Paw Paw (Asimina triloba)

Exploring the many gifts offered by Paw Paw trees the in the context of Food Forest Design. This is Installment #6 of the Stacking Functions in the Garden, Food Forest and Medicine Cabinet series.

Pawpaw is an unbelievable tree and fruit. Imagine a fruit the size of a mango, that smells like the most exotic tropical fruit. Cutting it in half reveals an incredibly sweet, rich, custard-textured flesh that has a flavor profile somewhere between banana, papaya, pear, strawberry and jackfruit. And you picked it from a tree on YOUR land! For our region, where winters can get to -26 C and heavy winds, it is a very special experience to have such a tropical seeming tree. The foliage and bark are not desired by deer or rabbits, so we find we can plant paw paw out with no browse pressure.

The pawpaw is a cousin to the custard apple and cherimoya, the only member of the tropical sugar apple family living in the temperate north. Basically, the pawpaw is a tropical fruit tree that hitchhiked its way north as the continental glaciers receded at the end of the Ice Age. The pawpaw is now found growing indigenously, primarily throughout the eastern United States and very southern part of Ontario. This amazingly adaptive fruit tree has become so popular that it is being introduced into many other temperate regions of the globe.

This stunning tree grows in partial shade (it desires shade in its youth), and can tolerate Black Walnut trees with grace.

The PawPaw is a tree that is so wild and unique and wonderful, and yet, is often quite unknown. Paw Paw is an underappreciated and under-recognized tree. Within the bushcraft and permaculture circles, it is quite well known as an amazing tree to find, plant, and tend.

One of the reasons that PawPaw is probably not more well known has, unsurprisingly, everything to do with the commercial viability of the fruits. PawPaw fruit is absolutely delicious but it only stays good for a few days after picking–so it would never survive the rigors of modern industrial agriculture. You can occasionally find it at a good farmer’s market, and it is well worth seeking out! You can also seek it out in the wilds. PawPaw is the only large fruit producing tree that grows wild in a north-eastern climate.

This leads to the names for the PawPaw, which includes everything from Appalacian banana, Michigan Banana, Ozark Banana, Kentucky Banana, West Virginia Banana, to American custard apple, Quaker delight, hillbilly mango, and poor man’s banana. As you can see from some of these names, a bit of a stigma was once attached to PawPaw, which may be another reason it is not as sought out or well known. Such are the long term impacts of the type of food snobbery and big ag propaganda that I touched on in this radio segment.

Family: Annonaceae

Part used for medicine/food: Fruit (pulp as food) , leaves, bark and seeds (for making various medicinal extracts to be applied carefully).

Constituents: acetogenins, analobine, asiminine.

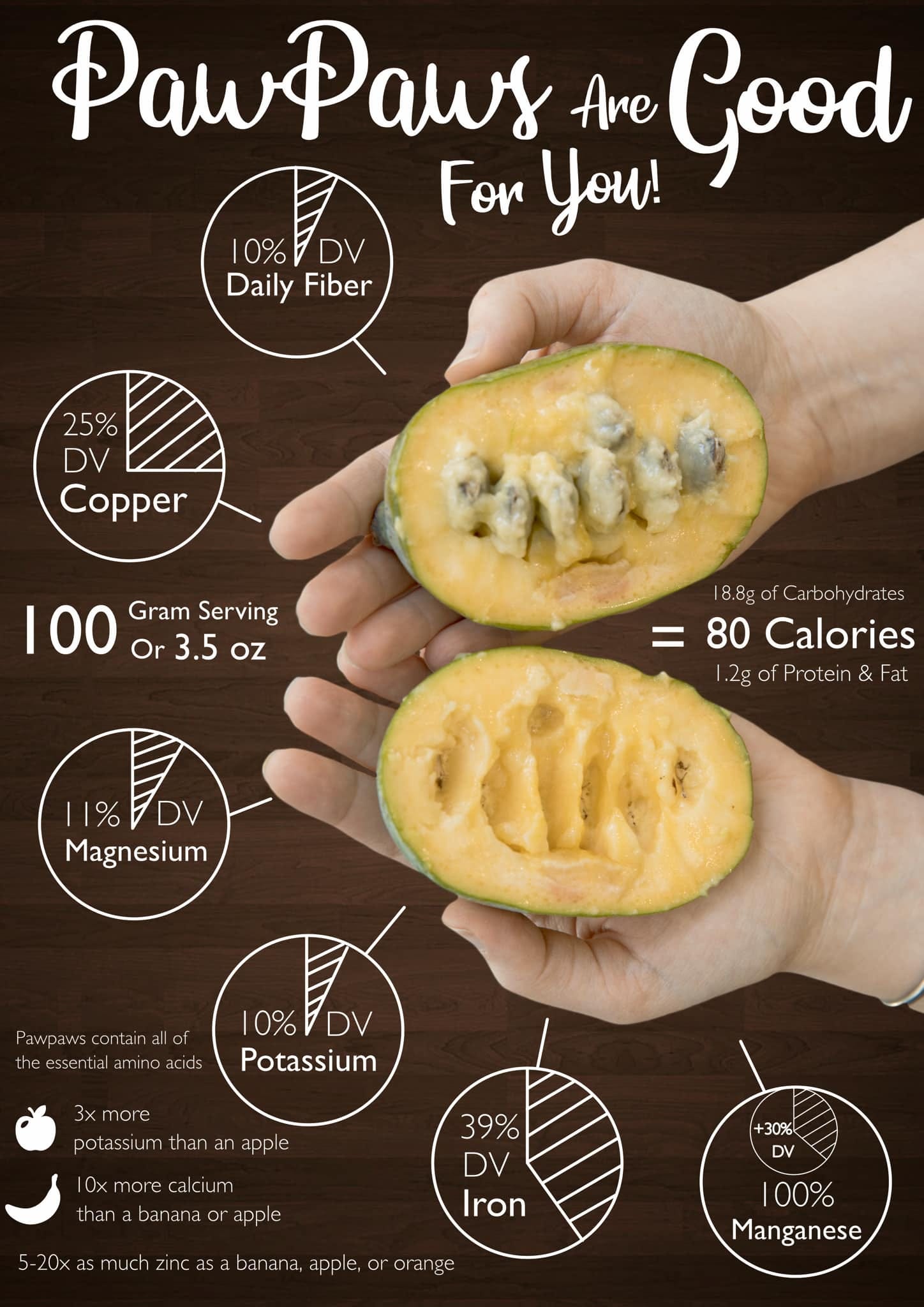

Nutritionally speaking, pawpaws are vitamin-packed antioxidant powerhouses. Pawpaw pulp protein contains all essential amino acids in contents higher than that of apples, bananas, or oranges.

Full of vital vitamins and minerals, exceeding peaches, grapes and apples. It is exceptionally high in potassium, calcium, vitamin C, niacin, phosphorus, iron, zinc, copper, and magnesium.

Also high in antioxidants (epigallocatechin, epicatechin and p-coumaric acid) and unsaturated fatty acids.

Medicinal actions: antiangiogenic, antimicrobial, antioxidant, antiproliferative, cardioprotective and tonifying.

Pawpaw (Asimina triloba) contains acetogenins that can inhibit the growth of cancer cells.

The seeds of the Pawpaw contain an alkaloid, asiminine, which has antiproliferative emetic properties. The compound also supresses tumor Angiogenesis. The fruit is used as a laxative, leaves are diuretic, and are applied externally to boils, ulcers and abscesses. They have been powdered and applied to hair to kill lice. It has also been used in homeopathy as a remedy for scarlet fever and red skin rashes. The bark is a bitter tonic and contains the alkaline analobine, which is used medicinally. The Pawpaw made headlines in 1992 when a Purdue University researcher isolated a powerful anti- cancer drug, as well as a safe natural pesticide from the Pawpaw tree. The substances are said to be primarily found in the twigs and small branches, and is among the most potent and least toxic anti-cancer agents currently known.

Pharmacology: Pawpaw (Asimina triloba) contains acetogenins that inhibit the growth of cancer cells.

Leaf essential oil of Asimina triloba (L.) Dunal (F. Annonaceae) is active against both human lung carcinoma and breast carcinoma cell lines.

Antioxidants in this fruit can delay the aging process and help optimize cardiovascular function.

