Shagbark and Shellbark Hickory (Carya ovata and Carya laciniosa)

Exploring the many gifts offered by Shagbark/Shellbark Hickory in the context of Food Forest Design. Installment #17 of the Stacking Functions in the Garden, Food Forest and Medicine Cabinet series.

This post serves as the 17th post which is both part of the above mentioned (Stacking Functions in the Garden, Food Forest and Medicine Cabinet : The Regenerative Way From Seed To Apothecary series).

The Shagbark Hickory (Carya ovata) is a large deciduous tree native to the eastern United States and Canada. Also known as the Scalybark Hickory or the Upland Hickory, it’s a long-lived perennial that may reach 350 years old or more.

Shagbark hickory trees are an incredible find in non-tended (wild) forests and a powerful ally to work with when designing a food forest. These long-lived trees produce some of the sweetest wild nuts you can taste anywhere. More than just for nuts, the bark is also edible and used to infuse a vanilla/butterscotch flavor into meals.

Their distinctive bark will give them away, young or old, and it comes off in sheets that have been used to flavor meals (meat and sweets alike) for millennia.

Common Name: known as "Mitigwaabaak" to the Potawatomi people long before the English language assigned a name to the tree. Also known as the Shagbark Hickory, Scalybark Hickory or the Upland Hickory.

Shellbark Hickory (the bigger cousin of Shagbark) is also known as the Kingnut (or “mtegwabak” in the Potawatomi language).

The word hickory is derived from the Algonquian word, “pawcohiccora”, describing an oily nut milk made from pounding hickory nut kernels that had been boiled. This sweet nut milk was used by the Creek in their hominy and corn cakes.

Family: Juglandaceae

Part used for medicine/food:

Nuts/Seeds - filled with nutrient dense nutmeat that has an extremely long shelve life. Can be eaten raw or cooked and used in pies, cakes, bread etc. Sweet and delicious. The seed can be ground into a meal and used to thicken soups etc. A nut milk can be prepared from the seed and this is used as a butter on bread, vegetables etc. Oil can be pressed from the nuts and used instead of olive oil.

Bark: The bark can be used to treat a variety of ailments, both internally and externally:

Poultice: The bark can be used as a poultice to treat arthritis.

Tea: The inner bark can be used as a tea to treat indigestion, coughs, throat irritation, and fevers.

Wash: The boiled bark can be used to treat and clean abrasions, burns, rashes, and other topical skin irritations.

Powder: The bark can be used to create a powder that can be combined with other tree parts or plants for heart medicine.

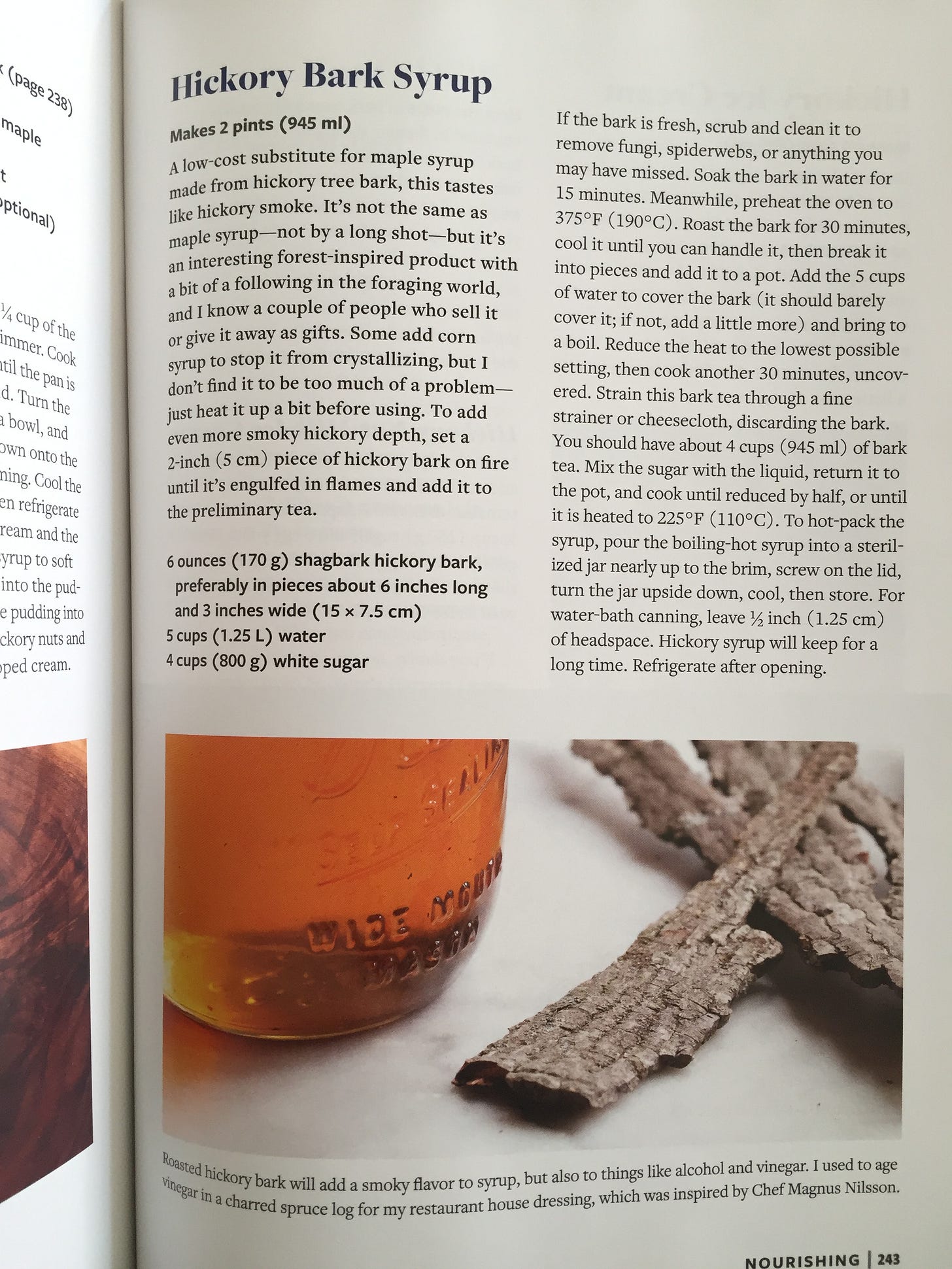

Syrup: The bark can be made into a sweet syrup.

Young shoots: The young shoots can be steamed and inhaled to treat convulsions and headaches.

Constituents:

Hickory nuts are brimming with vitamins, minerals, protein, fiber, and good carbohydrates. The nuts are full of vitamin A, vitamin C, Vitamin B-6, vitamin B-1, and fatty acids.

Protein

Hickory nuts are a rich source of plant protein, which is essential for muscle and bone growth and development.

Minerals

Hickory nuts are a great source of minerals, especially calcium, magnesium, phosphorous, and potassium.

Folate

Hickory nuts are a good source of folate, which is important for expectant mothers.

The syrup made from the bark or sap of the tree is also mineral rich and provides a localized source of sugar (varying blends of sucrose, fructose and glucose, which are the same sugars found in maple syrup.)

Hickory bark is one of the highest plant sources of magnesium. Magnesium plays a role in many bodily functions including neurotransmission and muscle contraction, and is important for healthy heart function and in combating muscle pain and fatigue.

Medicinal actions:

Nutritive, Analgesic, Antirheumatic, Cardiac tonic, anti-inflammatory, diaphoretic, digestive, diuretic and as a purgative.

Cold Hardiness:

Carya ovata (Shagbark) 4-8

Carya laciniosa (Shellbark aka Kingnut) 4-9

Native Range (and naturalized range) and habitat:

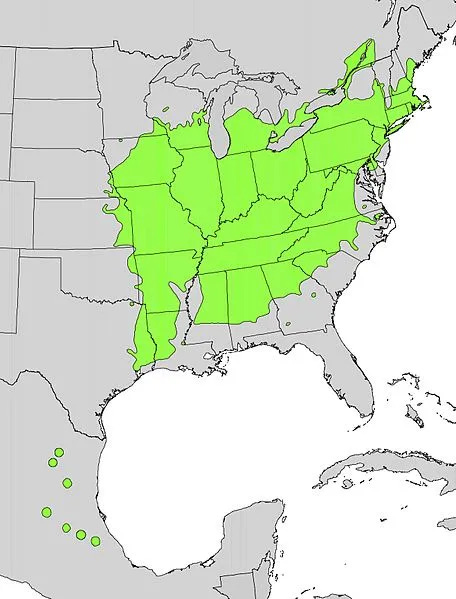

Carya ovata:

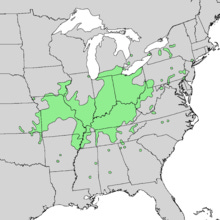

Carya laciniosa:

The native range of Carya ovata is most of eastern Turtle Island (aka North America) with a few exceptions:

Eastern United States: From southeastern Nebraska and Minnesota, east through southern Ontario and Quebec, to Maine, and south to Georgia, Alabama, Mississippi, Louisiana, and eastern Texas

Eastern Canada: An isolated population grows as far north as Lavant Township

Northeastern Mexico: Disjunct populations grow in the mountains

Europe: Introduced in the 17th century, it can still be found in Central Europe as a non-native species

The native range of Carya laciniosa, also known as shellbark hickory, is from New York to Tennessee and Oklahoma, and from southern Ontario to southeastern Nebraska. It's most common in the Ohio and upper Mississippi River valleys.

Range

New York: Western New York and the Hudson Valley

Michigan: Southern Michigan

Iowa: Southeast Iowa

Kansas: Eastern Kansas

Oklahoma: Northern Oklahoma

Tennessee: Tennessee

Pennsylvania: Pennsylvania

Missouri: Central Missouri

Arkansas: Central Arkansas

Ontario: Southern Ontario

Habitat

Deep, fertile, moist soils

Heavy loams or silt loams

Neutral or slightly alkaline soils

Flood plains and valleys

Along stream banks

The morphology of Carya laciniosa is highly variable and like with wild apples, such phenotypic instability might suggest frequent hybridizations between translocated populations dispersed by indigenous people.

