Serviceberry - a secret treasure of the north

Exploring the many gifts offered by the Service Berry in the context of Food Forest Design. This is Installment #3 of the Stacking Functions in the Garden, Food Forest and Medicine Cabinet series.

This post serves as the second crossover post which is both part of the above mentioned (Stacking Functions in the Garden, Food Forest and Medicine Cabinet : The Regenerative Way From Seed To Apothecary series) as well as constituting the 5th installment of the Befriending The Boreal series.

Amelanchier (aka Serviceberry, Shadbush, Sasakatoon Berry)

Family: ROSACEAE

Part used for medicine/food: Berries/Seeds, leaves, stems, and roots

Constituents:

Vitamins found in saskatoon berries include vitamin C, thiamin, riboflavin, pantothenic acid, vitamin B-6, folate, magnesium, phosphorus, vitamin A and vitamin E. Phenolic compounds, particularly the anthocyanins, are the major functional components of saskatoon berries. There are at least four anthocyanins in ripe saskatoon berries of which cyanidin 3-galactoside and 3-glucoside account for about 61% and 21% of the total anthocyanins, respectively. Other phenolic compounds characterized include cyanidin 3-xyloside, quercetin, catechins, cinnamic acids, chlorogenic acid, lutein or zeaxanthin and rutin. Anthocyanin content of saskatoon berries ranges from 25 to 179 mg/100 g of berries and total phenolics range from 0.17% to 0.52%.

Amygdalin (or vitamin B17) is found in the seeds.

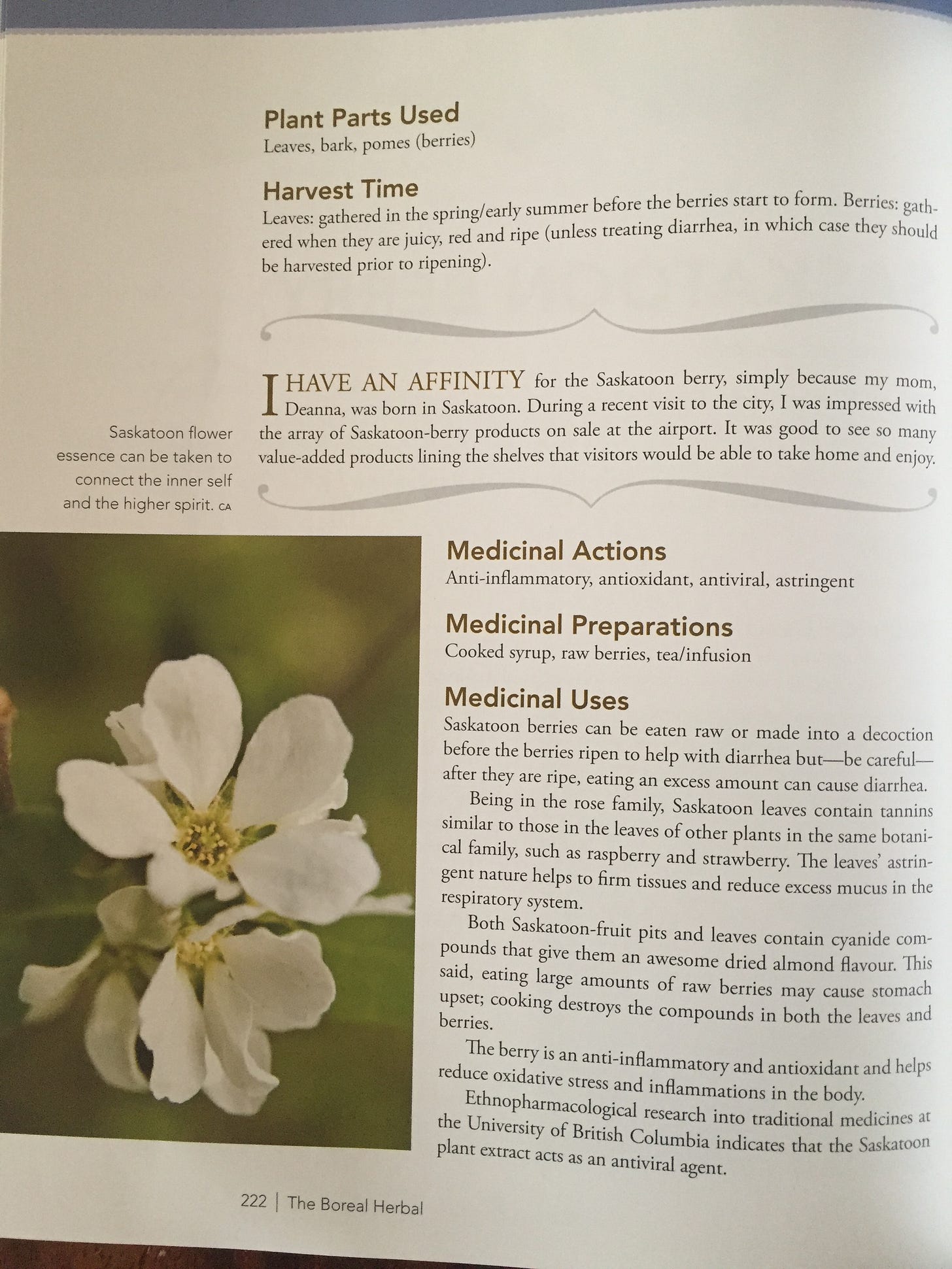

Service is an excellent tasting fruit similar to blueberry, with small edible almond-flavored seeds. The fruit is best picked when transitioning from red to purple. Research has shown the Juneberry contains more antioxidants than blueberries, strawberries, and raspberries.

Medicinal actions: anticarcinogenic, anti-inflammatory, antidiabetic, vessel-protecting, neuroprotective, Tonic, analgesic, Eye Medicine, bitter, cholagogue, mild, Gastrointestinal Aid, Anthelmintic, Astringent hydrating, Pediatric Aid, Cough Medicine, detoxifying, Pulmonary Aid, Appetizer, Birthing aid, Diaphoretic, Febrifuge, Ophthalmic, Stomachic and rich in plant nutrients.

Pharmacology:

Flavonoids protect DNA

Antioxidants (Anthocyanins) offer anti-inflammatory, immune system optimizing and anti-cancer actions.

Amygdalin initiates apoptosis in a range of different types of cancer cells.

Cold Hardiness: 2 - 10

Native Range:

Serviceberries (Amelanchier) are a genus of plants containing multiple species of shrubs/small trees found throughout temperate regions of the world. Serviceberries are in the rose family, making them cousins to common edible plants like apples, pears, and plums.

