Why Involuntary Governance Structures are Not Compatible with The Permaculture Ethical Compass

This post explores Voluntaryism, Brehons, "The Indigenous Critique", what Charles Eisenstein describes as "The Concrete World" and offers sign posts to instead choose a different future

This post is going to be an exploration of the nature of involuntary governance structures (Statism) and an exploration of cultures and peoples that existed without a centralized state system.

I will also be looking at the above described systems through the lens of the permaculture design ethics and explaining why those statist systems are inherently incompatible with the ethics of permaculture design.

We will also examine the role of money and how it shapes our psychology, our motivations and our society (as seen through the lens of the peoples who lived here on Turtle Island and were seeing the ways of the European interlopers arriving on their shores through eyes that had seen a different way of living than we experience today).

Firstly, What is involuntary governance?

Any form of government that is imposed upon individuals using violent coercion without the consent of that individual (this applies whether one would describe that governance system as a “Fascist”, “Communist”, Feudal Dictatorship or “Democracy”).

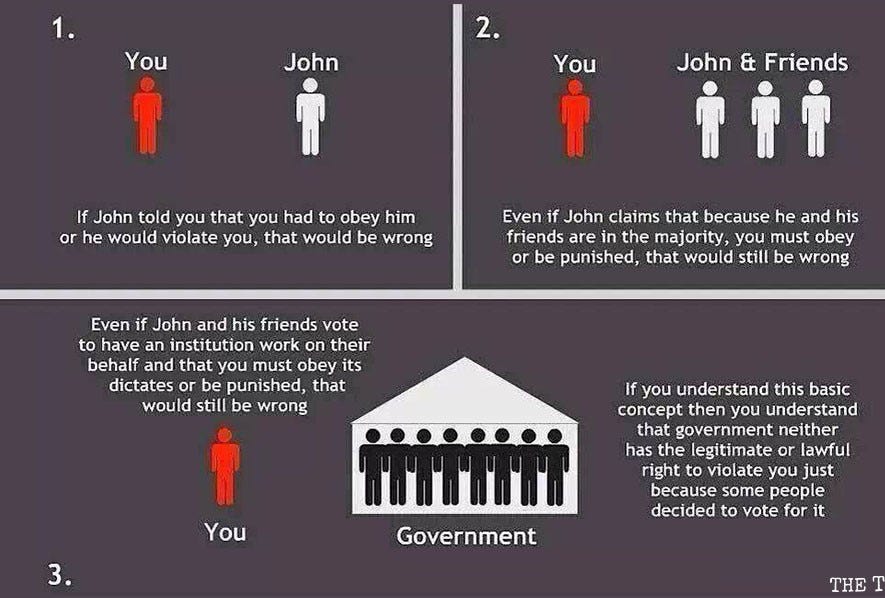

In it’s idealistic format, Democracy involves using the threat of violence (via armed agents of state which will come and harass, kidnap and potentially kill you if you resist) to coerce the minority into capitulating to the will of the majority.

That system (though it is rarely experienced by those living within nations that label themselves as such due to voting fraud, corporate lobbying, blackmail, and the hyper-consolidation of wealth allowing plutocrats to buy politicians) even if it functioned as advertised, would be inherently immoral.

Threatening other people to behave as you want them to and give you their money (because you and your friends think they should) is ethically wrong. That ethical principle does not change simply because you attach the word “government” or “democracy” onto the equation.

I offered a section in my book that spoke to a concept called Voluntaryism, however, due to printing budget limitations I was not able to fully elaborate on my thoughts on Involuntary Governance (“Statism”) and how I feel that such systems of governance are incompatible with the permaculture design ethics. I aim to remedy this in the essay below.

The following is an adapted excerpt from pages 293-301 of my recently published book (Recipes For Reciprocity: The Regenerative Way From Seed To Table).

When I look through the Permaculture ethical lens at how much of our modern day society operates and is organized I immediately recognize that we have been conditioned (through multiple-generational programming) to accept many ideas that are degenerative, immoral and that do not align with the ethics of Earth Care-People Care-Future Care.

Involuntary governance structure’s failures listed in the context of the permaculture design ethics:

Earth Care - Whether you feel that it is a minority or people or a majority of people that (whether due to ignorance, apathy or greed) will choose actions that are ecologically degenerative (actions that harm the biospheres/biodiversity of the living Earth) involuntary governance systems are not a viable solution to that ignorance, apathy or greed.

If you feel it is a minority of humanity that (whether due to ignorance, apathy, greed or a combination of those) are inclined to make ecologically degenerative choices, having a government with a monopoly on force only serves to allow those people choosing degenerative actions a platform through which they can dominate all other humans (and non-human beings) via weaponizing institutionalized theft under threat of violence (aka “taxation”) to further and accelerate their degenerative/greed based endeavors. Those who are driven by greed and those who are apathetic to the well being of others (sociopaths) gravitate towards positions of political power (and excel within said government structures).

If you feel that it is a majority of humanity that (whether due to ignorance, apathy, greed or a combination of those) are inclined to make ecologically degenerative choices (though, I personally do not think this is the case) having a government with a monopoly on force which exerts the will of the majority on the minority through the threat of violence only serves to disempower the few who do care about the living Earth and empowers those who wish to pillage her, to do as they please.

Also, not only do involuntary governance structures attract sociopaths and psychopaths into positions of power it is also important to highlight that Statist structures (and the corporatocracy that dominates nation-states in modern times) also actively exerts pressure on the population and provides incentives which results in the creation of more sociopaths and psychopaths.

In addition to how Statism empowers/encourages ecologically degenerative businesses and behaviors in citizens, it also directly funds and engages in mass ecocide itself, through weaponizing government funded thugs such as the

C-IRG in Canada and how our tax dollars are used to enforce the will of corporate industry at gun point to Clear Cut some of the last ancient/primary temperate rainforest watersheds on Earth.

People Care - Violent coercion of a minority at the behest of a majority (democracy) of a given population is the most ideal form of involuntary governance I have seen presented to me and that system of governance is inherently immoral. Violating the few to please the many is wrong, we may have been conditioned to think it is the best we can do, but as you read further below, you will find that is a fallacy.

As I outlined (with an abundance of supporting evidence) in my article on Anthropocentrism and The Continuity of Colonialism the repeated result of imposing statism onto cultures that existed without a centralized state previously, was that agents of empire and governments were weaponized in order to commit acts of genocide (via methods such as using food as a weapon with the intentional extermination of the Buffalo in order to starve and destabilize indigenous cultures so that their land could be stolen and allocated to the state).

The phenomenon of statism (and expansions of the imperialistic and parasitic way of living that such a system embodies) resulting in the mass murder, oppression of and theft from indigenous peoples is not something that only exists in the past but rather it is a ubiquitous and integral characteristic of statist systems of both the past and present.

Thus, there is no logical way to argue that using violent coercion on a minority could be described as “people care”.

Future Care - As stated in the Earth Care section above, involuntary governance structures invariably result in perpetual ecological devastation, degeneration and the pillaging of the living inheritance of our great grandchildren, therefore such a system embodies the opposite of “future care”.

Additionally, through federal (involuntary) governments borrowing from transnational banking cartels (such as the IMF and BIS) and then passing that “deficit”/debt onto future generations that have yet to be born these are governance structures that essentially sell out the livelihood of our unborn grandchildren by saddling them with debt they had no choice in having added onto their tax burden.

Thus, involuntary governance structures (such as democracy) embody the opposite of future care (trading in the well being of both the inheritance that is health of the living Earth and the financial potential of our grandchildren for short term selfish gains).

We have all been indoctrinated since we were very young to unquestioningly accept the domination of involuntary governance systems (aka multi-generational organized crime syndicates) in our lives and see the "big brother" figure as something that is necessary to 'keep us safe'. However, students of history quickly learn that the facts do not support that story of the role of governments in our lives.

