Pines - nobles of the global woodlands

Exploring the many gifts offered by Pine trees in the context of Food Forest Design. This is Installment #18 of the Stacking Functions in the Garden, Food Forest and Medicine Cabinet series.

This post serves as the 18th post which is both part of the above mentioned (Stacking Functions in the Garden, Food Forest and Medicine Cabinet : The Regenerative Way From Seed To Apothecary series) as well as constituting the 5th installment of the Befriending The Boreal series.

There are many species of Pine, however, as is the case with Birch trees, covering them all comprehensively in the context of Regenerative Agroforestry would require writing an entire book. Thus, I will be focusing on several main species (listed in large bold letters below). These are either the species I am most familiar with and have worked with extensively in both Ontario and BC, or they are species I am learning about, and/or experimenting with harvesting from and cultivating now as they are ideal for including in Food Forest designs for temperate (and some semi-arid) climates.

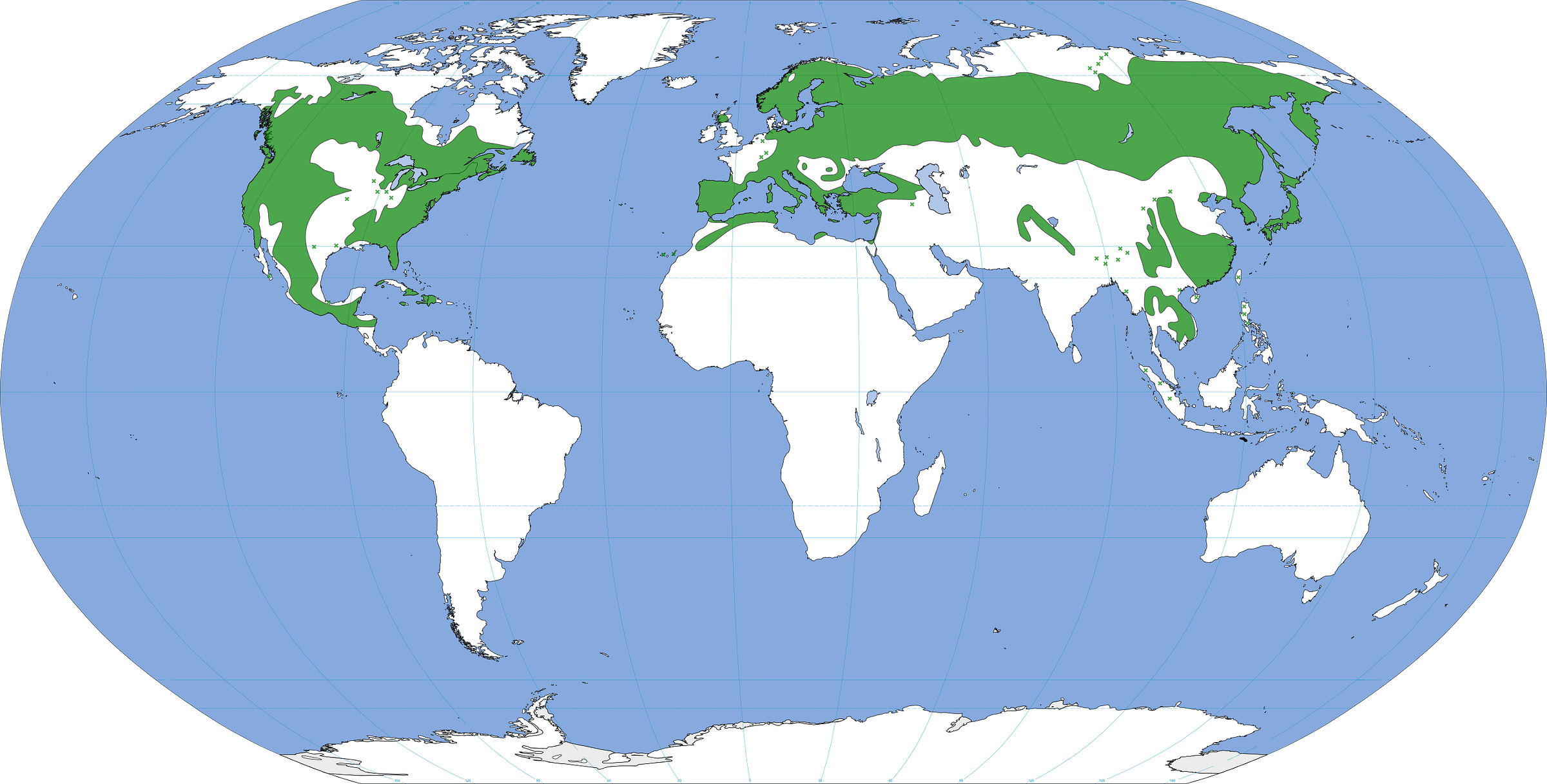

For the edible nut pines, they have many advantages over some other deciduous nut trees in the fact that they may be grown in a more far-reaching range of climatic zones, across not only all parts of Ontario; but also Canada, United States, and large portions of Asia and Europe ranging from Zone 1 to 8.

The species I will explore here will include:

Pinus strobus, Pinus monticola, Pinus resinosa, Pseudotsuga menziesii, Larix, Tsuga canadensis, Tsuga heterophylla, Pinus Sylvestris, pinus koraensis, Pinus cembra (and Pinus cembra ssp. sibirica) and Pinus monophylla

Pine trees (and other trees that are in the Pinaceae family) have always been close to my heart. Growing up in the midst of the towering Douglas Fir and Western Hemlock of the coastal range along the sea to sky corridor (from Whistler to Van city) and exploring the babbling brooks where forest transitions to alpine meadows in the mountains underneath the larch trees these beings have a special place in my heart.

I would spend entire days exploring around the base of 500 year old plus giants as a child, laying down on their moss covered roots underneath their majestic canopies, leaning against their deeply furrowed bark and listening to the wind make their branches and foliage speak. While that was nourishing to my heart and spirit, I only began to discover how many medicinal and even nutritional gifts those beings also offered as a young adult.

In more recent years, after moving out east, I fell in love with the Eastern White Pine and the Eastern Hemlock as I explored in the wooded lakes and rolling hills of the Eastern Woodlands.

I discovered that the towering white pines provided nesting habitat for Bald Eagles, Osprey, Hawks, Owls and a range of other birds and marvelled at the amount of Reishi mushrooms growing on the fallen logs in old growth Eastern Hemlock groves. The more I learn about these majestic, noble, long lived and generous rooted beings the more I realize how underutilized these trees are in permaculture and food forest designs.

With my research and creative energy now focused on Regenerative Agroforestry and Food Forest design I wanted to re-visit a number of species that I have begun to experiment with integrating into food forest guilds and regenerative medicine garden designs in the hopes I might inspire some of you out there to get yourself a handful of seeds for a pine species (which produces edible foliage, seeds and pollen) that grows well in your area and make the long term investment into the gift economy of planting some of these “nobles of the wood”, so you can watch them grow, and so you can allow future generations to also be able to receive their many gifts.

In a similar way to what I described in my article on Birch trees, this ancient tree family is found in al most the entire Northern Hemisphere meaning that the pine tree is one of those tethers to the ancient indigenous histories of all people who have ancestors that called the northern hemisphere home. In fact, for those of us in the northern hemisphere, I would go as far as to say that each and every one of our respective ancestors had a close relationship with at least one type of pine tree and that it played an integral part in their daily life, their traditions and their means for surviving.

Thus, the tall rooted elder beings of the pine family offer a sacred reminder of a time before arbitrary lines were drawn in the sand by statists for greed and ego back to an era when many of our ancient ancestors knew the trees intimately and had a reciprocal relationship with them. Long before people were swearing allegiance to kings, queens and flags they were swearing allegiance to the living Earth and recognizing our ancient kin (such as these Nobles Of The Global Woodlands we know as Pines) and the many gifts they shared with us.

If your ancestors hail from the northern hemisphere Pine trees offer you a sort of universal language to perceive the common ground you share with the ancestors of those now residing in nation states far and wide. This tree offers you a glimpse into your own indigeneity and your ancestors relationship to place. Yes all of us have an indigenous past connected to our blood and our soul. For some of us, that indigeneity is buried under multiple millennia of bloodshed, oppression, re-writing of history and statist propaganda. Though it may be buried deep and many may have sought to erase that part of your heritage from the stories of modern cultures, this part of you exists nevertheless. This part of your ancient heritage when you ancestors lived close to the land and the forest, recognizing more than human beings as deserving of our respect as conscious beings.

After you read the article below and learn about all the beauty , blessings and the many gifts offered to us by Pine trees I invite you to take a moment next time you see one to touch his bark, smell his foliage as you look upon him with gratitude and reverence for all that he shares with the world you will be choosing to see the world through the eyes of your ancient ancestors.

Through seeing trees like Pines as those who’s blood flows in your veins now did millennia ago you begin the unlearn the lies, self important delusions and separation mentality that is inherent in modern civilization. In that act to see the noble Pine tree with the understanding and reverence of those who came before you and walked the earth with respect eons ago, you are building a tangible bridge that connects you to your honoured elders and ancestors and a bridge that also directs you towards a more Regenerative, humble and hopeful future.

Such are the blessings we are given when we learn to see the living earth and our rooted elder kin as the ancients did, as wise teachers, protectors, healers, sources of inspiration, regeneration and renewal.

When we learn to perceive and interact with our rooted kin (such as the pine tree) as our ancestors did we shatter the modern illusion of separation that nation states attempt to impose on us and begin to speak a universal language that connects us all as equals.

Growing edible pine nut trees is a great addition to a cold climate food forest. Some of the edible pine nut tree varieties are cold hardy to zone 1. If nothing else might grow, pine nuts could still grow. Some varieties can also grow in the arid regions of southern US and Mexico so these trees can provide a critically important source of protein and healthy fats in an extremely long lived perennial crop.

The edible pine nut trees also make beautiful ornamental trees and can be part of a shelterbelt.

Many of these species can live for many hundreds of years, they are extremely resilient to the cold, drought tolerant and they produce several forms of food and medicine that though often unrecognized, are nutrient dense and highly beneficial medicinal gifts which can become an integrated facet of a multi-generational food forest design.

My ancient Gaelic ancestors had a reciprocal and reverent relationship with one of these species (Scots Pine, or Pinus sylvestris in their case). The Druidic traditions (evolving into the Brehon Laws of ancient Ireland) placed a special emphasis on honoring the beings they considered to be “Nobles Of The Wood”. They so revered the Pine that he was given an honored standing in their living Ogham tree alphabet.

The Celtic Ogham A stands for Ailm. Ailm means conifer – or Scot's Pine. In their tree lore the conifers of Ailm are associated with healing, and a person's life work and divine purpose. These nobles or “chieftains” of the kingdom of our tall standing rooted kin were protected under ancient Brehon law.

In ancient times the medicine women and men of my indigenous Gaelic ancestors tribes (the Druids) would prescribe not only pine needle tea, pine needle infused baths and pine needle poultices but they would also prescribe walking in a pine forest as a type of medicine in and of itself. They were well aware of the benefits of this thing that some call “Forest Bathing” in modern times and encouraged those seeking healing and improved health to spend time in the midst of these nobles of the wood to receive their many gifts.

Thus, it feels apt that I now invite you to come on a journey with me as to learn more about our rooted elders in the Pinaceae family and imagine ways in which we can weave reciprocal relationships with these beings into our lives and our communities as we seek to align with the wisdom of the ancients that saw forests as the best design structure for how to grow food and medicine.

Family: Pinaceae

Part used for medicine/food: foliage (“needles”), cones, seeds, pollen, resin/pitch, bark.

Constituents:

Edible pine needles (such as Pinus Strobus and the other species listed above) contain many beneficial constituents useful for the prevention of colds and flu such as Suramin, Alpha-Pinene, Beta-Pinene, Beta-Phellandrene, D-Limonene, Germacrene D, 3-Carene, Caryophyllene, vitamin A, and vitamin C. Eastern white pine needles also contain shikimic acid.