Climate

Shagbark hickory grows best in a humid climate. It is one of the hardiest of the hickory species, however, and has successfully adapted to a wide range of climatic conditions. Within shagbark's natural range, average annual rainfall varies from 760 to 2030 mm (30 to 80 in) with 510 to 1020 mm (20 to 40 in) of rainfall during the growing season. Average snowfall usually is less than 3 cm (1 in) in the southern and southwestern portion of the tree's range to 254 cm (100 in) or more in northern New York and southern Ontario.

Within the range of shagbark hickory average annual temperatures vary from 4° C (40° F) in the north to nearly 21° C (70° F) in southeastern Texas. Average January temperature varies from -9° to 13° C (15° to 55° F) while mean July temperature varies from 18° to 27° C (65° to 80° F). Extreme temperatures of -40° and 46° C (-40° and 115° F) have been recorded within shagbark's natural range. The average growing season also varies widely from about 140 days in the North to 260 days in the South.

Soils and Topography

Sites occupied by shagbark hickory vary greatly. In the North it is found on upland (often south-facing) slopes, while farther south it is more prevalent on soils of alluvial origin (15,16). In the Ohio Valley, shagbark grows chiefly on north and east slopes of fertile uplands; in the Cumberland Mountains it is confined to the coves and the north and east slopes; and in Arkansas, Mississippi, and Louisiana it grows principally in river bottoms. Shagbark is found on better sites up to elevations of 910 m (3,000 ft) in the Blue Ridge Mountains of the Carolinas and on north and east-facing benches at elevations above 610 m (2,000 ft) in northern Arkansas. In northern Arkansas, shagbark hickory is often very common on clayey soils derived from Mississippian and Pennsylvanian shale formations and may represent nearly half of the stocking of privately owned woodlots on these sites.

Here in Ontario, the tree often grows alone or in small groups mixed with other hardwood forest trees and where dense Shagbark Hickory stands do exist we find evidence of anthropogenic roots to the ecological succession of those forests in centuries prior (in other words, dense shagbark hickory stands often indicate evidence of manmade indigenous food forests).

The range of shagbark hickory encompasses 7 soil orders and 14 suborders (24). Ultisols are the dominant upland soils in the southern half of the shagbark range while Alfisols and Mollisols are primary soil orders in the northern portion of the range. The soils within shagbark's range are derived from a wide variety of parent materials-sedimentary and metaphoric rocks, glacial till, and loess. The soils also represent a wide range in soil fertility, such as Alfisols and Mollisols which are high in base saturation to Ultisols which are low. Shagbark hickory is sensitive to changes in soil fertility. In the northern part of its range, the species is found on a variety of upland sites; in the southern areas, it is more common in the more fertile bottom lands and on the better north- and east-facing upland sites.

Associated Forest Cover

Hickories are consistently present in the broad forest association commonly called oak-hickory but are not generally abundant. Shagbark hickory is specifically listed as a minor component in six forest cover types : Bur Oak (Society of American Foresters Type 42), Chestnut Oak (Type 44), White Oak-Black Oak-Northern Red Oak (Type 52), Pin Oak-Sweetgum (Type 65), Loblolly Pine-Hardwood (Type 82), and Swamp Chestnut Oak-Cherrybark Oak (Type 91). It is also an associate in the Eastern White Pine (Type 21), Beech-Sugar Maple (Type 60), White Oak (Type 53), and Northern Red Oak (Type 55) forest cover types. Through most of its range, shagbark hickory is associated with oaks, other hickories, and various mixed upland hardwoods. In the South it is also associated with a number of bottom-land hardwood species.

Growth Form: Shagbark hickory is a medium-sized canopy tree averaging 21 to 24 m (70 to 80 ft) tall, 30 to 61 cm (12 to 24 in) in diameter, and may reach heights of 40 m (130 ft) with a diameter of 122 cm (48 in). The tree characteristically develops a clear straight cylindrical bole, but there is a tendency for the main stem to fork at one-half to two-thirds of the tree height.

Carya laciniosa, also known as the shellbark hickory, is a large, deciduous tree with a narrow, column-shaped crown. It has a straight trunk, strong branches, and a broad, thick form.

Growth form

Trunk: Straight and slender, sometimes splitting into large limbs once the canopy is breached

Branches: Strong, stout, and long, ascending in the upper crown and drooping in the lower crown

Crown: Narrow, oblong, or egg-shaped, depending on the growing conditions

Size

Can grow to be 60–80 ft tall, but can reach up to 100 ft

Trunks can mature to 3–4 ft in diameter

Bark

Gray and smooth on young trees, but exfoliates in long strips with age

Leaves

Odd-pinnate compound leaves, with 7 dark green leaflets that are broadly lance-shaped and finely-toothed

Leaves turn yellow to golden brown in fall

Flowers

Non-showy, greenish yellow flowers that appear in April–May

Fruit

Edible egg-shaped nuts encased in a thick husk that splits open in four sections when ripe in fall

Reproduction: Shagbark hickory is monoecious and flowers in the spring. The staminate catkins are 10 to 15 cm (4 to 6 in) long and develop from axils of previous season leaves or from inner scales of the terminal buds at the base of the current growth.

Habitat and Ecological Niche:

Canopy Layer Tree and potential Mother Tree.

Dry upland slopes, rich deep moist soils and well drained soils of lowland and valleys.

Flowering and Pollination:

Male and female flowers are borne separately on the same branch (monoecious). Male flowers are in clusters called catkins, 1½ to 5 inches long, pendulous in flower, in groups of 3 at the base of the current year's new branchlets. Flowers are yellowish-green with up to 10 hairy stamens.

Female flowers are tiny, clustered 2 to 4 at the tip of the current year's new branchlets. Flowers have a stout, yellowish to green, oval to egg-shaped ovary covered in minute hairs and tiny scales, and green stigma at the top.

Seed Production and Dissemination- Shagbark hickory are thought to reach commercial seedbearing age at 40 years (though given ideal soil conditions and ideal ectomycorrhizal (ECM) fungal association that timeframe can be cut down significantly). Although maximum seed production occurs from 60 to 200 years, some seed is produced up to 300 years. Good seed crops occur at intervals of 1 to 3 years with light crops or no seed during the intervening years. Tree diameter and crown size or surface are probably the best indicators of shagbark seed production. In southeastern Ohio, 6-year seed production of dominant and codominant shagbark hickory trees with mean d.b.h. of 20.7 cm (8.1 in) (age 60 years), 26.1 cm (10.3 in) (age 90 years) and 45.1 cm (17.8 in) (age 75 years) averaged 16, 36, and 225 sound seed per tree per year, respectively (17). Some individual shagbark trees have been known to produce 53 to 70 liters (1.5 to 2 bushels) of nuts during a good year. The germination of fresh seed is though to be 50 to 75 percent by most (though through applying Akiva Silver’s advice for maximizing germination rates I have seen 90-95% germination rates myself).

Several species of insects influence seed production by causing aborting or premature dropping of fruits or by reducing the germinative capacity of mature nuts. Especially serious are the hickory shuckworm (Laspeyresia caryana), pecan weevil (Curculio caryae), and the hickorynut curculios (Conotrachelus affinis and C. hicoriae). In good seed years about half of the total seed crop is sound, but in years of low seed production, insect depredation could be proportionally higher, and a very low percentage of sound seed is produced.

Hickory Nuts are not technically nuts… they are considered “drupes” or even "tryma". A drupe is a fruit with a single seed inside. So the “nut” of these plants have a soft fruit that dries and splits to reveal the seed… what we call the nut. A true nut is a fruit which forms a hard shell to cover the seed, and this hard shell (the fruit) does not split open on its own. Confused yet? It may be easiest to call it a nut!

Shagbark nuts are heavy, averaging about 220/kg (100/lb) and are disseminated primarily by gravity with some extension of seeding range caused by squirrels and chipmunks.

Health Benefits of Shagbark Hickory:

Shagbark Hickory was once an essential source of food, material, and medicine for native peoples of the eastern United States and Canada. The inner bark was mainly used in medicine. It is very astringent and may have diaphoretic, digestive, and emetic activities.

Externally, they would use the inner bark as a dressing for cuts and ruptured blood vessels and soothing arthritis. Internally, they would chew the bark for mouth sores or steep it as a tea for treating colds, menstrual problems, rheumatism, kidney problems, and heart issues.

Some modern research has deepened our understanding of native people’s use of this and other tree species. A 2000 study explored the antimicrobial activity of extracts from eastern hardwood trees, including Shagbark Hickory, and their relation to traditional medicine. The study found that these extracts were most active against gram-positive bacteria and filamentous fungi. It also showed a correlation between antimicrobial activity and medicinal use by First Nations people.

While not specifically those of the Shagbark Hickory, hickory nuts of all species are healthy foods. They contain high amounts of omega-3 fatty acids (more than cashews or peanuts). They also contain antioxidants like vitamin E and phytochemicals like plant sterols and flavonoids, which are beneficial to cardiovascular health.

In traditional Chinese medicine, hickory nuts are used for brain health. This use was also supported by modern research. A 2020 study found that the compounds in hickory nut extract “had activity to promote the neurite outgrowth in human SH-SY5Y cells.” (source).

History and Cultural Relevance of Shagbark Hickory (Carya ovata):

The tree typically grows mixed in with other canopy hardwood species but there are places in Ontario and Quebec (as well as many locations south of us) where highly concentrated old growth stands of shagbark hickory exist along side unnaturally high concentrations of other choice food and medicine producing tree species indicating intentional indigenous agroforestry design. That makes Shagbark Hickory a helpful indicator species for those seeking to learn from the horticultural knowledge of the ancients which (though they may not have written it down) is imbued and infused into the species distribution of certain forests and the soil composition which we can “read” today if we develop our pattern recognition skills sufficiently.

Pollen samples from the soil indicate these manmade food forests were created in various parts of the Eastern Woodlands of Turtle Island between 800-1500 years ago and many of them persist (and have become self-propagating and self-perpetuating food forests) even with the original indigenous horticultural architects of said manmade forests having been removed from that land for centuries now in some cases.