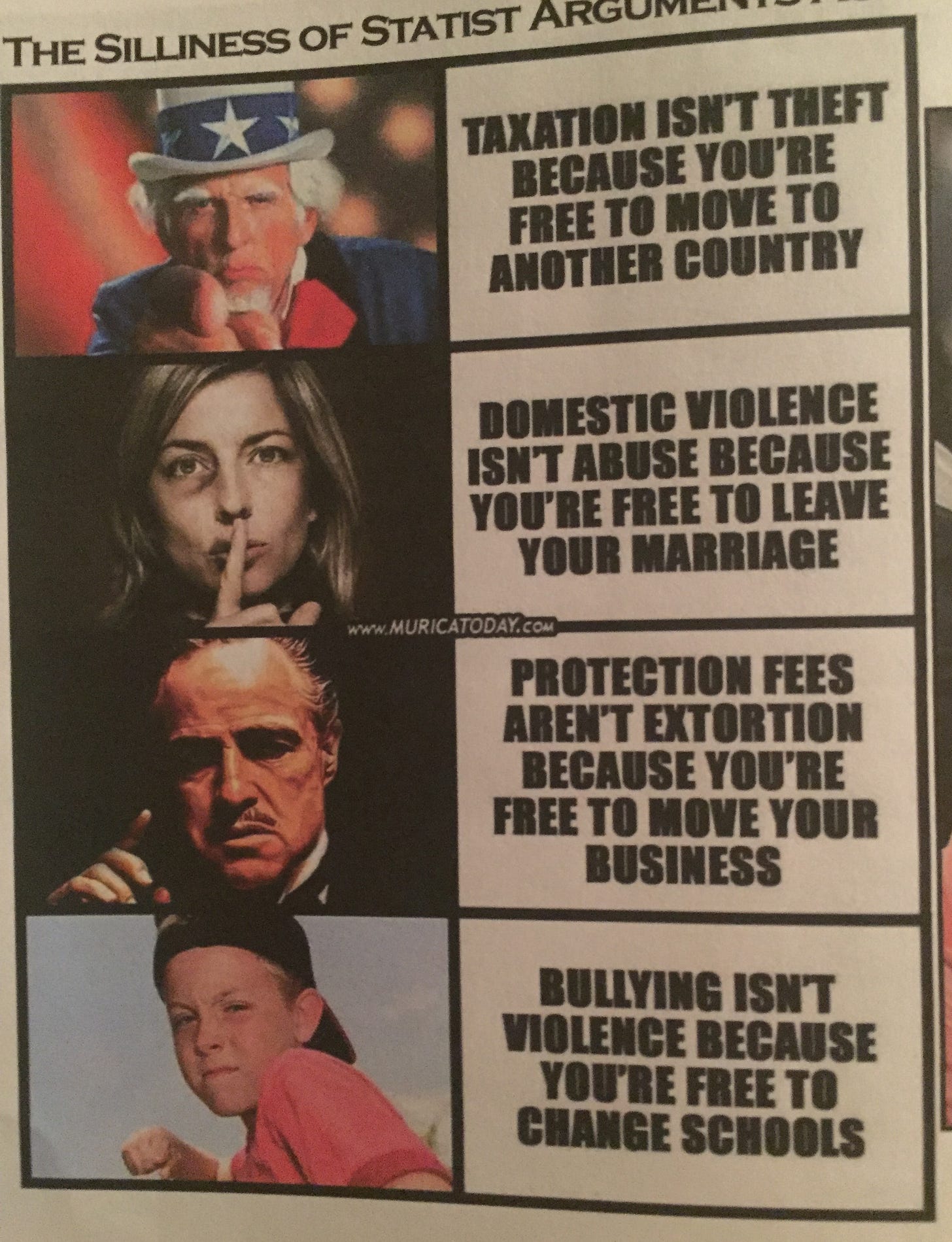

As I explained in my essay on the racketeering operation that is modern warfare: Many in our current society live in a sort of Stockholm Syndrome type relationship with government.

When the Italian Mafia tells you they are going to provide you with “protection services” (and then if you do not pay up they beat you down, take your stuff and maybe make you disappear) that is called “Pizzo”.

When your government does that same thing, it is called “taxation”.

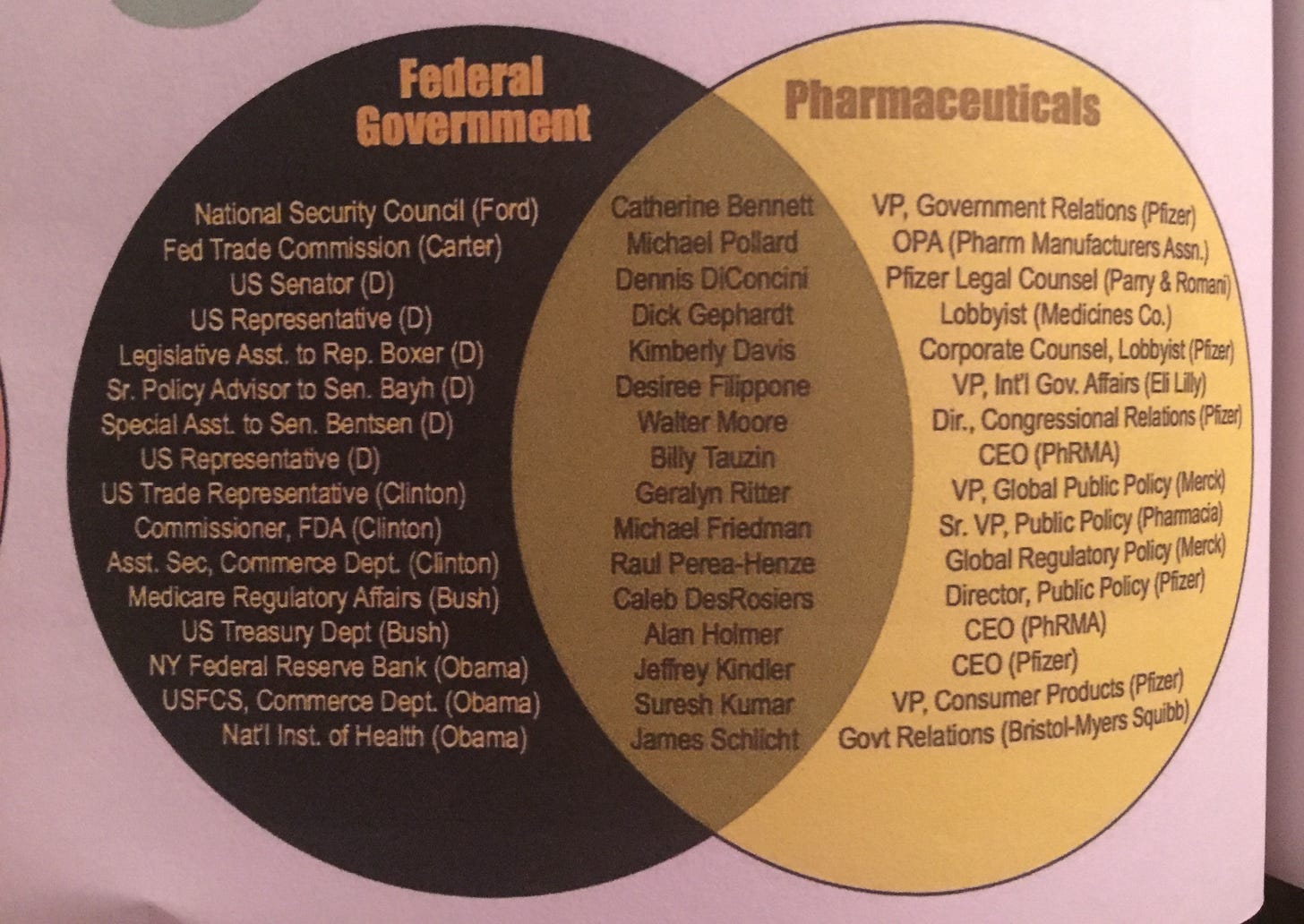

The military industrial (and now also the big pharma/big Ag/big tech industrial) complex uses its influence over nation states to pass laws and influence policy in combination with the multigenerational racketeering operation known as ‘taxation’ in order to take your money from you (under threat of violence and kidnapping) to spend on bullets, guns, bombs, landmines, drones, “vaccines” and other chemical/biological weapons.

When will we collectively learn the lesson that many of the institutions we have been raised to trust and respect are inherently immoral and degenerative?

When will we muster the courage to break the cycle and instead peacefully choose a different path?

"The state is not a benevolent force, despite what the most brainwashed of statists believe. It is not even a neutral tool that can be used for good or ill, as those who consider themselves pragmatists believe.

It is violence. It is force. It is aggression. It is people believing that what is wrong for any individual to do is perfectly OK if an agent of the state does it.

If I steal, it is theft. If the state steals, it is taxation. If I kill, it is murder. If the state kills, it is warfare. If I force someone to work for me involuntarily, it is slavery. If the state does it, it is conscription. If I confine someone against their will, it is kidnapping. If the state does it, it is incarceration. Nothing has changed but the label.

What binds us to the state is the belief that there is a different morality for anything that has been sanctified through the political process. "Oh, 50%+1 of the population voted for forced vaccinations? Then I guess we have to comply." If you scoff at that sentence, how about if the vote were 100%-1? Would that change the morality of resistance? How about if forced vaccinations were mandated by the constitution? Then would you be compelled to submit?

Does the ballot box transform the unethical into the ethical?

Of course not. But I'll tell you what it does do: It makes everyone who casts their ballot a part of the process that legitimizes the murder and violence committed by agents of the state."

- James Corbett (from Government Itself is Immoral)

So, as you can see, we have been indoctrinated into a belief system called Statism which is immoral and degenerative, but what alternatives are there to involuntary governance systems (aka multi-generational organized crime syndicates) ?

Some of the following paragraphs contain material from voluntaryist.com which give some background info on the principles of Voluntaryism.

Voluntaryism is the doctrine that relations among people should be by mutual consent, or not at all. It represents a means, an end, and an insight. Voluntaryism does not argue for the specific form that voluntary arrangements will take; only that force be abandoned so that individuals in society may flourish. As it is the means which determine the end, the goal of an all voluntary society must be sought voluntarily. People cannot be coerced into freedom.