Amelanchier is native to temperate regions of the Northern Hemisphere, growing primarily in early successional habitats. It is most diverse taxonomically in North America, especially in the northeastern United States and adjacent southeastern Canada, and at least one species is native to every U.S. state except Hawaii and to every Canadian province and territory. Two species also occur in Asia, and one in Europe.

The maps below show the native range of the three species I am most familiar with but keep in mind both of those species are capable of being grown in a much wider range than the maps shows.

GROWTH FORM:

Amelanchier arborea is a small tree or a large multi-stemmed shrub of rounded outline.

Some species can grow to 40 feet in height with a single stem and live up to 70 years.

REPRODUCTION:

Pollination is required for seeds in order to start the endosperm formation. Amelanchier Canadensis have both male and female organs present in its flowers, meaning that the organism is hermaphroditic. Pollination occurs when bees or other small insects land on the flower and drink the plants nectar.

Habitat and Ecological Niche:

The serviceberry has a medium growth rate, which means they grow between 13-24 in per year. They are considered to be a small forest tree or perennial shrub, since it has several stems. The trees can be found throughout Canada and the United States. The serviceberry shrub can be found at the edge of forests, field and woodlands, and prefers partial sunny to partial shady sites. They are able to grow in moist, acidic and rich soils, but are easily adaptable to dry soils.

Service Berry In The Boreal Forest

Service berry is often found as a large shrub or small tree, appearing anywhere from about 6 feet tall to up to 25-40 feet in height with a trunk no larger than 6-12″ in diameter. According to Linda Kershaw in Trees of Michigan, while it is easy to identify the Juneberry species, identifying the specific subspecies can prove very difficult or impossible due to hybridization (I’ve found this to be the case as well!). In fact, some scientists aren’t clear if Juneberry is one species or 20! Because of this, I am going to discuss the Juneberry/serviceberry species as a whole, with special attention to those that are common on Turtle Island (aka North America). Two places you will find Service berry are as taller understory trees in forests throughout its range as well as urban cultivars in housing developments, on campuses and in parks.

The serviceberry can grow in a number of different conditions, with the exception of very wet areas or wetlands. It prefers drier soil, and so you are more likely to find it higher ground/uplands, etc.

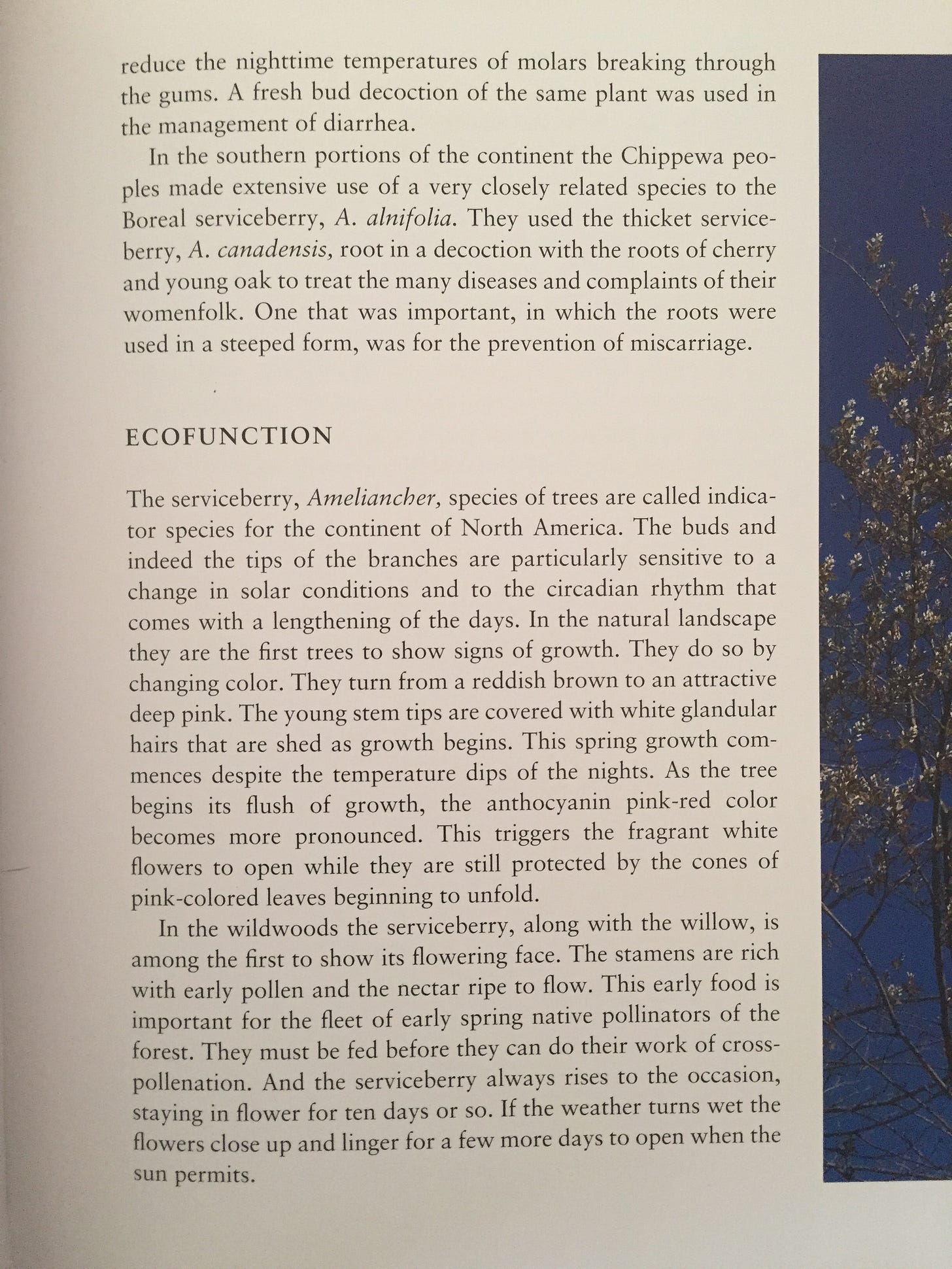

The flowers here often come out before leaves are on any of the trees (another characteristic of the understory trees–they take advantage before the overstory covers everything up).

Flowering and Pollination

The serviceberry has a lifespan of about 60 years over which it has a four-season appeal. It usually flowers in the spring, bears fruit during the summer, has a beautiful fall foliage (orange and red), and has a ziz-zag pattern of twigs in the winter. In the spring, the plant begins its annual growth cycle, as small white flowers begin to appear from the pinkish colored bud. The flowers appear before any green leaves are mature. Serviceberry is one of the first shrubs to flower and can be found in clusters. After the blooms fade away, the fruits begin to appear in early summer (late in June). These fruits are sweet juicy and are red-purple in color. The actual size of these fruits is 15mm in diameter, with 2-5 small seeds at the core. The flowering of serviceberry provides pollen for bees in the early spring.