Cold Hardiness: 4 - 9

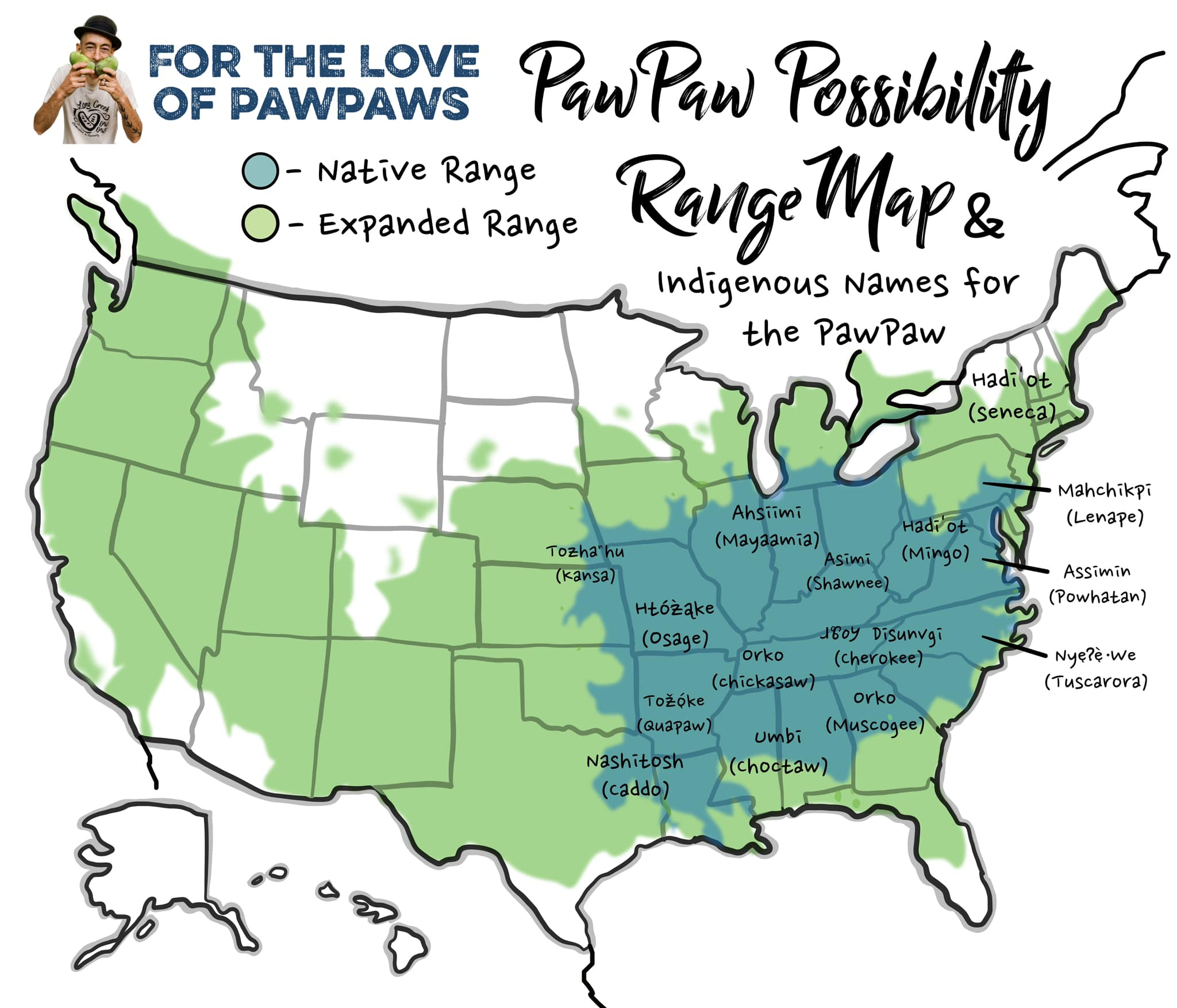

Native (and possible) Range:

If any of you are in the range shown in the map in the pic below, you are a paid subscriber to my Substack newsletter, and you would like to attempt to create your own Refugia to help this species begin to gain a foothold in the wild (or increase in numbers) where you live you can leave a comment or email me at recipesforreciprocity@proton.me and i`ll put you on the list for seeds that will be harvested from our (hopefully) abundant 2024 crop.

Growth Form:

Sometimes reaching up to 12 m (40 ft) in height but typically, roughly 25’ tall and 15’ wide.

Grown in full sun, the pawpaw tree develops a narrowly pyramidal shape with dense, drooping foliage down to the ground level. In the shade it has a more open branching habit with few lower limbs and horizontally held leaves. Leaves large, green, simple, alternate 17.8-25.4 cm long, elliptical to oblanceolate, spread out in umbrella-like whorls, entire, and papery, emit a strong tomato or green pepper smell when crushed.

Flowers cup-shaped, up to 5 cm wide, first green, turning deep reddishpurple (3 green sepals and 6 purple petals in two tiers), not showy but fragrant. The species name, triloba, refers to the calyx (the outer most flower whorl, made up of the sepals), which consists of three triangularshaped sepals. Fruit oblong, large edible berry, 5-16 cm long and 3-7 cm wide, weighing 20-500 g, with numerous seeds; green when unripe, maturing to yellow or brown, aromatic, the yellow pulp soft and sweet, blending the flavors of banana and custard with a lovely texture reminiscent of the avocado. Twigs stout with naked red-brown hairy buds. Bark thin, smooth, dark brown, often with gray blotches and small wart-like projections on older trees.

Reproduction:

Pawpaw flowers are perfect, but not self-pollinating requiring cross pollination from another unrelated pawpaw tree. Pollination is by blowflies and carrion beetles which are not always efficient and dependable causing poor fruiting in some regions.

The bloom period is about 6 weeks during March to May (spring) followed by the fruit in summer. The fruit ripens between mid August into October during with harvesting is done. It reproduces clonally and less often from seed, forming patches in the understory.

Habitat and Ecological Niche:

An understorey tree of woodlands, growing in deep rich moist soils of river valleys and bottomlands, often forming dense thickets.

Pawpaw does well in naturalized, riparian, or woodland areas.

A. triloba is a tree of temperate humid growing zones, requiring warm to hot summers, mild to cold winters and is almost always found in nature as an understory tree of rich broadleaf deciduous forests growing in bottomland areas, on wooded slopes, ravines, along streams and in marshy areas with deep, rich, damp, sandy, or clayey acidic soils and high rainfall.

In full sun, a pawpaw tree takes on a beautiful 15-to-25-foot tall pyramidal shape. It can also grow in the forest understory or forest edge; however, fruit production and form are best in full sun.

In the dense shade of the woodlands, pawpaws typically sucker to form in a patch. The height of the pawpaw in the forest varies depending on soil and light availability; in poor soils and low light, trees typically reach a maximum height of six- to eight-feet tall.

Here is a video from that same forest:

This stunning tree grows in partial shade (it desires shade in its youth), and (as stated above) can tolerate Black Walnut trees with grace. 2 trees minimum for pollination, under 10 trees will probably require hand pollination since the carrion fly is it’s main pollinator.

Soil type: prefers a slightly acid soil (pH 5.5-7), deep, fertile, and well-drained. Pawpaws do not thrive in heavy or waterlogged soil.

Common tree associates include blackgum (Nyssa sylvatica), Aesculus glabra), honey locust (Gleditsia triacanthus), and Kentucky coffee tree (Gymnocladus dioica).

Health Benefits of Paw Paw fruit (pulp)

pawpaws may even come with some serious health benefits — similar to the benefits of pineapple — and could help protect against bone loss, anemia, high blood sugar levels and more.

Nutrition Facts

Pawpaw fruit is a great source of several important nutrients, including manganese, copper, iron and magnesium.

A 3.5-ounce serving of pawpaw fruit (approximately 100 grams) contains about:

Calories: 80

Total Carbohydrates: 18.8 g

Fiber: 2.6 g

Total Fat: 1.2 g

Saturated Fat: 0.4 g

Polyunsaturated Fat: 0.3 g

Monounsaturated Fat: 0.5 g

Trans Fat: 0 g

Protein: 1.2 g

Manganese: 2.6 mg (113% DV)

Copper: 0.5 mg (56% DV)

Iron: 7 mg (39% DV)

Magnesium: 113 mg (27% DV)

Vitamin C: 18.3 mg (20% DV)

Zinc: 0.9 mg (8% DV)

Riboflavin: 0.1 (8% DV)

Potassium: 345 mg (7% DV)

Niacin: 1.1 mg (7% DV)

Calcium: 63 mg (5% DV)

Health Benefits:

1. High in Antioxidants

Antioxidants are compounds that can help protect cells against free radical damage, and pawpaws are high-antioxidant foods. Some research has found that antioxidants may play a key role in overall health and could aid in the prevention of chronic conditions, like autoimmune disorders, heart disease and cancer.

Pawpaws are loaded with powerful antioxidants that can help support better health. In fact, one in vitro study analyzed the pulp of the pawpaw fruit and found that it contained several antioxidants, such as epigallocatechin, epicatechin and p-coumaric acid.

2. Blocks Problematic Microbial Growth

In addition to their antioxidant content, pawpaws may also possess potent antimicrobial properties as well. According to a study published in Journal of Food Science, pawpaw extract was able to block the growth of Corynebacterium xerosis and Clostridium perfringens, two strains of pathogenic bacteria that can cause illness and infections in humans.

3. Helps Prevent Iron Deficiency Anemia

Pawpaws are a great source of iron, an important nutrient that is involved in the production of healthy red blood cells. A deficiency in this key micronutrient can cause iron deficiency anemia, a condition characterized by weakness, fatigue, brittle nails and shortness of breath.

Not only that, but pawpaws are also high vitamin C foods, packing 20 percent of the recommended daily value in each 3.5-ounce serving. Vitamin C boosts the absorption of iron in the body, which can help protect against iron deficiency anemia.

4. Preserves Bone Health

Each serving of pawpaw fruit is loaded with nutrients that are important for maintaining bone density and preventing issues like osteoporosis. Manganese, for instance, is involved in bone formation and can help keep bones strong.

Several other minerals found in pawpaws can also help prevent bone loss. In fact, some studies show that taking manganese with copper, zinc and calcium — all of which are found in pawpaw fruit — can effectively reduce bone loss in older women.

5. Promotes Better Blood Sugar Control

Pawpaw fruit is rich in manganese, which is an important micronutrient that plays a central role in maintaining blood sugar control. Promising research even suggests that adding more manganese to your diet could potentially aid in the prevention of type 2 diabetes.

According to an animal model published in Endocrinology, supplementing with manganese was found to protect against diabetes by enhancing the secretion of insulin, a hormone that helps transport sugar from the bloodstream to the cells. What’s more, one study of nearly 4,000 people found that manganese levels were significantly lower in those with type 2 diabetes, suggesting that manganese may be involved in regulating blood sugar levels.

6. Supports Healthy Digestion

With 2.5 grams of fiber packed into each serving, adding pawpaw fruit to your diet can help support better digestive health as a high-fiber food. This is because fiber moves through the body slowly, adding bulk to the stool to prevent constipation and promote regularity.

In addition, increasing your intake of fiber can also enhance the health of the gut microbiome while also protecting against digestive conditions like hemorrhoids, diverticulitis, stomach ulcers and acid reflux.

The phytonutrients in the fruit also help with digestion.

7. Kills Lice

Pawpaw has popped up in several shampoo and skin care products recently, and for good reason. In fact, research suggests that pawpaw extract could help effectively eliminate lice to relieve symptoms like itching and scratching.

A 2002 study out of Spanish Fork, Utah evaluated the effects of an herbal shampoo containing pawpaw extract on lice and nits, or lice eggs. According to the study, the shampoo was 100 percent effective at removing lice and nits in 16 people when applied topically.

8. Reduces Cancer Cell Growth

Studies suggest that pawpaw could be as effective as other fruits, such as soursop, to help reduce the growth of cancer cells in vitro.

Two studies, published in two separate journal articles in 1997, showed that the pawpaw compounds not only are effective in killing tumors that have proven resistant to anti-cancer agents, but also seem to have a special affinity for such resistant cells. The findings were detailed in the journal Cancer Letters and the Journal of Medicinal Chemistry. (big thanks to

for the heads up on this info).For instance, one test-tube study found that pawpaw extract was able to block several signaling pathways that are key to cancer growth. Meanwhile, other research indicates that pawpaw contains specific compounds like acetogenins, which can inhibit the growth and spread of cancer cells.