Edible Pine seeds (such as the seeds produced by the species mentioned above): Lutein, Zeaxanthin, Vitamin E (tocopherol- alpha and Tocopherol-gamma), Calcium, Copper, Selenium, Vitamin C, Thiamin, Riboflavin, Niacin, Pantothenic acid, Vitamin B-6, Folate, Choline, beta-Carotene, Beta-sitosterol, Tryptophan, Threonine, Isoleucine, Lysine, Phenylalanine, Tyrosine, Valine, Glutamic acid, Glycine and fiber.

Edible Pine (and spruce) Pollen:

Pine (and spruce) Pollen has over 200 bioactive compounds:

Including phytoandrogens, antioxidants, flavinoids, essential amino acids, vitamins and minerals – including:

– Brassinosteroids: bio-identical to DHEA and testosterone

– Glutathione (helps with glyphosate detox)

– 20+ Amino acids (complete profile)

– MSM (methylsulfonylmethane) MSM has anti-inflammatory and antioxidant effects. Sulphur, which is a major component of MSM, plays an important role in making collagen and glucosamine, both of which are vital for healthy bones and joints, and in the production of immunoglobulins, which help your immune system.

– Superoxide Dismutase (anti-inflammatory)

– Vitamins: C, D, E and B’s

– Calcium, magnesium, potassium, silica, copper, manganese, molybdenum, selenium, zinc

The pollen grain carries everything it needs for germination. 15% amino acids, 1-2% lipids-sterols, various polyphenols and antioxidants, including 2% flavonoids, myoinositol, phosphatidylcholine, phosphatidylethanolamine, phosphatidylglycerol, phosphatidylserine, lignin, and various polysaccharides (complex sugars)—two of which are vital to immune health; arabinogalactan, and xylogalacturonan and on top of that boasts liver detoxifying agents like glutathione, MSM, SOD.

It also has vitamin D2/D3, magnesium, selenium, silicon, potassium, calcium, iron, strontium, phosphorus, sulphur, chlorine, manganese, and various other vitamins, minerals, and essential amino acids such as L-dopa and Arginine that help with blood flow and the nitric-oxide cycle. (Wild harvested Pine Pollen goes for $127.00 CAD per 80 grams (less than 3 ounces)

Edible Pine Bark: phenolic compounds, including monomers (catechin, epicatechin and taxifolin), and condensed flavanoids (procyandins and proanthocyanidins) [17]. Pycnogenol also contains phenolic acids, such as caffeic, ferulic, and p-hydroxybenzoic acids [17].

Medicinal actions: anticoagulant, anti-inflammatory, anti-leishmania, antimalarial, antimicrobial, antioxidant, antitumor, analgesic, antibiotic resistance modulation effects, cytoprotective properties, nutritive, expectorant, circulatory stimulant, mild diuretic, pectoral, immune stimulant, grief support, anti-cancer, anabolic, pro-survival, antiviral, stem cell/immune response activation, vulnerary, pain reliever, antiseptic qualities, and “drawing” preparation to remove splinters and anti-aging effects.

Pharmacology:

Pinene

A monoterpene found in the essential oils of many plants, including conifers, juniper, and cannabis. Pinene has many pharmacological properties, including:

Antimicrobial: Pinene has been used to treat respiratory tract infections for centuries.

Antifungal: Pinene can be used as a fungicidal agent.

Anxiolytic: Inhaled α-pinene has been shown to have anxiolytic effects.

Sleep enhancing: Oral administration of α-pinene can increase the duration of non-rapid eye movement sleep (NREMS) and reduce sleep latency.

Pine pollen

A rich source of macronutrients and bioactive compounds, pine pollen has many health benefits, including:

Antioxidant

Anti-inflammatory

Optimizes Reproductive Health

Antimicrobial

Antiviral

Anticancer

Hepatoprotective

A plant-based extract from the bark of pines, is used to produce “Pycnogenol” which has been used to treat inflammation and improve health. Research suggests that Pycnogenol may improve cognitive function.

Pine tar

A medication used to treat itchy, inflamed, and flaky skin conditions.

Cold Hardiness: 1-8

Native Range: All throughout the northern hemisphere. They are particularly abundant in mountainous areas, though also present in the flatter areas of the Eastern Woodlands of Turtle Island and are a key part of taiga (boreal forests), coniferous forests, and mixed forests.

Here are some regions where pine trees are native:

North America: There are 49 species of native pines in North America, (including the white, hemlock, tamarack, douglas).

Mexico: Mexico has the highest species diversity of pines.

Europe, Mediterranean, and West Asia, East Asia and Southeast Asia: including (Pinus Sylvestris, pinus koraensis, Pinus cembra (and Pinus cembra ssp. sibirica among others)

Himalayas

Pine trees are evergreen conifers that produce cones that contain reproduction seeds (which are often edible). They can survive in extreme weather conditions, such as deserts and rainforests, but they prefer mountainous regions (in general).

Growth Form: Widely Varies based on species and soil/climate where they are grown (growth form info on individual species covered in this article listed below each species spubsection.)

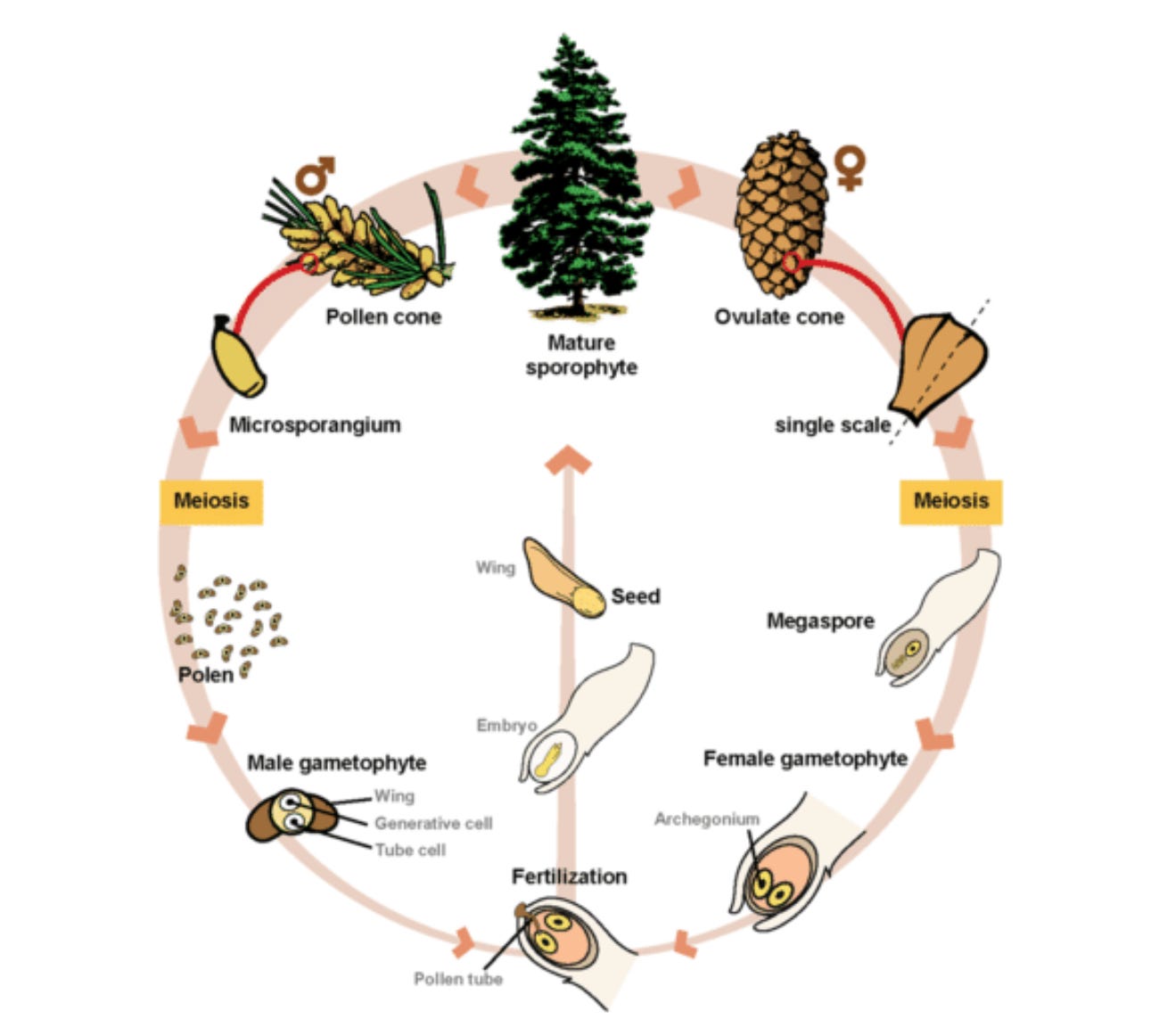

Reproduction:

Pines reproduce by seed, a multigenerational unit, which in the case of conifers contains both an embryo and the female gametophyte that produced the egg that was fertilized to form the zygote that grew into the embryo.

Recipes:

Each of the species covered here can be used in the recipes below with regards to foliage (needles), pollen, cones, seeds, bark and sap/resin.

My own more recent take on the soup above:

Cream of Pine and Mushroom Soup (with fermented ramp leaves, nettles and sea greens).

Pine Needles

Pine needles are also quite pleasant tasting when prepared in an ideal way. Their needles are rich in vitamin C (particularly White Pine), and can form the basis for a lovely winter (or spring) immune tea, especially when combined with Rose Hips, and Ginger. I have also experimented with adding diced up pine needles to fermented preserves such as sauerkraut and kimchi (pics shown below) which turned out beautifully.

Pine needles are perhaps the most versatile part of the tree. Believe it or not, even more than pine nuts, as they can be made into a tasty tea, or mixed into just about any recipe savory or sweet for a spicy kick. They’re also medicinal, which is a lovely bonus.

Externally, pine needles are added into salves for skin care “because pine is astringent, it reduces pore size and fine wrinkles. And pine is a powerful antioxidant which means that it may help to prevent premature aging, and may even help to reverse skin damage.”

Adding pine needles to homemade bath salts can help relieve headaches, soothe frazzled nerves, relieve muscle pain and treat skin irritation. A pine needle hair rinse can be used to treat dandruff and eczema while adding shine to your hair.

Internally, pine is high in vitamin C, which makes it perfect in a nutrient-rich pine tea or pine needle soda.

Pine needles are also naturally antibacterial, antifungal and expectorant so they make a great pine cough syrup when combined with honey.

Besides their medicinal uses, pine needles are just plain tasty. They add a peppery winter warmth to Douglass Fir infused eggnog or pine needle vodka.

As notes above, I also love to add diced up pine needles to fermented preserves, such as sauerkraut and kimchi.