Although they’re called “berries,” serviceberries actually produce a pome fruit, botanically akin to apples and pears.

Additional Facts about the Serviceberry

Berries look similar to blueberries, but are not related. You can use them in the same way as blueberries; pies, preserves and juices. They are also rich in antioxidants!

Most plants are shrubby, but a few varieties are more like trees

Provide dense cover for birds and delicious berries!

Provide food and shelter for other wildlife!

Beautiful white flowers in/around June

Berries grow in mid-summer

Brilliant red/orange leaves in the fall, before they drop (it’s a deciduous tree/shrub)

From 6-30 feet tall, but can be pruned to maintain a smaller size

Excellent edible living fence/windbreak

Safe for planting near power lines, average height of plant doesn’t exceed 25-30 feet!

Health Benefits of Serviceberries:

They been being used by the indigenous peoples of Turtle Island for ages as a food for purifying and giving strength.

They have potential preventative and therapeutic effects on many diseases such as cancers, inflammation and cardiovascular diseases, obesity, neurodegenerative pathologies, and muscular degeneration [6, 11, 14]. Because Saskatoon berries have high levels of beneficial flavonoids, such as anthocyanin, flavonol, and proanthocyanidin [3, 14, 21], research into its antioxidant, anti-inflammatory, antitumor, and antidiabetic properties have become a hot spot in recent years. Studies found that the total anthocyanin content significantly correlated to its antioxidant properties.

Anti-inflammatory – due to high anthocyanins and proanthocyanidins

Protection against cardiovascular and chronic inflammatory diseases – because the phenolic compounds reduce the oxidative stress mediated by nitric oxides.

Potential anti-diabetic – Saskatoon berries strongly inhibited an enzyme involved in the etiology of diabetic microvascular complications

Potential in anti-cancer therapy for esophageal, colon, skin and lung cancer

Antioxidants:

Service/Saskatoon berries contain twice the antioxidant level of blueberries

Because Saskatoon berries have strong activities of free-radical scavenging, they have antioxidant properties [10]. A study found that concentrated crude extract of Saskatoon berries inhibited nitric oxide production in activated macrophages, showing a potential protective role against chronic inflammation [7]. Cyclooxygenase (COX, including COX-1 and COX-2) is an enzyme that helps form prostanoids, such as thromboxane, prostaglandins, and prostacyclins, from arachidonic acid. Inhibiting COX with drugs can alleviate symptoms such as inflammation, blood clotting, and pain. Previous studies found that anthocyanin (100 ppm) mixtures inhibit COX-1 and COX-2 [4]. The findings suggest that the polyphenolic compounds contained in extracts of Saskatoon berries can effectively protect biological membranes, increase the resistance of low-density lipoprotein (LDL) to oxidation, influence lipid metabolism, and inhibit DNA damage [13, 15].

Thanks to the great amount of different antioxidants serviceberries contain they have the ability to regulate blood pressure, help to prevent DNA damage caused by oxidant radicals and slow the aging processes. Furthermore, the action of the high amount of polyphenols and flavonoids combined in the serviceberries help to prevent a lot of cardiovascular diseases, strokes and even cancer.

Anti-inflammatory:

Bioactive anthocyanins found in the fruits of Amelanchier include cyanidin 3-galactoside 155 mg/100 g, cyanidin 3-glucoside 54 mg/100 g and cyanidin. (Adhikari et al. 2005). At 100 ppm, the anthocyanin mixture inhibited cyclo-oxygenase (COX)-1 and COX-2 enzymes at 66 and 67% respectively. Anthocyanins 1 and 2 and cyanidin inhibited COX-1 enzyme 50.5, 45.62 and 96.36%, respectively, at 100 ppm, whereas COX-2 inhibition was the highest for cyanidin at 75%. Cyclo-oxygenase enzymes are involved in mechanisms of pain and inflammation.

Antiviral Activity:

Methanolic extract A. alnifolia plant was found to be active at non-toxic concentration against enteric coronavirus (McCutcheon et al. 1995).

Natural painkiller:

Also, thanks to vitamin C and an enzyme which ihnibits the cyclo-oxygenase (which causes inflammation and pain) we can use these fresh berries as natural painkillers.

Antidiabetic Activity

Burns Kraft et al. (2008) found that nonpolar constituents including carotenoids, from 4 wild berry species including Saskatoon berries, were potent inhibitors of aldose reductase (an enzyme involved in the etiology of diabetic microvascular complications), whereas the polar constituents, mainly phenolic acids, anthocyanins, and proanthocyanidins, were hypoglycemic agents and strong inhibitors of IL-1b and COX-2 gene expression. Berry samples also exhibited the ability to regulate lipid metabolism and energy expenditure in a manner consistent with improving metabolic syndrome. The results demonstrated that berries like Saskatoon traditionally consumed by tribal cultures contained a rich array of phytochemicals with the capacity to promote health and protect against chronic diseases, such as diabetes.

Nutrient Dense:

Saskatoon berries contain abundant amounts of minerals, such as calcium, copper, iron, magnesium, manganese, and potassium, as well as vitamins (ascorbic acid, folic acid, pantothenic acid, pyridoxine, riboflavin, thiamin, and tocopherols) and fiber [3, 6, 13, 14]. Besides micronutrients, mature Saskatoon berries contain significant levels of the anthocyanins, flavonol, and proanthocyanidin classes of flavonoids [3, 14, 21]. The major type of anthocyanins in Saskatoon berries are cyanidin-based anthocyanins, which comprised 63% of all phenols and 94% of anthocyanins in Saskatoon berry [6, 19]. The content of anthocyanins is often low in young fruits and dramatically increases from stage 5 to 9 of the nine-stage maturation of fruits [4, 14].

Tons of vitamins, minerals and fiber for your diet Serviceberries contain lots of vitamins A & C as a great antioxidants. Vitamin K for blood clotting, Vitamin E for sexual health and good skin, B Vitamins for good mood and vitality, iron for anemia, calcium for strong bones, fiber for colon health promoting probiotic bacteria… and magnesium and manganese for enzyme production and immunity.

Not only do the fruits of the Saskatoon berry plant contain high contents of multiple phenolic compounds, such as anthocyanins, quercetin, and proanthocyanidin, but also the leaves, stems, and roots of the plant also contain high levels of phenolic compounds. The composition of phenolic compounds in other parts of the Saskatoon berry plant is different from that in fruits. For example, the main phenolic components in the leaves of the Saskatoon berry were quercetin 3-galactoside, chlorogenic acid, and (−)-epicatechin; the main compounds in the stem included flavonol and flavanone glycosides, catechins, and hydroxybenzoic acids [6, 7].