These places continue to produce an unusually high amount of food and medicine (that is well suited for the human diet and health) even though the original forest gardeners are no longer able to do their annual controlled burns and careful interplanting of key companion tree species (as pollen evidence indicates they engaged in for hundreds of years prior to European Contact) their forest gardens are still producing abundant food (for those capable of recognizing it) today.

The Jesuit Relations offers first hand observations by missionaries that were interacting with the Huron and Wendat people here what is now called Ontario in the 1600-s and they offer accounts of how the indigenous people lived in communities with longhouses and fields of corn, squash, beans and medicinal herbs on the periphery of said communities, and then further out those people tended what the Jesuit priests described as “well manicured orchards” that were spacious, composed of multiple nut and fruit producing species and allowed for the people who the priests described as “savages” to easily collect baskets brimming with nuts and fruit to bring back to their communities.

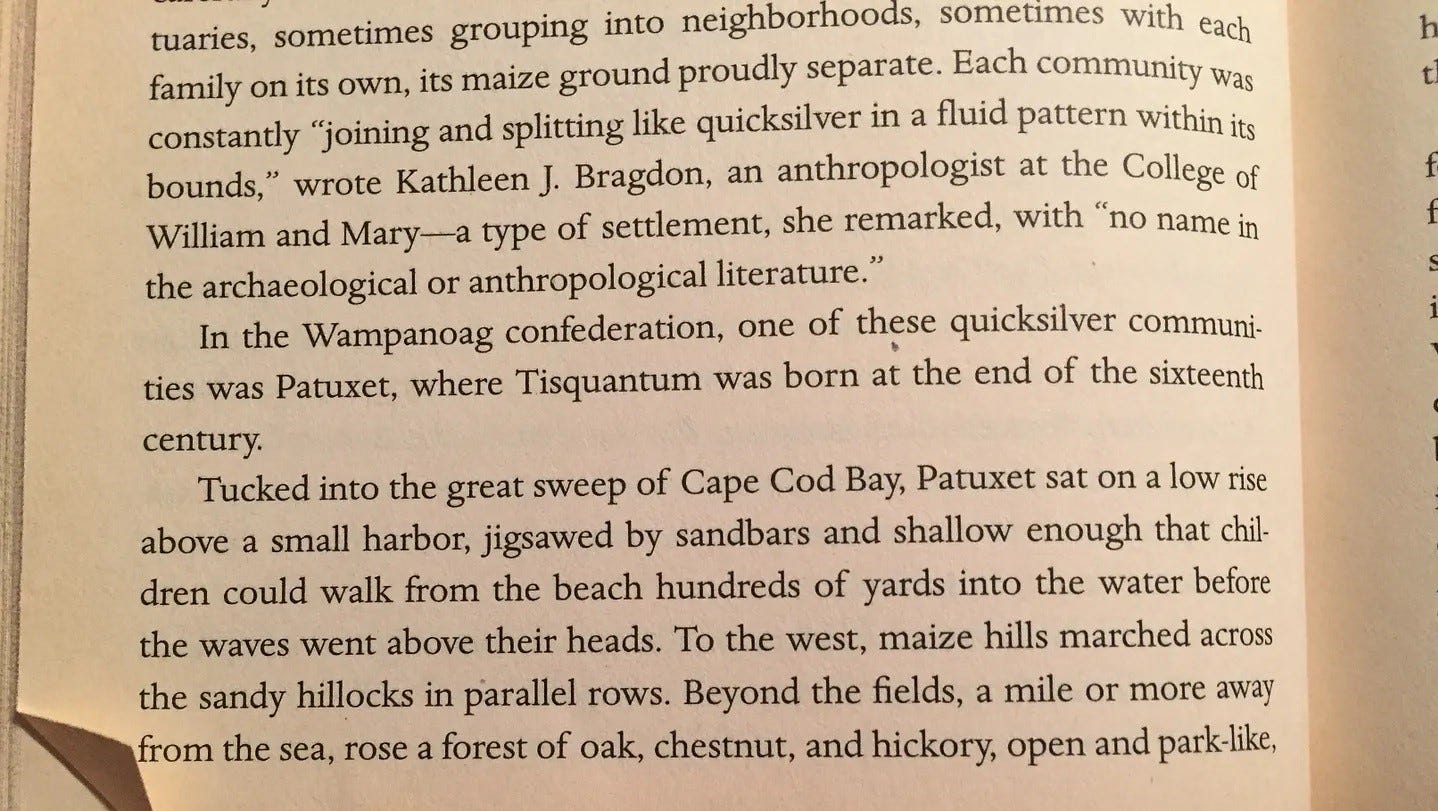

In 1491: New Revelations of the Americas Before Columbus by Charles C. Mann you can find other accounts of well tended to “orchards” and forest gardens near Cape Cod that were tended to by the people of the Wampanoag Confederacy. (a picture of one such page from the above mentioned book is shown below)

In the case of Shagbark Hickory, H. Bernard noted in 1980 that their distribution in Quebec, Canada, was “exactly the same as the Iroquois territorial supremacy at the time of the first settlement.” (Bernard, H. 1980. The nut trees of Quebec native and introduced. Ann. Rep. Northern Nut Growers Assoc. 71:21-25. ) There is also a direct account of Iroquois cultivation of American ginseng in 1716, when a French Jesuit “discovered” ginseng after it was introduced to him by some Iroquois. (He observed them gathering the plants by digging the roots when the seeds were ripe, and then scattering the seeds around the hole where they had dug.) Other plants with a probable history of indigenous cultivation include sweet grass (Hierochloe odorata) and wapato (Sagittaria latifolia). The evidence for the history of cultivation of these species in specific locations can be found, given enough effort.

London, Ontario was once the homeland of an Iroquoian-speaking people that the Huron called the Attawandaron and the French called the Neutrals. Their homelands extended all the way up the highway 401 corridor from Sarnia to Guelph, along the same path as the Deshkan Ziibi. These peoples had an alliance with the Mississauga Nation. This distinct group of Mississauga peoples spoke a dialect of Algonkian and thrived primarily at the mouths of the rivers leading to the Great Lakes.

Sometime around 1,200 years ago, this whole region was gradually converted to an Oak/Hickory Savannah food forest, accented by prairie grasses and wetlands, by design. A food forest is essentially what it sounds like. It is a strategically designed habitat that focuses on building up several layers of the ecosystem to ensure food for all parts of that ecosystem throughout each of the seasons, with a long-term vision for generational thriving.

Envision this for a moment: Over the course of time, specialists would have begun to map the land through storytelling, not on paper, and in turn share those stories amongst their community members so that a general map of the region becomes embedded within the consciousness of all members of the civilization.

These specialists would have been tracking the ecosystem’s progress, in all its diversity, including weather patterns, mineral locations, plant and tree growth cycles, fungi growth cycles, bird migrations routes and nesting patterns, mammalian den sites, fish spawning locations, reptile egg laying sites, and arthropod numbers, over time, to name only a handful. Based on pre-existing features of the land — such as wetlands, rivers, ground elevation levels, microclimates, and migratory patterns of some of the beings listed above — spaces would be selected where human habitation could be established.

I tend to see this manmade or ‘managed’ forest ecosystem as having six or seven layers by design. At the bottommost layer I think of root plants like wild carrot, sassafras, wild Canadian ginger and trout lilies. The next layer, though it could also be considered the underlayer, is the fungi and mycelium, things like turkey tails, oyster, giant puffballs, and chaga.

The next layer is the ground plant layer and throughout each season there are many that rise up. Not all of these are edible specifically, but all are medicinal. Think of strawberries, trillium, black cohosh and wild leek. Next you have the bush/small tree plants like raspberry, hazelnut and cedar.

As we continue upwards, the next layer is the medium-sized trees like Pawpaw , Saskatoon berry and highbush cranberry. Finally, the uppermost layer is the heavy nut producing trees like Oak, Sweet Chestnut, Shagbark Hickory, Black Walknut, Butternut, Chestnut, Tulip Tree and White Pine.

On the edges of the Food forest that transitioned into annual cultivation spaces for three sisters you would have Sumac, Elderberry, Anise Hyssop, Echinacea and Milkweed.

Hickory and White Oak were principal to the ancient food forests of southern Ontario, based on the abundance of nuts it produces each season and the limited amount of processing required to eat them.

Most of these foods and medicines must be enjoyed and processed at a specific time during the season, and all this ecological knowledge would have become embedded in the action-based education system, so training would have occurred for community members for the action of controlled burns.

Indigenous peoples were in possession of deep ecological knowledge passed down culturally through story, ritual, and tradition. Through ongoing symbiotic interactions with the plant beings around them, over time species increased in abundance. With the advent of integrated, ecological shifting cultivation systems, indigenous peoples were able to transform the landscape like never before.

The existence of cultivated quinoa-like chenopods in Ontario 3,000 years ago is evidence that an integrated shifting cultivation system existed already in the region before the Three Sisters cultural complex became dominant. Before the Three Sisters, indigenous people in the northeastern woodlands (modern day southern and central Ontario) were likely cultivating the seed crops chenopod (Chenopodium spp.), erect knotweed (Polygonum erectum), and sumpweed (Iva annua) as annual staple grains, during the initial stages of a cycle that evidence indicates included agroforestry (including cultivation of trees like Hickory) in the later stages. If you would like to read more about these the work by Natalie Mueller on the “Lost Crops” is worth checking out.

So agriculture, from polycultures of annual crops, transitioning to more advanced 50 plus year cyclical food forest plantations (which became permanent self-perpetuating food and medicine production systems as part of a highly advanced regenerative farming system had been being implemented on the land where I now live for literally millennia by indigenous horticultural experts.

Here are some more accounts of well tended to “orchards” (actually advanced regenerative agroforestry polycultures, aka “forest gardens” or “food forests”) in 1491: New Revelations of the Americas Before Columbus by Charles C. Mann. This time the accounts are regarding the Food Forests of the Haudenosaunee people from the area where I live now in the Eastern Woodlands:

So this land where I live used to be filled with highly advanced forest scale farming systems that were apparently indistinguishable from an intact climax forest ecosystem to the colonists (or at least regarded with as little respect as the non-tended “wild” Carolinian Forest that once existed here from horizon to horizon.

Here, today, in what is now called southern Ontario in the Eastern Woodlands of Turtle Island 99.98% of the primary Carolinian Forests and old growth food forests that once dominated the landscape from horizon to horizon have been cut down in the last 150 years.