Another study determined that “pawpaw extracts are natural therapeutic agents that may be used for the prevention and treatment of gastric and cervical cancers, and encourage further studies on the anti-inflammatory potential of the pawpaw tree.”

History and Cultural Relevance of Paw Paw:

Archaeological data demonstrates the significance of pawpaw to early Indigenous diets. As food writer and gardener Andrew Moore writes, “Pawpaw seeds and other remnants have been found at archaeological sites of the earliest Native Americans, and in large, concentrated amounts, which suggests seasonal feasts of the fruit.” According to Moore, “whether at Meadowcroft or the rugged hills of Arkansas, the earliest Americans put pawpaws to great use.”

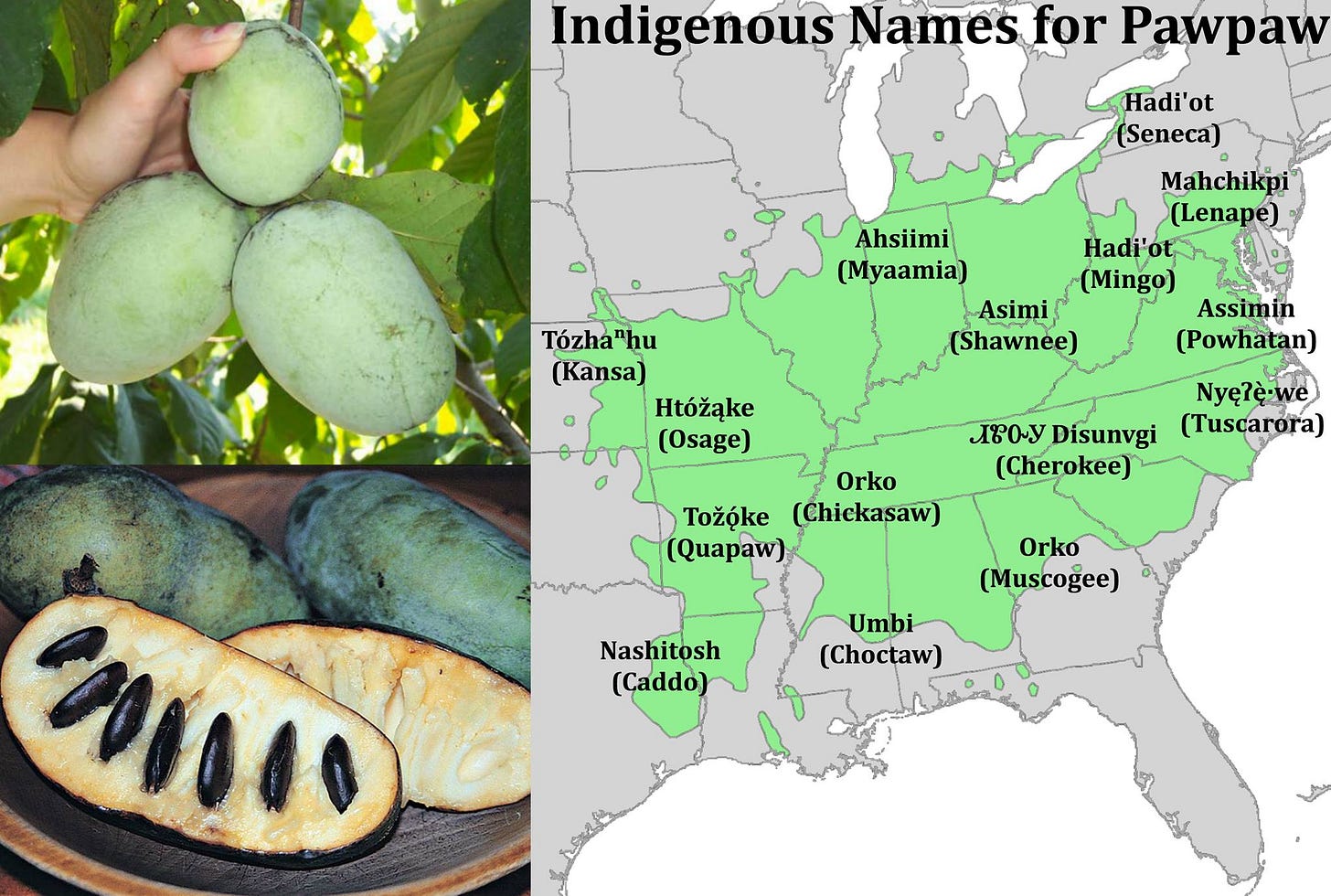

The genus name Asimina comes from the Ojibwe word for pawpaw 'aazimin' or 'aasimin' and is in the Magnoliales order.

Pawpaw’s importance to Indigenous peoples in America is reflected not solely archaeologically, but in folklore and linguistics. As Moore notes, “the town of Natchitoches [Louisiana] translates to ‘the pawpaw eaters,’ and is derived from the place-name given by the Caddo, who called pawpaw nashitosh.” Joel Barnes, language and archives director for the Shawnee tribe (and tribal member) told West Virginia Public Radio, “The word for pawpaw is ha’siminikiisfwa. That means pawpaw month. It’s the month of September…That literally means pawpaw moon.”

Pawpaw was commonly cultivated as an important food source by First Nations (people indigenous to Turtle Island) People, but that waned as people were removed from their land. Pawpaw gained popularity with settler communities for a time, but the mismanagement of woodlands & sprawling farmland limited it's preferred habitat. By the 20th century it fell into obscurity.

The earliest written report of pawpaw was made in 1541 by a Portuguese officer who was a member of Spaniard Hernando de Soto’s expedition through the southeastern United States. He noted Native Americans growing and eating pawpaws in the Mississippi Valley region (Pickering 1879; Sargent 1890): “There is a fruit through all the country which groweth on a plant like Ligoacan [possibly a reference to lignum vitae, Guaiacum officinale], which the Indians do plant. The fruit is like unto Peares Riall [“pears royal”]; it has a very good smell, and an excellent taste” (Hackluyt 1609). Apparently, the name pawpaw was given to the tree by the members of the de Soto expedition for the resemblance of the fruits to the tropical fruit papaya (Carica papaya) that they already knew (Sargent 1890), papaya being a Spanish word derived from the Taíno word papaia.

In some English speaking countries, such as Australia and New Zealand, the tropical papaya is also known as pawpaw, often resulting in confusion between the two species. After this first report, pawpaw was described in records from additional explorations of the United States. One quote about the pawpaw in the northern United States is found in the so-called de Cannes memoir of 1690 (Pease and Werner 1934), probably written by Pierre Deliette, a French trader and colonial official who lived for several decades in Illinois: “There were other trees as thick as one’s leg, which bend under a yellowish fruit of the shape and size of a medium-sized cucumber, which the savages call assemina. The French have given it an impertinent name. There are people who would not like it, but I find it very good. They have five or six nuclei [seeds] inside which are as big as marsh beans, and of about the same shape. I ate, one day, sixty of them, big and little. This fruit does not ripen till October, like the medlars.” In 1709, John Lawson, a British explorer, reported in his book A New Voyage to Carolina—probably the first report of pawpaw in English—that “The Papau is not a large tree. I think I never saw one a foot through; but has the broadest leaf of any tree in the Woods, and bears an apple about the bigness of a hen’s egg, yellow, soft, and as sweet as anything can well be. They [the Indians] make rare puddings of this fruit” (Lawson 1709).

Dr. Devon Mihesuah is a professor at the University of Kansas, a citizen of the Choctaw Nation, and also a Chickasaw descendent. She has devoted her life to recovering lost knowledge of indigenous foods. ‘I have spent decades taking a look at travelers' reports, people who observed back in the 1700s, coming through,’ she said. ’Nobody ever mentioned pawpaw. They just say this strange fruit. They didn't know what to call it.’ (Choctaw word for pawpaw is umbi.) She has not found any traditional pawpaw recipes among the Choctaw, who called the Mississippi Valley and Southern Appalachia home before they were forced West. She says there's a reason for that. Like a banana, the pawpaw has a short window of ripeness. That meant it was probably consumed right on the spot--a convenient, fast food. They would just wait until the time to eat it because they don't store well‘ she said.

It is believed that Indigenous people, including the Erie and Onondaga, introduced the tree to Southern Ontario from the United States.

In 1749, the Jesuit priest Joseph de Bonnecamps described the pawpaw: “Now that I am on the subject of trees, I will tell you something of the assiminetree, and of that which is called the lentil-tree. The 1st is a shrub, the fruit of which is oval in shape, and a little larger than a bustard’s egg; its substance is white and spongy, and becomes yellow when the fruit is ripe. It contains two or three kernels, large and flat like the garden bean. They have each their special cell. The fruits grow ordinarily in pairs, and are suspended on the same stalk. The French have given it a name which is not very refined, Testiculi asini. This is a delicate morsel for the savages and the Canadians; as for me, I have found it of an unendurable insipidity” (Thwaites 1899).

Besides these early reports, it is known that George Washington planted pawpaws at this home, Mount Vernon, in Virginia (Washington 1785). Pawpaws were also among the many plants that Thomas Jefferson cultivated at Monticello, his home in Virginia (Betts et al. 1986); during his time as Minister to France he had pawpaw seeds (Jefferson 1786) and plants (Jefferson 1787) shipped to his friends in Europe.

In September 1806, the members of the Lewis and Clark expedition subsisted almost entirely on wild pawpaws for several days. William Clark wrote in his journal : “Our party entirely out of provisions. Subsisting on poppaws. We divide the buiskit which amount to nearly one buisket per man, this in addition to the poppaws is to last us down to the Settlement’s which is 150 miles. The party appear perfectly contented and tell us that they can live very well on the pappaws” (Lewis and Clark 1806). Daniel Boone and Mark Twain were also reported to have been pawpaw fans (Pomper and Layne 2005), and early settlers also depended partially on pawpaw fruits to sustain them in times of crop failure (Peterson 1991). Pawpaws are well established in American folklore and history (the traditional American children’s song, “Way down yonder in the pawpaw patch,” is still popular) and several towns, creeks, and rivers have been named after this fruit tree.

Traditional Cajun application of this plant is as a laxative- tea of the leaves and/or fruit eaten; Leaves also used as a poultice for unspecified reasons but further research documents that the leaves (in poultice form?) are applied externally to boils, ulcers and abscesses. White milky sap of the unripe pawpaw contains a high percentage of papain, which is used for chronic wounds or ulcers. The Cherokee ate the fruit and also used the inner bark to make ropes and string. The Seminole are documented as using an infusion of the flowers to treat kidney disorders.