“The state represents violence in a concentrated and organized form. The Individual has a soul, but as the state is a soulless machine, it can never be weaned from violence to which it owes its very existence.” - Gandhi

The Epistemological Argument

Violence is never a means to knowledge. As Isabel Paterson, explained in her book, The God of the Machine, "No edict of law can impart to an individual a faculty denied him by nature. A government order cannot mend a broken leg, but it can command the mutilation of a sound body. It cannot bestow intelligence, but it can forbid the use of intelligence." Or, as Baldy Harper used to put it, "You cannot shoot a truth!" The advocate of any form of invasive violence is in a logically precarious situation. Coercion does not convince, nor is it any kind of argument. William Godwin pointed out that force "is contrary to the nature of the intellect, which cannot but be improved by conviction and persuasion," and "if he who employs coercion against me could mold me to his purposes by argument, no doubt, he would.. He pretends to punish me because his argument is strong; but he really punishes me because he is weak." Violence contains none of the energies that enhance a civilized human society. At best, it is only capable of expanding the material existence of a few individuals, while narrowing the opportunities of most others.

The Moral Argument

The voluntary principle assures us that while we may have the possibility of choosing the worst, we also have the possibility of choosing the best. It provides us the opportunity to make things better, though it doesn't guarantee results. While it dictates that we do not force our idea of "better" on someone else, it protects us from having someone else's idea of "better" imposed on us by force. The use of coercion to compel virtue eliminates its possibility, for to be moral, an act must be uncoerced. If a person is compelled to act in a certain way (or threatened with government sanctions), there is nothing virtuous about his or her behavior. Freedom of choice is a necessary ingredient for the achievement of virtue. Whenever there is a chance for the good life, the risk of a bad one must also be accepted.

The Means-End Argument

Although certain services and goods are necessary to our survival, it is not essential that they be provided by the government. Voluntaryists oppose the State because it uses coercive means. The means are the seeds which bud into flower and come into fruition. It is impossible to plant the seed of coercion and then reap the flower of voluntaryism. The coercionist always proposes to compel people to do some-thing, usually by passing laws or electing politicians to office. These laws and officials depend upon physical violence to enforce their wills. Voluntary means, such as non-violent resistance, for example, violate no one's rights. They only serve to nullify laws and politicians by ignoring them. Voluntaryism does not require of people that they violently overthrow their government, or use the electoral process to change it; merely that they shall cease to support their government, whereupon it will fall of its own dead weight. If one takes care of the means, the end will take care of itself.

The Integrity, Self-Control, and Corruption Argument

It is a fact of human nature that the only person who can think with your brain is you. Neither can a person be compelled to do anything against his or her will, for each person is ultimately responsible for his or her own actions. Governments try to terrorize individuals into submitting to tyranny by grabbing their bodies as hostages and trying to destroy their spirits. This strategy is not successful against the person who harbors the Stoic attitude toward life, and who refuses to allow pain to disturb the equanimity of his or her mind, and the exercise of reason. A government might destroy one's body or property, but it cannot injure one's philosophy of life. - Furthermore, the voluntaryist rejects the use of political power because it can only be exercised by implicitly endorsing or using violence to accomplish one's ends. The power to do good to others is also the power to do them harm. Power to compel people, to control other people's lives, is what political power is all about. It violates all the basic principles of voluntaryism: might does not make right; the end never justifies the means; nor may one person coercively interfere in the life of another. Even the smallest amount of political power is dangerous. First, it reduces the capacity of at least some people to lead their own lives in their own way. Second, and more important from the voluntaryist point of view, is what it does to the person wielding the power: it corrupts that person's character.

Many prophecies have foretold (describing in detail) a time in which the depravity and degeneration that is prevalent in modern society today would lead us to a fork in the road. We now stand at that fork and each of our decisions will decide what path we take.

While there are many prophecies worth examining to understand where we have been, where we are and where we may be headed, I will share one in particular that I feel is pertinent to the subject matter we are discussing here.

The people that called the land where I now live home before the Europeans arrived and removed them speak of a Prophecy Of The Seventh Fire. You can watch a video clip with Robin Wall Kimmerer sharing one interpretation of it here:

In the prophecy her elders spoke of, there would come a time when humans would neglect their sacred connection to the living Earth and we would face a fork in the road. One of the paths is soft and green and the other is charred, jagged and burnt.

The prophecy says that there will come a time when people of all colors and creeds who seek to embark down the green path together must first look back to the teachings and the wisdom of their ancestors, to choose as they did, to nurture a symbiotic relationship with the land and embrace a reverence for the living Earth (which will provide them the guidance they on the path forward).

I believe that in many ways, each of us stands at that fork in the road that the Seventh Fire prophecy describes, right now. I believe that Statism, materialism, reductionist/mechanistic science, machoism, ego, violence, and dependence on technologies/products created by big hyper-consolidated corporations are choices that lead down the well worn and scorched path.

Thus, instead of feeding into the fire of violence, commodification of nature, materialism, hubris and fear that leads one down the black and burnt path, I strive to look to my Celtic ancestors (and I also strive to look to the ancestors of those that called this land where I live now before I was born) for wisdom in how I can live in close connection with the Earth, to be an effective protector of life, embodying truth and working to align my efforts with the regenerative capacity of nature (and with others interested in co-creating a new path forward to build intentional communities). Regardless of the level of depravity any bullies chose to involve themselves with, I choose to walk this path with unconditional love, compassion, reverence for all life and integrity guiding each of my actions.

Each of us are faced with the choice that can lead down one of two roads now. We either step outside our comfort zone to learn from the wisdom of our ancestors that forged a close knit symbiotic relationship with the land, learning skills, gathering knowledge and hands on experience (and do not allow any excuses to get in our way) which will enable us to provide for ourselves and our loved ones without centralized systems, or we choose cowardice, complacency, stagnation and “learned helplessness”.

If we want to guide our lives and designs by the ethical compass of people care-earth care-future care that means we have to live by example and embody truth and moral courage not only in the garden, but as we engage with our fellow humans in the society around us. Stand firm in what you know to be true, peacefully and in clarity. Be the change you want to see, set clear boundaries, do not allow degenerative systems to shape how you live through coercion. Closely observe what is happening around you, see the patterns and where they are headed... and if you do not like the trajectory, choose to embody a different pattern.

We can cultivate and nurture the seeds of moral courage and solidarity in those around us to grow through choosing to replace the 'weeds' and toxicity in our society by planting the seeds of hope, truth and courage (in our actions and interactions in our day to day life) and 'remediating the soil' of our society through aligning our selves with the power of truth, and living it.

I have begun to explore the ancient ways of our ancient Celtic and Druidic ancestors in the hopes I might glean some wisdom from their ways of perceiving the world, perceiving their fellow humans (and non-human beings) and their strategies for cultivating food and organizing communities. I have done this so that I might draw from their deep well of experience as I move forward to contribute towards creating intentional communities and decentralized food/medicine cultivation systems.

Perhaps taking a look at the various ways in which our ancestors made their existence possible can offer us some wisdom on the path ahead?

Perhaps we can look to our ancestors that lived on the British Isles (before the Romans invaded) to find some wisdom to ground us as we work to chart a new path forward and create intentional communities.

Perhaps we can head the suggestion made in the Prophecy Of The Seventh Fire and look to our ancestors to learn something about forging a path towards embracing our own freedom, sovereignty integrity and responsibility as individuals and as a community?

Perhaps we can help those that have been indoctrinated into the religion of Statism to awaken Saoirse (which is the Irish Geilic word for "Freedom") within themselves by looking to find common ground in our recognition of the sacredness of the natural world?

Brehon Law (is seen by some) to have facilitated the foundation for a peaceful and productive (stateless) society which existed for nearly a millennium without police or prisons.

For those that are unfamiliar with the term who are reading this, ‘Saoirse’, is an ancient concept that comes from the original Brehon laws of the pre-colonial Gaelic world before the time of Emperor Constantine’s distorted version of Christianity reached the shores of Eire (aka Ireland).

In those days, the idea of freedom, honoring the non-aggression principle (or facing the consequences directly from your peers) could not be separated from the community or nature, because it was embedded in the medicine, language and culture of the Gaelic tribes and the Druids.

Saoirse means many things to different people. For some it means freedom to think, express and freedom to learn, for others it’s the freedom of imagination and the freedom of the spirit. And for some it also means freedom to set up parallel societies.

The forest and all aspects of the living Earth were seen as sacred and revered by the Druids, and their successors, the Brehon.

Thus, the wrapping of that freedom or “Saoirse” which the ancient Gaelic people’s were taught to embody and respect was rooted in the truth and freedom which was recognized in the natural world, or more specifically in trees. Each tree had a series of philosophies around it in the oral culture ( a voluntarily agreed upon system for protecting nature). This system was agreed upon each time a word was written or carved into stone for it became the foundation for the Ogham Script.

Ogham script is one of the oldest forms of writing and is referenced throughout Celtic mythology. Long before the days of paper, stone was inscribed as a form of communication. Ogham script consists of lines representing twenty letters. These lines can still be seen to this day along the edges of many standing stones found throughout the Celtic nations.

For those that are not aware, Europe’s very first alphabet (Ogham Script) arose in Celtic culture and is comprised of characters that are mostly named after trees (all of which were considered sacred because of their medicinal properties). The alphabet begins with a symbol for a shoreline pine and ends with a blackthorn tree.

The usage of this living language rooted in the trees and medicine plants provided a cultural and literary foundation that ensured people didn’t harvest everything and left medicine for their children’s children’s children. Trees with important medicine had a sacred status as a form of protection against human greed.

