this is a very difficult step in our materialistic, affluence-plagued society where the difference between our wants and our needs is blurred. We’re all encouraged to take everything that we get.

The honorable harvest also says you take in ways that do the least harm and that do the most to benefit the growth of the plant. You don’t use a shovel if a digging stick will do.

Use everything that you take. It’s disrespectful of a life that you take to waste it. And we have forgotten this easiest lesson – to have everything that you need is not to waste what you have.

Be grateful. Give thanks or everything that you receive. In an economy that urges us to always want more, the practice of gratitude is truly a radical act. Thankfulness for all that is given makes you feel rich beyond measure, where wealth is counted as having enough to share. Gratitude pulls us into relationship with other entities, reminding us that our very existence is in their hands. And gratitude is humbling – an antidote to the arrogance of our time. It reminds us that we are just one member in the democracy of species. It reminds us again, that the earth does not belong to us.

The next tenet of the honorable harvest is to share what the earth has shared with you so we model that behaviour in return. A culture of sharing is a culture of resilience, that can endure these waves of plenty and scarcity that come to us.

And lastly, and perhaps most importantly, reciprocate the gift. If you take from the earth, in order for balance to occur, you have to give back. We have forgotten this. Even our definitions of sustainability, are all about trying to find a formula by which we can keep on taking. We say our job as humans is not to ask what more can we take from the earth, but what can we give back in return, for the gifts of the earth.

I don’t think what we need today is more data, more studies, new technology, or more money, but an ethical shift. A change in the story that we tell ourselves about our relationship to the living world. We need acts of restoration, not only for polluted waters and degraded lands. We need a restoration of honor. An honor that we can all choose in the daily way we live – ethics made in daily decisions. So when we walk through the world, we don’t have to avert our eyes in shame, but hold our heads up high and receive respectful acknowledgement of all the other beings, in return. And the reward is not just a good feeling. It could save our lives."

-Dr. Robin Wall Kimmerer

I hope you found this information helpful and will try foraging for some of the abundance offered to us in springtime by our Mother Earth. She invites us to find peace of mind in the knowing that we are surrounded in food and medicine.

If we learn from Mother Nature and accept her open hand we can thrive and nurture our bodies in any and all situations (while staying guided by integrity and love).

We can align our wealth and health with the health and wealth of the living Earth and through merging with her regenerative capacity and inherent abundance we can become irrepressible.

We can lift ourselves and our communities out of the widespread modern day ‘poverty of plant knowledge’ and in doing so become resilient enough to survive and thrive no matter what life throws our way.

Each and everyone of us is capable of choosing (as our ancestors did) to develop and intimate and reciprocal relationship with the wild plants, trees and fungi in our local region. It is my hope that this article offers you some sign posts that empower you to feel confident on the path ahead.

May each of us find our footing and hope through embarking on the soft and green path described in The Prophecy Of The Seventh Fire.

In closing I will share a blessing passed down by my ancestors…

May the blessed sunlight shine upon you; May Light shine out from your eyes like a lamp set in the window to welcome the wanderer out in the storm. May the blessing of the rain be yours; may it beat upon your spirit and wash it clean, leaving a shining pool where the Truth of the Mother herself glows. May the blessing of the Earth be on you; soft under your feet as you pass along the path, soft under you as you lie out on it, tired at the end of day; and may it rest easy over you when, at last, you lie out under it.

Mother Nature sure provides for us, and you honor her by sharing your plant wisdom so generously, Gavin. I'm blessed to have many of these amazing "weeds" growing all around me. I'm just starting to meander out there looking for them. I still have some snow but every day it's less and less. I can see Queen Yarrow sending her little fern-ey leaves up through the ground. Makes my heart so happy to see. :) Happy Spring nibbling! 🌿💚

Love your note on the hostas! So much abundance out there.