What was once a thriving forest ecosystem with Paw Paw (Asimina triloba) groves thriving underneath a 100 foot high plus super canopy of Butternut, Eastern White Pine, Sycamore, Black Walnut, American Beech, Shagbark Hickory, Sugar Maple and Tulip trees with large tracts of anthropogenic food forest mixed in is now mostly GMO soy and corn fields, strip malls, hydroponic greenhouses, factories and concrete. Based on my research and field expeditions I estimate that no more than one tenth of once percent of the original forests (untended primary Carolinian Forest, which stretched from horizon to horizon as well as anthropogenic old growth food forests, which used to cover tens of thousands of acres here in Essex county alone) still exist today.

The most aggressive and arrogant deforestation of Southern Ontario (peaking in a clearcutting frenzy about 120 years ago) was in large part instigated and encouraged by the “Dominion of Canada” government putting out advertisements offering “free land” to anyone that would clear the forest, sell the old growth trees to the military for their ship masts and grow a monoculture annual crop on the land. The government propaganda conditioned settlers to view the forest as an “obstacle” and something that needed to be cleared to bring “order” to the land. One of the main motivations behind that push was to get people to do the dirty work of chopping down the 250-400 year old white pine to supply British with masts for the Navy to be able to perpetuate it’s war racketeering operations.

Of course, it was not “free land” being benevolently gifted to poor up and coming emigrants to help get them started (as the propaganda posters implied) is was blood soaked stolen land, and land that had been carefully tended for generations to create a multilayered self-perpetuating resilient and diverse food production system that the European colonists were to ecologically illiterate and arrogant to recognize for what it was.

I share this to illustrate how the vague government propaganda inculcated idea that many people have in their minds about European industrial civilization “improving” life here and “developing” the “natural resources” or “making use of land that was just going to waste sitting there for agriculture” is a flat out lie and a fallacy. This land was already being tended with purpose and the food cultivation system that was being implemented here for well over a thousand years prior to those clear cutting operations was far superior in every way to modern farming practices.

Similar stories of short sightedness and greed can be found of that time period to the south of us in Michigan.

One of the most vivid description of the Cultural Forests of Eastern North America I have encountered so far comes from an early pioneer from the state of Michigan, 1884. What he tells is a sobering testimony to what has been lost, but if we begin to remember, we can let it be so again:

“In the forest we found the whole family of oaks, of the Michigan family, some twelve different kinds, and among them the burr oak, bearing an acorn good to eat, and on which hogs would fatten. In the timbered lands were the new trees called the basswood, of which the best timber for building was made; and the black walnut, more valuable than cherry for cabinet work. It also bore a large and very rich nut, and with it were the whole family of the hickories, all bearing good eatable nuts. Besides these were the butternut, the beechnut, and the hazelnut, all bearing an abundance of their fruit. Throughout the woods we saw the grape-vine hanging from the trees laden with its fruit. We saw vast thickets and long rifts of blackberry bushes lately burdened with their tempting berries. And we were told that the woods and hillsides and openings, in their season were fairly red with the largest and most delicious strawberries, while the wild plum grew along the small streams, the huckleberry and the cranberry on the marshes, and the aromatic sassafras was found throughout the woods. The annual fires burnt up the underwood, decayed trees, vegetation, and debris, in the oak openings, leaving them clear of obstructions. You could see through the trees in any direction, save where the irregularity of the surface intervened, for miles around you, and you could walk, ride on horse-back, or drive in a wagon wherever you pleased in these woods, as freely as you could in a neat and beautiful park.”

“Pioneer Annals” by A. D. P. Van Buren, in “Report of the Pioneer Society of the State of Michigan”, Volume 5, 1884, pg. 250.

Just like here in southern Ontario, those ancient food forests in Michigan are all chopped down now except for fragment remnants.

Evidence indicates that regenerative agroforestry designs were being implemented by indigenous people of the eastern woodlands of Turtle Island 1,500 years ago. Some of the results can still be seen today, examples of the robust, anti-fragile subsistence systems practiced by indigenous Iroquoian peoples. If the indigenous cultural landscape could be seen four hundred years ago from a bird’s eye view, it would be a shifting mosaic of food and medicine producing anthropogenic ecosystems fluidly melding one into the other, and incorporating the full spectrum of diversity of species and habitat types.

When many people seek to learn about indigenous food cultivation systems of Turtle Island, they end up reading about the famous Three Sisters. Three Sisters appear consistently in the archaeological record as an integrated polyculture, starting in about 600 AD. The people of the Haudenosaunee Culture are thought of as the first farmers in the northeast, though the evidence now indicates that is an over-simplification given how that story says nothing about the ancient food forests that those same cultures created.

The indigenous inhabitants of this land were often selectively burned woodlands every autumn or early spring. Burning would have kept back the underbrush of fallen branches and brambles. Burning would have also eliminated bushes or kept them in small, coppiced forms where the tops are frequently killed only to resprout each season from the living roots. The burning would kill the fire-sensitive saplings of ash, elm, and maple, conserving the wide-open nature of an oak-hickory forest. Not only are shagbark hickory and bicolor oak trees resistant to damage by fire, but their deep taproots allow them to resprout vigorously in case a small, sensitive seedling tree should be accidentally incinerated.

In the wake applying fire selectively to the woods, in areas of full or patchy sunlight the groundnuts would form into a nearly solid groundcover, like poison ivy but edible, ready to be dug for sustenance at any moment of the year. The earthbeans Amphicarpaea bracteata would also form a solid groundcover but being more tolerant of deep shade, these may be found deeper within the forest.

The groundnuts and the earthbeans fix nitrogen, and the annual fires would decrease nut weevil pests, raise the soil pH toward neutral, and in the process increase the calcium and phosphorous available to the trees. This funnels important macronutrients needed for seed and nut development to the shagbark hickories and bicolor oaks, lending support to their annual-bearing potential and consistency, and positively influencing the size and abundance of the nut harvest.

When the Gayanashagowa or Great Laws of Peace of the League of Iroquois Nations were established along the shores of Lake Onondaga a thousand years ago, they brought an end to relentless warfare experienced by the early Iroquoian peoples. It is thought that the people of the Owasco Culture were those peoples. The Great Laws of Peace were revealed by the Great Peacemaker and translated through his spokesman Hiawatha, in the home of the Mother of Nations Jigonhsasee. The treaties served to establish a democratic confederacy known as the Haudenosaunee, or the “people of the longhouse.” To this day it is one of the longest running democratic societies in the world.

Like the longevity of the Haudenosaunee Nations, what is amazing to me is that in several places evidence of advanced food forest design (regenerative agroforestry farming systems) such as north of us on the shore of Lake Huron/Georgian Bay or beside Lake Owasco) centuries later, in tact tracts of an agroforestry system are still present, seen by the present-day composition of the forest.

This is a forest filled with staple foods, from root to crown: groundnut to hickory nut. This existence of this legacy agroforest paints a vivid picture illuminating how some of the first peoples of Turtle Island had mastered highly advanced and truly sustainable farming methods long before the arrival of the Europeans.

Each one of the scattered dense (non-linear) hickory stands I have studied locally (and north of us near Lake Huron) occupies an area ideal as seasonal camps for hunting, fishing, and gathering. Hickory is a species that requires a lot of calcium in order to thrive, so it is found in restricted habitats above floodplains and below slopes, where alluvial soils rich in nutrients like calcium get deposited. In many of the disjunct populations, the stands of shagbark are isolated, sometimes hundreds of miles away from the next stand. Several of the populations are associated with known archaeological sites. Here in southern Ontario, it is no different.

The unavoidable conclusion is that their seeds were brought here and planted by the human inhabitants of this place. And of course they would have planted them – these trees are regarded as anti-famine trees by indigenous peoples. So says botanist Diana Beresford-Kroeger, whose favorite tree is the hickory.

Bur oak (Quercus macrocarpa) growing alongside anthropogenic ancient shagbark hickory and Kentucky coffeetree (Gymnocladus dioica) are still found growing here as well. This bur oak – hickory association is not novel, but a repeating theme throughout the overlapping range of these two species. And like our bicolor oak – hickory duo, the bur oak fulfills a similar niche as the bicolor oak, (as well as the chinquapin oak) thus they can be considered interchangeable both culturally and ecologically (and nutritionally). The Kentucky coffeetree, a nitrogen-fixing leguminous tree, bears large bean pods with edible seeds. The Kentucky coffeetree fulfills a similar niche as the honey locust (Gleditsia triacanthos). These along with pawpaw groves are all found growing in unnaturally high concentrations in archeologically confirmed ancient indigenous community areas in Ontario, New York and elsewhere.

Like the Kentucky coffeetree, the honey locust bears large bean pods with edible seeds as well as an amber-colored sweet flesh inside the pods that is rich in sugar and very sweet to the taste. Honey locust pods, which sometimes contain up to 38% sugar by weight, is reminiscent of tamarind, and could be considered culturally analogous. An association between honey locust populations and native settlements has been noted before. Both the Kentucky coffeetree and the honey locust fulfill similar niches culturally and ecologically, and so they may be considered interchangeable. As nitrogen-fixing trees, they play important supporting roles to the other trees in the forest. The polycultural trio of oak, hickory, and bean tree appears to have been seen as playing a role similar to that of the Three Sisters. To use the language of permaculture, this is a guild.

Mainstream American (and Canadian) archaeology and anthropology has tended to view native farming systems centered around maize, beans, and squash through the lens of Western farming, which separates cultivated species from their surrounding ecosystems, maintaining annual plants indefinitely through repeated disturbance. Western agricultural practices make it easy to see differences between the domesticated and the wild, and from that perspective it becomes difficult to conceive of a seamless integration of cultivated spaces within the broader ecology. There are few examples of this kind of farming among European settler populations. And we tend to project our own experiences onto those of the past and onto other cultures.