Positive Impact on the Gut Microbiome:

The gut microbiome plays an important role in the development of obesity, diabetes, and chronic inflammation. Zhao et al. investigated the effects of Saskatoon berry powder on gut microbiota. The findings suggest that the administration of 5% Saskatoon berry powder improves the profile of gut microbiota by a relative increase in the abundances of good bacteria, which possibly contributes to its hypoglycemic and hypolipidemic effects in mice.

Optimizing The Innate Immune System:

Saskatoons contain high levels of antioxidants thought to act as a protective guard to our immune system.

Labratory tests have shown that Saskatoon berries and products contain high ORAC values (Oxygen Radical Absorbance Capacity – a test that quantifies the total antioxidant capacity)

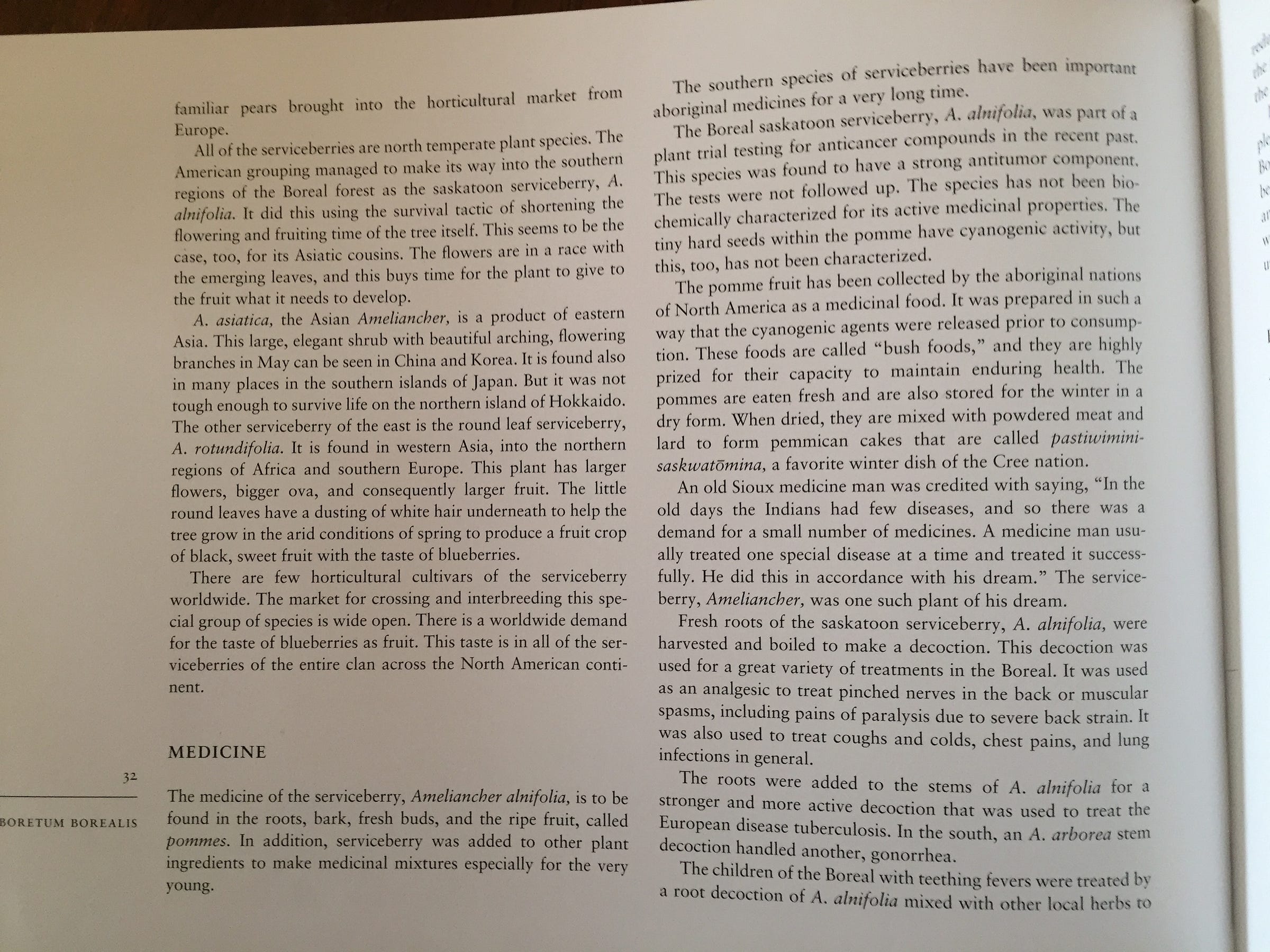

Traditional Medicinal Uses

Indigenous people in Canada used to juice for treating stomach ailments and as a laxative. Eye and ear-drops were made from ripe berries. The boiled bark is used as a disinfectant. The root infusion was used to prevent miscarriage after an injury. Thompson people made a tea from the twigs and stem and administer it to women just after birth and as a bath. A potent tonic from the bark was given to women after delivery to hasten discharge of the placenta (Turner et al. 1990) Saskatoon berry juice was ingested to relieve stomach upset and boiled berry juice was used as ear drops (Kershaw 2000).

Anti-Cancer Potential of the Seeds:

Many studies have also suggested that C3G (found in Service Berries) may help with reproductive pathway issues and reducing tumors. Li et al. reported that C3G can be protective against cadmium- (Cd-) induced male reproductive dysfunction through regulating the hypothalamus-pituitary-gonadal (HPG) axis in male mice during puberty. C3G increased Gnrh1 gene expression in the hypothalamus, reversed the levels of gonadotropins (such as luteinizing hormone (LH) and follicle-stimulating hormone (FSH)), and improved the expression of LH and FSH receptor in the testis in mice exposed [30]. A key mechanism underlying tumor progression is angiogenesis. Studies found that C3G inhibited breast cancer-induced angiogenesis via attenuating the signal transducer and activator of the transcription 3 (STAT3)/VEGF pathway [31]. Harada et al. also evaluated the role of D3G on lipid accumulation induced by senescence in HepG2 (a human cell line derived from hepatocyte carcinoma). They found that D3G inhibited palmitic acid- (PA-) induced lipid accumulation and cellular senescence and reversed the expression of SMARCD1 to the level of the untreated hepatocytes [32]. Future studies will assess the variety of roles that anthocyanins play in biological pathways.

Serviceberry seeds are also a source for a natural substance that kills some types of cancer cells without destroying the healthy cells. The essential ingredient has been called amygdalin, laetrile or vitamin B 17.

If there is any merit to it, why is this information being suppressed?

Keep in mind that the cancer industry world wide is estimated at a 350 billion dollar a year industry. There are many in various associated positions within that industry who would be without a job if that cash flow dried up suddenly with the news that there are cheaper, less harmful, and more efficacious remedies available.