Although few people today have never even heard of pawpaws, they were actually believed to have been a favorite dessert of George Washington at one point.

What’s a Cultivated Pawpaw? A Short Story: In the simplest terms, plant cultivation—or breeding—combines natural selection with artificial selection and cultivation. For example, if you lived a thousand years ago out in the Ohio River valleys where pawpaw groves naturally flourished, you would have taken note of those trees with big tasty fruit in abundance, and would not have chopped them down to harvest the fibrous inner bark to make footwear, baskets, etc. Rather, you would have cut down the trees with small, dinky, seedy fruits and fashioned some stylish pawpaw clogs, thus beginning the process of informal plant breeding.

Zoom forward approximately 900 years to the time of the early European settlers, and you’d find farmers who, while out hunting raccoons, discovered some impressive pawpaw fruits and saved the seeds and marked the productive trees. Back at the homestead, they might plant the seeds near the house or alongside the corn and tobacco fields. Over time, the best resulting trees—with good fruit and consistent yields—are kept and the inferior pawpaws are cut down. Among these selected prime producers, one tree really shined for strength of growth, balance of productivity, and fruit quality, so it gets named after a beloved aunt called “Matilda.”

The reputation of Matilda starts getting around and by and by a fruit explorer, who we’ll call Wyatt, comes to the homestead toward winter’s end to see the famed tree. Impressed, Wyatt takes eight-inch cuttings of last year’s growth from the branch ends (known as scion wood) that he carefully wraps in a moist cloth, and heads onward to the next rumored pawpaw tree of repute.

In early May, Wyatt gets back to his property in Maryland where he has young pawpaw trees growing from local seed. He sets to grafting the collected branch ends of Matilda onto his local rootstock. Four years later, Wyatt is able to taste the first fruits of his labor. Although impressed, he waits and watches how the tree strengthens over another decade to be sure Matilda is stable in productivity, health, and fruit quality. Once Wyatt is sure he has a bona fide specimen, he writes about it in a horticultural journal and offers others to come to his homestead to collect scion to graft onto their pawpaw trees. And thus, a new cultivar is born.

It does not need to take a thousand years to breed a new cultivar. Neal Peterson, affectionately known as the Mahatma Pawpaw, has spent his life’s work researching and creating some of the most consistently productive and tasty pawpaw cultivars available. Neal was able to breed seven outstanding cultivars in roughly 20 years, though, granted, he was using the genetics of his ancestors from which to launch his studies.

In 1916, the American Genetics Association sponsored a contest seeking both the biggest pawpaw tree and the best pawpaw fruit. Fifty bucks to the winner of each category. In today’s dollars, that’s the equivalent to $1,000 each. Criteria were focused on flavor, seed number and size, and how well it held up during shipment. The fruits and photos poured in, over 450 pawpaws, from a wide range of states. The winner of best fruit came from Mrs. Frank Ketter of southeastern Ohio. The Association deemed Mrs. Ketter’s pawpaw fruit a fine specimen with mild, yet rich, flavor, a good amount and quality of flesh, and of good shipping quality. Alas, not much came from the competition to further the breeding and selecting of quality fruit; however, the genetics of the prize-winning Ketter pawpaw was taken up by famed horticulturist David Fairchild, who planted the seeds at his home in Chevy Chase, Maryland. From the seedlings, he chose the best specimens, which he then named “Fairchild”—after himself!

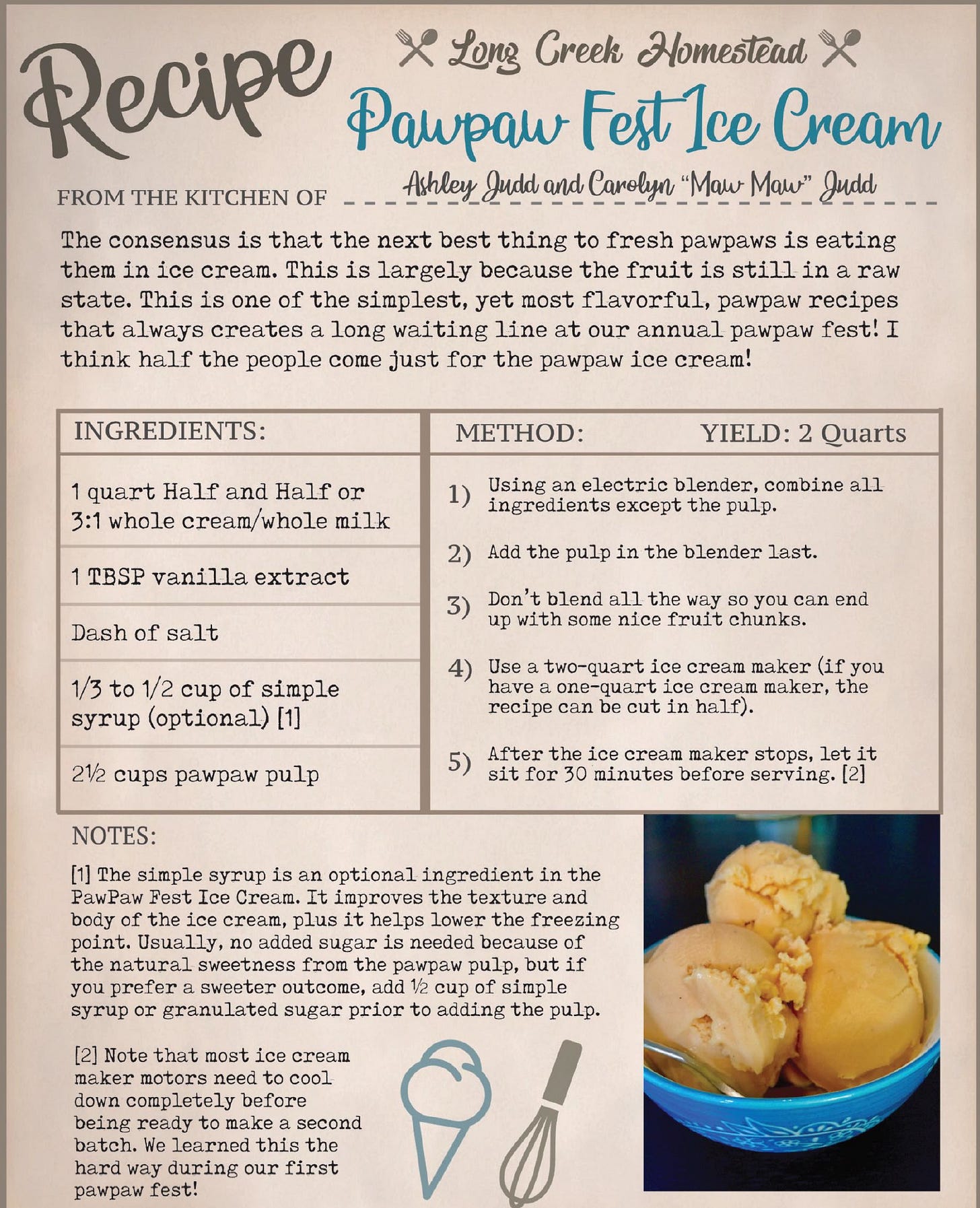

Because of their soft texture and sweet flavor, they are often enjoyed raw or chilled. They are also added to many dessert recipes and can be used to make ice cream, sorbet or jam.

Functions In The Wilderness and in the Food Forest:

Pawpaw in Permaculture Design

Permaculture design is all about creating sustainable and self-sufficient ecosystems. In this context, the Pawpaw tree is a valuable asset. Its ability to thrive in various soil conditions, its tolerance to shade, and its deep-root system make it an excellent choice for permaculture gardens. The Pawpaw tree’s large, umbrella-like leaves provide ample shade, creating a microclimate that can benefit other plants in the garden. This shade can help to reduce water evaporation from the soil, maintaining soil moisture levels and reducing the need for watering.

Pawpaw’s Contribution to Soil Health

The Pawpaw tree also contributes significantly to soil health. Its fallen leaves decompose and enrich the soil with organic matter, improving soil structure and fertility. This process of natural composting recycles nutrients and promotes the growth of beneficial soil organisms, contributing to the overall health of the garden ecosystem. Furthermore, the tree’s deep roots help to prevent soil erosion, an important factor in maintaining soil health and productivity.

Another significant advantage of the Pawpaw tree in permaculture design is its natural pest resistance. The tree contains acetogenins, compounds that have insecticidal properties. These compounds deter many common garden “pests”, reducing the need for chemical pesticides. This natural form of pest control aligns perfectly with the principles of permaculture, which emphasize working with nature and minimizing harm to the environment.

Pawpaw as a Food Source

Of course, one of the most appealing aspects of the Pawpaw tree in a permaculture setting is its fruit. The Pawpaw fruit is not only delicious but also highly nutritious, providing a valuable food source for both humans and wildlife. The fruit can be eaten fresh or used in a variety of recipes, from Pawpaw bread to Pawpaw ice cream. Having a Pawpaw tree in your garden ensures a yearly harvest of this unique fruit, contributing to food security and self-sufficiency.

Pawpaw’s Role in Polycultures

In permaculture, polycultures (the growing of multiple crops in the same space) are favored over monocultures. Polycultures mimic natural ecosystems, promoting biodiversity and resilience. The Pawpaw tree fits well into polycultures. Its shade can benefit shade-tolerant plants, its fallen leaves provide mulch, and its flowers attract pollinators, benefiting other flowering plants.

Pawpaw’s Companions

Pawpaw trees, with their large, spreading leaves, create a significant amount of shade. This makes them an excellent companion for plants that thrive in partial shade. Some potential companions for Pawpaw could include understory plants like currants, gooseberries, and ginseng. These plants can benefit from the shade provided by the Pawpaw tree, especially in regions with hot summers.

Benefits of Pawpaw as a Companion Plant

The benefits of Pawpaw as a companion plant extend beyond providing shade. The tree’s fallen leaves decompose to enrich the soil with organic matter, benefiting nearby plants. Additionally, the deep roots of the Pawpaw tree can help break up compacted soil, improving soil structure and making it easier for the roots of companion plants to penetrate the soil.