For more insights on how our government education system, text books and modern day western science are woefully lacking, as they are missing a critically important piece of the puzzle when it comes to describing the nature of ancient indigenous food systems of Turtle Island, here is an expert from Akiva Silver’s book (Trees of Power: Ten Essential Arboreal Allies)

Native peoples, however, do not make such rigid distinctions as between the domestic and the wild. This difference of attitude goes to the heart of what sets Native American and European agriculture apart. Not maintaining a distinction between the cultivated and the wild, it becomes difficult to maintain rigid property boundaries. Whereas European agriculture was settled into fixed fields – a constraint wrought by private property enclosure – Native American agricultural fields were “free ranging” and communally owned. Always changing, shifting, fluid, and mobile. Their’s was a shifting cultivation (or “swiddening”). In practice it was worlds apart from the European agriculture.

If one visits Mesoamerica where the Lakandon and Yucatec Maya still practice their traditional milpa, they would realize how the maize-beans-squash complex represents only the early stages of ecological succession within a system of shifting cultivation incorporating hundreds of species from annual weedy plants all the way up to old growth forest trees. The maize-beans-squash crop complex has dispersed all across North America from Mesoamerica, and is known as the Three Sisters all throughout, from Mexico to Canada. The naming of the Three Sisters rests in story, and story provides context.

The milpa, a shifting cultivation system integrating agroforestry, is agriculture as conservation. The milpa is but one member of a family of indigenous cyclical cultivation systems found throughout the forested world. There’s the Tembawang system of the Dayak people of Kalimantan, Indonesia; the Huuhta & Kaski methods of the Forest Finns of Finland and Russia; the Landnam of the Scandinavian Norse; the Jhum cycle of northeastern India and Bangladesh; the Yakihata system of Japan. These integrative, indigenous systems born of deep ecological knowledge share in many features, like an impulse towards reforestation and ecological regeneration — they are the original restoration agriculture.

Trees are homes to a plethora of wildlife. They don’t need to be ripped out of the ground every year. Once they grow a little older, they become resilient defiant beings that don’t need to be coddled with irrigation, fertilizer, or weeding. The simple act of planting a couple of Apple trees could then transform overtime into hundreds of thousands of apples that could feed your family, birds, the soil, and contain seeds that have the potential to create new unique apple trees. The story of the landscape could change indefinitely.

Cultures all over the world of the past and present emanated forest gardening principles in their lives. This included Native Americans, the Chagga people who resided on Mount Kilimanjaro, the Maninjau people in Sumatra, people of the Maya Forest , the Baka people of the Central African rain forest, people of Portugal, and countless others. They all embodied methodology of forest gardening for meeting their most important necessities of life.

The connection of forests as food and the indigenous people of North America became very apparent when I came across a book by Kat Anderson called Tending the Wild. It’s an incredible book about the relationship indigenous peoples of California had with Nature, and it challenged what I had always been taught in school about the history of many Native American tribes. It is often regarded in anthropological documents and history that indigenous people were living a passive hunter gatherer life style and that they did not include agriculture in anyway.

As I discovered more through a range of book (and as I have evidenced above) I learned that this is simply not true. Indigenous people were deeply engaged with the land, planting seeds, pruning trees, initiating controlled burns, and harvesting in ways that gave back to the plants that they gathered from. They were saving seeds from plant beings that exhibited positive traits and planting them out. They drastically changed, diversified, and enhanced the landscape around them. They often stayed in one particular area for their entire lives.

Beyond the scope of hunter gatherers, they were/are also horticulturalists and intensive managers of the forest landscape around them. This way of partnering with forests are not only roots in their way of life. They are the whole tree, and the entire forest. Could it be that forest gardening is actually a much more sound way of creating abundant food bearing landscapes that were rich in healthful ecology?

Welcome to the anthropogenic forest. Overall it is an integrated and beautiful system, and still here centuries later. Cultural landscapes like these are the result of traditional ecological knowledge practiced for generations in place. Cultural forests may be difficult to recognize without the proper context. Indigenous people knew how to build robust, anti-fragile subsistence economies that seemlessly integrated with the broader ecology, and the continuing existence of these forests is testimony to their resiliency. Like the Haudenosaunee who have maintained their democracy for a thousand years into the present, their nut groves are still here, too.

These remnant food forests reveal a host of new questions leading us to deeper understanding and offer us wisdom as we plan how we will cultivate food for our communities going forward.

Forests and farms are exclusively separate in the present western world. Modern agriculture involves rows and rows of open fields, chemical inputs and machinery. Forests are viewed upon as primarily a source of timber or are largely protected as conservation land. What most people fail to realize when looking at our current food systems is that agriculture as we know it is a relatively recent way of interacting with the Earth. And often a very destructive one. For time immemorial, people lived and sustained themselves in rich ways within forest garden systems. This took place in nearly every part of the world, and still do in many parts today.

The question of how can we feed the world without destroying the Earth presses deeper into our current reality. An even more important question to ask is how can we feed our communities in a way that makes the Earth even healthier than before our interaction?

The more I learn to work with this tree the more clearly I come to realize that in climates and bioregions analogous to ours here in Southern Ontario, Shagbark Hickory (and his companion trees) offer one important part of an answer to the question above.

In the spirit of giving back to the living Earth, giving to the 7th generation down the line and beginning to regenerate the food forests of southern Ontario, I have donated several tree seedlings (which I grew from seed) to a group interested in regenerating the forest here. I was honored to be invited to help plant some of those seedlings as part of a Community Food Forest project recently.

We planted Echinacea, Pawpaw and Malus Sieversii seedlings, along with the first Shagbark Hickory seedling to be planted on a property designated for ecological regeneration, traditional food sovereignty initiatives and a community food forest.

Shellbark Hickory (Carya laciniosa) aka "The Kingnut" were considered the Anti-Famine tree of the Haudenosaunee Confederacy (meaning where these trees were planted and tended in great numbers, no humans ever starved). The nuts can be stored for multiple years and remain edible. They are nutrient dense with protein, healthy fats, minerals and medicine for preventing cancer and neurodegenerative diseases.

For more info on that cousin of the Shagbark and its potential in regenerative agroforestry here are a few pages from Our Green Heart: The Soul and Science of Forests (2024) by Diana Beresford-Kroeger pertaining to a tree she refers to as The Kingnut (or Carya laciniosa, the cousin of the Shagbark Hickory).

It brings my heart great joy to be able to offer my own gifts and hands to begin to heal the damage that was done by colonial agricultural practices.

I am grateful be part of efforts to plant seeds for the 7th generation that will come after us so they can have access to an abundance of food and medicine. I hope to be able to share more information from that project when I am able.

May those seedlings be the first of many and may they set down their roots deeply, providing not only food and medicine for us two legged beings, but also nourishment and habitat for our four legged and feathered relatives. So it is and so it shall be.

Functions In The Wilderness and in the Food Forest:

Ecological Functions:

Squirrels and birds relish the seeds and catkins. Fruit-birds, Fruit-mammals, Nesting site, Cover, Substrate-insectivorous birds.

Hickories serve as food for many wildlife species. Hickory nuts also are 5 to 10 percent of the diet of eastern chipmunks. In addition to the mammals above, black bears, gray and red foxes, rabbits, and white-footed mice plus bird species such as mallards, wood ducks, bobwhites, and wild turkey utilize hickory nuts. Hickory is not a preferred forage species and seldom is browsed by deer when the range is in good condition.

Host plant for Banded Hairstreak butterfly and many moths including the Luna moth. The nuts are eaten by a variety of wildlife such as squirrels, chipmunks, and black bears. Moderately resistant to deer. This plant supports Hickory Horndevil (Citheronia regalis) larvae which have one brood and appear from May to mid-September. Adult Hickory Horndevil moths do not feed.

Guild Profile:

In modern day New York, Michigan and Ohio some of the key species utilized in indigenous agroforestry flora guilds included:

hickory

bur oak, bicolor oak or chinquapin oak

honey locust

Kentucky coffee tree

pawpaw

toothache tree

cockspur hawthorn

groundnut

eastern camas

harbinger-of-spring

giant solomon’s seal

American hazelnut

thicket bean

American plum

earthbean

Other plants I would add to the list of potential guild members:

chestnut (Castanea dentata)

black walnut (Juglans nigra)

butternut (Juglans cinerea)

basswood (Tilia americana)

sumac (Rhus spp.)

serviceberry (Amelanchier spp.)

Viburnum spp.

currants (Ribes spp.)

raspberries (Rubus spp.)

blueberries (Vaccinium spp.)

strawberries (Fragaria spp.)

elderberry (Sambucus canadensis)

ramps (Allium tricoccum)

Here in southern Ontario, they grow and thrive among stands of Pawpaw, Butternut, Black Walnut, American Beech, Swamp White Oak, Basswood, Sugar Maple and Tulip trees.

Considering many of those trees offer their own medicinal and food gifts I would use those natural forest companions as inspiration for building the foundation of a Shagbark (or Shellbark) Hickory Guild.

Like the outstanding Shagbark Hickory, the swamp white oak or bicolor oak (Quercus bicolor) is exceptional for having some of the sweetest acorns in eastern North America, often edible raw right out of the shell with little hint of astringency from the tannic acid. The bicolor oak is capable of bearing annually, and can grow nuts that are moderately large in size.

Shagbark (or shellbark) Hickory wood can be used to cultivate shiitake mushrooms.

Oak and Maple are also powerful companions when one is planning on stacking mycological functions in a food forest design as both maple and oak logs can be used to cultivate nutrient dense medicinal and gourmet mushrooms such as Shiitake, Turkey Tail, Lion’s Mane, Reishi and Oyster mushrooms. If one is planning on a multigenerational scale for their food forest design, one could encourage choice saprotrophic mushrooms to colonize the downed logs of elder trees resulting in yet another layer of self-perpetuating food and medicine to be propagated at the ground level, along side your ground cover herbs and medicinal rhizomatous plants.

Butternut is another great contender for a protein producing companion canopy tree and if one lives further north, Sugar Maple and/or White Pine could make powerful allies for stacking functions in the food forest, kitchen and medicine cabinet.

Understory guild partners could include Pawpaw trees, Elderberry, Serviceberry, Haskap berries, Raspberries Anise Hyssop, groundnut (Apios americana), Canadian Wild Ginger, Bloodroot, Ginseng and wild leeks (Ramps).

Using our understanding of flora used in ancient indigenous agroforestry (combined with modern and localized adaptations) we might emulate how the ancient food forest designers of the eastern woodlands may have been incorporated into an integrated shifting cultivation cycle.