What is B17, or Laetrile Anyway?

In 1952, a biochemist named Dr. Ernst Krebb, Jr. in San Francisco decided that cancer was a metabolic reaction to a poor diet, and a missing nutrient from modern man's diet could be the key to overcoming cancer. His research led to a compound found in over 1200 edible plants throughout nature. That compound is amygdalin.

Amygdalin is found with the highest concentration and necessary enzymes in apricot seed kernels. A primitive tribe, the Hunzas, were known to consume large amounts of apricot seed kernels. The hard pit had to be broken to get into the soft kernels. There was no incidence of cancer with them at all, ever. And they had long, healthy life spans. Laetrile was created by simply extracting amygdalin from the soft apricot kernels, purifying it and putting it into a concentrated form.

(For more info on the Hunza people, click Here or Here)

Amygdalin is a nitrioloside. Nitriolisides are difficult to categorize since they are in foods but not foods themselves. As a nitrioloside, amygdalin resembled the B complex structures, so Dr. Krebb called it B17 since by that time 16 types of B vitamins had been isolated.

So How Does It Work?

Amygdalin contains four substances. Two are glucose; one is benzaldyhide, and one is cyanide. Yes, cyanide and benzaldyhide are poisons if they are released or freed as pure molecules and not bound within other molecular formations. Many foods containing cyanide are safe because the cyanide remains bound and locked as part of another molecule and therefore cannot cause harm.

There is even an enzyme in normal cells to catch any free cyanide molecules and to render them harmless by combining them with sulfur. That enzyme is rhodanese, which catalyzes the reaction and binds any free cyanide to sulfur. By binding the cyanide to sulfur, it is converted to a cyanate which is a neutral substance. Then it is easily passed through the urine with no harm to the normal cells.

But cancer cells are not normal. They contain an enzyme that other cells do not share, beta-glucosidase. This enzyme, virtually exclusive to cancer cells, is considered the "unlocking enzyme" for amygdalin molecules. It releases both the benzaldyhide and the cyanide, creating a toxic synergy beyond their uncombined sum. This is what the cancer cell's beta-glucosidase enzyme does to self destruct cancer cells.

Amygdalin or laetrile in conjunction with the protective enzymes in healthy cells and the unlocking enzymes in cancer cells is thus able to destroy cancer cells without jeopardizing healthy cells. Chemotherapy, on the other hand, kills a lot of other cells and diminishes one's immune system while killing an undetermined amount of cancer cells.

Well the good news is if you cannot grow apricots where you are there is a good chance you can grow Service berries and mature (purple) service berries contain amygdalin too! One study found 42–118 mg/kg of Amygdalin of fresh weight berries.

References:

History and Cultural Relevance of Service Berries

In Edible Wild Plants of Eastern North America, Rollins notes that Juneberry was well esteemed by both early European explorers and Native American tribes. Native Americans would gather the berries, beat them into a paste, and dry them into cakes. The dried berries were then mixed with cornmeal and used in old-style puddings. Further, John Eastman notes that the berries were one of the primary fruits included in traditional pemmican–a mixture of dried meat (often venison or bear), fat, and berries that offer high calories and fat. In Medicinal and Other Uses of North American Plants by Charlotte Erichsen-Brown, a range of indigenous uses of the berries are described, including how the Iroquois would ferment dried Juneberry, sugar, and water to make a refreshing drink (noted in 1916). The Chippewa found them so refreshing that the term “Take some Juneberries with you” was a common expression to be told to relax. Many tribes dried the Juneberry for eating in the winter months and used it for various winter food applications.

It is said that the Amelanchier alnifolia or serviceberry was the most important fruit of indigenous peoples in Idaho. They ate the sweet berries fresh from the trees, and picked large quantities of them to dry for use throughout the year. Resembling raisins in appearance when dried individually, they were used to flavor stews, puddings and vegetable dishes. They were mashed and formed into cakes or thin sheets and used as treats.

The Shoshone are said to have made a bread of sunflower seeds, lambs quarter and serviceberries. Cree people routinely used the berries in their Pemmican to cut the fatty taste. The Cree word for the dark purple berries is mi-sakwato-min, or "tree of many branches berries."

The wood of the Juneberry is very heavy, hard, strong, and close-grained. It has a dark red-brown appearance with lighter colored sapwood. Today, it is a favorite wood of spoon carvers and, in larger pieces, it is good for wood turning. Erichsen-Brown notes that the wood was used to make arrow shafts and pipe stems by indigenous peoples, particularly because it was so hard.

Eastman notes that the Juneberry has traditionally been used as a seasonal clock widely in North America, and he indicates that no other tree has quite this feature. In Colonial times, the blooming of the Juneberry was used by fishers to know when the spawning of shad fish happened (hence the common name “shadbush” given to the tree).

Erichsen-Brown notes that the roots and bark were traditionally used by some tribes as medicinal tonics. Medicinally, Erichsen-brown notes a number of uses being tied to women’s health, particularly surrounding pregnancy. The Chippewa combined the bark of Juneberry was combined with that of pin cherry, chokecherry, and wild cherry decocted and drank for feminine issues. She notes that the Ojibwe used the bark also for an expecting mother, while the Iroquois used the fruit to treat post-childbirth pain and hemorrhage. I haven’t been able to find much in discussion of Juneberry in modern herbals, but it is clear from Erichsen-Brown’s work that this tree is traditionally connected with women’s health. Plants for a Future lists a few additional uses, including being used in the treatment of snow blindness, use for a spring tonic, and astringent qualities. Since Juneberry is in the rose family, these last two certainly fit!

For some additional cultural context on this species, check out this excerpt from “The Serviceberry : Abundance and Reciprocity in the Natural World” By Robin Wall Kimmerer.

Serviceberry Functions In The Wilderness and in the Food Forest:

Ecological Functions

In ecosystems serviceberries provides food for over 30 species of birds (including pheasant, grouse, mockingbirds, northern flicker, blue jay, American crow, cardinals, cedar waxwings, towhees, American redstart, gray catbird, American robin, varieties of thrush, Baltimore orioles, and many others). Birds love them when they are fattening up for their fall migration. The spring pollen and nectar are an important source for bees and other insects., as well as animals such as squirrels, fox and deer. Their large canopy creates a micro-climate for many smaller trees to reside. It also serves as a windbreak for other plants. This tree attracts many species of life, it also allows for the cycling of nutrients. The plant prefers shady sites at the edge of field and woodlands, as well as on the rocky slopes and riverbanks. Serviceberry can usually be found in the wild, as it is require little or no care.