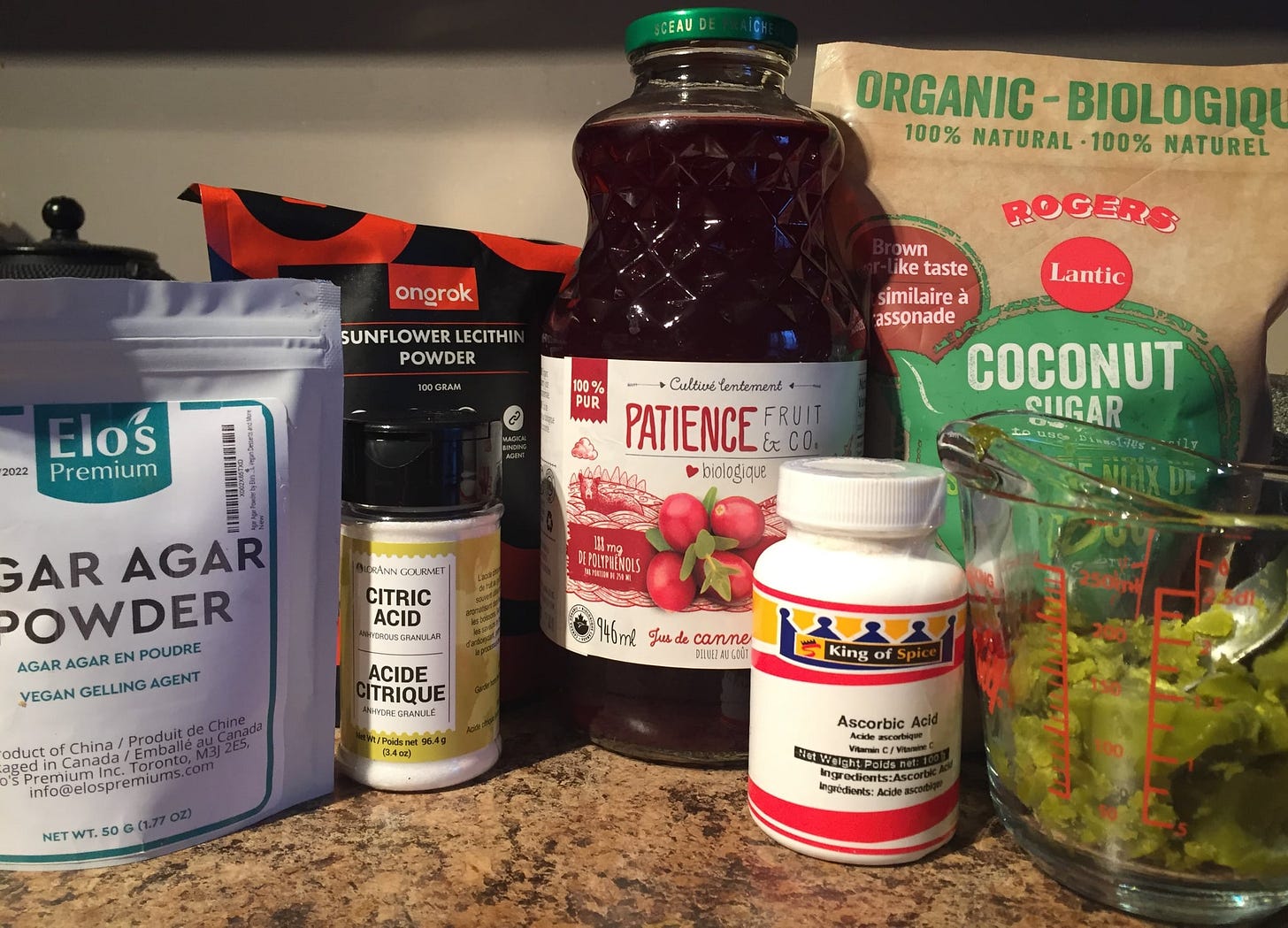

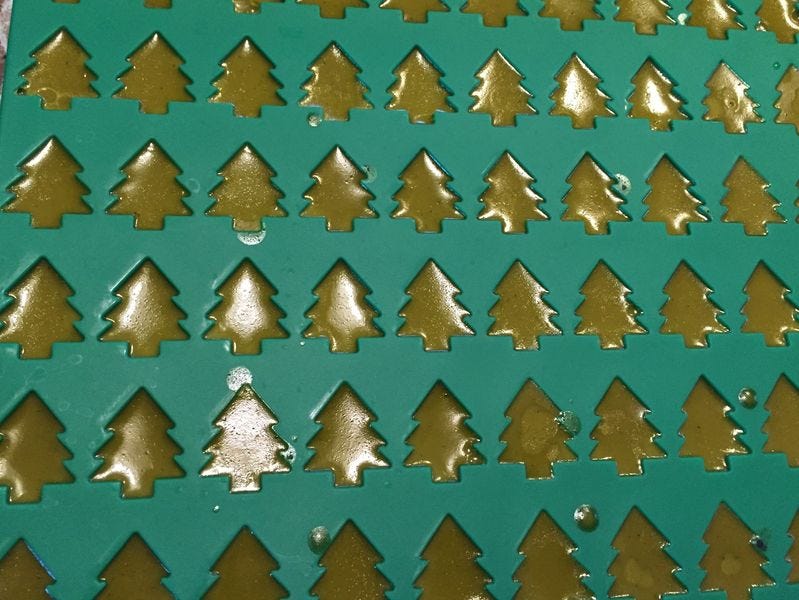

I have also experimented with using a cheap espresso machine to extract the essential oils/beneficial compounds from the needles after which combined with some other ingredients and made pine needle infused immune system optimizing ‘gummies’ (pics shown below)

I began using an espresso machine to extract essential oils and other beneficial compounds after I came across two studies where researchers had utilized an off the shelf espresso machine to extract potent medicinal phytochemicals (such as Eugenol from Cloves and Shikimic Acid from Star Anise).

An espresso machine creates conditions similar to the conditions used in industrial essential oil extracting processes (pressurized hot water extraction at approx 90.5 to 96 degrees Celsius with water/steam at 7-15 bars of pressure).

That paper is published in Science Direct and was also published in Organic Letters in 2015, and appears as a PDF at the University of Oregon website.

From the abstract of that study:

ABSTRACT: A new, practical, rapid, and high-yielding process for the pressurized hot water extraction (PHWE) of multigram quantities of shikimic acid from star anise (Illicium verum) using an unmodified household espresso machine has been developed.

This operationally simple and inexpensive method enables the efficient and straightforward isolation of shikimic acid.

In other words, they are taking advantage of the pressurized chamber of an espresso machine to conduct a heat + pressure extraction of shikimic acid from star anise.

And then this second study using similar methods to extract another beneficial compound: https://www.scribd.com/document/475104899/37-11

I share this info relating to using off the shelf espresso machines to extract essential oils and beneficial phytochemicals so that any of you DIY-ers and intrepid herbalists/natural medicine enthusiasts out there can experiment with using this technique increase your ability to make powerful homemade medicines with your favorite herbs (including foliage from all of the species covered in this article).

Buttery cookies and cakes really compliment the spicy conifer needle flavor, like in these redwood needle shortbread cookies, or these Douglass fir shortbread cookies. Similarly, pine needle sugar cookies strike just the right balance between earthy spice and sweet.

I love the idea of incorporating Douglass fir needles into a pear tart, as both pears and conifer are wonderful winter flavors.

For something delicious and dainty, try your hand at these profiteroles with Douglas-fir, orange, and cinnamon crème patissiere. (Don’t be too intimidated by the name – they are basically cream puffs, and they sound spectacular!)

A smart way to incorporate pine needles into various meals with only one recipe is this pine needle salad dressing, which will compliment a bowl of fresh garden greens, but I would also love to try it as a marinade or drizzled over braised veggies.

Add some woodsy flavor and vitamin C to your next herbal tea with a spoonful of pine needle infused honey.

Pine salve is great for dry, cracked skin! Infused with the aroma of pine, this easy-to-make herbal salve not only moisturizes and heals but also offers a delightful aromatherapy experience.

Pine Pollen

This stuff is a lesser known medicinal superfood and goes for $127.00 CAD per 80 grams (less than 3 ounces) but you can forage for and grow your own for free if you have patience.

Most people know of pine pollen as that annoying yellow powder that blankets their cars and sidewalks in the springtime. Once your neighbors start complaining about their dirty cars, it’s time to get out foraging.

Pine pollen season is short, and it’s variable depending on climate. Many pines produce cones way out of reach 50+ feet in the air, but if you can find smaller trees, or large trees with low branches, you can harvest your own pine pollen.

Pine pollen can be used to replace flour in most recipes, provided you don’t replace more than 1/4 of the total amount.

For more on Cooking with pine pollen:

https://foragerchef.com/pine-pollen/

Pine Bark

Harvesting pine bark often causes severe damage to a tree, and bark should only be harvested from trees destined to be cut down for other reasons. Pine bark has been harvested for food for hundreds of years, and one reason we know this is because the scars of pine bark harvesting are still present in Scandinavian trees after more than 700 years.

According to the Herbal Academy’s online Botany and Wildcrafting Course, “As a rule, never harvest from the trunk of a living tree. Only harvest bark from a tree that has been recently cut down for some other reason or has recently fallen over on its own. The timing here can be tricky, as you only want to harvest from recently fallen trees (within a few weeks of falling or being cut down) and not those that have begun to rot and decay. Never, absolutely never, cut a tree down simply just to harvest its bark or its root bark. This is not only unethical, but unsustainable, and is the reason why so many tree species used in herbalism, such as slippery elm (Ulmus rubra), are currently at risk from over-harvesting.”

The author of A Boreal Herbal notes, “The inner bark (cambium layer) has long been used as a survival food and can also be eaten in raw slices. I like to use the soft, moist, white inner bark for making pesto. Most pesto recipes call for pine nuts. But one day, when I was making pesto I didn’t have any around. Remembering the flavor of the pine’s inner bark, I thought, why not? I’ll try it. It was wonderful— I haven’t used pine nuts since. The inner bark contains lots of starch and many sugars and can be boiled or ground and then added to soups and stews.”

Tamarack (aka Larch) is a related conifer. In Rogers Herbal Manual, Herbalist Robert Rogers gives a recipe for tamarack bread: “Scrape off the softwood and inner bark of tamarack, mix with water, and ferment into a dough to be mid with rye meal. Bury under the snow for a day. As fermentation begins, the dough can be cooked as a camp bread or as dumplings, the sweet wood pulp acts as a sugar for the yeast in the rye.”

Both the inner and outer bark of pine trees has been used as a food source by the Sami, an indigenous people from northern Scandinavia, and not just as a famine food.

The inner bark especially is a rich source of vitamin C, and as Nordic Food Lab notes, “The phloem of the pine is rich in ascorbic acid (Vitamin C), which during the 1800s helped the Sami of the interior of Norway and Sweden avoid the scurvy that was at the time devastating the coastal populations of non-Sami farmers.”

Flour made from the inner bark contains about 1/4 of the calories as wheat flour, but since it’s a good source of scarce vitamins it was eaten by the richest in society. The outer bark is not rich in calories, but it was also ground into flour to help bread and crackers keep, and because it contains tannins that science has since shown to support healthy cell function.

Pine Sap, Resin or Pitch

Similar to harvesting bark, intentionally wounding a tree to harvest pine resin will scar a tree and provides access to insects and microbes that could stunt or kill the tree. Harvesting from small branches or existing wounds is a better more ethical option. Only harvest resin from the trunk of a tree that’s destined to be cut down for other reasons. If you have a mature pine tree in your garden, food forest or a pine stand in a forest nearby, and you are observant, you will inevitably witness instances where natural events wound a tree and the resin or pitch begins to flow out, coagulating either on the bark or the ground nearby, and that is a great opportunity to harvest this versatile substance for saving for later use.

Sometimes woodpeckers will help you have such an opportunity

For more info on the tree I sourced the Scots Pine Resin from above read:

Pine resin is used medicinally for a variety of issues, both internally and externally. Externally, it’s made into a pine resin salve that is very effective against rashes, but “It’s also an effective healing agent on cuts and bruises, helps to draw out splinters, and can be rubbed on your chest for congestion.”

It’s naturally antibacterial, so pine resin has been chewed as a gum for mouth complaints as well as sore throats. A tea made from pine resin is supposedly good for arthritis as well.