Irish botanist, medical biochemist (and keeper of the ancient indigenous Celtic medicine knowledge) Diana Beresford-Kroeger comments on the connection of the natural world to the word and concept of Saoirse by saying:

“A great forest not only heals people with medicinal aerosols but rekindles freedom.

You go into a forest and come out in peace. That is the spiritual reality. You go in one way and come out changed, whether you have dogs and cats with you or people. You go in and it opens up your spirit, and your thinking changes as your breathing changes and you come out and you are refreshed.

You never come out with tension in your heart. You come out feeling liberated. And again, there is that word, saoirse. You feel and come out of the forest with saoirse, liberty in your soul.

It is such a gift to the human body. It becomes a hospital for your soul. And then you are ready to go on with your life.”

The ancient Celtic ways did involve some expressions of hierarchical structures (a caste system and multi-generational “noble family” bloodlines etc.) and there are other aspects of the ancient Celtic culture that appear, to me, to not be fully aligned with Voluntaryism. However, I still feel there is a lot of wisdom to be gleaned from parts of their philosophy, their ways of organizing communities and how they incentivized behavior based in integrity and reverence for nature.

Some select pages:

For more information:

"For nearly a millennium, the Irish lived without a state under a legal system known as Brehon Law.”

https://www.libertarianism.org/podcasts/portraits-liberty/when-ireland-was-stateless

Another group of ancient cultures that offers us wisdom on our quest to choose "the green path" and co-create a future worth living in and gifting to future generations is Haudenosaunee Confederacy.

The Seventh Generation Principle is an Indigenous Concept, to think of the 7th generation coming after you in your words… work and actions, and to remember the seventh generation who came before you.

This concept is based on an ancient philosophy of the Haudenosaunee Confederacy (Iroquois).

As I stated in a recent post, when I broach the topic clearcutting forests and/or lithium mining, suggesting that we have an option that many are not willing to consider (going back to basics) with people who place anthropocentric and material concerns as their highest priority and bring up the reality that indigenous people’s lived here for millennia without any money and lived lives fulfilling lives of purpose, some of them use the red herring tactic of pointing to isolated instances where specific indigenous tribes used to engage in the sacrifice of animals, human beings or some other unpleasant behavior. They say things like “what you want us to go back in time to living in mud huts and human sacrifices???”

Some people attempt to use this red herring tactic when I bring up the above described Druids and they often engage in similar attempts to demonize and dismiss when I bring up the peoples who are indigenous to Turtle Island.

What many do not realize is that the information we have been indoctrinated into believing about so called “uncivilized” ancient cultures (such as the Druids/Celts and the Indigenous peoples of Turtle Island where I live) is simply lies, intentionally derogatory generalizations and propaganda.

History is written by the victors and those Roman and British empires who pillaged and destroyed the lands and peoples like the Druids of the British isles and First Nations of Turtle Island wanted to dehumanize and denigrate the image of those they slaughtered to make themselves feel and look better.

That being said, I do think that placing any culture, group of people or individual on some pedestal as pure is unhealthy. I feel we should be vigilant to make sure we are not romanticizing their past nor romanticizing the potential of their worldviews to provide solutions to the present challenges we face.

I acknowledge conflicts and rituals that existed in the Druidic ways and between the various indigenous tribes of what is now called North America, however I would suggest that we should keep in mind that demonization and dehumanization of the perceived “enemy” or targeted “sub-human class” of an empire is a time tested psychological warfare technique that has been employed in both real time conflicts and retrospectively as “victors write the history books”.

My response to such two dimensional distraction tactics are to remind them that in truth, when examining the act of sacrificing living beings for irrational and/or nefarious reasons, we need look no further than the institutions and corporations that surround us now in the western world. Those are the institutions many of us champion as the bastions and exemplars of “civilized society”.

Westernized, so called “civilized” cultures sacrifice the old, the poor, the young and everything in between every day and in droves.

“Bloodshed and sacrifice. All day, every day, industrial scale.”

Factory farms, Sacrificing thousand of hectares of virgin ancient forest ecosystem (and all the beings that call those places home) in the name of “sustainable development”, Old people care homes injecting them with deadly mRNA concoctions and getting the little kids to line up for the same injections (resulting in thousands of them dying needlessly).

We do not live in a “civilized society”. That is brainwashing. We live in a society that covets profits and intellect over compassion and intuition and a society that champions competitiveness and callous domineering while seeing kindness as weakness.

This is a very sick and savage society we live in in the western modernized world, it is just covered with an array of masks wearing smiling faces, re-assuring us all how advanced, impressive, safe and cared for we all are.

All throughout history Statist empires sought to steal the land from and impose their will upon people who had chosen to live in close connection to the land and the forest by assigning them with the dehumanizing, condescending and derisive label of being "uncivilized"/"savage".

The etymological root of the word Civilization is derived from the Latin word civilis, which means civil. Other related Latin words are civis, meaning citizen, and civitas, meaning city.

Cities (at least here on Earth) are the phenomenon that involves an instance where so many humans and artificial human structures gather in one place, that the massive community is no longer able to produce enough food and raw material to sustain it's continued existence (necessitating massive areas of land being deforested, pillaged and mined elsewhere so that those raw materials can be shipped to the city and keep it functioning and growing).

Also, who is to say what is to be defined as "civilized" and what is "civil" ?

By what standards do we apply such labels?

As you will see as you continue reading below, according to many of the Europeans (Jesuit priests, military men etc) who were instrumental in colonizing/invading Turtle Island (aka "North America") the people who originally inhabited these lands were "uncivilized" and "savage".

However, those who take an honest look at modern day industrial society and those who also study the ways of the people's indigenous to Turtle Island know that to be a fallacy, nothing more than the sad superficial propaganda pushed by hubristic thugs looking to make themselves feel better about their mass murdering and thievery.

As Lyla astutely points out, this was/is not only true of how the statists sought to annihilate, assimilate and pillage the cultures and lands of the diverse peoples of Turtle Island. It was also true (and is still also true) for how statist regimes have sought (and continue to seek) to do the same to other people who lived (and live) in close relationship with the living Earth all over the world.

This was true of my blood ancestors in the Druidic (and then eventually Celtic) nations and it is true now in how the Canadian government and corporations are imposing their will upon those people who live in areas where profitable minerals exist in the ground that they want to get their hands on.

Many in modern times have been conditioned to see the ancient Druids and their Celtic predecessors the Brehon (Breitheamh) Judges.

The Druidic wisdom keepers encapsulated their combined memory of medicines, conflicts, natural disasters, geology, meteorology, pathways to peaceful resolution and stories that educate the listener about astronomy, mathematics and ecology into rhymed verse (often recited as part of a song with harps or flutes). Those concentrated expressions of their culture were passed down to the time of the Celts arriving and were then written down in Ogham on stone and wood to become the Brehon (Breitheamh) Laws (or Fenechus).

They had laws to honor and protect the bees and the trees and saw men and women as equals (long before anyone in Europe).

The first recordings of the Brehon (Breitheamh) Laws were made around the year 700 BC. They were collected (not invented) by a great Breitheamh (judge) named Ollamh Fodhla and inscribed into Ogham in stone and on elongated wooden panels. These were said to be the written form of laws, ways of seeing and knowledge with much more ancient roots and deep history in that land which was (up until then) passed down through the form of rhymes and verse (in the form of music).

The Roman church began attempting to erase that cultural history in the year 438 AD when monks were sent to gather all the Brehon laws (recorded on wooden panels and stone) and transcribe them (censoring that which did not align with the Christian views of the world and our place in it). The Christian statist interlopers gathered the sacred laws of the Breitheamh in Teamhair na Rí ('Tara of the kings'), and formerly also Liathdruim ('the grey ridge') and after transcribing them in what they described as a ”purified” form (meaning censored, altered and redacted) they destroyed all the original Ogham writing they could get their hands on. This attempt to steam roll the old Druidic ways and distort Brehon Law to serve as another tool for indoctrinating and assimilating the Celtic people failed as much of the Ogham which recorded the ancient knowledge was carved into large stones all over the land in hidden corners, cliffs and boulders.

The ancient knowledge keepers (Breitheamh or “Brehon” judges) of the time saw what the Roman Christian church was attempting to do and so they made sure to infuse their wisdom into verse “wrapped in a thread of poetry” and taught these songs to the bards and townsfolk far and wide to preserve the essence of their culture.

This wise covert approach to preserving their cultural wisdom persisted for well over a millennia until it again came under direct threat from statist regimes that sought to erase the past and impose their degenerative involuntary governance structures upon the Celtic tribes.

That is why the statists of the British monarchy (queen Elizabeth) ordered her thugs to "Hang harpers, wherever found, and destroy their instruments".

Harpers, however, were not the only Irish treated with such hostility. In an attempt to gain control of Ireland, laws were enacted by the English Crown making it illegal for the Irish to speak their language, own land, become educated and to marry. The penalty was death.

This forbidding of the bards from reciting their verses in their native Gaelic tongue (under penalty of death) was similar to how the Canadian Government would later force the First Nation children of Turtle Island into concentration camps (euphemistically called “residential schools”) cutting off their hair, forbidding them to speak their language and thus attempting to sever the hereditary line of knowledge which was passed down in verbal stories in their own language.