I think it would be amazing to design a food forest guild that incorporated trees like Birch, White Pine and Ginkgo with an understory of Service Berry shrubs growing along side Goji Berries and other medicinal shrubs.

Guild Profile

A guild is a functional community of plants that is centered on a central element. These plants act in relation to the central element, and support the health, management, and act as an environmental buffer. For example, a functional community of plants for a climate in Canada or the Northern US could consist of:

Alder

Red Mulberry

Persimmon

Gooseberry

Comfrey

Stinging Nettle

Nasturtiums

Borage

Hairy Vetch

Saskatoon serviceberry

Traditional Medicinal Uses

The native people of the land have long used the Serviceberry plant. The tree bark is used to cure stomach troubles, and the twigs are used to make tea to recover patients after childbirth. The extraction of the fruit juice from the plant roots is used in the treatment of colds, chest pains and fevers.

Practical Uses

The tough wood proved to be an excellent material for making arrows, for digging sticks, spear shafts and handles for tools. Young stems are used to make rims, handles and baskets. These plants can also be used as windbreaks. The Saskatoon berries are used in making pies and various types of jellies.

Other Uses

Plants have a spreading, suckering root system and are used in windbreaks for erosion control. Young branches can be twisted to make a rope[257]. Wood - hard, straight grained, tough. Used for tool handles etc. The wood can be made even harder by heating it over a fire and it is easily moulded whilst still hot[99]. The young stems are used to make rims, handles and as a stiffening in basket making[257]. Landscape Uses: Erosion control, Massing, Woodland garden.

Role in Nature

The serviceberry plays an important role in the food web. Their large canopy (15ft) is home to many other birds, and serves as an important food source for birds, as berries are picked of the tree by birds over 30 species. Their twigs provide food for the snowshoe hare and red fox during cold winter months. The spring pollen and nectar are an important source for bees and other insects.

Seed Propagation

Serviceberries are easily propagated by seed. Ripe berries should be collected during July and August. Berries can be crushed and sieved out to get the seeds. The seed is best harvested (green), when the seed is fully formed, before the seed coat has hardened, they can be planted in pots outdoors.

Akiva Silver of Twisted Tree Farm has said that “the seeds from (serviceberries) germinate best when they are never allowed to dry out. Unfortunately, almost every source only sells dried seed. So, I'm feeling good about what I'm offering this year. Haskaps, Goumis, and Juneberry (aka Serviceberry) all packed in damp sand immediately after cleaning fruit. Seed packs are available www.twisted-tree.net

Lets get busy planting....berries everywhere is our future”

Seeds can be sown in the fall and should germinate next spring. Seeds could take as long as 18 months to germinate. Once the seeds germinate they can be grown in a garden for two years until a permanent spot is found for them. Seeds can be planted at 3 seeds per inch. Germination is usually less than 50%, but growth is rapid (1 ft per year). Root or cuttings may also propagate the plant, however there are not as successful as seed propagation.

Cultivation details

Landscape Uses: Specimen, Street tree, Woodland garden. Prefers a rich loamy soil in a sunny position or semi-shade but thrives in any soil that is not too dry or water-logged. Grows well in heavy clay soils. All members of this genus have edible fruits and, whilst this is dry and uninteresting in some species, in many others it is sweet and juicy. Many of the species have potential for use in the garden as edible ornamentals. The main draw-back to this genus is that birds adore the fruit and will often completely strip a tree before it is fully ripe[K]. The plant becomes dwarfed when growing in sterile (poor and acid) ground[227]. Hybridises with A. bartramiana, A. canadensis, A. humilis and A. laevis. Grafting onto seedlings of A. lamarckii or Sorbus aucuparia is sometimes practiced in order to avoid the potential problem of hybridizing[1].

Special Features:

Attracts birds, North American native, Attracts butterflies, Blooms are very showy. The plant is heat tolerant in zones 9 through 4. (Plant Hardiness Zones show how well plants withstand cold winter temperatures. Plant Heat Zones show when plants would start suffering from the heat. The Plant Heat Zone map is based on the number of "heat days" experienced in a given area where the temperature climbs to over 86 degrees F (30°C). At this temperature, many plants begin to suffer physiological damage. Heat Zones range from 1 (no heat days) to 12 (210 or more heat days). For example Heat Zone. 11-1 indicates that the plant is heat tolerant in zones 11 through 1.) For polyculture design as well as the above-ground architecture (form - tree, shrub etc. and size shown above) information on the habit and root pattern is also useful and given here if available. The plant growth habit is multistemmed with multiple stems from the crown

Amelanchier arborea

USDA hardiness: 3-8

Typical Habitats: Rich woods, thickets and slopes.

Common serviceberry or Downy Serviceberry, this species is present throughout the eastern half of the US and Canada.

Amelanchier arborea is a deciduous Tree growing to 10 m (32ft) by 12 m (39ft) at a slow rate.

It is typically in flower in April, and the berries ripen from June to July. The species is hermaphrodite (has both male and female organs) and is pollinated by Bees. The plant is self-fertile.

Suitable for: light (sandy), medium (loamy) and heavy (clay) soils and can grow in heavy clay soil. Suitable pH: mildly acid and neutral soils. It can grow in semi-shade (light woodland) or no shade. It prefers moist soil.

The trees have an extensive root system and can be planted on banks etc for erosion control. Wood - close-grained, hard, strong, tough and elastic. It is one of the heaviest woods in N. America, weighing 49lb per cubic foot. Too small for commercial interest, it is sometimes used for making handles or arrow shafts.

Berries are juicier than Saskatoon Service berries but have a shorter shelf life so are best enjoyed fresh, frozen or make into preserves after harvest.

Amelanchier alnifolia

The name Saskatoon originated from a Cree Nation noun (misâskwatômina).

USDA hardiness: 2-8

This is one of the smaller- growing members of the genus, forming a deciduous shrub that seldom exceeds 3 metres in height and occasionally suckering to form a slowly spreading clump.

An easily grown plant, it prefers a rich loamy soil and thrives in any soil that is not too dry or water-logged. The largest yields, and best quality fruits, are produced when the plant is grown in a sunny position, though it should also do reasonably well in semi-shade. The plants are fairly lime tolerant and they will also grow well in heavy clay soils. They are very cold-hardy and will tolerate temperatures down to at least -30°c and probably much lower.

Juneberries first make us aware of their presence in the garden in early to mid-spring when they come into flower. These white flowers are produced before the plants come into leaf, and are usually produced so abundantly that the whole plant turns white. They look particularly beautiful at this time. By late June, or more commonly early to mid July (depending on how far north you are), the plants will usually be carrying large crops of fruits. These fruits are about 15mm in diameter, they are soft, sweet, juicy and packed full of vitamins and anthocyanin. There are usually 2 - 5 seeds contained in an apple-like core at the centre of the fruit, these are small enough to be eaten without problems, though they can add a slightly bitter almond-like flavour to the fruit if they are crushed whilst eating. The fruit can also be cooked in pies etc., when dried it is quite sweet and can be used in the same ways as raisins.