I have found the pitch or resin from the White Pine to be an extremely useful remedy for any external wound or infection. This is not the same as the sap. The sap is the fluid that runs inside the tree through its vascular tissue.The resin is found anywhere on the outside of the tree where there has been some previous wounding to the trunk. The resin forms as the trees method of healing sort of like our own skin would form a scab. Please, keep this in mind when you are gathering, as this is the trees' protective mechanism. I am careful to only gather loose or dripping resin. In the warmer months, the resin will be stickier and sometimes even almost liquidy. It is then that it can be used as natural stitches that will hold the edges of a wound together. It is also amazingly drawing and will draw out slivers, pus and infections while at the same time providing antispetic medicine that will reduce and prevent infection. When it becomes colder out the resin becomes hardened and more difficult to remove. This is when I will look for loose pieces that just chunk off. These can be softened by making an infused oil and then a salve. Infused oil of Pine resin must be heated well and I suggest a hot water bath either on top of the wood stove or any conventional stove top. Here are detailed instructions from New Mexico herbalist Kiva Rose on how to make Pine pitch(resin) salve.....http://bearmedicineherbals.com/pine-pitch-salve.html

The resin or sap from pine trees has a variety of uses, most of which don’t involve eating it. It’s been used to create waterproof sealants for clothing and can be made into a wood stain/waterproofer. It’s also used as an impromptu glue and firestarter.

For more info:

Pine Resin: How to render it for remedies : https://www.naturalbodylab.com.au/blog/pine-resin-how-to-render-it-for-remedies

How to Forage & Use Pine Resin : https://unrulygardening.com/forage-use-pine-resin/

Processing Pine Pitch for Use in Personal Care & Health Products: https://redheadedherbalist.com/harnessing-pine-resin-for-skincare/

How to prepare Winter Medicine with Pine Tree Resins: https://apothecarysgarden.com/blogs/blog/preparing-winter-medicine-with-tree-resins

https://www.savvyjack.us/blog/pine-resin-survival-uses

https://thenerdyfarmwife.com/pine-resin-soap/

https://theherbalacademy.com/blog/make-pine-resin-salve/

https://www.naturalbodylab.com.au/blog/pine-resin-how-to-render-it-for-remedies

For some scientific studies that provide additional context on Pine resin processing and storage:

"Effect of Temperature on Various Rosins and Pine Gum" :

https://pubs.acs.org/doi/10.1021/i360027a006

"Effect of heat treatment at mild temperatures on the composition and physico-chemical properties of Scots pine resin" :

"Quality aspects during pine resin storage: Appearance deterioration, turpentine chemical components change" :

"A study of the physico-chemical properties of dried pine resin" :

For more info on my recent experiments with pine resin read this comment.

I have used heated resin to seal up holes in my work boots and they held together for months longer than I expected.

Pine Cones

Some of you may be thinking. Pine cones!?!? Those can’t possibly be edible. Well, I thought that too until I followed the instructions in Alan Bergo’s Forager Chef book and made myself a jar of Muglio (aka Pine Cone Syrup) and is it ever delicious!

You can also use them to make a traditional Russian preserve called Varenye.

Pine cones, specifically young, meristematic/tender ones can be eaten, and are traditionally used in the Caucuses and Russia in a preserve known as Varenye, sometimes called pine cone jam, or pine cone honey.

Apparently, they are edible and were eaten historically. According to A Boreal Herbal, Indigenous peoples in Canada consumed not only the bark but also the cones of subalpine pine and fir trees. “The cones can also be used as food. They can be ground into fine powder, which in the past was mixed with fat. The result was considered both a delicacy and a digestive aid.”

Pine cones can be used to add flavor to dishes. There is a traditional Mongolian bbq recipe that involves by smoking mutton over a slow burning fire of pine cones. That practice sounds like it would imbue a lot of great flavor and I imagine it could be adapted for roasting other types of food as well.

Pine Seeds (aka pine “nuts”)

These tasty and nutritious little beautes can run you $46.33- $120.00 per pound here in Canada depending on the year but you can harvest and grow your own if you have patience and plan ahead.

Here are some ways to use pine nuts in cooking:

Pesto: Pine nuts are a classic ingredient in pesto, and toasting them enhances their flavor. You can also try making a pesto with wild ramps instead of garlic.

full recipe for pesto from my first book Mushroom based dishes: Pine nuts pair beautifully with umami flavors.

Rice Dishes: pine nuts offer protein and a lovely texture to balance out rice based dishes.

Salads: Pine nuts add crunch and flavor to salads. You can try tossing them into a lemony kale salad with golden raisins.

Crusts: Pine nuts can add flavor and crunch to meat or fish crusts.

Dukkah: Pine nut dukkah can add flavor and texture to dishes like baba ganoush.

Stuffed Grape Leaves, Stuffed Cabbage Rolls or Stuffed bell peppers: Adding pin nuts to stuffed foods (especially when they are vegetarian recipes) adds a lovely texture flavor and nutritional/protein rich punch to the mix.

Tarts: Pine nuts pair well with honey in tarts. You can try making a pine nut and honey tart.

Pancakes: Take your pancake game to the next level by infusing them with pine nuts.

Sweet treats: Pine nuts combine well with figs in sweet treats like a fig and pine nut treacle galette.

Stuffed cabbage: You can add pine nuts to stuffed cabbage.

Korean pine nut noodle soup (Kalguksu).

Jatjuk: In Korea, pine nut porridge is called jatjuk and is often given to people recovering from illness.

Here are some tips for cooking with pine nuts:

Toasting pine nuts brings out their flavor. You can toast them in the oven, skillet, or microwave.

Pine nuts can be eaten raw, but most people who are allergic to other nuts are also allergic to pine nuts.

You can substitute blanched, slivered almonds for pine nuts in many recipes, but not for pesto.

Ground pine nuts can be used in baked goods and confections. You can make your own ground pine nuts in a food processor or spice grinder.

Species Profiles on the pine varieties listed above

Now I will offer a brief species profile on each of the species I listed below so that you can more effectively strategize for incorporating these noble and generous trees into your food forest designs in a way that is appropriate for your region and the scale of your project.

All of the species I cover below have edible needles, cones, seeds and pollen (with varying sizes for each species).

As the trees shed older needles they offer you a valuable resource that you can use to strategically acidify soil for growing nutrient dense crops like blueberries and mulching around shrubs that produce fruit low to the ground ensuring they do not have too much competition and the fruit stay intact until you pick them.

Through thoughtfully creating spaces for long lived evergreen species such as pine in our food forest designs we open up the potential for creating ideal spaces for long term outdoor medicinal and gourmet mushroom cultivation functions to be stacked into our food and medicine production. The year round partial shade provided by the species I list below can provide ideal protection for growing mushroom species (such as Shiitake, Lion’s Mane, Turkey Tail, Enoki, Reishi and Oyster on hardwood logs (which can be produced by other members of your food forest).

As you plan to incorporate these species into your design, I encourage you to not only imagine them in their mature form, but also to imagine all their life stages, and how you can stack functions throughout the time you will be tending to them as they grow. This opens up the potential for stacking functions through time and space. When they are younger you can selectively prune foliage for making medicine and tea and then as they mature you can prune some trees strategically so that some lower branches will be accessible for collecting pollen and seeds for eating while also allowing some trees to reach their full height and become important super canopy “Mother trees” in the distant future, providing nesting habitat for birds of prey, and providing a central foundation for protecting and building soil for countless other beings.

Think about how you might stack functions over years, and decades, growing things that naturally thrive in pine forests and mixed forests where pines are present, like blueberries, edible viburnums, lupins, bilberries, alpine strawberries and cloudberries.

These trees can become life long companions and teachers, noble, watchful and patient guardians that we can gift to future generations so that they may also receive the many gifts offered by these Nobles Of The Wood.

First up…

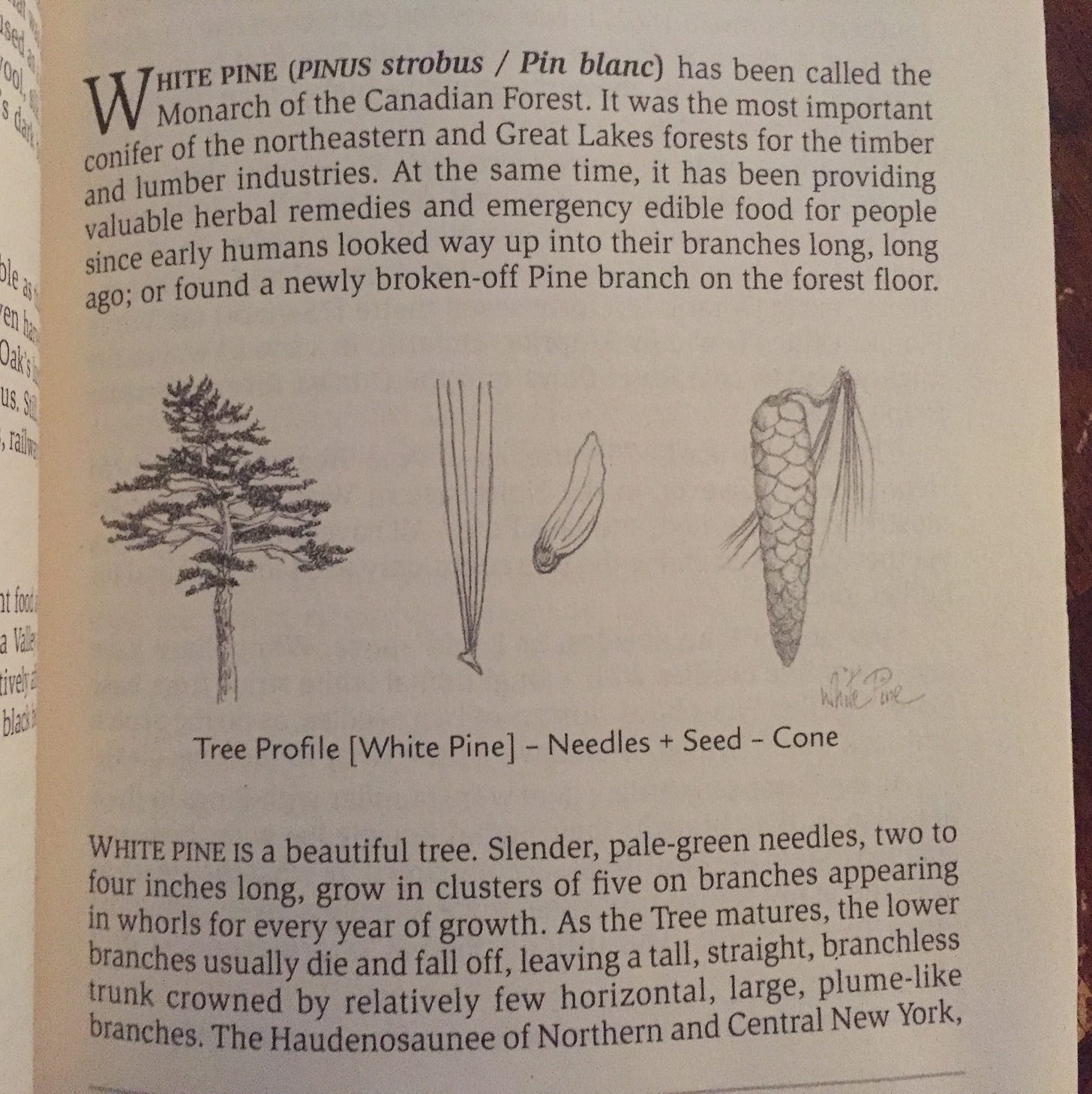

The Eastern White Pine (Pinus strobus)

Common Name: known as “zhingwaak” to the First Nation Ojibwe people of the Great Lakes area. Eastern White Pine is also referred to as the White Pine, Northern White Pine, Northern Pine, and Soft Pine. In Britain, this species is also called the Weymouth Pine – in honor of English explorer Captain George Weymouth, who took Eastern White Pine seeds to English from Maine in 1605. The Eastern White Pine is the state tree of both Maine (the Pine Tree State) and Michigan and the provincial tree of Ontario.

Cold Hardiness: 3 - 8

Longevity and growth form: 300- 450 years.