We might group these assemblies of flora into sections representing the different phases of ecological succession:

The garden or vegetable phase, characterized by Three Sisters maize-beans-squash multicropping/intercropping, also including sunflowers, tobacco, and possibly other plants like chenopods, knotweed, or sumpweed. Located primarily on the arable lands in valleys and floodplains.

The old field phase characterized by hazelnut, pawpaw, plum, hawthorn, serviceberry, and including species like toothache tree, sumac, viburnum, raspberries, blackberries, highbush blueberry, elderberry, strawberry, groundnut, earthbean, thicket bean, etc, and grasses. When left untended these old fields may rapidly turn into thickets, but eventually will give way to closed-canopy forest.

The mixed woodland phase, characterized by oaks (bur oak, bicolor oak, and more), hickories, walnuts (black walnut, butternut), American chestnuts, honey locust, Kentucky coffeetree, basswood, etc. (I would add American persimmon to this list but I can find no record of it past or present in this study region of western and central New York.) Forest trees are becoming established, but the canopy has not closed. Reduced light to the forest floor and changing trophic relationships with animals gradually result in the retreat of old field / thicket species, and the advance of forest herbs and roots like harbinger-of-spring, American ginseng, eastern camas, solomon’s seal, ramps, and the host of spring ephemerals.

The forest phase, characterized by closed-canopy tree cover and stable species representation. Mostly indistinguishable from “wild” forest – you’d have to look closely or find an over-abundance of cultural plants to tell the difference.

Additionally, we might group some flora assemblies into habitat types outside of or parallel to the phases of the shifting cultivation cycle:

A savanna phase characterized by widely-spaced fire-managed oak-hickory associates (shellbark, shagbark, bicolor oak, bur oak) interspersed with nitrogen-fixing tree crops like honey locust or kentucky coffeetree. May include maples, elms, chestnuts, basswood, etc. The understory could be comprised of grasses, groundnut, camas, giant solomon’s seal, harbinger-of-spring, strawberry, currant, and others. This phase is very similar to the mixed woodland phase (#3), but is maintained in a more open state through frequent firings, OR may exist outside the alluvial areas away from places that come under cyclical cultivation. These savannas might be located along the gentler slopes above the valleys, for instance.

A steady, or final phase, defined by its long-term consistency and/or unsuitability for other purposes. This phase could apply to areas with semi-aquatic root gardens (wapato, etc.) or to steep, non-arable places, or to wet fens or bogs, or nutrient-poor areas where succession creeps very slowly, such as sand dunes, shale barrens, etc. Such places may contain any number of different species including oaks, chestnuts, cranberries, strawberries, pines, hemlock, birches, maples, blueberry heath, etc. These areas might be characterized by a relational quality of “low-level tending,” rather than by the particulars of a habitat type.

Traditional Medicinal Uses:

Many tribes ate the nuts raw as a seasonal treat and others boiled the nuts down to make a cooking oil. The Winnebago, Dakota, and Cherokee boiled down the nuts along with their shells to create a soup. In areas where there were no maples or sycamores, hickory sap was used to make a sweetener and syrup. The Iroquois boiled and ground up the nuts to make baby food and mixed this same mash in with their corn pudding or corn soup. Many tribes ground the nuts to make a nut meal to make different breads. Ground nuts and honey were also used as a breakfast food. The Cherokee, Meskwaki, and many other tribes dried and stored the nuts for winter use.

Native Americans also used hickories medicinally. The Ojibway and Chippewa peoples steamed the young shoots and leaves to make a drug to treat headaches and convulsions. The Cherokee chewed pieces of hickory bark for sore mouth and throat ailments. The Potawatomi applied the liquid from boiled bark to sore muscles and arthritic joints. Other tribes made hickory bark infusions to keep their muscles pliable during hunting and athletic events. The Iroquois mixed hickory sap with bear grease to make a bug repellent.

Many different indigenous peoples of eastern Turtle Island had a great amount of uses for hickory bark as fiber for basketry and bindings. The wood was used for hunting supplies, implement handles, and building. The Cherokee utilized the inner bark for chair bottoms and baskets. Whereas the Iroquois and Omaha used the bark to make snowshoe lashings as well as using the wood to make the rims of their snowshoes. Hunting supplies such as arrow shafts, blow gun darts, and bows were made from the strong elastic wood. The Seminoles and Cherokee made barrel hoops, tool handles, and containers from the wood.

Shagbark’s young shoots/leaves were used by the Ojibway for headaches. The Potawatomi boiled the bark and applied it to tender muscles for arthritis pain.

As noted above, the word hickory is derived from the Algonquian word, “pawcohiccora”, describing an oily nut milk made from pounding hickory nut kernels that had been boiled. This sweet nut milk was used by the Creek in their hominy and corn cakes.

Practical Uses:

They produce some of the finest tasting nuts around. The nuts are similar to pecans and the trees are very cold hardy. They don’t get very much attention as a food crop simply because their nuts are difficult to extract, but with the proper tools this becomes an easy task! These trees also produce some of the strongest wood around that is used for bows, axe handles, and furniture. Huge untapped potential to be a source of perennial proteins and oils.

Produces mulch yearly from bark, leafstalk and nut husks

Bark makes a yellow dye which was patented in the 18th century

Believed by many to be the most delicious nut

Shells are incredibly hard, this is why they are not usually grown commercially for food (yet this also speaks to their potential for being used to make resilient bio-char for soil amending and enriching).

I like to use the hickory nut shells to make bio-char with a top-lit updraft gasifier (TLUD) stove which I then gift back to the Earth in an enriched format so that the nuts gifts can continue to give back in another way (and to countless other trees and beings into the distant future as well) through permanently enriching and building local soils.

Primary Uses:

Nut – Raw. Excellent taste in Hickories.

Nut – Cooked. Used in desserts, breads, baking, etc.

Nut – “Milk” can be made from Hickory nuts

Nut – Oil. An edible oil can be pressed from Hickory nuts

Secondary Uses:

General insect pollen plant – attracts beneficial insects which feed on the pollen of these trees

Wildlife food

Wildlife shelter

Windbreak plant

Sap is edible (Hickories) – can be tapped like Maples and reduced (with heat) to make syrup. I have yet to try this syrup, but the reports on flavor I have found range from very good to fair and slightly bitter. Interesting.

Wood used for poles, posts, fence posts, stakes, tool handles (axes!).

Wood used for fuel (firewood), charcoal.

Wood is a great wood for smoking meats.

Dynamic Accumulator – Potassium and Calcium for all species; Phosphorus in Shagbark Hickory (C. ovata)

Biomass Plant – large tree with lots of leaf-fall every Autumn that can be left to decompose and build the forest soil, or it can be moved and used in other places or composted.

Yield:

Hickories can produce at least 100 lbs (46 kg) on mast years when they are 25-50 years old.

Harvesting: Autumn. Hickory are typically harvested after they have fallen from the tree; however, some people (and commercial operations) use nets to catch the nuts during harvest season.

Some nuts will fall early-avoid all of these. Trees may reject nuts for a number of reasons, typically the ones I see that fall early are nuts that have been aborted for some reason, or those that have insect damage.

Processing:

After collecting the nuts you can put them in a five gallon bucket of water and the ones that float are to be discarded (or better yet made into biochar) as they have been compromised in some way and are not edible.

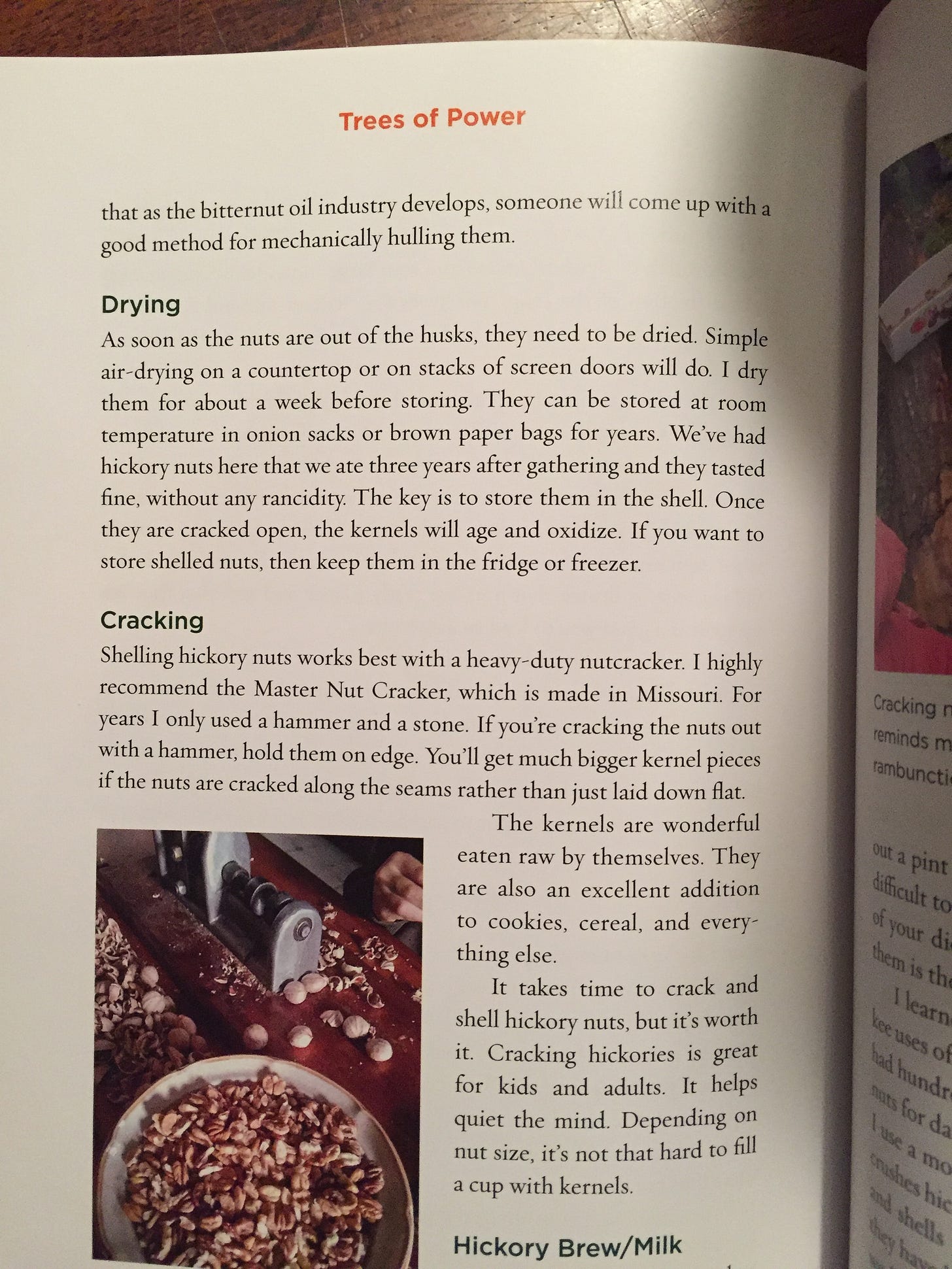

Cracking and shelling hickory nuts

Most shagbark hickory nuts I see are about an inch wide, but some are smaller. Whatever size you have, know that getting them to crack them open without crushing the nut meat is a learned skill.