Come the autumn, and the plant once more makes its presence felt in the garden as the leaves take on lovely yellow and red shades of autumn colour before falling.

Juneberries are very easy to propagate and seed is the simplest method if this can be obtained. It is best sown as soon as it is ripe in the summer, and should then germinate in late winter. Stored seed can be a bit slow to germinate - don't give up on it for at least 18 months. The main problem of growing from seed is that you can never be sure of the quality of your seedling plants. Juneberries are very promiscuous creatures and will readily cross-pollinate with other juneberry species growing nearby. Unless you want to experiment with producing superior fruiting forms, it is best either to obtain seed from a known wild source so that you can be fairly sure the seed will breed true, or to grow plants from suckers. Simply dig up 2 - 3 year old suckers in the winter and either pot them up or, if they are well-rooted, plant them straight out into their permanent positions. These plants should be exact copies of their parents and, whilst seedlings can take up to 5 years before they start to produce fruit, these suckers will generally start to produce within a couple of years.

Amelanchier alnifolia is available from a number of nurseries and garden centres. There are also a number of named varieties that have been developed in N. America for their improved fruiting qualities. These are not generally available in Britain, though we are hoping to obtain a number of them in the next few years. Watch this space for more information!

Another species of juneberry that we highly recommend is A. stolonifera. This is a bit larger than A. alnifolia, perhaps reaching 5 metres in height, and it also suckers much more freely to eventually form quite large clumps. The fruit is larger than A. alnifolia and, if anything, is even nicer flavoured. Another positive attribute is that it can start to fruit in its second year of growth and is giving very good crops by the time it is four years old. This species, unfortunately, is not currently available in Britain though we are busy propagating our plants and hope to be able to supply it within the next few years.

Service Berry Recipes

For the most part, any recipe that calls for blueberries can be made with serviceberries. The fruit has a more intense flavor, that’s a bit like a blueberry on steroids. It’s honestly hard to describe until you’ve tasted one, but I think they’re one of the very best tasting (if not the best tasting) wild berries.

If you’re lucky enough to have more than you can eat fresh, there are countless ways to make serviceberries into delicious foods and beverages such as:

sauces

pies, cobblers, muffins, and other baked goods

preserves

sweet or savory fermentations

drinks

Serviceberry recipes:

Serviceberry cobbler made in a cast iron pan

Crustless serviceberry custard pie

Saskatoon Serviceberry Wine

3-4 lbs Saskatoon berries

2 lbs granulated sugar

1 lb raisins (if desired)2 lemons (juice only)

1 tsp pectic enzyme

5 pints water

1 crushed Campden tablet

wine yeast and nutrient

There are two methods recommended in making this wine. No matter which one you choose, first you must gather the berries. Pick only ripe berries. Wash, de-stem and crush the berries.

Method 1: Put in primary with sugar, lemon juice, water, and crushed Campden tablet, stirring well to dissolve sugar. Cover with muslin and put in warm place. Add pectic enzyme after 12 hours and wine yeast and nutrient after additional 12 hours. Stir twice daily for 5 days. Strain through a medium-meshed nylon sieve, pressing lightly to extract juice, returning liquor to primary. Recover primary and wait 24 hours, then siphon off sediment into secondary and fit airlock, adjusting volume to allow 3 inches of space for foaming. Move to cooler place. When vigorous fermentation subsides (10-14 days), top up with water or reserved juice. Ferment additional 2 weeks, then rack into clean secondary. Refit airlock and rack after 30 days. Wait another 30 days, rack again and bottle. This is a very good dry wine, fit to taste after 6 months. Improves with additional aging. Two gallons of berries should make 5 gallons of wine.

Method 2: Heat to low boil, reduce heat, and simmer covered for 10 minutes. Fold top berries under, recover and simmer another 10 minutes. Pour into nylon jelly-bag and allow to drip over primary until pulp is cool. Meanwhile dissolve sugar into 3 cups boiling water and allow to cool. Add juice, jelly-bag, juice of 2 lemons, yeast nutrients, and pectic enzyme to primary. Wait at least 10 hours before inoculating with wine yeast. Cover well and set in warm (70-75 degrees F.) place, stirring twice daily. When S.G. drops to 1.040 (about 5 days), gently press jelly-bag to extract clear juice, discarding remaining pulp and seed. Siphon off sediments into secondary, top up, fit airlock, and set in cooler (60-65 degrees F.) place. Rack after 30 days and again after another 30 days. Bottle when clear, racking only if additional sediments have formed. Store in dark place to preserve deep ruby color. May taste after 6 months but improves with age. One and one-half gallons of berries should make 5 gallons of wine.

Serviceberry Jam

10 cups ripe serviceberries

1/2 cup water

3/4 cup sugar per cup of pulp

6 oz liquid pectin

Wash and stem berries, then place into a saucepan and crush. Add water and cook over medium heat for 5 to 6 minutes. Measure pulp and add sugar and return to pan. Place over low heat and cook for a few minutes more or till the sugar dissolves. Bring to a boil and add pectin, then hold boil for 1 full minute. Remove from heat, skim foam, and pour into hot, sterile jelly jars and seal.

Serviceberry Jelly

9 cups ripe serviceberries

3/4 cup of sugar per cup of juice

1/2 cup water

3 oz liquid pectin

Stem and wash berries. Place into saucepan and crush a few. Add water. Simmer fruit over low heat for about 10 to 15 minutes. Strain the cooked berries through a jelly bag and recover the juice. Measure juice and place in saucepan with sugar. Mix well and place over a high heat. Bring to a boil and add pectin. Return to boil and hold it for 1 full minute. Skim foam and pour into hot, sterile jelly jars and seal.

Gin Fizz with Serviceberry Syrup ~ Inspired by the Seasons

Fermented Serviceberry Syrup ~ Edible Ohio Valley

Serviceberry Muffins ~ Persephone’s Kitchen

Serviceberry Ice Cream ~ Explore Big Sky

Other recipe ideas:

In closing I will share part of an essay that speaks to the wisdom and abundant gifts that generous rooted beings such as the Service Berry share with humanity.