The Eastern White Pine is the largest eastern conifer, often growing up to 220 (and sometimes 240!) feet tall and up to 84 inches in diameter, depending on the soil. Michael Kudish lists a 275-year-old Eastern White Pine in Paul Smiths that was 49 inches in diameter.

The tallest (living) tree on record in New York State is an Eastern White Pine. This tree, which can be seen in the Elders Grove (also known as the 1675 grove) in Easy Street (near Paul Smiths in Franklin County), is 160.4 feet tall, with a circumference of 13.1 feet and a diameter of 50.1 inches. This tree is one of about fifty Eastern White Pines, most of which are 330 plus years old. Taller trees exist in older records, sadly, though they could have still lived today, they were all cut down for profit and for perpetuating the war racket (for british navy ship masts about 120 years ago).

Native Range:

After visiting Algonquin Provincial Park and hiking deep into the heart of the forest I found that the tree there that moved my heart the most was the Eastern White Pine (Pinus strobus).

White pines are magnificent trees that often tower above the already grand Sugar Maples in the forest here in the eastern forests of Canada (and the US). Standing tall and proud above their neighbors, they seem to be looking over the landscape with a watchful, protective eye.. lovingly reaching their inviting branches covered in soft needles out towards the horizon as if to say "Behold, this forest is my home, these fellow trees my revered family, we are a community that provides food, medicine, clean air and shelter for countless winged, four legged, finned and invertebrate sistren and brethren. We can provide for you too. We can prevent many serious illnesses that impact your species and all we ask is that you respect our family and give in return for what you take".

Habitat and Ecological Niche:

The Eastern White Pine is found in areas where the July temperature averages between 65 and 74 degrees. It can grow in a wide variety of soils, ranging from light, sandy soils to heavy, textured soils. The species is most frequently found on well-drained outwash soils, but is also present on well-trained tills. Eastern White Pine will also grow on imperfectly drained soils, but does poorly on the poorly drained sites. It is tolerant of drought, but cannot tolerate atmospheric pollution. The species is mid-tolerant to intolerant of shade; the tree must receive full sun at least for a good portion of the day.

Given these rather flexible requirements, Eastern White Pine flourishes in a wide variety of wet to dry habitats, including mixed wood forests, lowland conifer forests, and wetlands. It is frequently seen on the edges of lakes and ponds. Although it can be found in pure stands, this tree usually needs disturbances or openings to establish, and is therefore only a small component of the tree canopy in many forests.

Wildlife Value of the Eastern White Pine

Mammals: Red Squirrels are among the mammals which consume Eastern White Pine seeds.

The Eastern White Pine ranks among the very top plants in terms of its importance to wildlife. The tree is is valuable for both food and cover for a wide variety of mammals and birds, and its bark, buds, foliage, and cones, are consumed by a number of insects.

Mammals that eat the seeds, bark, and foliage of Eastern White Pine include American Black Bears, American Beavers, Snowshoe Hares, North American Porcupines, Gray Squirrels, and Eastern Cottontails.

With continuous change over time our perceptions of what habitat trees like Eastern White Pine provide have become increasingly divorced from historical realities – for wildlife species, this allows us to continuously chip away at habitat and be largely unaware of it. When we think of grizzly bears, we think of uninhabited mountain ranges with meadows and river valleys where humans rarely travel. But if we read history, we know that grizzly bears once inhabited the great plains and foothills of Canada and the United States, where the amount of prey alone (huge herds of bison along with deer and antelope) would indicate that the this habitat was far superior than the mountains to which the bears are now relegated. Humans eliminated the bears from these prime areas and so history has altered our perception of what high quality grizzly bear habitat really is.

White-footed Mice, Eastern Chipmunks, and Red Squirrels are the dominant mammal seed eaters. If you see large piles of stripped cones and cone scales at the base of a pine, it usually indicates a Red Squirrel midden, a term that refers to both the food cache and the debris that accumulates over months of stripping cones on a nearby log, branch, or stump.

Snowshoe Hares feed on the twigs, buds, and bark during the winter. The Martin/Zim/Nelson study (1951) estimates that these foods comprises 25 to 50% of the Snowshoe Hare's diet in winter in northern New York.

White-tailed Deer also consume Eastern White Pine, but only if little else is available. This species, like other pine species, is considered a starvation food in New York State.

Eastern White Pine is a common tree species in the breeding habitat of a wide variety of birds, including:

Species of songbirds that consume seeds of the Eastern White Pine include Yellow-bellied Sapsucker, Black-capped Chickadee, White-breasted Nuthatch, Pine Warbler, Pine Grosbeak, Red Crossbill, White-winged Crossbill, Evening Grosbeak, Red-breasted Nuthatch, and Pine Siskin.

Eastern White Pine is a common tree species in the breeding habitat of many Adirondack birds, including the colorful Blackburnian Warbler.

Eastern White Pines are used as nest sites by a number of birds, both year-round residents and summer migrants. Large pines are favored nesting sites for hawks and owls. Sharp-shinned Hawks and Cooper's Hawks usually place their nests on large branches next to the trunk. Broad-winged Hawks may build their nests in a crotch near the top of the tree. Great Horned Owls, Barred Owls, and Long-eared Owls reportedly adapt old hawk or crows nests for their own. Barred Owls often nest in trunk cavities and use the tree as a roost.

Eastern White Pines also provide nest sites for Boreal Chickadees, Orchard Orioles, Least Flycatchers, Blue Jays, Common Ravens, American Crows, and Common Grackles. Species which build nests on horizontal limbs or in branch foliage include Mourning Doves, Olive-sided Flycatchers, Magnolia Warblers, Yellow-rumped Warblers, Black-throated Green Warblers, Blackburnian Warblers, Bay-breasted Warblers, Pine Warblers, Evening Grosbeaks, Pine Grosbeaks, Purple Finches, and Pine Siskins. Pine needles are used as nest materials by several species of songbird, including Alder Flycatchers and Philadelphia Vireos.

Eastern White Pine is present in all successional stages. It is a pioneer species on old fields and other disturbed sites, reforesting abandoned fields, burned areas, and blowdowns. Eastern White Pines also become established after logging operations, particularly clearcuts. Eastern White Pine also functions as a long-lived successional species, and is a component of some climax forests throughout its range.

Characteristic companion shrubs include blueberries and Northern Wild Raisin.

in their native habitat you can often look on the forest floor for wildflowers such as Clintonia, Bunchberry, Wintergreen, Canada Mayflower, Starflower, and Cow-wheat, as well as Eastern Bracken Fern.

Mosses, such as Schreber's Big Red Stem Moss, and lichens may be common to abundant.

Here is a short video I recently recorded where I talk about the history of Eastern White Pine in Southern Ontario:

Old-growth forest was once abundant in the Ottawa valley, but the best growing conditions would have been in southern Ontario. While I was researching Ontario’s old-growth forests I found a description in the Canadian archives of a white pine that was cut from southern Ontario, a portion of which was displayed at the international exhibit of London in 1862. It was over 200 cm (7 feet) in diameter, 67 metres (20 stories) tall, and the first branch was more than 10 stories above the ground – higher than the tops of most pine trees today. The tallest white pine in Ontario today is only 47 metres tall, a little over two thirds the height of this historic tree. The 1862 pine contained enough wood to build six modern three-bedroom bungalows. Near the shores of Lake Erie the larger pines were reported to often reach 60 metres in height and over 7 feet in diameter.

The forest sites with the best soils and climate were long ago plowed under for farming, and generally remain as farmland to this day unless they have been paved over or built on. Average sizes for many of Ontario’s hardwoods would have been 37 to 40 metres in height and 80 to 90 cm in diameter – but they commonly grew larger. We have some anecdotal evidence of how large trees could grow given the best soils and climate – for example in his 1853 autobiography, Samuel Strickland describes a tree known as the Beverly Oak, in Cambridge Ontario. “I measured it as accurately as I could about six feet from the ground, and found the diameter to be as near eleven feet as possible, the trunk rising like a majestic column, towering upwards for sixty or seventy feet before branching off its mighty head.” Strickland measured other trees, such as an oak tree on his land that was 1.6 metres in diameter at a point 7.3 metres up the trunk, or a black cherry that was over one metre diameter and 15 meters to the first branch. Southern Ontario had old-growth forests that were much closer to west coast old-growth forest than we could imagine today, and there were consequences to clear cutting them.

What this multi-generational clearcutting and destruction of every single last climax/old growth expression of an entire species of tree has resulted in is something called “Generational amnesia”. It refers to how each generation considers how it first experienced a place as its true baseline, and any change that comes after it is abnormal or unnatural. Here in southern Ontario, I have experimented with asking about a hundred people that were born and raised here if they have ever visited a particular forest conservation area (which is an area that contains the very last un-logged primary old growth Carolinian Forest in this entire county). The result is that over 70% of them have never heard of the place (despite it being within 50 km of where they live). These people have never experienced the land and forests here as God intended them to be. They look at second growth (overcrowded, human manipulated and ecologically unbalanced places, such as Point Pelee, where the park staff spray round up to “control invasives” and there are no apex predators left to keep the numbers of deer down) as “normal”.

That kind of generational amnesia can create a sort of numbness, apathy and ecological illiteracy that cannot be addressed unless they actively seek out the last remaining patches of primary old growth forest that exist (here or elsewhere) and spend meaningful amounts of time in those forest ecosystems developing their pattern recognition faculties. Sadly, from what I have seen, in the era of digital addictions, materialism, 9-5 daily work grind and anthropocentrism, many of them are uninterested in doing so. Some of these people have never left the confines of southern Ontario and have no intention on doing so in the future. Through their total separation from any form of intact climax forest ecosystem from birth to adulthood, and their total lack of seeking to perceive anything else than the ecologically degraded landscape they are accustomed to, what this is resulting in is entire generations of human beings that see forests as nothing more an obstacles in the way of “sustainable development” and monoculture farming, or at best, they perceive forests places that we should preserve in the form of a weekend entertainment venue for humans, with parking lot like camping sites choking out the land, and a few scattered trees remaining as a sad memory of what once was. In essence, their plant blindness leads to a sort of impoverishment of the soul. That "plant blindness", leading to spiritual blindness is a serious issue that we must endeavor to remedy if we want our regenerative efforts to be able to stand the test of time.

One of the most significant species to go extinct due to the alteration of the eastern forests was the passenger pigeon. Numbering an estimate three to five billion individuals, passenger pigeons were once North America’s most numerous bird, moving in flocks that literally blocked the sun and took hours to pass overhead. The common narrative is that we hunted the passenger pigeon to extinction – but while hunting certainly tipped the species over the edge, it was primarily the destruction of eastern North America’s old-growth forests that caused the extinction of the passenger pigeon, by eliminating the large mast crops of nuts that were essential for successful breeding. As their habitat dwindled, passenger pigeons populations declined and were increasingly concentrated in small areas where hunting was easier.

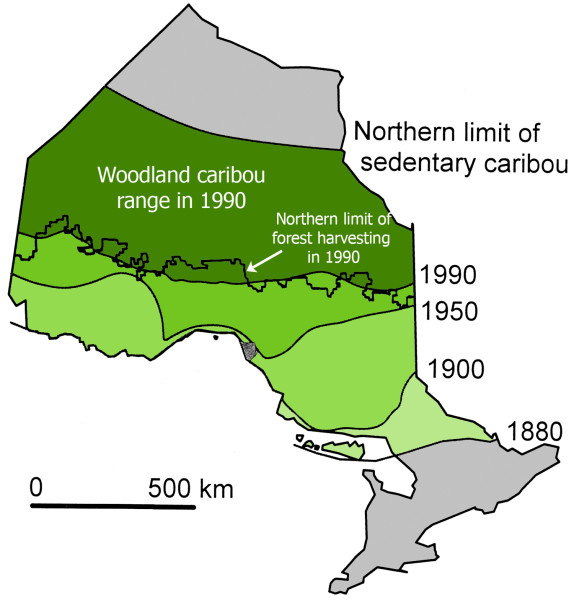

The passenger pigeon story is dramatic, but it is comfortably in the past. Today, however, we’ve seen severe and ongoing range declines in woodland caribou, and declines in American marten, and forest songbird populations, to name a few examples. These trouble us, but perhaps not as much as they should, because shifting baselines lull us into quiescence – for example we think of woodland caribou as being a far northern species, but caribou once ranged as far south as Algonquin Park. As the range continues to shrink, we think of caribou as something far away, not as a once-ubiquitous species being pushed ever closer to the brink. We know, thanks to the North American breeding bird survey, that songbird populations have been declining since at least the 1960’s when the survey began. Our knowledge of bird populations before the 1960’s is more limited, but the decline in songbirds is another example of an incremental decline that is hard for most people to perceive.