Between 1650 and 1660, Oliver Cromwell ordered the destruction of harps and organs. Harps were burned and harpers were forbidden to congregate. Despite this, various records indicate that some Highland chiefs retained their harpers well into the eighteenth century, and place names such as Harper’s Pass, Harper’s Field (both on the island of Mull), Harper’s Window (Isle of Skye) and Harper’s Gallery (Castlelachlan in Argyle) remind us of the one-time importance of the harp in these areas.

For more information: https://harpmuse.com/harp-history?fbclid=IwAR2Rmb6e4K368aaAaxg5hzy9j7JaAP5Ug8wahOEDrdH8oou4gFfYwlxK4Aw

The time has come for us to ask ourselves the question, Have we been tricked by "Civilization"? and where do our true allegiances lie?

Do we swear our allegiance to a flag/nation state/"civilization" or do we swear our allegiance to the Living Earth?

As I have clearly outlined in this essay , there is no middle road in answering that question, because one is antithetical to the other.

With all that being said, I would also like to highlight the fact that psychopathy, greed and other anti-social traits are not unique to modern western culture. Unpleasant, selfish (and even sometimes ecologically degenerative) characteristics can be observed (overtly) in the traditions of specific isolated indigenous peoples (some of them were slave trading warlords and others may have respected the forest but were somewhat materialistic coveting ornate possessions).

Other indigenous peoples of Turtle Island refused to trade with people that enslaved others and wanted nothing to do with money (as was the case with some of the people that will be described in the excerpts I will share below who called the Eastern Woodlands, where I now live, home).

I feel that while no culture is perfect, and some may have lived in a way that expressed more compassion, ethical social structures and holistic thinking than others, one thing is certain, and that is that these starkly contrasted cultures offer us helpful sign posts as we attempt to navigate and forge a path towards a more honest, equitable, kind, abundant and regenerative future.

While the argument made in the image above certainly holds merit, that book does not really explore the actual examples of stateless societies which it alluded have in fact existed.

Above I explored one example of an expression of a society that functioned for many centuries (if not millennia) without a centralized state (the Celtic/Druidic tribes) now I would like to shift our attention over to Turtle Island (aka “North America”) to explore the expressions of stateless societies that existed in these lands prior to European colonization.

As you will see when you read ahead, it was not only the Europeans that were bewildered, taken back and often critical when they made contact with the Indigenous peoples of Turtle Island and began to live along side of them.

Most of our history books only look at the equation from the perspective of the so called “explorers” (aka thugs looking to find more land to take from other humans and natural abundance to plunder) and how these interlopers on the shores of Turtle Island viewed the indigenous inhabitants with contempt (often referring to them when dehumanizing and derisive labels such as “savages”) but it turns out that the indigenous peoples were equally (if not more appalled and disgusted) by the way the Europeans lived and organized their society.

I will leave it to you to decide who’s disgust was more justified as you read the excerpt below.

The sections of the book I share below offer the observations and view points of both indigenous scholars and their counterparts (Jesuit missionaries/military officers etc).

Below I will share a few excerpts from a book titled “The Dawn of Everything” by David Graeber and David Wengrow.

In essence, I agree with Crow Qu’appelle (of Nevermore Media) when he said that the book does have several gaping omissions, but it also “essentially completely revolutionizes the history of the Western intellectual tradition, including the Enlightenment, natural law theory, and more.

It really is a very significant contribution to the project of un-whitewashing history.

The major achievement of Graeber and Wengrow is to restore what they call The Indigenous Critique (of Western Civilization) to its proper place in history.

What is the indigenous critique, you ask? Well, basically, when Europeans arrived to Turtle Island, they encountered very different societies than those they were accustomed to. Those societies had very different cultures, each with their own intellectual tradition.

The collision of two completely separate intellectual traditions led to the creation of an indigenous critique of European society, which Graeber and Wengrow call The Indigenous Critique.

The Indigenous Critique refers to critiques of European society which were developed by Turtle Islanders.”

Elizabeth Whitworth explains:

“In the late 1600s, European colonists in North America became engaged in philosophical discussions with the indigenous peoples of that land. Some of the indigenous people and the colonists learned to speak one another’s languages fluently. Graeber and Wengrow explain that the native North Americans had strong philosophical traditions and skilled orators who challenged European colonial officials in debates.”

In some cases, indigenous intellectuals travelled to Europe in order to study and understand feudal society. One such person was a Huron-Wendat leader named Kondiaronk, also known as Le Rat, who seems to have impressed everyone he ever met with his great brilliance.

Whitworth continues:

“In New France, Wendat leader Kandiaronk raised scathing critiques of European social customs and values, particularly criticizing monarchical rule, social hierarchies, emphasis on the accumulation of wealth and materialism, and punitive justice systems. These descriptions then made their way back to Europe, where they were widely distributed among the intellectual class and, Graeber and Wengrow argue, became the inspiration for much Enlightenment thought.

One of the major cultural differences the Europeans and indigenous people found they had was the notion of equality and its connection to freedom. Indigenous ideas about equality and freedom directly conflicted with the European notions of social status and a natural hierarchy.

Graeber and Wengrow say that Europe before the 1700s lacked a notion of social equality. They believed that some people are naturally higher or lower in status and authority than others. They lived in monarchies and they derived that system from biblical notions of nobility and authority. In other words, “God” (aka the church) decided one’s station in life.

By contrast, many of the Native American cultures had no notion that anyone could be born higher or lower in status than anyone else or that anyone could have authority over anyone else. In such cultures, status might be gained with age or according to merit. But the notion that people are inherently unequal or that any status could give someone the right to dominate someone else would not have existed in this kind of cultural worldview.”

After visiting France and then returning to the Eastern Woodlands of Turtle Island Kondiaronk (the Wendat chief described above) offers this distillation of the indigenous critique:

“I’ve spent six years thinking about the state of European society and I still can’t think of a single one of your ways that isn’t inhumane, and I sincerely believe that it can only be because you stick to your distinctions of ‘mine’ and ‘yours’.

I affirm that what you call money is the devil of devils; the tyrant of the French, the source of all evil; the scourge of souls and the slaughterhouse of the living. To imagine that one can live in the land of money and preserve one’s soul is like imagining that one can preserve one’s life at the bottom of a lake. Money is the father of luxury, lasciviousness, intrigue, deceit, lies, betrayal, insincerity, all the worst behaviors in the world. Fathers sell their children, husbands their wives, wives betray their husbands, brothers kill each other, friends are false, and all for money. In light of all this, tell me that we Wendat are not right to refuse to touch or even look at money?”

Kandiaronk continues, explaining human qualities valued by the Wendat by saying:

“Over and over I have set forth the qualities that we Wendat believe ought to define humanity – wisdom, reason, equity, etc. – and demonstrated that the existence of separate material interests knocks all these on the head. A man motivated by interest cannot be a man of reason. “

Kandiaronk’s view was that the greed, poverty, and crime found in French society arise from lust for money. By refusing to deal with money, the Wendat were able to live in freedom and equality.

Kandiaronk:

“Do you seriously imagine, he says, that I would be happy to live like one of the inhabitants of Paris, to take two hours every morning just to put on my shirt and make-up, to bow and scrape before every obnoxious galoot I meet on the street who happened to have been born with an inheritance? Do you really imagine I could carry a purse full of coins and not immediately hand them over to people who are hungry; that I would carry a sword but not immediately draw it on the first band of thugs I see rounding up the destitute to press them into naval service?”

In other words, one of the most important thinkers in the history of the Western intellectual tradition was an indigenous man (that might aptly be described in today’s terms as an anarchist) from what’s now the eastern woodlands of “Canada”.

Beyond the emphasis of the indigenous critique on the immorality of the hierarchical and involuntary governance structures (Statism) that was prevalent in Europe (and being imported to Turtle Island with the settlers/colonial peoples) many of the people who called Turtle Island home were also very critical of the lack of compassion, generosity and charity which was ubiquitous in the European’s way of living.

The ideals of the French Revolution — liberty, equality and fraternity — took the form they did in the course of just such a long series of debates and conversations. Graeber and Wengrow suggest that those conversations stretched back further than Enlightenment historians assume.

In their book they invite us to consider:

What did the inhabitants of New France make of the Europeans who began to arrive on their shores in the sixteenth century?

At that time, the region that came to be known as New France was inhabited largely by speakers of Montagnais-Naskapi, Algonkian and Iroquoian (Potawatomi) languages. Those closer to the coast were often fishers, foresters and hunters, though most also practiced horticulture (and regenerative agro-forestry); the Wendat (Huron), concentrated in major river valleys further inland, growing maize, squash and beans around fortified towns..

..While French assessments of the character of (what they described as) ‘savages’ tended to be decidedly mixed, the indigenous assessment of French character was distinctly less so.

Father Pierre Biard, for example, was a former theology professor assigned in 1608 to evangelize the Algonkian-speaking Mi’kmaq in Nova Scotia, who had lived for some time next to a French fort.