Admittedly, I'm not very good at cracking them yet, but the Grandpa's Goody Getter nut-cracker has a hickory nut attachment some people have used with good results.

Getting the X

The old-school method Sam Thayer described for cracking hickory nuts involves striking the nut shell on the wide side in a way that makes an X. Using a hammer, put the nut on a flat surface and strike it lightly.

Ideally, there will be three or four fissures, which will make removing the nuts from the shell easier.

If you want to crack them the old-school way, you'll also want a nut pick and a snips. Sam Thayer explains how to make a homemade nut pick by flattening a nail and putting it into a piece of wood.

Additional Helpful tips for shelling and processing the nuts can be found here: https://foragerchef.com/the-foragers-guide-to-shagbark-hickory-nuts/

Storage: Can be used right away, though some say curing them results in better flavor. If the nuts are dried, they can store for a few years.

Whole hickory nuts will last you several years if they are stored in a cool, dry place. They will last you even more years if you stick them in the freezer. Even better yet, store them in a vacuum seal in the freezer.

Other Uses:

Role in Nature:

Active (though endangered) participants in our local ecosystems, shagbarks are often found in association with oaks in oak-hickory forests. The hard outer husk of the hickory nut splits open when it’s ripe, making them particularly desirable to chipmunks, squirrels, rabbits, and mice, as well as many species of birds which forage from the trees in the fall.

Shagbark hickories are also vital because of the habitat they provide to a more underappreciated neighbor: bats. It has been well-documented that many bat species, including big brown, little brown, silver-haired, and hoary, use shagbark hickory trees as day roosts. The bats crawl up under the curls of bark and sleep there during the day, emerging in the evening to devour thousands of insects per night. Bats prefer roost trees with a larger diameter, meaning that, if we wish to help our local bats, we should protect habitats that foster hickories for long periods of time, allowing them to grow very large. The USDA estimates that bats provide “billions of dollars in ecosystem services annually,” and notes that they are especially important to farmers because they eat insects that would otherwise require costly (and environmentally degenerative) insecticides to control.

Shagbark hickories take part in the forest phenomenon known as “masting,” when, every two to five years, all of a forest’s trees of a particular species grow a bumper crop of nuts (oaks, pecans, and others also exhibit this behavior). Some people speculate that this behavior may lead to an increased chance of seed survival, as the creatures who eat the nuts may leave more behind in a mast year. This masting behavior has ecosystemic effects for years afterward, often leading to a boom in prey populations such as deer and squirrels, which then reduces again in non-mast years.

Being a tree that produces abundant protein, this species is a strong contender to become a “Mother Tree” (focal points of wildlife activity and leafy vitality, “Mother Trees” are foundational to providing a localized ecosystem with a biodiverse food chain of mammals).

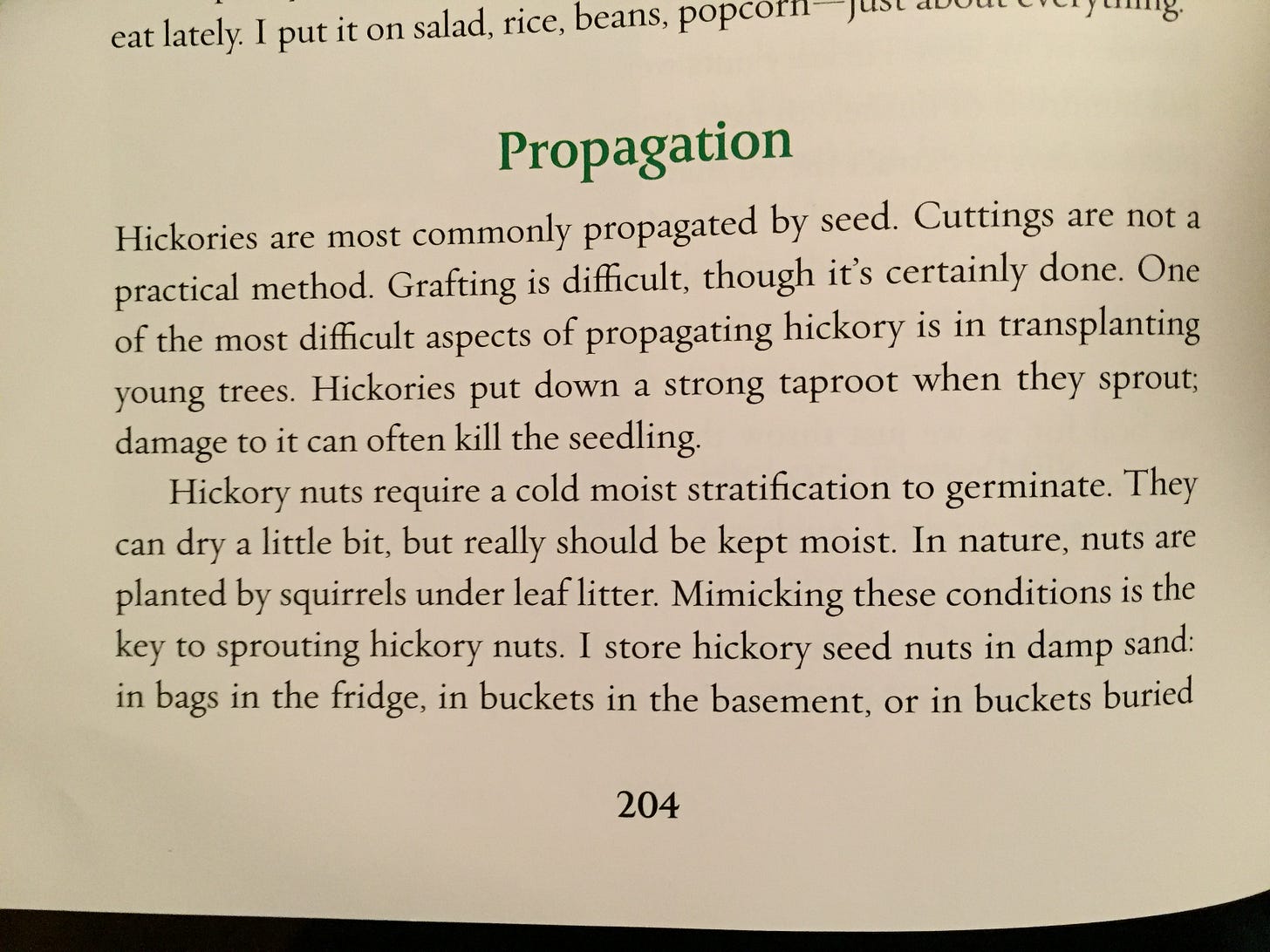

Seed Propagation:

Seed - requires a period of cold stratification. It is best sown in a cold frame as soon as it is ripe. Stored seed should be kept moist (but not wet) prior to sowing and should be sown in a cold frame as soon as possible.

Air pruning beds are ideal for propagation from seed due to the aggressive tap root.

For more info on Air Pruning beds:

If you have to sow in pots, where possible, sow 1 or 2 seeds only in each deep pot and thin to the best seedling. If you need to transplant the seedlings, then do this as soon as they are large enough to handle, once more using deep pots to accommodate the tap root. Put the plants into their permanent positions as soon as possible, preferably in their first summer, and give them some protection from the cold for at least the first winter. Seed can also be sown in situ so long as protection is given from mice etc and the seed is given some protection from cold (a plastic bottle with the top and bottom removed and a wire mesh top fitted to keep the mice out is ideal)

Seed/Seedling Sources:

Canada:

Seeds:

https://www.incredibleseeds.ca/products/shagbark-hickory-seeds

For anyone in Ontario looking for good quality Shagbark Hickory nuts for eating (or propagating) check out Robert James Hyatt's page https://www.facebook.com/RobertJamesHyatt/posts/pfbid02cf26JPnzaJuvmGJAy86QS1cynUPLbUNCXPjzzPmdKmUV61tj7HanT6VwfSkaqfDyl

Seedlings:

https://www.hardyfruittrees.ca/produit/nut-trees-grown-in-canada/shagbark-hickory-carya-ovata/

https://silvercreeknursery.ca/products/shagbark-hickory-seedling

https://www.grimonut.com/index.php?category=hickory-hican&p=Products

US:

Seeds:

Seedlings:

Cultivation details:

Light: Full sun to light shade

Shade: Shagbark Hickory (C. ovata) can tolerate a bit more shade than the other species, however his relative the The Pecan (C. illinoinensis) doesn’t like any shade.

Moisture: Medium soil moisture preferred. The Shagbark Hickory (C. ovata) can tolerate some fairly dry periods and doesn’t like wet soils or flooding.

pH: prefer fairly neutral to alkaline soil (6.5-8.0)

Shagbark Hickories are self fertile but will produce more nuts if there are multiple Hickory trees in proximity to one another.

Years of Nut Production per tree: minimum of 100 years, but most will be productive for at least 200 years. It is not uncommon for trees over 400 years old to still produce large yields.

Thus, it is an ideal species to ally with in the spirit of giving to the 7th generation down the line.