White Pines that towered high above the oaks, maples, hickory, basswood, walnut and other canopy trees in the forests of Ontario used to be common place (living 400 years plus and providing beauty and super canopy ecological roles in that ecosystem).

In a similar way to how my Gaelic indigenous ancestors of Ireland and Scotland had special laws and traditions that protected the elder rooted beings of the forest against human greed (and only cut one down after much deliberation, with an intent to use every bit of the tree and with a ceremony expressing gratitude for the gifts of the tree) the indigenous people of the Great Lakes region where I live now had safeguarded and ensured the flourishing of those towering giants for millennia (until the shortsighted, anthropocentrically motivated and greedy Europeans showed up that is).

As I documented in my in depth article on Shagbark Hickory, the most aggressive and arrogant deforestation of Southern Ontario (peaking in a clearcutting frenzy about 120 years ago) was in large part instigated and encouraged by the “Dominion of Canada” government putting out advertisements offering “free land” to anyone that would clear the forest, sell the old growth trees to the military for their ship masts and grow a monoculture annual crop on the land. The government propaganda conditioned settlers to view the forest as an “obstacle” and something that needed to be cleared to bring “order” to the land. One of the main motivations behind that push was to get people to do the dirty work of chopping down the 250-400 year old white pine to supply British with masts for the Navy to be able to perpetuate it’s war racketeering operations.

For more info:

For more info on ancient indigenous Ethnobotanical uses of this species:

For another great post on this species check out:

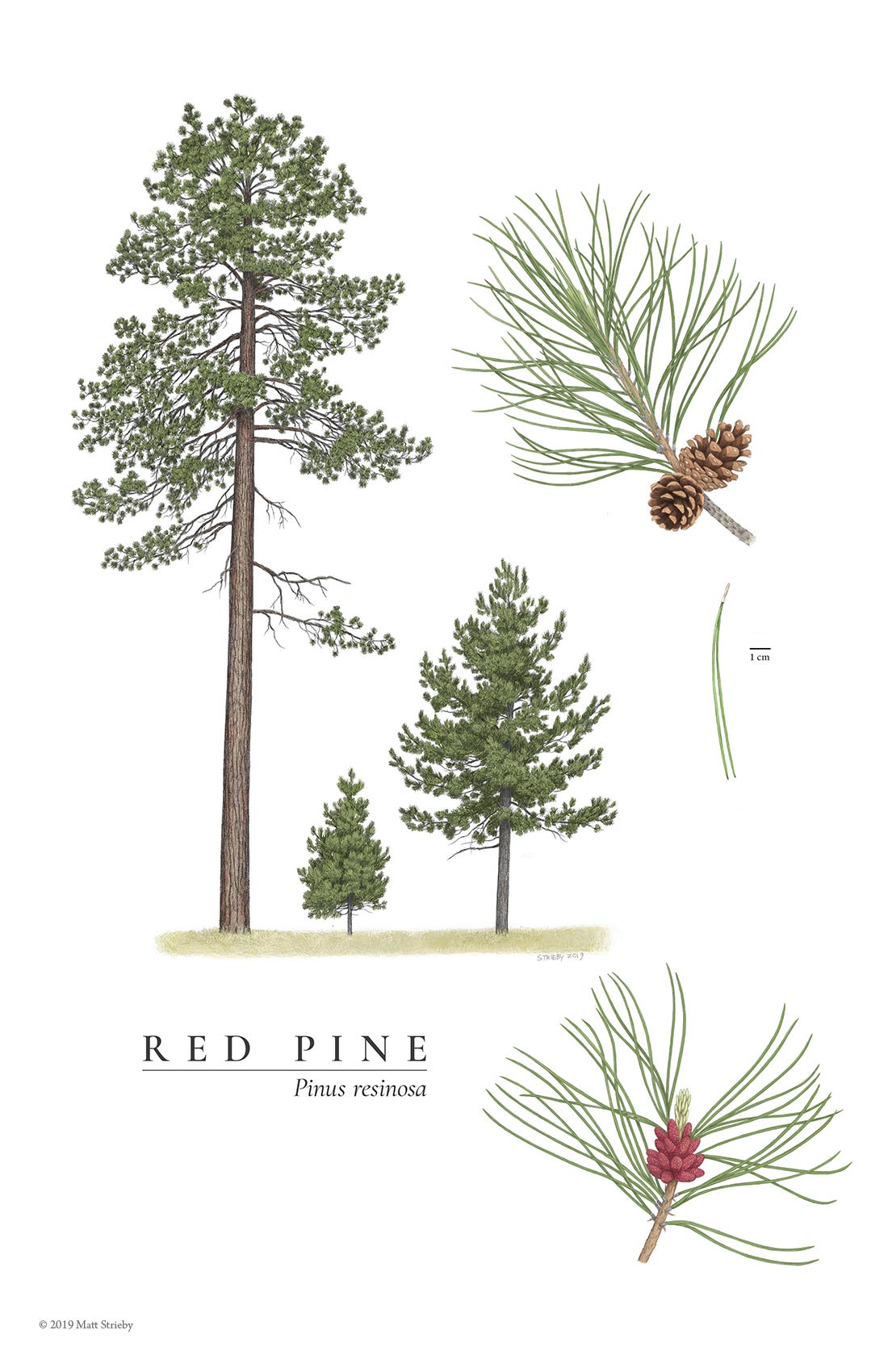

Red Pine (Pinus resinosa)

Cold Hardiness: 2–7

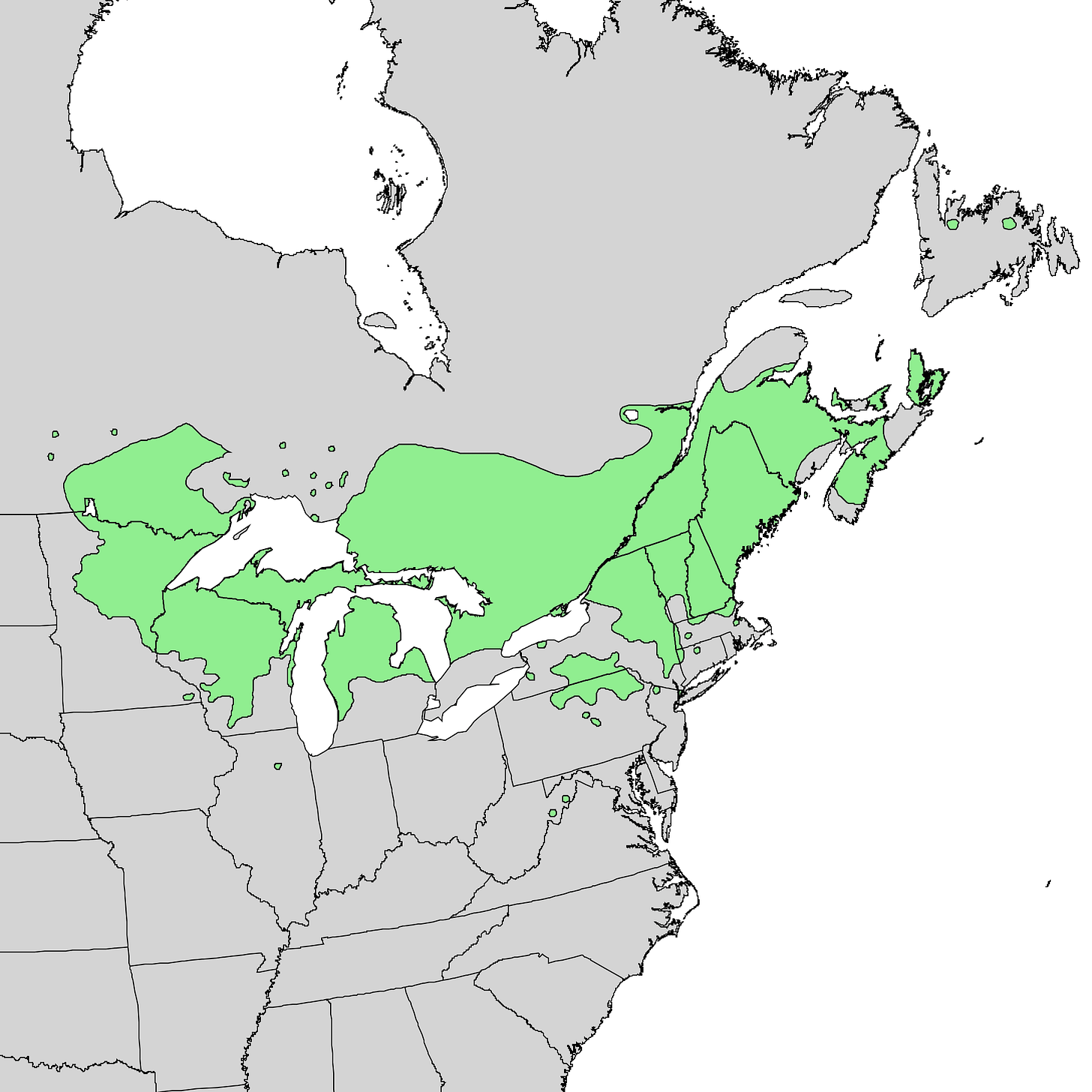

Native Range:

Longevity and growth form: Red pines can reach 500 years-old.

Red pine has an average height of 75 feet (23 m), but under ideal conditions (in other words, when greedy human do not chop them all down before they reach old age) they may grow as tall as 200 feet (50 m).

Habitat and Ecological Niche:

The ecological niche of the red pine (Pinus resinosa) includes:

Soil

Red pines grow best in well-drained, acidic, sandy to loamy sand soils with a pH of 5.2 to 6.5. They can tolerate a variety of moisture levels, including poor, rocky, and sandy soil. However, they are intolerant of high water tables and poor aeration.

Light

Red pines grow best in full sun, but can tolerate partial sun/shade. They are shade intolerant.

Fire

Red pines are fire resistant and typically limited to habitats that experience fire. They frequently colonize areas that have burned recently.

Wildlife

Red pines provide cover, nesting sites, and some food for many species of birds and animals. They attract songbirds, upland game birds, and mammals.

Competition

Red pines are often the dominant overstory species, but can also occur as an understory species with eastern white pine and/or jack pine. On more fertile soils such as loams, red pines are typically outcompeted by other species.

Location

Red pines are found in the deciduous and mixed forest zones, primarily in western Québec and across most of Ontario. They are also found in the USA in Minnesota, Wisconsin, Illinois, Michigan, West Virginia, Pennsylvania, New Jersey, New York, Connecticut, Massachusetts, Vermont, New Hampshire, and Maine.

For more info on ancient indigenous Ethnobotanical uses of this species:

Eastern Hemlock (Tsuga canadensis)

Cold Hardiness: 3-7

Native Range:

Longevity and growth form: at least 460 years. (A hemlock in Algonquin Park that is 408 years old is part of an unprotected forest licenced by the government for logging).