Biard did not think much of the Mi’kmagq, but reported that the feeling was mutual:

“They consider themselves better than the French: “For,” they say, “you are always fighting and quarrelling among yourselves; we live peaceably. You are envious and are all the time slandering each other; you are thieves and deceivers; you are covetous, and are neither generous nor kind; as for us, if we have a morsel of bread we share it with our neighbor.” They are saying these and like things continually.’“

What seemed to irritate Biard the most was that the Mi’kmaq would constantly assert that they were, as a result, ‘richer’ than the French. The French had more material possessions, the Mi’kmaq conceded; but they had other, greater assets: ease, comfort and time.

Twenty years later Brother Gabriel Sagard, a Recollect Friar,” wrote similar things of the Wendat nation. Sagard was at first highly critical of Wendat life, which he described as inherently sinful (he was obsessed with the idea that Wendat women were all intent on seducing him), but by the end of his sojourn he had come to the conclusion their social arrangements were in many ways superior to those at home in France.

In the following passages he was clearly echoing Wendat opinion:

“They have no lawsuits and take little pains to acquire the goods of this life, for which we Christians torment ourselves so much, and for our excessive and insatiable greed in acquiring them we are justly and with reason reproved by their quiet life and tranquil dispositions.”

Much like Biard’s Mi’kmaq, the Wendat were particularly offended by the French lack of generosity to one another:

‘They reciprocate hospitality and give such assistance to one another that the necessities of all are provided for without there being any indigent beggar in their towns and villages; and they considered it a very bad thing when they heard it said that there were in France a great many of these needy beggars, and thought that this was for lack of charity in us, and blamed us for it severely.’

Sagard’s account of his stay among the Wendat became an influential bestseller in France and across Europe: both Locke and Voltaire cited Le grand voyage du pays des Hurons as a principal source for their descriptions of Turtle Island (indigenous) societies. The multi-authored and much more extensive Jesuit Relations, which appeared between 1633 and 1673, were also widely read and debated in Europe, and include many a similar remonstrance aimed at the French by Wendat observers..

I feel it is worth highlighting here that, the indigenous Turtle Islander’s attitudes are likely to be far closer to many of our attitudes (as modern day people) than seventeenth-century European ones.

These differing views on individual liberty are especially striking. Nowadays, it’s almost impossible for anyone living in a so called ‘liberal democracy’ to say they are against freedom — at least in the abstract (in practice, of course, our ideas are usually much more nuanced). This is one of the lasting legacies of the Enlightenment and of the American and French Revolutions. Personal freedom, we tend to believe, is inherently good (even if some of us also feel that a society based on total individual liberty — one which took it so far as to eliminate police, prisons or any sort of apparatus of coercion — would instantly collapse into violent chaos). Seventeenth-century Jesuits most certainly did not share this assumption. They tended to view individual liberty as animalistic. In 1642, the Jesuit missionary Le Jeune wrote of the Montagnais-Naskapi:

“They imagine that they ought by right of birth, to enjoy the liberty of wild ass colts, rendering no homage to any one whomsoever, except when they like. They have reproached me a hundred times because we fear our Captains, while they laugh at and make sport of theirs. All the authority of their chief is in his tongue’s end; for he is powerful in so far as he is eloquent; and, even if he kills himself talking and haranguing, he will not be obeyed unless he pleases the Savages.

..From the beginning of the world to the coming of the French, the Savages have never known what it was so solemnly to forbid anything to their people, under any penalty, however slight. They are free people, each of whom considers himself of as much consequence as the others; and they submit to their chiefs only in so far as it pleases them.”

In the considered opinion of the Montagnais-Naskapi, however, the French were little better than slaves, living in constant terror of their superiors. Such criticism appears regularly in Jesuit accounts; what’s more, it comes not just from those who lived in nomadic bands, but equally from townsfolk like the Wendat. The missionaries, moreover, were willing to concede that this wasn’t all just rhetoric on the Americans’ part. Even Wendat statesmen couldn’t compel anyone to do anything they didn’t wish to do. As Father Lallemant, whose correspondence provided an initial model for The Jesuit Relations, noted of the Wendat in 1644:

I do not believe that there is any people on earth freer than they, and less able to allow the subjection of their wills to any power whatever — so much so that Fathers here have no control over their children, or Captains over their subjects, or the Laws of the country over any of them, except in so far as each is pleased to submit to them. There is no punishment which is inflicted on the guilty, and no criminal who is not sure that his life and property are in no danger…”

Lallemant’s account gives a sense of just how politically challenging some of the material to be found in the Jesuit Relations must have been to European audiences of the time, and why so many found it fascinating.

After expanding on how scandalous it was that even murderers should get off scot-free, the good father did admit that, when considered as a means of keeping the peace, the Wendat system of justice was not ineffective. Actually, it worked surprisingly well.

Rather than punish culprits, the Wendat insisted the culprit’s entire lineage or clan pay compensation. This made it everyone’s responsibility to keep their kindred under control. ‘It is not the guilty who suffer the penalty,’ Lallemant explains, but rather ‘the public that must make amends for the offences of individuals.’ If a Huron had killed an Algonquin or another Huron, the whole country assembled to agree the number of gifts due to the grieving relatives, ‘to stay the vengeance that they might take’.

Wendat ‘captains’, as Lallemant then goes on to describe, ‘urge their subjects to provide what is needed; no one is compelled to it, but those who are willing bring publicly what they wish to contribute; it seems as if they vied with one another according to the amount of their wealth, and as the desire of glory and of appearing solicitous for the public welfare urges them to do on like occasions.’ More remarkable still, he concedes: ‘this form of justice restrains all these peoples, and seems more effectually to repress disorders than the personal punishment of criminals does in France,’ despite being ‘a very mild proceeding, which leaves individuals in such a spirit of liberty that they never submit to any Laws and obey no other impulse than that of their own will’.

The Jesuits all continually emphasized, merely holding political office did not give anyone the right to give anybody orders either. Or, to be completely accurate, an office holder could give all the orders he or she liked, but no one was under any particular obligation to follow them.

To the Jesuits, of course, all this was outrageous. In fact, their attitude towards indigenous ideals of liberty is the exact opposite of the attitude most French people or Canadians tend to hold today: that, in principle, freedom is an altogether admirable ideal. Father Lallemant, though, was willing to admit that in practice such a system worked quite well; it created ‘much less disorder than there is in France’ — but, as he noted, the Jesuits were opposed to freedom in principle:

“This, without doubt, is a disposition quite contrary to the spirit of the Faith, which requires us to submit not only our wills, but our minds, our judgments, and all the sentiments of man to a power unknown to our senses, to a Law that is not of earth, and that is entirely opposed to the laws and sentiments of corrupt nature. Add to this that the laws of the Country, which to them seem most just, attack the purity of the Christian life in a thousand ways, especially as regards their marriages.”

The Jesuit Relations are full of this sort of thing: scandalized missionaries frequently reported that American women were considered to have full control over their own bodies, and that therefore unmarried women had sexual liberty and married women could divorce at will. This, for the Jesuits, was an outrage. Such sinful conduct, they believed, was just the extension of a more general principle of freedom, rooted in natural dispositions, which they saw as inherently pernicious. The ‘wicked liberty of the savages’, one insisted, was the single greatest impediment to their ‘submitting to the yoke of the law of God’ (aka the orders given by the church). Even finding terms to translate concepts like ‘lord’, ‘commandment’ or ‘obedience’ into indigenous languages was extremely difficult; explaining the underlying theological concepts, well-nigh impossible.”

The Jesuit Relations provided detailed accounts of the counter-arguments and objections to Christian dogma that they encountered, and numerous missionaries commented on how impressed they were by the intelligence of the Turtle Islanders.

Father Le Jeune, Superior of the Jesuits in Canada in the 1630s, wrote:

There are almost none of them incapable of conversing or reasoning very well, and in good terms, on matters within their knowledge. The councils, held almost every day in the Villages, and on almost all matters, improve their capacity for talking.

Or, in Father Lallemant’s words:

“I can say in truth that, as regards intelligence, they are in no wise inferior to Europeans and to those who dwell in France. I would never have believed that without instruction, nature could have supplied a most ready and vigorous eloquence, which I have admired in many Hurons; or more clear-sightedness in public affairs, or a more discreet management in things to which they are accustomed.”

Another remarked:

They nearly all show more intelligence in their business, speeches, courtesies, intercourse, tricks, and subtleties, than do the shrewdest citizens and merchants in France.

It’s worth noting that the Jesuits were the intellectuals of the Catholic World. They were trained in logic, rhetoric, linguistics, theology, and many other thing besides. But missionaries often found themselves no match for the wit of their indigenous interlocutors.

Graeber and Wengrow note:

Jesuits, then, clearly recognized and acknowledged an intrinsic relation between refusal of arbitrary power, open and inclusive political debate and a taste for reasoned argument. It’s true that Native American political leaders, who in most cases had no means to compel anyone to do anything they had not agreed to do, were famous for their rhetorical powers. Even hardened European generals pursuing genocidal campaigns against indigenous peoples often reported themselves reduced to tears by their powers of eloquence.

While discovering the historical details of the so called “indigenous critique” has filled in some important pieces of the puzzle for me and sections of the book help to show how (in contrast to colonial propaganda about “savages”) indigenous societies offered their own intellectual perspectives (which some might even describe as superior or more holistic than those originating in Europe at the time) the book also talks about the indigenous peoples that lived along the Mississippi River, what is now called California, Northeastern Canada and Northwestern Canada and refers to them as “hunter/gatherers and/or foragers”. This, to me, either shows that the book was edited/censored/watered down, or that the authors appear to know very little about how many indigenous people cultivated food.