Furthermore, the Pawpaw tree’s natural pest resistance can also benefit its companion plants. The acetogenins in the tree’s leaves and bark deter many common pests, reducing the overall pest pressure in the garden.

Pawpaw and Polycultures

As part of a polyculture, Pawpaw trees can contribute to the overall health and resilience of the garden ecosystem. They can help create a layered structure in the garden, with taller trees like Pawpaw providing a canopy for lower-growing plants. This layered structure mimics natural forest ecosystems and promotes biodiversity.

Incorporating Pawpaw into your food forest not only provides you with a source of delicious and nutritious fruit, but also enhances the overall health and diversity of your garden. In the following section, we’ll delve deeper into how Pawpaw contributes to biodiversity.

The Pawpaw tree, with its unique characteristics and benefits, contributes significantly to the biodiversity of a permaculture garden.

Pawpaw’s Contribution to Plant Diversity

In terms of plant diversity, the Pawpaw tree adds a unique element to the garden. Its large, tropical-looking leaves, its unusual flowers, and its distinctive fruit are unlike those of most other temperate fruit trees. This visual diversity can make the garden more enjoyable for humans, but it also has practical benefits. Different types of plants attract different types of beneficial insects and birds, promoting a balanced and healthy ecosystem.

Pawpaw and Animal Diversity

The Pawpaw tree, native to North America but now cultivated in various parts of the world, including Scandinavia, plays a significant role in supporting animal diversity. Its flowers attract a variety of insects, including several species of flies and beetles, which are crucial for pollinating the Pawpaw flowers. These insects, in turn, serve as food for birds and other creatures, contributing to a diverse food web.

Pawpaw and Soil Biodiversity

The benefits of Pawpaw to biodiversity extend below the ground as well. The tree’s deep roots help to improve soil structure, creating spaces for air and water that are essential for soil organisms. The fallen leaves of the Pawpaw tree decompose and contribute to the organic matter in the soil, providing food for a variety of soil organisms. These organisms, including bacteria, fungi, and earthworms, play a crucial role in nutrient cycling and soil health.

Pawpaw and Ecosystem Health

By contributing to plant, animal, and soil biodiversity, the Pawpaw tree enhances the overall health and resilience of the garden ecosystem. A diverse ecosystem is more stable and less susceptible to pests and diseases. It’s also more productive and more sustainable in the long term.

Incorporating the Pawpaw tree into your permaculture garden not only provides you with a source of delicious and nutritious fruit, but also contributes to the biodiversity and overall health of your garden. In the next section, we’ll provide practical tips on how to incorporate Pawpaw into your food forest.

Ecological Functions:

It is a flowering tree that attracts butterflies, pollinators, small mammals, and songbirds, which makes pawpaw a good addition to a butterfly, pollinator, or rain garden.

Forage and habitat for Wildlife:

The fruits common pawpaw are eaten by many mammals including opossums, raccoons, foxes, squirrels, and even black bears. White-tailed deer will browse on this small tree and beavers will eat the bark.

Pawpaws (Asimina spp.) are host plants for the caterpillar (larvae) of the zebra swallowtail butterfly (Eurytides marcellus) and the pawpaw sphinx moth (Dolba hyloeus).

The zebra swallowtail (Protographium marcellus, formerly Eurytides marcellus) is a beautiful black and white striped butterfly whose caterpillars feed exclusively on Asimina leaves. (The damage made to the leaves is reported to be negligible in pawpaw orchards [Pomper and Layne 2008]). Some compounds present in the pawpaw leaves (acetogenins, specific substances only found in species of the Annonaceae) are repellent to most insects and birds so the caterpillar accumulates them to avoid predation. These natural bioactive compounds present in the leaves, bark, and twigs of pawpaw and other species of the Annonaceae have shown some insecticidal and anti-tumoral properties (McLaughlin 2008). Of the seven swallowtail tribes, the Graphinii (to which the zebra swallowtail belongs) is one of the largest with about 150 species restricted to the tropics and subtropics except for two, Iphiclides podalirius and Protographium marcellus (the zebra swallowtail), that live in Palearctic and Nearctic regions, respectively (Haribal and Feeny 1998). The fact that both the zebra swallowtail and the pawpaw are the only members of their respective groups to live in temperate North America indicates that both species have coevolved and provides a neat system to study coevolution and adaptation to cooler climates.

Guild Profile/ Potential in Landscape Design Ideas and Themes:

From stunning fruit-tree lined driveways to front yard specimens to edible woodland gardens, the pawpaw highlights landscapes with dense tropical foliage, attractive growth form, and low-hanging fruit. A few ideas for adding pawpaws to the landscape follow.

Pawpaw trees work well with:

City lots (resilient tree)

Townhome yards (close spacing)

Suburban lawns (island and foundation plantings)

Under power lines (limited height)

Businesses and urban areas (specimen trees)

Adjacent to drainage ditches (self-watering)

Rain gardens (stacking functions)

Along driveways and parking areas (using microclimates)

Edible woodland gardens6 (shade tolerant)

In swales (contour planting)

Design Features:

Flowering Tree

Shade Tree

Small Tree

Understory Tree

(picture above shows an extreme close up of a paw paw leaf in our garden as the fall colors begin)

Attracts:

Butterflies

Pollinators

Small Mammals

Songbirds

Resistance To Challenges:

Black Walnut

Deer

Rabbits

Fire

Heavy Shade

Compatibility with garden design types:

Butterfly Garden

Regenerative Garden

Edible Garden

Native Garden

Pollinator Garden

Rain Garden

Since adult Zebra Swallowtail butterflies also feed on flower nectar from milkweed, blueberries, blackberries, lilacs, redbuds, verbenas, and dogbane, consider adding these near pawpaws.

Practical Uses:

Pesticide: White waxy compound highly concentrated in the bark, twigs, fruit, seeds has insecticidal properties and has been used to poison pests. .

Fibre: The thin fibrous inner bark has been used in making strong ropes, strings and fish nets

Dye: A yellow dye is made from the ripe flesh of the ripened fruit.

Ornamental: Pawpaw can be planted as an ornamental, particularly where clusters of small trees are desired.

Border: it can be planted as a shrub border or woodland margin, and is effective around damp areas and along ponds or streams.

Seed Propagation:

Collecting and Storing Seed:

The golden rule to growing a pawpaw tree from seed is to never let the seed dry out. So, when you have just finished the delightful experience of eating a pawpaw and you have decided to grow your own tree, place those seeds directly in the ground where you want to grow your tree. Not ready to grow your tree right away? You can put your seeds in a resealable plastic bag in the refrigerator. Leaving your seeds in room-temperature conditions will cause them to dry out, killing the tiny embryo and prohibiting germination.

Be sure to clean all the flesh off the seeds before storing. If the seeds are coming from rotted fruit, give them a five-minute soak in a diluted solution of bleach: a 1:10 ratio of bleach to water is recommended. The seeds need a minimum of 70 to 100 days of chilling at temperatures slightly above freezing. This is known as “stratifying” the seed—a fancy word that means you are mimicking what happens naturally to temperate zone seeds when overwintering outside. Seeds not directly planted in the ground are typically chilled in the refrigerator between 32° and 40°F (or 0° to 4°C). Storing them longer than 100 days is fine since seeds collected during harvest season—late August through early October—often do not germinate until the following spring. For many of us, that could mean up to seven months in the refrigerator. Just keep an eye out that they do not begin to get moldy from being too damp.

Adding a damp medium, such as sand, to the bag can help maintain the needed moisture; however, if you have enough seeds in the bag, they need no extra medium. Be sure to poke a few needle-sized holes in the bag to vent excess moisture. I keep an eye on my seeds and simply rinse them if there is any fungal buildup.

Germinating Seeds

Pawpaws are slow to start but easy to grow. The saying with pawpaws is that the first year they sleep, the second year they creep, and the third year they leap! With pawpaw trees, it’s all about getting the roots well established. The motto to remember is “roots to shoots.” Pawpaws seeds have high germination rates (over 90%) when a couple of key elements and a single virtue are considered. The elements are temperature and moisture. The virtue is patience.

If you direct seed in the autumn by taking the seed from a freshly eaten pawpaw and planting it where you’d like it to grow—known as “direct seeding”—germination will begin the following summer. The seeds will cold stratify naturally over the winter in the ground and then slowly begin to germinate as the soils warm again, usually revealing a growing shoot in July or August.

While direct seeding is a long affair that requires care to assure good and consistent moisture, it has the benefit of avoiding transplanting, which pawpaws certainly appreciate. For direct seeding, prepare your planting site by creating a well-draining topsoil two to four inches deep. Sow your seeds flat with approximately one inch of soil above the seed. Mulch well with straw or other mulch material to ensure good moisture retention and protect against extended hard freezes. Ideally, at this time you would mulch an extensive area to start the soil conditioning for the tree’s future growth. Placing a piece of chicken wire or hardware cloth over the soil before mulching will help block curious rodents; just be sure to remove the protective covering before sprouting takes place the following summer.

Young seedlings sown or planted in direct sunlight prefer shade for the first year or two, so create a shade structure or put in place a short (18") tree tube.

Seed germinating time can be sped up by starting seeds inside your home or any heated space. After you have stratified seeds in the refrigerator, place the seeds directly in deep pots using a moist potting mix that has been warmed to room temperature (75° to 85°F or 24° to 29°C) in your home or greenhouse.

Insert the seeds, flat side down, with one inch of soil covering the seed. Maintain consistent moisture in the pots. I help maintain moisture in my pots during early-stage germination by mini-mulching with woodchips or sand on the surface. I also keep them in the dark (pawpaw seeds do not need light to begin the germination process)—this allows slow moisture evaporation and does not use up precious light space in the house. At room temperature, initial root emergence is approximately one month; after that, it takes approximately six to eight weeks for the first shoots to begin emerging. When the shoot emerges, it is hypogeal, meaning the seed leaves (cotyledons) remain below the soil surface and the first leaves of the emerging shoot are true leaves. At this stage, be sure the plants have indirect light and warmth. While it is best to keep the pots inside (giving the plants a consistently warm temperature, thus increasing growth rates), if it is past the freezing date outdoors, plants can be moved outside to the shade of a deciduous tree or beneath a shade cloth in full sun. If you use shade cloth in full sun, 30-50% shade cloth is recommended. Remember the mantra with starting pawpaws: patience, patience, patience —and consistent moisture.