The government tells us that our tax money is used for Provincial Parks for the purpose of creating and maintaining a “protected area of land and/or water that's designated by a provincial government for several purposes, including: Nature protection, Historical preservation, Recreation, Tourism, and Education” yet that same government is still giving the greenlight for logging old growth within the park. This Orwellian Doublespeak and duplicitous greed must be called out for what it is and stopped immediately.

Read the full PDF report which the screenshots above are from here: https://www.oldgrowth.ca/wp-content/uploads/2020/02/prb6.pdf

Habitat and Ecological Niche:

The hemlock's shallow root system excels along riparian corridors, where the soil remains moist throughout the year. These shade-tolerant trees form dense canopies that provide cool refuge for fish and other wildlife. These trees are guardians of the quality of water, protecting and cleansing streams and ensuring our water table remains stable.

Habitat

Eastern hemlocks thrive in moist, shady areas, such as along waterways, in moist bottomlands, and on north-facing slopes. They are shade tolerant and can grow in a variety of soils, including shallow loams and silt loams over granite, gneiss, and slate bedrock.

Forest structure

Eastern hemlocks create a unique ecosystem by forming dense canopies that reach from the forest floor to the top of the tree. This structure provides a ladder-like habitat for wildlife, and creates microclimates that moderate temperatures and support a variety of plants and animals.

Water dynamics

Eastern hemlocks affect water dynamics in the forests they grow in by transpiring water year-round, especially in the spring. This helps regulate stream flow and water temperature, and improves water quality downstream.

Wildlife habitat

Eastern hemlocks provide food and shelter for many species, including deer, moose, ruffed grouse, wild turkey, black-throated green warblers, blackburnian warblers, and Acadian flycatchers.

EXTERNAL CHARACTERISTICS OF OLD EASTERN HEMLOCK TREES:

Large, old trees, logs and snags; unprotected Old-growth forests have significant biodiversity, genetic diversity, ecosystem services, recreational, educational and scientific values that can accumulate with stand age (Buchert et al. 1997, Mosseler et al. 2003a, Mosseler et al. 2003b, Luyssaert et al. 2008, Shaffer 2009). It is therefore useful to be able to identify old trees / old forests without necessarily using an increment borer. However, diameter is often a poor indicator of age in old-growth forests (Pederson 2010). For example, the three oldest trees in the Cayuga Lake Tract were also the three smallest. While current sample sizes is still too small for rigorous analysis, observations suggest the following for eastern hemlock.

• Eastern hemlock trees over approximately 200 years in age tend to have low trunk taper, and commonly have large upper branches.

• Eastern hemlock trees over approximately 300 years in age often have pronounced bark ridging in the upper 25% of the trunk and sometimes have pronounced curves and twists in upper branches, and/or high trunk sinuosity.

• Eastern hemlock trees growing with a combination of sun exposure and deep soil (lakeshores, some ridge locations) may have exaggerated old-age characteristics and be younger than they appear.

Significant old-growth forest remains unprotected in Algonquin Park, often rivalling (or even surpassing) the quality of forest singled out for protection in Algonquin Park’s system of nature reserves. Eastern hemlock forests are of particular concern because they are threatened across most of its range. It is alarming that forests exceeding 400 years in age are still available for logging in Algonquin Park, and that no effort has been made to identify and protect the Park’s remaining old-growth forests.

For info on the old growth Eastern Hemlock groves of the Laurel Highlands of PA, read:

For more info on specific ancient indigenous Ethnobotanical uses of this species:

Douglas Fir (Pseudotsuga menziesii)

When Douglas firs grow in dense forests, they self-prune their lower branches so the conical crown starts many stories above the ground. Trees growing in open habitats, especially younger trees, have branches much closer to the ground. Coast Douglas firs are the faster-growing and larger of the two varieties, and they commonly grow up to 250 feet (76 meters) in old-growth forests and can reach five to six feet (1.5 to 1.8 meters) in diameter. Rocky Mountain Douglas firs measure about the same in diameter but only grow up to 160 feet (49 meters).

Douglas firs were used by the indigenous people of Turtle Island for building, basketry, and medicinal purposes. Ailments that Douglas firs were used to cure include stomach aches, headaches, rheumatism, and the common cold.

Cold Hardiness: 4-6

Native Range:

The two Douglas fir varieties grow in very different habitats, as evidenced by their names. Rocky Mountain Douglas firs are the inland variety that grow in the mountainous Pacific Northwest and in the Rocky Mountains. They are much more tolerant of cold than the coast Douglas fir, which is suited to moist, mild climates on the west coast.

Longevity and growth form: 900- 1300 years

Douglas fir (Pseudotsuga menziesii) trees have a growth form that changes as they age, and their shape is influenced by a variety of factors:

Young trees: Have a narrowly conical crown that often extends to the ground.

Old trees: Have a short, columnar, flat-topped crown.

Individuality: As Douglas firs age, they develop a unique shape due to factors such as shading from other trees, storm damage, decay, and their specific growth environment.

Whorl-based growth: Douglas firs grow in whorls, which is a growth pattern common to many conifers.

Dead branches: Dead branches can remain on the trunk for years.

Branch loss: In denser forests, Douglas firs lose their lower branches as they grow taller, so the foliage can be high off the ground.

Douglas firs also have other characteristics, including:

Needles

Long, flat, spirally arranged needles that are yellow- or blue-green in color.

Cones

Hanging oblong cones with three-pointed bracts that protrude from the cone scales.

Bark

Thin, smooth, grey bark on young trees that becomes thick and corky on mature trees.

Fire resistance

The thick bark of mature Douglas firs makes them one of the most fire-resistant trees in the Pacific Northwest.

Habitat and Ecological Niche:

Douglas fir seeds provide food for a number of small mammals, including chipmunks, mice, shrews, and red squirrels. Bears eat the sap of these trees. Many songbirds eat the seeds right out of the cone, and raptors, like northern spotted owls, rely on old-growth forests of Douglas firs for cover. One species that relies on Douglas firs almost exclusively is the red tree vole. These tiny rodents seek cover in nests constructed in the crowns of Douglas firs and eat the needles. Red tree voles even obtain water from the tree by licking moisture off the needles. The largest coast Douglas firs commonly live to exceed 1,000 years (when humans are not chopping them down before they can fulfill their purpose). Rocky Mountain Douglas firs have a shorter lifespan, usually living no more than 400 years.

The ecological niche of Douglas fir trees includes a variety of roles in the environment and as a habitat for many species of plants and animals:

Biodiversity

Douglas fir forests are home to a wide range of plants, animals, and fungi.

Environmental services

Douglas fir forests help mitigate irratic weather patterns via initiating raindrop nucleation and slowing rain as it falls, improve air quality, and prevent erosion.

Food source

Douglas fir seeds are a food source for many small mammals, including chipmunks, shrews, and mice. The needles are eaten by the blue grouse in the spring, and black-tailed deer browse on new seedlings and saplings in the spring and summer.

Cover

Douglas fir forests provide cover for the northern spotted owl and other raptors. Red tree voles nest in the foliage of Douglas firs and eat the needles.

Habitat

Douglas fir forests are home to sensitive plant and animal species.

Climate

Douglas fir trees grow in a variety of climates, including cool temperate, boreal, and cool mesothermal. There are two main varieties of Douglas fir: the coast Douglas fir, which grows in moist, mild climates on the west coast, and the Rocky Mountain Douglas fir, which grows in the Rocky Mountains and the mountainous Pacific Northwest.

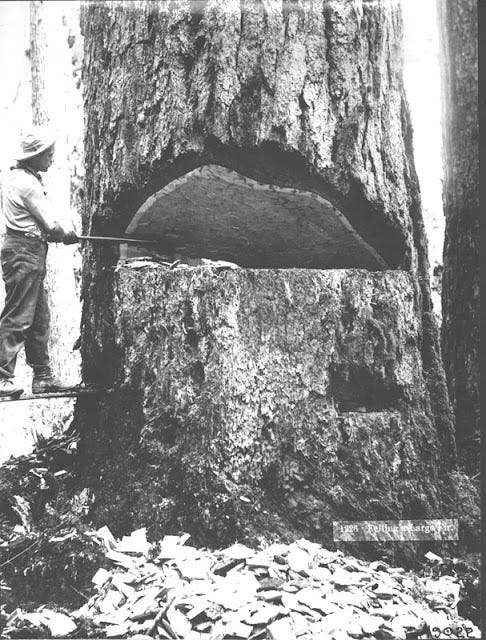

Relentless human greed and ignorance has led to scenes like the image shown below becoming the norm in the last remaining patches of old growth habitat for these majestic trees.

“How Tall Can Douglas-fir Get?

Although a Coast redwood is presently the tallest tree found to date, there is evidence that the coastal Douglas-fir has the biological capacity to surpass the redwoods in stratospheric height. Once trees reach the limit beyond which water can no longer be pumped to the top, the leader experiences 'drought stress' and dies off.

"In 2008, a study proposed that the maximum height for a Douglas fir -- one of the world's tallest trees -- is about 453 feet (138 meters)." [source]

A Douglas-fir is the third tallest tree in the world (or second, depending on other accounts), and some believe a Douglas-fir could be, or once was, the tallest. Upper height limit estimates for the species go as high as 476 ft, and before logging began in the 19th and 20th centuries, plus 400 foot trees were probably fairly common.

Historical Accounts Of 400 Foot Douglas-fir

Some accounts of the tallest of the tall may be loggers' tales, but others are documented measurements.

You can read a post here where the author discussed 400 ft plus Douglas-fir trees. An informed reader posted a couple of comments in response. They contain information regarding the historical heights once attained by the king of the Pacific Coast Forest, the Douglas-fir.

See comments below photo.

Industrial logging has removed most of the tallest Douglas-fir, historical photo, Washington

Reader Comments Regarding Tall Douglas-fir

"A Douglas fir measured 415 feet high, (127 meters) in 1902 at the Alfred John Nye property in Lynn Valley. Diameter was 14 ft 3 inches 5 feet from the ground.

A 352 footer was felled in 1907 in Lynn Valley. Diameter was 10 feet.

In 1897 a 465 foot (142 m) Douglas fir was felled in Whatcom, Washington on the Alfred Loop ranch near MT. Baker. Diameter was 11 feet, and 220 feet to first branch. Board footage was 96,345 feet of top quality lumber.

A 400 footer was felled in 1896 at Kerrisdale, BC, sent to Hastings mill. J. M. Fromme measured the giant at 13 ft 8 in diameter.

Records of even taller fir trees exist, but I am in the process of collecting a complete and up to date list of old champions long forgotten."

And a follow-up comment:

"They measured a Redwood tree near the Oregon border in 2006, it is 115.6 m tall above average ground level, but to the lowest end of the trunk it's about 117.6 m total height.

Michael Taylor, Chris Atkins, and Mario Vaden, are the top guys searching the forests for new tallest tree species. They just located last week a new record Douglas fir west of Roseberg, Oregon it is 98.3 meters tall, live growing top. They're hoping to find a monster fir over 100 meters, and I think they will. Thousands of hectares of Oregon forest is relatively unexplored.

But sadly, over 90% of the really big old growth has been cut down in the North West, so finding a 120 meter fir is unlikely -- Not impossible though.

I posted the list in a wikipedia talk section, titled, "Historically Reported Douglas-Fir Exceeding 300 and 400 Feet." I also made a couple experimental Youtube videos dealing with the super tall reports, the 400 foot and up class."