I have seen evidence from multiple sources that people who called those lands home actually had extremely advanced food cultivation and farming systems that seamlessly blended with existing forest ecology.

Thus, they did not simply forage, but rather actively managed (and even enhanced ecosystems biodiversity) in order to produce an abundance of nutrient dense food (and in a way that expresses an advanced understanding of botany, the interdependence of species and soil ecology).

Here is a link to a video presentation that explores of those ancient methods

“Architects of Abundance: Indigenous Food Systems and the Excavation of Hidden History” by Dr. Lyla June

Here is Lyla June’s Dissertation on that subject if you are interested in learning more on the nitty gritty data side of things : https://www.proquest.com/openview/17597a179528716e1a9e8515ca76ec77/1?pq-origsite=gscholar&cbl=18750&diss=y

I share the above excerpts from that book to highlight how

A: the inhabitants of Turtle Island rightfully and astutely observed that a life spent focusing on gathering money (whether to horde it or to buy things, including not only things like food, but the loyalty/servitude of other human beings) can lead to unhealthy psychological and societal manifestations.

and B: How involuntary governance structures are not necessary and are actually systems that result in more violence, greed, fear and thievery as opposed to voluntary and/or quasi-anarchist societies.

I offer this glimpse into perspectives on some of the cultures of Turtle Island and how they were described by the colonists/missionaries as never allowing a neighbor to starve, not being beholden to any other human’s orders and able to live fulfilling lives (without an involuntary governance structure and without a centralized food production/distribution system) in the hopes it might offer us the chance to take an honest look in the mirror and ask ourselves:

“If the way our modern society is structured and how people prioritize selfishness and greed is not human nature, but rather is learned and conditioned behavior, how can we begin to de-program ourselves and nurture a more equitable, abundant, charitable and magnanimous society?”

No ancient culture was perfect, and the Druidic ways/Celtic tribes and indigenous peoples of Turtle Island are no exceptions. That being said, perhaps we can glean some wisdom from the worldviews embodied in the language and culture of the indigenous peoples of Turtle Island as well as the Druids and the Celtic tribes to find common ground as we strive to cultivate freedom and cultivate Voluntaryism in our modern communities?

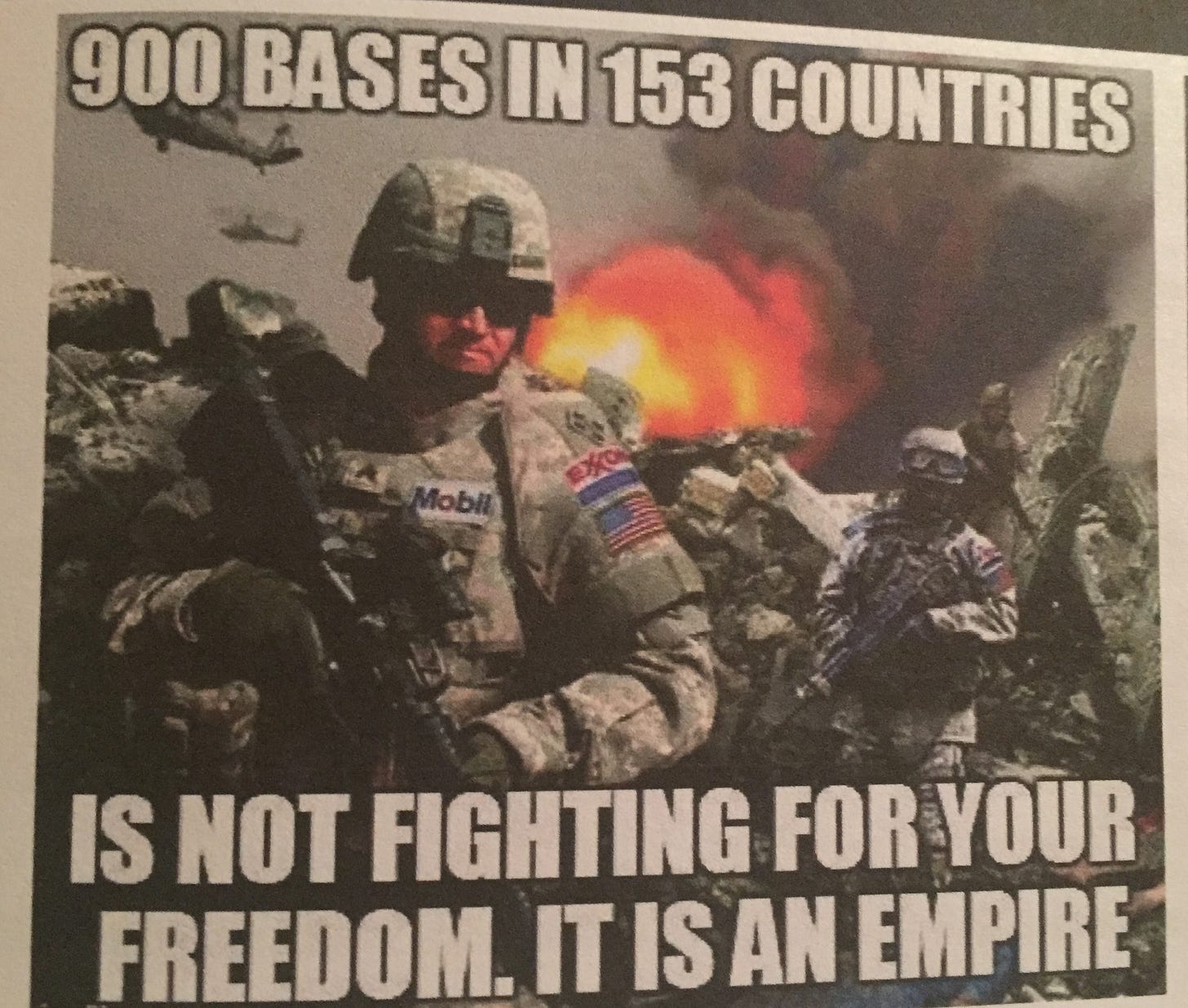

Now let us explore the example of the Loess Plateau in China and look at the numbers required to make that ecosystem restoration project happen as compared to the quantity of money that is extracted from the population through violent coercion (taxation) and either squandered or used to pad the pockets of various racketeering cartels such as weapons manufacturers and pharmaceutical cartels.

“One of the most impressive desertification reversal projects is the Loess Plateau Watershed Rehabilitation Project in northern China, made famous by filmmaker John D. Liu. The loess plateau of this region was a cradle of civilization, exceeded only by Mesopotamia in its antiquity, and suffering a similar fate. According to Liu, by the year 1000 deforestation and unsustainable agricultural practices had reduced a lush land of forests and grasslands to a parched, eroded wasteland that looks like a desert even though it receives modest rainfall. That is because 95 percent of it runs off immediately, forming huge erosion gullies and giving the Yellow River its characteristic color.

The results of the rehabilitation project can be seen in Liu’s stunning before-and-after photographs—the land has literally come back to life. The change came through a huge investment of labor, money, and planning. Local residents were recruited in large numbers to build small earthen dams, terraces, and other water retention features. They planted trees, abandoned slopelands unsuitable for planting, and restricted the grazing of sheep and goats. Crucially, they closely participated in the planning of the project as well, and were given subsidies for their labor and granted land rights to restored areas. In the end, an area of 35,000 square kilometers (the size of Belgium) was restored at a cost of about half a billion dollars. The written word cannot do justice to the changes that transformed the landscape, but Liu’s film has inspired similar projects in Rwanda, Ethiopia, Jordan, and other countries.

These projects show what is possible when the collective human will is brought into alignment with Earth’s capacity to heal. It shows what is possible when we make a collective choice toward beauty rather than quantity. And here is the caveat—it does require will, an active choice. Otherwise, we will continue to slide in the direction of our inertia.

Is something like this possible globally? Is it practical? Realistic? No, if we accept the permanence of society as we know it. Yes, if we are prepared to let go of what had seemed unchangeable. A half billion dollars over ten years is nothing in comparison with, say, global military budgets, which total about 3,300 times that. Devoting just 10 percent of military spending to watershed restoration would fund 330 loess-sized projects. Earth is actually not asking very much of us.

All right, I admit it, that last sentence is a bit disingenuous. Earth is asking a lot of us. Earth is demanding a transformation of our civilization’s fundamental priorities. Earth is demanding that we see her as sacred. Earth is demanding that we see her as alive. Earth is demanding we reorder our civilization and all its institutions accordingly. Money, government, law, technology … all must change. That is why the ecological crisis is truly an initiation for humanity.”

- Charles Eisenstein (from Climate — A New Story, Chapter 8: Regeneration, “Healing the Water”.

So as you can see, the money we have taken from us under threat of violence (whether we want to fund wars or not) that is given to war profiteers could be reduced by only 10% and it would fund hundreds of Loess Plateau sized restoration projects, yet despite what I expect you (and I certainly also think) is the ethical way for that money to be spent, it is instead used to pay for bullets, bombs, landmines, missiles and deadly drones which can kill people in far away lands (so that those in a position to profit from stealing their resources or imposing debt schemes on their economies, can continue to do so).