Robin Wall Kimmerer, the author of Braiding Sweetgrass, wrote a remarkable ode to Serviceberry for Emergence Magazine, titled “The Serviceberry: An Economy of Abundance.” Her words explore the ethic of reciprocity and taste like the sweet and tart flavor burst of Serviceberry herself:

“The cool breath of evening slips off the wooded hills, displacing the heat of the day, and with it come the birds, as eager for the cool as I am. They arrive in a flock of calls that sound like laughter, and I have to laugh back with the same delight. They are all around me, Cedar Waxwings and Catbirds and a flash of Bluebird iridescence. I have never felt such a kinship to my namesake, Robin, as in this moment when we are both stuffing our mouths with berries and chortling with happiness. The bushes are laden with fat clusters of red, blue, and wine purple, in every stage of ripeness, so many you can pick them by the handful. I’m glad I have a pail and wonder if the birds will be able to fly with their bellies as full as mine.

This abundance of berries feels like a pure gift from the land. I have not earned, paid for, nor labored for them. There is no mathematics of worthiness that reckons I deserve them in any way. And yet here they are—along with the sun and the air and the birds and the rain, gathering in the towers of cumulonimbi. You could call them natural resources or ecosystem services, but the Robins and I know them as gifts. We both sing gratitude with our mouths full.

Part of my delight comes from their unexpected presence. The local native Serviceberries, Amelanchier Arborea, have small, hard fruits, which tend toward dryness, and only once in a while is there a tree with sweet offerings. The bounty in my bucket is a western species—A. alnifolium, known as Saskatoons—planted by my farmer neighbor, and this is their first bearing year, which they do with an enthusiasm that matches my own.

Saskatoon, Juneberry, Shadbush, Shadblow, Sugarplum, Sarvis, Serviceberry—these are among the many names for Amelanchier. Ethnobotanists know that the more names a plant has, the greater its cultural importance. The tree is beloved for its fruits, for medicinal use, and for the early froth of flowers that whiten woodland edges at the first hint of spring.

Gratitude and Reciprocity are the currency of a gift economy, and they have the remarkable property of multiplying with every exchange. Their energy concentrating as they pass from hand to hand. A truly renewable resource.

Continued fealty to economies based on competition for manufactured scarcity, rather than cooperation around natural abundance, is now causing us to face the danger of producing real scarcity, evident in growing shortages of food and clean water, breathable air, and fertile soil.

Crop failures and Erratic weather is a product of this extractive economy and is forcing us to confront the inevitable outcome of our consumptive lifestyle, genuine scarcity for which the market has no remedy. Indigenous story traditions are full of these cautionary teachings. When the gift is dishonored, the outcome is always material as well as spiritual. Disrespect the water and the springs dry up. Waste the corn and the garden grows barren. Regenerative economies which cherish and reciprocate the gift are the only path forward. To replenish the possibility of mutual flourishing, for birds and berries and people, we need an economy that shares the gifts of the Earth, following the lead of our oldest teachers, the plants...

As I forage for service berries, I accept that gift from the bush, and then spread that gift with a dish of berries to the neighbor, who makes a pie to share with his friend (who feels to wealthy in food and friendship, that he volunteers at the food pantry) you know how it goes. To name the world in gift, is to feel one’s membership in the web of reciprocity. It makes you happy and it makes you accountable. Conceiving of something as a gift changes your relationship to it in a profound way. Even though the physical make up of the ‘thing’ has not changed.

A wooly knit hat purchased at the store will keep you warm regardless of it’s origin, But it it was hand knit by your favorite auntie, then you are in relationship to that ‘thing’ in a very different way. Your responsible for it, and your gratitude has motive force in the world. You are likely to take much better care of the gift hat, than the commodity hat, because it’s knit of relationships. This is the power of gift thinking.

I imagine that if we acknowledge that everything we consume is the gift of Mother Earth, we would take better care of what we are given. Mistreating a gift has emotional and ethical gravity, as well as ecological resonance. How we think, ripples out to how we behave. If we view these berries, or that coal, or that forest, as property, it can be exploited as a commodity in a market economy. We know the consequences of that. Why then, have we permitted the dominance of economic systems that commodify everything? That create scarcity instead of abundance. That promote accumulation rather than sharing. We’ve surrendered our values to an economic system that actively harms what we love."

– Robin Wall Kimmerer

https://emergencemagazine.org/story/the-serviceberry/

Additional info on Service berry:

https://shadesofgreenpermaculture.com/blog/conscious-business/in-celebration-of-serviceberry/

Serviceberry Tree

Hawthorn and Serviceberry/Shadbush/Saskatoon hedge

use of serviceberry wood

Saskatoon berry monoculture to permaculture conversion possible?

Strawberry, Saskatoon, Bush Cherry project

Disease on Juneberry

https://practicalselfreliance.com/serviceberries-amelanchier/

https://practicalplants.org/wiki/amelanchier_canadensis/

https://practicalplants.org/wiki/amelanchier_lamarckii/

https://pfaf.org/user/plant.aspx?LatinName=Amelanchier+alnifolia

https://pfaf.org/user/cmspage.aspx?pageid=53

https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC7126499/

The above post was the third installment of a series titled Stacking Functions in the Garden, Food Forest and Medicine Cabinet : The Regenerative Way From Seed To Apothecary.

Stacking Functions in the Garden, Food Forest and Medicine Cabinet : The Regenerative Way From Seed To Apothecary

Hello everyone! I am announcing a new series which will eventually get compiled and formatted into my next book. Recipes For Reciprocity: The Regenerative Way From Seed To Table is a book that I wrote to offer techniques, perspectives and recipes that invite …

The above post was also constituted the 5th installment of the Befriending The Boreal series.

Befriending The Boreal - An Honest Look At The Potential Ecological/Cultural Impacts Of The Large Scale Open Pit Lithium Mines Planned For Northern Canada

This post offers an introduction to a series I will be publishing with the intent of inviting people to get to know the Boreal Forest and it's many inhabitants to hopefully come to see these beings with love, respect and a feeling of kinship. I wish that the impetus for this series was simply my want to introduce people to a truly magical, healing and sp…

I just planted one of these (a bareroot slip) this past fall in a newly cleared area in the southeast of my yard. Surrounded by welded wire for protection against deer. Got it from a local "permaculture" grower, uncertain of the variety. He basically propogates what seems to do well here and offers them. (edibleacres.org)

I was first made aware of the delectability of the fruit when "grazing" upon several trees growing in a commercial area nearby in occupied Haudonsanee land. Delicious!

I had considered blueberries but they require highly acid soil prep and these do not.

I also grew a Saskatoon in the drought stricken caliche in 5000 foot altitude New Mexico and it did pretty well even with minimal supplemental irrigation.

Thanks for the info Gavin!

Serviceberry, jubeberry, shadbush, saskatoon and about a dozen other names — or, as the saying goes, «a beloved child has many names».

On this (European) side of the pond, it has escaped into wild in many areas and could theoretically be considered an invasive species — but, strangely enough, I can't recall anyone ever raising any objections to it. (Well, except perhaps mothers whose kids come home in stained clothes.)