Shagbark Hickory Recipes:

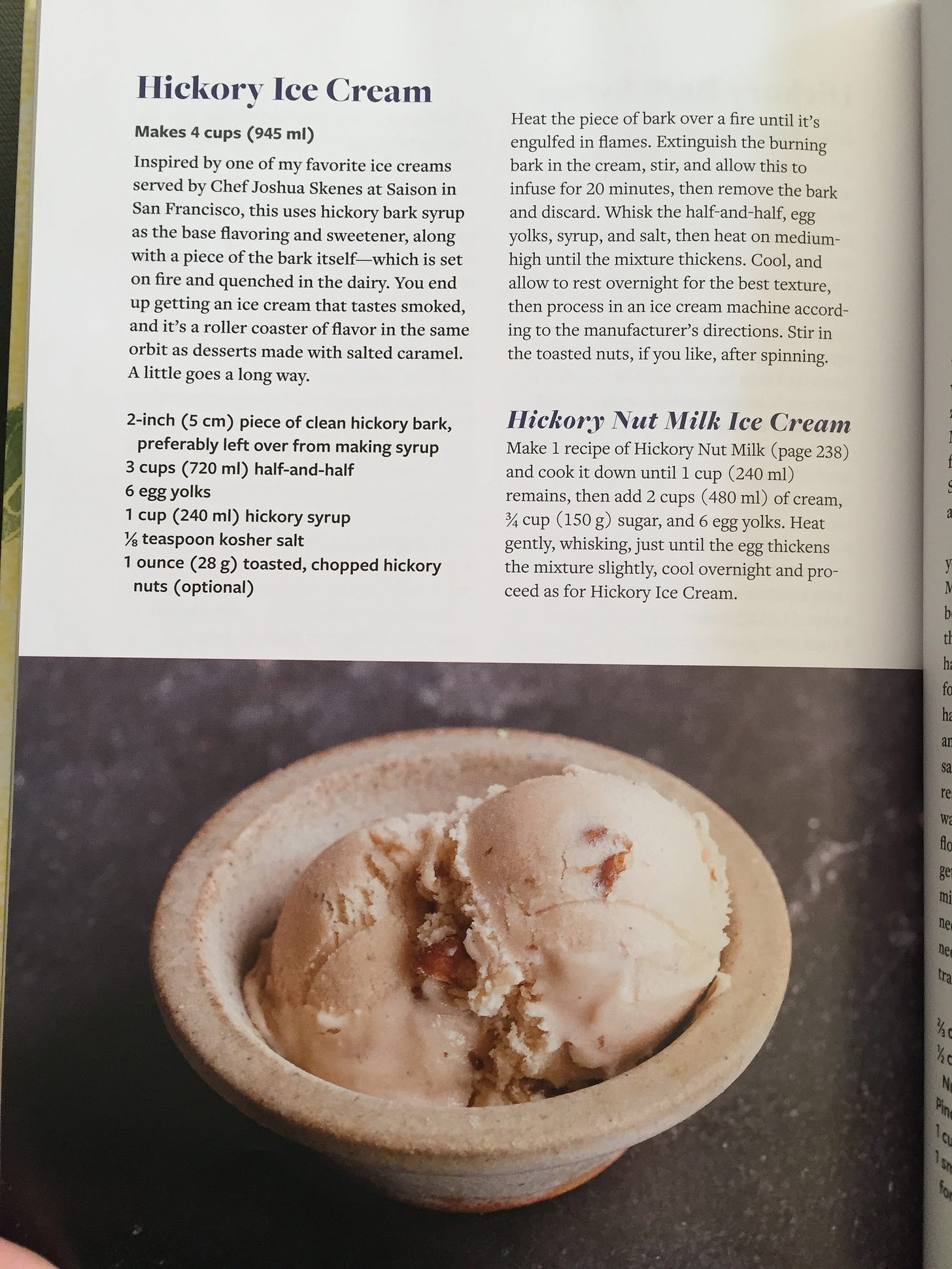

When cracked and perfect, hickory nuts taste buttery and delicious like a pecan-never rancid, stale or musty. The nuts are edible raw, fresh from the shell and there's no need to toast them.

The cracked nuts can be used anywhere you'd use pecans. Hickory nut pie is a classic, but you'll need a couple cups of nuts. If you only have a few, they're great just eaten out of hand or sprinkled on a salad.

This year used some of our Pawpaw harvest to make icecream and topped it with foraged Shagbark Hickory nutmeat for a nutritious and delicious Carolinian forest flavored desert for our thanksgiving meal.

Other recipe ideas and pertinent book excerpts:

Shagbark Hickory has excellent flavor for sweet treats. Try Shagbark Hickory Syrup.

Impress your friends at a holiday cookie swap with these Wild Hickory Nut Shortbread Cookies from Serious Eats.

Create your own delicious, traditional hickory nut milk (Kanuchi) with these simple instructions from The Forager Chef.

Try a cake recipe that has been passed down for three generations with this Grandma’s Hickory Nut Cake recipe from Taste of Home.

Make a great foraged meal with this Wisconsin Ramp Pesto that uses delicious ingredients like parmesan cheese, olive oil, ramps, and hickory nuts.

Kanuchi and Hickory Nut Milk

Kanuchi, an indigenous method of bashing the nuts, shell and all to a rough mash before simmering in water to make nut milk is the most ingenious method of processing hickory nuts I know of as you get to bypass the tedium of shelling the nuts. It's by far my favorite hickory nut recipe. (source)

Pawcohiccora (Shagbark) Hickory Soup

The word pawcohiccora (sometimes spelled powcohicora) is an Algonquin word that refers to both the Shagbark (or Shellbark) Hickory, and is in fact the word from which the loan word hickory in English derives from, and a kind of soup/nut milk made from several types of native nuts. Shagbarks are one of the stars of harvest season--they taste a bit like very sharp maple syrup. Commercial nut milks have become all the rage, and more and more home cooks are making the stuff at home. If you have ever made homemade coconut milk, then you will be familiar with the process. For the most part, Shagbark hickory nuts are not available commercially, so they either have to be harvested in the wild or grown. But pecans or walnuts can always be substituted, in fact any nut will work.

https://nativefoodblog.blogspot.com/2013/10/pawcohiccora-shagbark-hickory-soup.html

References:

https://foragerchef.com/the-foragers-guide-to-shagbark-hickory-nuts/

https://www.songofthewoods.com/hickories-carya-spp/

https://practicalplants.org/wiki/carya_ovata/

https://storymaps.arcgis.com/stories/b5806dff2f424ee8937b03c0213c6cc0

https://thedruidsgarden.com/2013/11/07/tree-profile-hickorys-magical-medicinal-and-herbal-qualities/

https://www.naturalmedicinalherbs.net/herbs/c/carya-ovata=shagbark-hickory.php

https://practicalselfreliance.com/shagbark-hickory-tree/

https://pfaf.org/user/Plant.aspx?LatinName=Carya+ovata

https://tcpermaculture.blogspot.com/2013/03/permaculture-plants-pecans-and-hickory.html

https://www.srs.fs.usda.gov/pubs/misc/ag_654/volume_2/carya/ovata.htm#:~:text=Growth%20and%20Yield%2D%20Shagbark%20hickory,122%20cm%20(48%20in).

https://archive.org/details/1491.newrevelationsoftheamericasbeforecolumbusbycharlesc.mann

https://www.gutenberg.org/files/44669/44669-h/44669-h.htm

https://www.nomadseed.com/2020/11/owasco-agroforestry/

The above post was the 17th installment of a series titled Stacking Functions in the Garden, Food Forest and Medicine Cabinet : The Regenerative Way From Seed To Apothecary.

Imagine old growth food forests existing where you live, with a multilayered canopy of native food producing trees above, berry and fruit shrubs below, medicinal herbs and rhizomes at ground level and medicinal gourmet mushrooms growing all around on the logs of the first generation of that forest that are giving their bodies back to the Earth. That is the kind of abundance we are capable of gifting to the 7th generation down the line from us if we choose it.

This educational work is intended to inspire people to re-imagine what it means to be human in the through providing knowledge that empowers people to become the co-creators of de-centralized (and scalable) centers of amazing abundance/biodiversity in their local bioregion (such as the old growth food forests that Charles C. Mann documented early "explorers", missionaries and military officers encountering in his book, 1491, where he shared excerpts from Jesuit priest and New France military people looking in awe upon the "well tended and park like nut and fruit orchards" that existed along side the Haudenosaunee communities they were encountering in the 1600-s, near where I live now).

We can find ways to work with local indigenous people now to apply the techniques and traditions of their knowledge keepers along side modern soil building techniques that accelerate soil regeneration along with mycological stacking of functions to begin to regenerate the food forests that once dwelled on much of Turtle Island for all our communities going forward.

The food forests I am working on co-creating will be both Refugia, soil seed banks, food production systems, medicine production systems, regenerative fiber/construction production systems and places of prayer and spiritual nourishment.

I hope this inspires you to try foraging from and/or planting Shagbark Hickory trees where you live so that you can plan for an abundant and resilient future while also thinking of the 7th generation that will come after we are gone.

Here is to planting amazing native food bearing trees like Shagbark Hickory all over and creating neighborhoods brimming with low-maintenance, nutrient dense and local ecology conducive food stuffs.

I know times are tough for many right now due to government scams and oligarch chicanery deflating the value of our currency and exponentially increasing grocery/energy bill costs I am currently offering a limited time 50% off sale on Annual Paid Subscriptions to my newsletter.

I am doing this so that getting access to the heirloom seed bonus offer I describe in this post (which can be turned into exponentially increasing amounts of nutrient dense food and medicine year after year) is more affordable for those going through tough times and also so those that want to support my educational, ecological regeneration and heirloom seed protection endeavors can do so in a way that may be more manageable at this point in time.

The link to the 50% off annual paid sub sale can be found below:

It would be great if we could incorporate some of this into real "Earth Science" classes taught in school. Young people would grow up with a better appreciation of our natural environment and not want to destroy it with (unrecyclable, heavily cemented anchored) windmills for example. They would also lean toward natural cures as opposed to Big Pharma. Maybe it's wishful thinking, but I'm sowng seeds here. Perhaps homeschooling course.

I would absolutely love to incorporate into my poly culture here in central Vic Oz but the almost complete lack of summer rain and very low summer humidity is the limiting factor.