To gain a couple of weeks in the germination game, you can use a small heating mat that controls the temperature of the soil medium and causes the seeds to germinate the root tip in just 14 days.

Using just a single heating mat to heat the soil, a pair of dollar store turkey basting pans, and a lightweight seeding mix, seeds will begin germination in just 14 days.

That method can be used to germinate hundreds of seeds at a time for an entire nursery or orchard; or the same method works well for even just a handful of seeds.

Be sure your mat has an adjustable thermostat and set it at 85˚F. Place an empty disposable pan on the mat, moisten the seedling mix, and layer it one inch thick in the pan. Place pawpaw seeds flat, side by side, and cover the seeds with an additional one inch of moistened potting mix. Repeat up to three layers if you have enough seed. Regardless of having one or three layers, make sure the seeds have an inch of seedling mix below and above them; think of it as pawpaw-seed lasagna! Cover your lasagna with an upside-down pan as the lid, and clamp together the two pans. Check every couple of days to be sure the potting medium stays moist. Seed coats will split in approximately 14 days; you will see the white root tip showing. Pick them out as soon as the root pokes out, then pot them with the root radical facing down in deep pots or directly in the ground where they will be grown. Note that placing a piece of insulation, such as folded cardboard, under the heating mat helps keep the heat from sinking into the surface below.

Beware that curious squirrels and chipmunks like to root into pots in search of food and to bury their nuts; this can destroy your young pawpaw seedlings.

In the past, I have lost upwards of half of my seeds to such diggings; now I grow them in critter-proof air root pruning beds and/or A-frame structures covered in chicken wire. This method also conveniently supports the use of a shade cloth. An unused chicken coop or chicken tractor can be easily retrofitted into a pawpaw nursery.

For more information on the air pruning beds I mentioned above:

Guerilla Paw Paw Planting

Pawpaws readily grow from seed, as proven by the many pawpaw seedlings we have popping up all over our property—a result of squirrel and raccoon feastings. While squirrels and raccoons are the ultimate guerilla planters, we humans can also guerilla plant pawpaws in vacant areas. Consider making pawpaw seed bombs by encasing the seeds in balls of absorbent material, such as clay and compost, and tossing them into neglected areas such as urban waste lands, park edges, or your neighbor’s yard. Or even easier: just throw a whole pawpaw fruit into those areas!

(source.)

Cultivation details:

Pawpaw is a forest understory tree. Prefers a rich loamy soil with plenty of moisture and a sunny position. Full sun to part shade. Pawpaw is shade tolerant and would prefer some afternoon shade from other trees or perhaps the shade of a building. Spreads by root suckers to form colonies, so give it room to spread (nfs.unl.edu).

Siting Requirements for Pawpaw Trees:

Full Shade to Full Sun

Pawpaws are commonly known as an understory plant found in the shade of larger trees of the forest. Despite that, shade is not necessary and, in fact, inhibits fruiting. In the heavy shade of the forest understory, pawpaws usually grow a lanky 6 to 30 feet, depending on soil, and often spread out to form patches arising from just one suckering mother plant. Understory trees produce very few fruit because of low light and the absence of another genetically different pawpaw with which to cross-pollinate. Pawpaw trees growing at the forest edge receive more light, reaching heights of about 15 to 30 feet and produce some, yet still limited, fruit. Pawpaws grown in full sun with adequate moisture, drainage, and protection from strong winds, grow into beautiful specimens with a pyramid shape up to 25-feet 2 tall and fruit heavily—with some cultivars bearing over 50 pounds of fruit per tree!

Temperatures:

Tough established pawpaw trees can withstand temperatures as low as -30˚F while dormant, they need warm to hot summers with at least 160 frost-free days to produce ripened fruit. In the United States, pawpaws grow in USDA zones 4 through 9, with most successful fruiting occurring between zones 5b through 9a . In the colder reaches of zone 4, fruiting is currently experimental: the trees can grow well, but may not produce fruit. In mild winter areas with less than 400 chill hours, the trees also can grow well but may not fruit. And in the tropics, they cannot be grown at all. Warmth is needed to ripen pawpaw fruit; there is no way around this reality. The tree will grow well beyond the climatic zones where it will successfully produce fruit, meaning you can have a lovely pawpaw tree in cooler climes, yet there will be no fruit to harvest. This plays out not only in extreme cold zones, but also in mild climates that do not have sufficient warmth to mature fruit, like merry ol’ England and in regions with cool maritime summers.

Wind is not a friend to the pawpaw tree. Wind affects moisture, as strong winds will wick the moisture out of the pawpaw’s large leaf surface, causing the leaves to shred. Strong winds can adversely affect pawpaw flower pollination. Very strong winds can cause extensive damage to the tree’s branches. Exposed windy sites are not good for planting pawpaws.

Moisture the big leaf of the pawpaw signals that it is adapted to humid environments; it needs a minimum of 32" annual rainfall or access to consistent moisture, such as a stream or irrigation. The pawpaw’s deep tap root helps to maintain moisture needs once established in drier soils. Care and development of the pawpaw root is key in successfully establishing its drought resistance and productivity. Pawpaws can grow in upland areas and on slopes with good rainfall, wind protection, and mulching. Drainage Pawpaws need good drainage, as they do not fare well in water-logged soils. that said, pawpaws will grow in a heavy clay soil as long as it drains well. Pawpaw roots will easily begin to rot in persistently wet soils. These trees can grow along waterways where there is access to water, as long as there is good drainage; they often are seen on banks of streams and rivers, but not in waterlogged areas of a floodplain. The other extreme—sandy, dry soils—are not well-suited for pawpaws without supplemental irrigation and heavy mulching. Soil Soil should be neutral to slightly acidic, deep, draining, and, ideally, fertile. Pawpaws can tolerate a soil pH of 4.5 to 7.5, with a sweet spot between 6.0 and 6.5. Pawpaws have a deep tap root that likes a soil it can anchor into; for this reason, shallow, rocky soils are not ideal. They also like good drainage, so planting in boggy soils is not recommended.

Aside from soggy soil and dry windy sites, don’t be surprised about the resiliency of these trees and where they can grow —remember, this is a highly adaptive species! Ideally, a soil test should be completed prior to planting a pawpaw tree to check for pH range and any missing essential elements.

Planting Timing:

The ideal planting time for pawpaws occurs twice a year: in mid-spring, following any chance of freezing temperatures, and early- to mid-autumn, when the ground is still warm and air temperatures remain mild.

Sunlight:

Young pawpaw trees, especially seedlings, that are planted in full sun will need a shade structure for the first year or two 2 because top growth on pawpaw trees is slow for the first couple of years as the plant puts its energy into developing a strong, deep taproot. At year three, or when the tree has grown to 18" or taller, no shading is needed. Once the young trees are established in full sun and good site conditions, the root systems will pump water and nutrients upward to support top growth of about a foot or more each year.

Mulching and the benefits of Fungi rich soil:

Creating a fungal-rich environment for your pawpaw trees above and below ground will help them thrive. Most of our fruit trees evolved in woodland settings rich in organic matter and fungi. Fungi break down organic matter into bioavailable nutrients for plants. This can be achieved by simply adding deep layers of organic material (woodchips, straw, mulch) in a 5- to 10-foot diameter around each tree.

The fungal-rich environment that is created by deeply layering organic matter supports the soil food web, while helping maintain the high moisture levels where pawpaw trees thrive. Plus, this environment also cushions the falling fruit. Be generous with your mulching, as it will quickly break down. Try to consistently maintain four or more inches of mulch, as this will dramatically reduce your long term inputs and maximize tree health and productivity. Adding a mycorrhizal inoculant to the root zone also assures strong fungal networks that boost tree health and resilience.

Companion planting and long term soil care:

Getting your companion plants and ground covers established early around pawpaw trees can reduce your maintenance dramatically and provide ongoing services, such as moisture retention, weed block, soil building, nutrient cycling, and a beneficial habitat for insect ecology. Setting it up right, along with the natural cycles, will maintain and improve bio-functions.

In permaculture, we work with “guilds,” which are sets of companion plants that form a supportive ecology for fruit and nut trees. Guild-building is flexible and largely dependent on your plant interests and uses, as long as certain benefits or “services” are being passed along. For example, having nitrogen-fixing plants (such as lupins) in the guild is important for ongoing feeding needs; mulching plants and ground covers help hold moisture, reduce weeds, and add nutrient-rich organic material; while flowering plants draw in pollinators and beneficial insects.

Ideally, you would add companion plants into an existing compost or mulch the whole area around the tree once all your plantings are in place. With good companion plant establishment, the ongoing need for mulch will be taken care of by the plants themselves; however, mulching at the beginning is helpful in getting all plantings to thrive.

Nitrogen-fixers are often plants in the pea family (legumes) that have a wide range of useful and ornamental choices to match your needs and aesthetics.

On the low-key side of soft perennials—those that die back to the ground each year—are blue false indigo (Baptisia australis) and lupins (Lupinus); they are attractive and low maintenance. For more vigorous nitrogen-fixers, I like woody perennials such as lead plant (Amorpha canescens), bundle flower- (Desmanthus illinoensis), and black locust (Robinia pseudoacacia), the latter of which can also double as an early shade tree for sapling pawpaw trees. With larger woody nitrogen-fixing plants, you will need to cut them back once your pawpaw trees do not need shading. Be ready and willing to manage this key role or your “nurse” will hog the space. When a nitrogen-fixer is cut back during the growing season, its benefits are twofold, as it both drops mulch and releases nitrogen nodules into the root zone. Setting up nitrogen-fixing plants with young trees is a key move to strong establishment and low maintenance. Mulch plants also aid in successful tree establishment and low maintenance by shading and feeding the topsoil with their nutrient-rich leaves and stems, while keeping back weeds and diversifying insect habitat.

“Chop and drop” is a popular saying and practice in permaculture that refers to cutting back the top vegetative growth of vigorously growing plants and allowing the material to fall as mulch. It is simply mulch that is planted in place. Once established, mulch plants can replace the need to bring in straw and wood chips, as these plants create a living mulch to provide the services of weed control, moisture retention, and organic matter for the soil. Some plants, such as comfrey and horseradish, will drop their overgrowth naturally on their own; chopping them two or three times a season can quicken the soil-building process and help stimulate multiple flowerings to benefit pollinators. Nettles are another good mulch plant; though if you are worried about the sting be sure to sow them in their own area, unless you do not mind getting zapped while picking pawpaws!*

*Cut comfrey and nettle make a great liquid fertilizer high in nutrients and minerals. Simply fill a five-gallon bucket with cut plant material and water, let sit for three days, and use as a soil drench.