Such are the inevitable unfortunate results of involuntary governance structures.

Ok, so now we can see how our money is taken from us by involuntary governance systems to fund murdering poor people in far away lands to further the interests of plutocrats (instead of funding things that we would actually want to donate our money towards, such as regenerating huge areas of desertified and deforested land) but what other ways does the State squander our hard earned dollars in tax money (which could be used for noble endeavors such as ecosystem regeneration if those funds were not being stolen from us)?

Well, unfortunately, national governments are not the top tier of the transnational racketeering cartel that squeezes us all for “protection money”.

Above nation states (and their various mid level politician plutocrats, revolving door regulators and congressional/senate war profiteers) there is the international central banking cartel. These are criminal syndicates that have dominated the policies of nation-states for close to a century in the west and they extract massive amounts of interest on the predatory loans which the statist goons in our governments agree to (on our behalf and without our consent).

In the fiscal year of 2005 total individual income taxes in the U.S. totaled $927 Billion. Of that amount $352 Billion (or 38%) was required to pay interest on the federal debt. That figure would be significantly higher now. It is forecasted that the individual income tax which will be collected from US citizens in 2019 will total approximately $1.824 trillion, meaning approximately $693.1 Billion of that will go to the private central bankers and similar numbers are reflected here in Canada (relative to our respective population density).

That means that in 2005 that previously mentioned $352 Billion dollars of hard earned tax money was paid to the transnational bankers who own the Federal Reserve.

None of the $352 Billion dollars went into the infrastructure of the United States (as most statists believe it did) it was extracted from the tax payers through violent coercion by the government and then given to private interests who have a legal monopoly to print money (serving to make a small group of families even richer).

That money could have paid for 2344 Loess Plateaus projects (a large scale eco-system and soil regeneration project described in the videos above) but instead that money went to people who did zero work for that money and received that money as profit thanks to the legislation that was signed by President Woodrow Wilson in 1913.

How many of the general public do you think would have voted for that tax money to be used to fund 2344 Loess Plateau sized ecological regeneration projects (rather than giving that money to the transnational banking cartel as interest accrued on a debt none of us ever agreed to)?

If it is the will of the people for their collective energy to be funneled towards regeneration, what stands in the way?

The answer is simple, it is the Statist system that covet profits, control and commodification of nature.

Since there are some that may be reading this who reject that human activities are posing any serious impact or damage to the biosphere and embrace the “techno optimist” position that modern human civilization is a gem worth cherishing and that we can use our endless innovative technological genius to “sustainably develop” our way out of any challenges we face, I present the following excerpt.

“I have referenced the idea that human well-being and planetary health are inextricably connected, and that no such future is possible. I will now explore the opposite idea: that human ingenuity is unlimited, as is our capacity to replace ecosystem services with technological substitutes.

In other words, what if the version of the Story of Interbeing I’ve given you is wrong? What if we can, in fact, forever insulate ourselves from the effects of our actions?

This passage evokes a nightmare world where the entire biosphere has been converted to a giant feedlot and industrial park, where we manage the planet like a machine with technological tweaks to its gross material components, where no species exists that has not been turned to human purposes. It is a world wholly toxic to life except within artificially maintained enclaves. It is a world of vat-grown meat, computerized hydroponic greenhouses instead of farms, algae pools for oxygen, carbon-sucking machines to regulate the atmosphere, desalinization plants, climate-controlled air-filtered bubble cities, and a planetary surface converted to one huge mine and garbage dump. In that world, human life becomes entirely dependent on technology, as we retreat from the ugliness we have wrought into an artificial or even a virtual environment. Can you say this isn’t already under way? This is not a world I would want to live in. No one would, yet for thousands of years, humanity in aggregate has proceeded choice by choice, step by step toward a Concrete World. I would like to dismiss it as impossible on ecological grounds, but what if it is possible? What if, instead of being compelled to reject it, we must consciously choose a different path?

Climate activists are fond of saying, “We are going to have to change now.” Maybe the significance of climate change is not “Change or perish,” but an invitation to reorient civilization toward beauty rather than quantity. Starkly confronting us with the results of our power, it asks, “What kind of world do you want to live in?”

Whether or not endless technological adaptation to an ever-more-degraded ecosystem is actually possible, the perception that it is possible indeed presents us with the necessity of making a conscious choice. If ecological degradation had the power to force us to choose a healing path, it would have happened already. Therefore, that choice to take the healing path will have to be made on some basis other than compulsion. It will not come through fear of personal or civilizational extinction.

I want to repeat: if ecological degradation had the power to force us to choose a healing path, it would have happened already.

Is the choice to heal ever really forced on us? Some people quit smoking on the first diagnosis of lung disease; others persist in smoking through their tracheostomy hole even as lung cancer wracks their body. What is happening when we reach that critical moment where we hit bottom, where the old life becomes intolerable? When do we say, “Enough. I’m out of here”? When do we finally quit that job, leave that relationship, take that journey, quit that addiction, release that grudge? Usually a course reversal toward wholeness is sparked by some kind of crisis, but it is not guaranteed by one. Each crisis, each tragedy, each new injury or loss is an invitation onto a different path. It is up to us to accept that invitation.

As the deterioration of the biosphere proceeds, we will surely face many crises, tragedies, and losses. If fear of further loss is not enough to change our course, what is? The dominant environmental narrative, especially when it comes to climate, is based on fear of consequences for humanity. What do we choose from when we don’t choose from that fear?

Most people will offer love as the antipode of fear. I’m wary of this formula, which veers close to replicating the familiar paradigm of good versus evil. Fear is not always a bad thing; sometimes it can heighten one’s wakefulness and focus, and catalyze action. That action might be in service of those we love; it needn’t be in service of self-preservation. We care about what we love, even when that caring in no rational way contributes to our measurable benefit. Sometimes we even sacrifice our lives for what we love. Love makes us care more passionately than self-interest can, and, as Dr. Seuss put it in The Lorax, “Unless we begin caring a whole awful lot, nothing is going to get better. It’s not.” Nature might not save us from ourselves.

So the care we need to live in a more beautiful world comes from love. But how does love awaken? One way is through loss, grief, and the realization of death. When a friend or family member falls ill or has a near brush with death, or enters into the dying process, the reality of their preciousness overcomes my holding patterns and opens me to deeper care. Unfortunately, these holding patterns have a powerful ally in modern society’s denial of death—its fetish for youth, preservation, and growth. Denial of death holds life at bay too. It usurps love and enthrones the pretender we call ego. Modern civilization upholds an equivalent pretense in its ideology of human exceptionalism: that human beings and human society can be exempt from limits. The untrammeled growth of the separate self, whether the personal self or the collective human self, is inimical to love. Therefore, death, loss, and grief are love’s allies.

Another partner of love, in its awakening and its expression, is beauty. We fall in love with what is beautiful, and we see beauty in what we love. Let us consider beauty then to replace utilitarian benefit as the motivation and aim of humanity’s relation to the world. Whether or not a world of rats and concrete is survivable, it is definitely not as beautiful as the “once and future world” that MacKinnon describes.[6] Explorers and naturalists of previous centuries give staggering testimony to the incredible natural wealth of North America and other places before colonization. Here are some images from another book, Steve Nicholls’s Paradise Found:

'Atlantic salmon runs so abundant no one is able to sleep for their noise. Islands “as full of birds as a meadow is full of grass.” Whales so numerous they were a hazard to shipping, their spouts filling the entire sea with foam. Oysters more than a foot wide. An island covered by so many egrets that the bushes appeared pure white. Swans so plentiful the shores appear to be dressed in white drapery. Colonies of Eskimo curlews so thick it looked like the land was smoking. White pines two hundred feet high. Spruce trees twenty feet in circumference. Black oaks thirty feet in girth. Hollowed-out sycamores able to shelter thirty men in a storm. Cod weighing two hundred pounds (today they weigh perhaps ten). Cod fisheries where “the number of the cod seems equal that of the grains of sand.” A man who reported “more than six hundred fish could be taken with a single cast of the net, and one fish was so big that twelve colonists could dine on it and still have some left.”

I used the word “incredible” advisedly when I introduced these images. Incredible means something like “impossible to believe”; indeed, incredulity is a common response when we are confronted with evidence that things were once vastly different than they are now. MacKinnon illustrates this phenomenon, known in psychology as “change blindness,” with an anecdote about fish photographs from the Florida Keys. Old photographs from the 1940s show delighted fishermen displaying their prize catches—marlins as long as a man is tall. When present-day fishermen see those pictures, they flat-out refuse to believe they are authentic.

Human beings tend to be blind to gradual changes in their environment, assuming that the way things are right now is how they always have been and always will be. We do not miss the former beauty of the world, he would say, because we have never known it.

I am not so sure that we don’t miss it. I think we do miss it, but we don’t know what it is we are missing. We feel a void, a sense of poverty, a hunger for something unidentifiable. Transferred onto money or consumer items, that hunger drives continued cycles of destruction. Transferred onto drugs, gambling, alcohol, it drives the unsolvable social problem of addiction. Perhaps the degradation of nature is not without its consequences after all.