My favorite mulch plant, by far, is comfrey. Comfrey is a beautiful, soft perennial with luxurious, large, and abundant deep green leaves. It has copious flowers and a willingness to grow in both full shade and full sun. Comfrey is a very easy-to-grow plant that asks very little, yet gives so much. Comfrey is known as a “dynamic accumulator,” meaning its deep tap root pulls up minerals and nutrients from the subsoil into its leaves; when the plant is cut back or dies down, it mulches and releases these nutrients all around your trees. Comfrey shoots out of the ground very early in spring and is one of the first plants to flower and offer nectar to solitary bees. It is a phenomenal medicinal plant as well!

Some of my other favorite mulch and/or companion plants that have multiple benefits are rhubarb, Black cohosh (Actaea racemose), Blue Cohosh (Caulophyllum thalictroides), Asarum canadense (Canadian wild ginger), horseradish, yarrow, and lemon balm. Ultimately, choose mulch plants that you will harvest and utilize, offering the greatest ecological services for those “helpers” you love most: bees, earthworms, spiders, etc.

Pawpaws in Agroforestry

For those with space and market interest in growing pawpaws, agroforestry models are the way to go. Agroforestry incorporates woody perennials (trees, shrubs, etc.) with field crops and/or animals. With agroforestry, you get to stack enterprises for diverse harvests and ecological benefits. Pawpaws stack well into an agroforestry model—especially with animals— since the trees are not palatable to grazing animals . . . even goats! Chris Chmiel, a “pawpaw elder” and permaculture practitioner, combines anextensive pawpaw orchard in Athens, Ohio, with his flock of goats. The chemical Annonaceous acetogenins found in the pawpaws leaves, twigs, and bark make them a rare candidate for browsers. Chris notes that the goats help keep the pawpaw understory free of competing growth and donate natural fertility that also helps draw in the pawpaw’s main pollinator, the glorious fly.

Chris and his wife, Michelle Gorman, operate Integration Acres, which offers commercially available pawpaw pulp, vinaigrette, chutneys, and goat milk cheeses. Integration Acres also incorporates other non-timber forest products, including cultivated mushrooms, ginseng, goldenseal, and spicebush, with pawpaws in adjacent areas not frequented by goats.

Chris also works with improving native pawpaw stands surrounding their homestead by clearing around productive trees that yield chop and drop mulch, mushroom wood, and select wild varieties. Chris points out that working with existing stands can jumpstart production and sales, whereas a pawpaw orchard can take six plus years to begin harvesting.

Another fine agroforestry model that incorporates the pawpaw is exemplified by Red Fern Farm in southeastern Iowa. Tom Wahl and Kathy Dice have successfully mixed the pawpaw into a diverse you-pick agroforestry system that interplants chestnuts, hazelnuts, persimmons, cornelian cherries (fruiting dogwood), heartnuts, and aronia (black chokeberry).

Hügelkultur Beds

Hügelkultur is an old Germanic word basically meaning wood covered with soil and mound culture. It is what happens naturally in an old forest where trees have fallen and decades of leaves have covered the wood, inviting the fungi in to munch it all down into rich compost. These hügelkultur mounds can be created on our landscapes in a variety of scales to build long-term fertility and moisture retention. The moist environment of the soil-covered wood draws in fungi to begin the composting process, which ultimately releases nutrients and holds moisture for plantings. Typically, hügelkultur beds are planted with cane fruits (such as raspberries) or fruiting shrubs that can handle the shifting that takes place over the years of breakdown. When a hügelkultur bed is built and the soil is dumped over top of the wood, a certain amount of the soil naturally cascades down to the base, which makes a nice deep, loose planting soil. This is a happy place for pawpaws, as they gain the benefits of the hügelkultur water harvest and eventual nutrient release.

For more detailed information on creating hugelkultur beds, see Michael Judd’s other book, Edible Landscaping with a Permaculture Twist, which devotes an entire chapter to the subject.

Ground covers are great service providers, as they prevent erosion, weeds, and moisture loss while promoting diversity. These spreaders can do a lot of workfor you by colonizing open ground that otherwise would need to be managedfor weeds. The process of ground cover plants growing and dying back eachseason “pulses” soil growth by adding organic matter above and below thesurface, while creating food and shelter for soil biota. You can speed up thenatural pulsing process by chopping and dropping the plants just after flowering. Many ground covers, such as mints and comfrey, also double as important pollinators for bees and other beneficial insects.

Pawpaw trees are heavy feeders of nitrogen, potassium, iron, zinc, magnesium, sulfur, and calcium. They also need evenly moist soil. The following is my way to approach fertility and water needs.

Thick mulch acts like a sponge for rain falling on it and for any runoff it catches. I find 6 to 8 inches of wood chips in an 8- to 10-foot diameter around each tree holds sufficient moisture in climates receiving 30 or more inches of rain per year. If pawpaw trees are grouped together, the entire area can be heavily mulched to magnify moisture retention. Setting up an island like this offers a good opportunity for adding in companion plantings and other small fruits such as black currant bushes. The ultimate water harvesting comes from creating earthworks that passively harvest rainwater into the ground uphill from your plantings.

For feeding established trees, I apply a generous five- to six-inch layer of aged, but not leached, manure on top of my wood chips around the entire root zone. For my pawpaw trees surrounded by ground covers, I reduce my manure application to a max of four inches to avoid smothering them, and only apply while they are dormant. (Note that nutrient-rich compost can be used in lieu of manure; however, many pawpaw growers choose to use both.)

Following the manure and/or compost application, I then generously spread wood ash to help add potassium (which pawpaws use heavily), rock dust as a remineralizer, and bits of burned charcoal. The charcoal (or biochar) acts as small receptacles for nutrients and beneficial soil critters. You can make your own charcoal, which is popularly called bio-char, or go around collecting from fireplaces and fire pits. Ideally, inoculate the charcoal so it can soak up nutrients before being added as a fertilizer by letting it sit in your compost or manure pile for a few months before adding it as a fertilizer. Charcoal can go a long way toward preventing your nutrients from leaching out quickly. Thick mulch under the manure also helps absorb and hold nutrients longer, and then covering your manure or compost protects the nutrients from volatizing.

For soils low in potassium and calcium I will apply a kelp meal to the soil and a liquid seaweed fertilizer spray to the trees for a quick boost, then add in greensand or granite dust to help for ongoing slow release of potassium, then ultimately plant more comfrey to cycle the potassium needs naturally. If adding additional fertility supplements, I typically do so when laying down manure.

Pollination:

The pawpaw flower is considered “perfect,” 4 as it has both male and female parts. The flowers, typically, are self-infertile because the female pistils and the male stamens ripen at different times in the same flower. The stigmas (the female part of the pistil) mature first, then wither; after that, the anthers (the pollen-producing part of the stamens) shed their pollen. Thus, an individual flower is incapable of pollinating itself. Although the tree is capable of self-pollinating, this very rarely leads to fruit set. In practice, the safest bet is to have at least two genetically different trees in close proximity to each other because this is known to increase cross-pollination, and thus, fruit set.

Two different cultivars, any two seedlings, or a combo of a seedling and a cultivar, will cross-pollinate with one another. Cultivars are seedlings that have been evaluated, tested, selected, and then named. They are propagated through grafting. Seedlings are trees grown from seed and are not named cultivars.

Blooming takes place over a two- to three-week period, where each flower begins life in the female stage receptive to pollen; after a few days, the stigmas dry up and the flower morphs into the male stage, where the anthers release pollen—a truly bi-sexual species! The long bloom time allows for flowers to overlap, creating and receiving pollen. There seems to be no great variation in bloom timing among cultivars, so all should overlap in pollination for a week or more.

Pawpaw flowers are pollinated by ants, flies, beetles, fungus gnats, and humans. Humans have been very successful pollinators when conditions do not favor insect pollination.

If pollinators are not active due to cold temperatures, windy sites, insecticide and fungicide use, or lack of ecological diversity when the flowers are open, then hand-pollinating with a paint brush can be easily and successfully achieved.

Using a small, soft artist’s paint brush, collect the male pollen grains, which appear as small, yellowish-colored particles on the anthers, and daub them on neighboring tree flowers with receptive female parts or stigmas. The stigmas appear as sticky, green and glossy tips of the pistils. Hand-pollinating typically has a very high success rate, so daub away!

Do not use insecticides if you want healthy natural pollination to occur. Do put your compost pile in the vicinity of your trees, as it really can increase insect pollinator activity.

The tree commences bearing in 4 - 6 years from seed and yields up to 30 kilos per tree.

Harvesting:

The ideal is to hand-pick pawpaw fruit. Hand-picking pawpaws is part science and part art—one that involves a fair amount of fondling. Pawpaw fruit remains dead hard and green until it is almost ripe, and then it ripens very quickly. Depending upon the cultivar, pawpaw fruits may or may not change color to signal they are ripe; those that do will change color when ripening, moving from a solid green to light green to yellowish. This is commonly called color break.

The key is to observe and feel the fruit daily as the ripening season begins by gently squeezing the fruit—as you would a peach —to test for softening. When the pawpaw is just beginning to ripen, the yield from finger pressure will be subtle, but enough so you can sense it is not rock hard anymore. If it has been ripening on the tree for a few days, it will be obviously soft to the light squeeze. This is where being gentle with your testing is key, as the fruit will bruise very easily once ripe. Any bruised areas of the fruit will ripen and rot quickly, usually within 24 hours.

If you’re not eating your freshly harvested pawpaw fruit right away, be sure to handle it carefully, as any impact will bruise the flesh. Do not pile pawpaws on top of each other; rather, place them in a single layer in your harvest bin or box, as even their own weight will cause damage—that is how easily a ripe pawpaw can bruise!

Spreading a thick layer of fresh straw under your pawpaw trees just before harvest season helps cushion fruit that falls in between hand-picking sessions.

Note that fruit already fallen to the ground are usually quite ripe and will have a very short shelf life. Eat or process these fallen fruits right away.

Fruits can be picked when the earliest signs of ripening are detected and then left to ripen at room temperature (a quick process) or refrigerated (for slower maturation). At room temperature, a pawpaw that is just starting to ripen will mature to perfection in 24 to 36 hours. A fragrant, fruity aroma will be detected; the flesh will be firm and evenly textured; and the light, sweet notes of flavor will reward your senses in delightful ways. At 48 hours at room temperature, the fruit texture will be considerably soft and more custard-like; the flavor and aroma notes will be rich and deep. At 72 hours of ripening at room temperature, the fruit skin and flesh become discolored and very soft, and flavors tend toward rich, bitter notes of caramel and coffee.

If fruit is picked before the ripening process has begun, it will stay hard and not ripen. If you try eating an under-ripe pawpaw, you will likely end up with a serious tummy ache!

Storing and Processing

Ripening pawpaws pump out large quantities of ethylene gas, a plant hormone that stimulates ripening metabolism, which means ripe pawpaws do not store fresh for very long. Under ideal conditions, when pawpaws are hand-picked just prior to being fully ripened, and not bruised in transit, they can be kept in refrigeration (34°F) for up to three weeks, but typically a ripe pawpaw fruit will only last one week in refrigeration. While pawpaws are not like apples that can be stored for a long time, the good news is that pulped pawpaw fruit freezes well.

First, freeze the fruit whole (skin and all). Granted, you will need enough freezer space to hold the whole fruit. (Note: if you have too many fruit to put in the freezer at one time, you can hold some in the refrigerator up to a few days following harvest until you’ve processed the first batch.) Once frozen solid (this takes no more than 12 hours), remove them from the freezer, then wait 20 to 30 minutes. Peel the skin with a peeler, like you would a potato, then pry the slightly thawed flesh open. The seeds pop out as clean as can be! If you don’t wait the 20 to 30 minutes, the fruit won’t pry open. Once deseeded, pile your chunks of still mostly frozen pulp into resealable plastic freezer bags and pop them back in the freezer, where they can stay for up to two years. Be sure to write the date of freezing on the bag to alleviate the guesswork.

Types/Varieties

While there are many well-known and noted pawpaw cultivars currently in the nursery trade, there are hundreds—if not thousands—more in the wild waiting to be discovered, and unknown possibilities in select seedlings.

There are about 40 named cultivars circulating in the nursery trade. Mostly, these are selections of exceptional wild trees, along with a handful of bred cultivars. Choice wild selections and bred cultivars have superior traits that include large fruit size, balanced flavors, firmer flesh, low seed-to-pulp ratio, consistent and productive fruit bearing, and ornamental value. There are also “select seedling” pawpaws for sale in the nursery trade. These have been grown from seeds collected from cultivated pawpaw orchards that have no cross pollination with wild trees. Generally, select seedlings cost less and are a good deal for the home grower, as they come close to—or even exceed—the quality of their cultivated parents. Due to their genetic diversity, some select seedlings have more potential to adapt to regional conditions.

There are several specific cultivars of the pawpaw tree, each of which offers its own distinct flavor, texture and appearance.

Discovered Pawpaws: Best of the Wild

These cultivars have been discovered in the wild and identified as outstanding specimens or choice selections from avid pawpaw growers.

Overleese

Selected from the yard of Mr. and Mrs. Overleese in Rushville, Indiana, by W.B. Ward in 1950, this cultivar of the pawpaw was selected as the winner of the “Best Fruit” category at the Ohio Pawpaw Festival 2011. The Overleese is the “mother” of many excellent offspring, including the famed “Shenandoah,” . The large-sized fruit is a long-proven favorite for steady productivity, has a low seed-to-pulp ratio, and offers a moderate holding quality. The Overleese is an early- to mid-season producer of large fruits with medium productivity. Its fruit is oval or round in shape, and produces a mild-flavored, creamy yellow-orange pulp. The lighter flavor is appreciated by those not wanting the richer notes produced by some of the other cultivars.

Davis

Discovered in the Michigan woods by Corwin Davis in 1959, this moderate bearer is an attractive tree. In fact, the Davis cultivar is one of the most attractive pawpaw trees in my own personal collection, with a full, handsome growth and deep green leaves. Davis makes for a good edible landscape—an all-star among pawpaws! Some of the excellent traits of the Davis include: the medium-sized fruits yield a light-yellow flesh that gives way to an attractive green fruit when ripened; it keeps well in cold storage; and the pleasant flavor is sweet and mild.

NC-1

NC-1 is a hybrid seedling of Overleese and Davis—also known as “Campbell’s #1”—and was selected in Ontario, Canada, in 1976 by R. Douglas Campbell. This is one of the best cultivars for northern regions or regions with cooler summers, as it is an early bearer; it also grows well throughout the southern range. NC-1 is one of the most ornamental of the pawpaw trees. Its attractive, dark green foliage gives way to round or oval fruit resembling the Overleese, with a low seed-to-pulp ratio and good holding quality. NC-1 produces largesized fruit in low to moderate quantities. It has a firm fruit texture with excellent flavor and buttery yellow pulp.

Mango5

A strong-growing and productive cultivar prized for its light and sweet flavored pulp the Mango pawpaw was discovered from the wild in Georgia by Major C. Collins, circa 1970. The Mango pawpaw fruits are large and round, resembling mangoes, with a soft and creamy texture. The fruits do not store as well as most other named cultivars, quickly turning mushy upon harvest; for this reason, the Mango is a cultivar best suited to fresh eating or immediate pulping. This tree produces large-sized fruits and is preferred by those not into the rich and complex flavors of some pawpaw cultivars.

Sunflower

One of the most popular and recommended cultivars, the Sunflower cultivar is a staple in any collection. This strong-grower was discovered in the Kansas wild by Milo Gibson, circa 1970. Sweet and rich with a golden-yellow pulp and firm texture with few, yet large, seeds, this pawpaw ripens mid- to late-season, so it may not be best suited for extreme northern growers. This amazing cultivar produces large-sized fruit and is self-fertile; given this, it is always best to plant more than one cultivar or seedling to improve fruit set. The Sunflower tested high in the Cornell University trials6 and won best fruit at the Ohio Pawpaw Festival both in 2006 and 2010.

Pennsylvania Golden

Often abbreviated as “PA Golden,” this cultivar is famed for its early and heavy production. It is a top-choice cultivar for the northern reaches, plus regions with shorter growing seasons and cooler summers, yet it grows well in warm areas, too. The seeds were elected by John Gordon of New York from trees that trace back to George A. Zimmerman, a famed pawpaw culturist in the 1920s and 1930s. There are four PA Goldens, known as the “PA Series.” The series is identified as PA Golden #1, #2, #3, and #4, with #1 and #4 being the most common in the nursery industry. They are all early ripening and a must-have for any collection living in a climate with a short growing season. The PA Golden has deep golden pulp with a creamy, somewhat watery, texture and rich flavor. Many consumers prefer this richness, while others find it to be too strong. The softer texture means the fruit does not store well and is best eaten fresh or pulped quickly.

PA Goldens to resemble wild pawpaws in many ways: smaller, seedy, and sometimes with slight bitter undertones. That said, it is a great growing, very hardy, and productive tree whose small-to-medium sized fruit turn yellow when ripe, making harvest time obvious.

Sue

Discovered by Don Munich in southern Indiana. The Sue cultivar is known for its sweetness. Jim Davis, owner and operator of Deep Run Pawpaw Orchard in Westminster, Maryland, agrees, as the Sue is sweet and simple, ideal for those who don’t go for the stronger pawpaw flavors. The small- to medium-sized fruit produces a soft, yellow pulp that makes for a sweet creamy dessert. Sue’s thin skin turns yellow when ripe and is a good producer. Multiple records indicate the Sue to be resistant to Phyllosticta asminae, a fungus that often discolors the skin of pawpaw fruit with black spots and blotches.

Ford Amend

The Ford Amend merits mention as a pawpaw selected in the Northwest region of the United States where summers are not extremely hot. Grown successfully since the 1950s and still being sold in the nursery trade, this version yields small- to medium-sized fruit offering a flavorful orange pulp. It matures in late September in Oregon and neighboring states.

Bred Cultivars

The following are the results of meticulous research, thorough and careful genetic cataloging, and extensive trials.

PETERSON PAWPAWS

Neal Peterson is the breeder of seven cultivars, collectively known as “Petersons Pawpaws.” They are named after U.S. rivers with Native American names. The short story is that Neal tracked down the historic pawpaw collections from a century ago when pawpaws were revered and celebrated. Roughly 1,500 seedlings grew out of this collection, which Neal evaluated over a 20-year period. He selected the very best, finally narrowing it down to just seven outstanding cultivars: Shenandoah, Allegheny, Susquehanna, Potomac, Rappahannock, Wabash, and Tallahatchie. Detail on each cultivar follows. Neal’s dedicated work has created cultivars with desirable characteristics in flavor, texture, size, seed-to-pulp ratio, and productivity. When you grow a Peterson Pawpaw, you know what to look forward to. Neal is currently working on spreading his cultivars around the world.

Shenandoah

The “Queen” of Peterson’s Pawpaws, the Shenandoah has a long list of fine attributes. It is a very steady producer of large fruits with few seeds and a spaced-out ripening period that can stretch over a month’s time in mid-season.

Shenandoah often bears a single fruit rather than a cluster, which makes picking fruit much easier and reduces potential fungal build-up that can occur between clustered fruits, which have a fragrant, sweet flavor, a custardy texture, and a smooth aftertaste. Shenandoah is a good first pawpaw fruit to try, as it is on the light, sweet side of the pawpaw-flavor spectrum. It is a long-proven producer at Jim Davis’s Deep Run Pawpaw Orchard. (6% seed by weight)

Allegheny

The Allegheny is a personal favorite of mine for its strong growth, abundant fruiting, and balanced flavors. Neal almost did not release this one due to its smaller fruit size and higher seed-to-fruit ratio; however, he relented to popular pressure, thank heavens! The Allegheny produces fruits that have a medium smooth texture with yellow pulp that is sweet and rich, providing a hint of citrus. This is a very precocious and productive cultivar that needs to be well managed; the fruit should be thinned out as it has a tendency to overbear, which on any fruit tree can lead to overall decline in tree vigor and fruit quality. The tree is a mid-season producer of medium-sized fruit that grows in clusters—two or three per bunch with a limited number of clusters per branch.

Thirty-five pounds per tree (for any pawpaw) is a good goal in order to keep tree health in balance. The Allegheny is another steady producer in Jim Davis’s Deep Run Pawpaw Orchard. (8% seed by weight)

Susquehanna