Is it possible that the Coast redwood is not the tallest tree species on earth?” (source)

The very last stands of an intact watershed composed of one thousand year old plus Douglas Fir (and Western Cedar) trees are under threat by corporate and government corruption in BC, Canada, you can learn more about that situation here:

Death By A Thousand Clearcuts

“Those who contemplate the beauty of the earth find reserves of strength that will endure as long as life lasts. There is something infinitely healing in the repeated refrains of nature — the assurance that dawn comes after nig…

and here:

For more info on ancient indigenous Ethnobotanical uses of this species:

http://naeb.brit.org/uses/search/?string=Pseudotsuga+menziesii

https://phytochem.nal.usda.gov/ethnobotanical-plant-pseudotsuga-menziesi

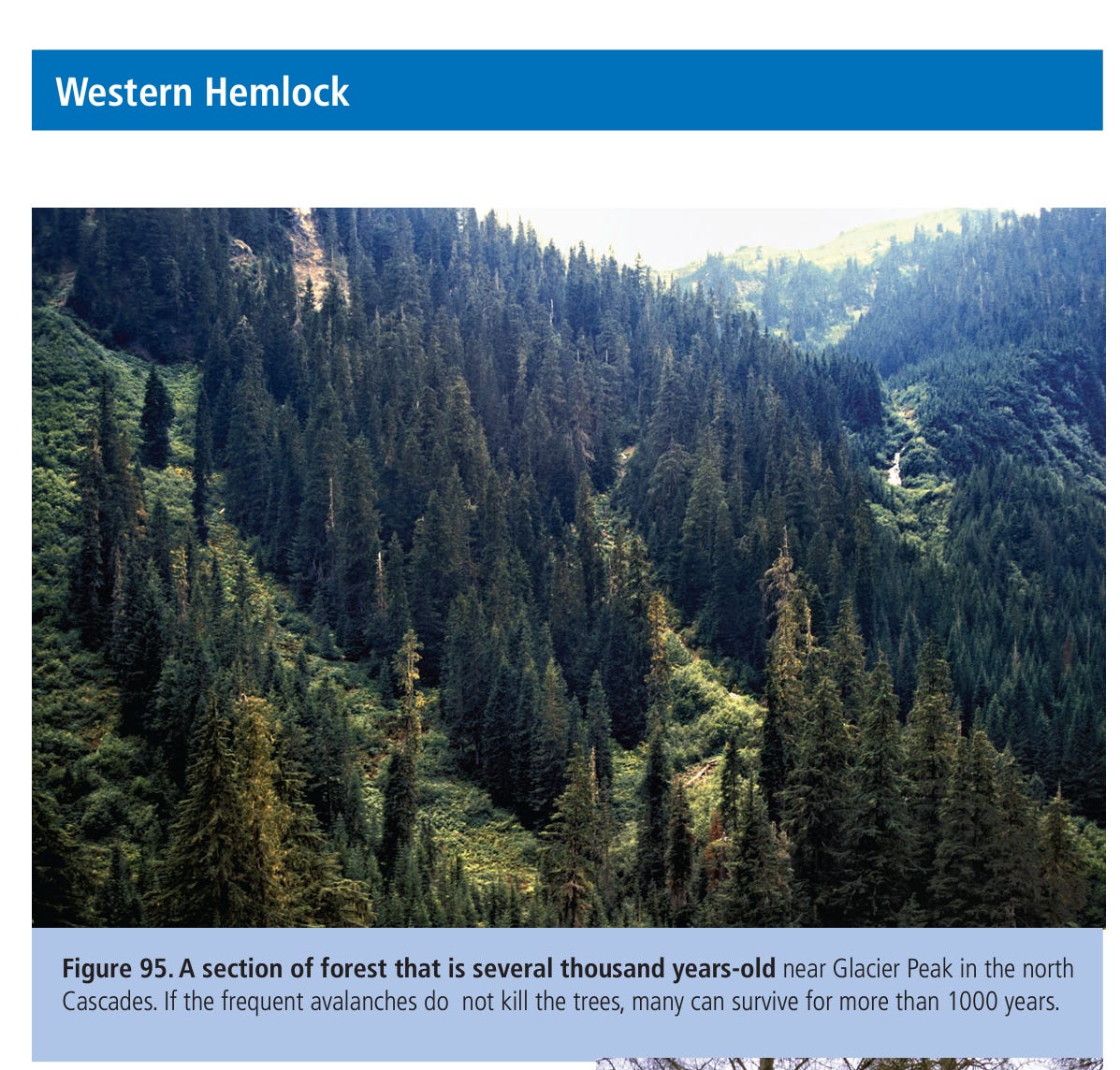

Western Hemlock (Tsuga heterophylla)

As one of the most shade-tolerant tree species, western hemlock is prevalent in nearly all of the few old forests left in Washington and BC. Although it is often overlooked when growing with its much larger associates – Douglas fir, Sitka spruce, or western redcedar – western hemlock can occasionally reach impressive dimensions. It has been recorded to 78.0 m tall, 290 cm in diameter, and with a volume of 121 m3. Even though it only represents a fraction of the wood volume in old growth forests, it nearly always represents more than half of the foliage (Figure 83). Accordingly, western hemlock controls the understory light environment in these old stands. A mature hemlock tree casts a very dense shade, only allowing shade-tolerant plants to persist.

Cold Hardiness: 4-6

Native Range:

Longevity and growth form: 800 - 1200 years

Western hemlock is a large evergreen conifer growing to 50–70 metres (165–230 feet) tall, exceptionally 83 m (273 ft), and with a trunk diameter of up to 2.7 m (9 ft).

The western hemlock (Tsuga heterophylla) has a broad, conical crown when young, and becomes cylindrical in older trees:

Crown

When young, the crown is broad and conic with a drooping leader shoot. In older trees, the crown becomes cylindrical and may have no branches in the lowest 30–40 meters.

Branches

Most branches sweep down.

Bark

The bark is smooth when young, and becomes dark reddish-brown, thick, and strongly grooved with age.

Needles

The needles are short stalked, flat, finely toothed, and of unequal length. They are dark green to blue grayish-green.

Seed cones

The seed cones are ovoid, short-stalked, brown, with many thin papery scales. They hang down at the end of the twigs.

Habitat and Ecological Niche:

The western hemlock (Tsuga heterophylla) has a diverse ecological niche that includes providing food and shelter for many wildlife species.

Food and shelter: Western hemlock provides food and shelter for many animals and birds, including:

Deer and elk: Browse the leaves

Snowshoe hares and rabbits: Eat the seedlings

Deer mice and small birds: Eat the seeds

Northern spotted owl: Found in forests with western hemlock and Douglas-fir

Northern flying squirrel and red tree vole: Live in western hemlock forests

Yellow-bellied sapsucker and northern three-toed woodpecker: Use the trees for nesting

Old-growth western hemlock forests are threatened, and only a small percentage are protected:

Coastal Western Hemlock (CWH) zone is a unique ecosystem that stretches along the north Pacific coast of North America, including most of coastal British Columbia (BC). However, only 2% of CWH ecosystems in the Salish Sea region are protected

For more info on ancient indigenous Ethnobotanical uses of this species:

https://phytochem.nal.usda.gov/ethnobotanical-plant-tsuga-heterophylla

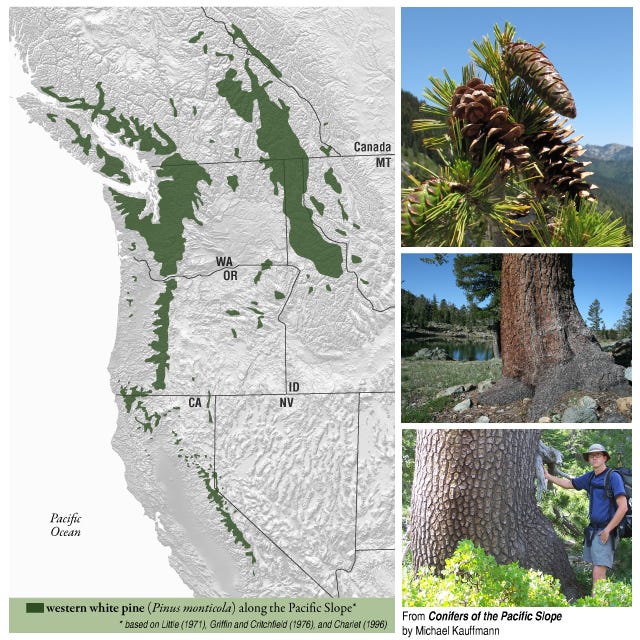

Western White Pine (Pinus monticola)

If ever a tree loved to live in the mountains, it's the western white pine. You'll find it getting along quite happily in the high country of California, Idaho, Montana, Oregon, Washington, and British Columbia.

It occurs in mountain ranges of northwestern North America. It is the state tree of Idaho and is sometimes known as the Idaho pine.

Cold Hardiness: 1-7

Native Range: Western white pine occurs in the Pacific Northwest. The northern boundary of its range is at Quesnel Lake, British Columbia, latitude 52 deg. 30 min. N., and the southern boundary is at Tulare County, California, latitude 35 deg.

Longevity and growth form: 400- 600 years

This 45-150 ft., sometimes taller, evergreen forms a slender crown in thick stands or becomes more open and spreading when exposed. Branchlets are stout, bearing soft-textured, blue-green needles in groups of five. Bark is gray and smooth at first, becoming checked with flaking scales.

Habitat and Ecological Niche:

Soil

Grows well in moist, well-drained, acidic soils, and in calcium-rich soils. It can also grow in poor, rocky soils. However, it doesn't grow well in very acidic peat bogs.

Elevation

Can be found at elevations of 600 to 3,100 meters (2,000 to 10,200 ft) above sea level.

Sunlight

Grows best in full sun.

Forest types

Often occurs in forests with fir and hemlock species, especially those that tolerate shade.

Disturbances

Benefits from disturbances that clear away competing species, including low fires that don't destroy all of its cone-protected seeds.

For more info on ancient indigenous Ethnobotanical uses of this species:

Scot's Pine aka “Baltic pine” (Pinus sylvestris)

Spots pine is a species of tree in the pine family Pinaceae that is native to Eurasia, ranging from Western Europe to Eastern Siberia, south to the Caucasus Mountains and Anatolia, and north to well inside the Arctic Circle in Fennoscandia.

Interesting Facts about the Scots Pine Tree:

They are among the oldest living organisms in Ireland and have witnessed centuries of history and environmental change.

Ecosystem Engineer: Scots Pine trees play a key role in shaping and maintaining forest ecosystems. They provide habitat and food for a wide range of wildlife species, contribute to soil stabilisation and nutrient cycling, and help regulate local climate and hydrology.

Fire Adaptation: Scots Pine trees are adapted to survive and even benefit from wildfires. Their thick, fire-resistant bark helps protect the cambium layer from heat and flames, allowing the tree to recover and regenerate after a fire. Additionally, some Scots Pine cones require the heat of a fire to open and release their seeds, promoting new growth and regeneration in fire-adapted ecosystems.

For more pics of this seedling that I grew from the seeds in the other pic above and his little brothers check out: https://archive.org/details/scotspine This little guy is now about a foot tall and three of his brothers are doing well at about 9 inches tall as well. Symbolism: Scots Pine trees have cultural and symbolic significance in Celtic, Norse, and other European traditions. They have been associated with strength, resilience, and longevity, and have been used as symbols of national identity and pride in Scotland and other countries where they are native.

Longevity and growth form: This species can grow up to 35m in height and can live for up to 700 years. He would have been known to my ancient Celtic ancestors for his medicinal gifts and was a symbol of durability, as in the Gaelic proverb:

Cruaidh mar am fraoch, buan mar an giuthas (Hard as the heather, lasting as the pine)

Native Range:

The native range of the Scots pine (Pinus sylvestris) includes:

Scotland

Scandinavia, excluding Denmark

Northern Europe

Northern Asia, extending to the Caucasus Mountains and the Okhotsk Sea in eastern Siberia

The Mediterranean

The Scots pine is the most widely distributed pine in the world, and can grow from sea level to about 8,000 ft.

The Scots pine was introduced to North America and is now naturalized in the Northeast and Great Lakes states. In Ontario, it was imported in the early 1900s to help stabilize soil on abandoned agricultural lands. It's now a significant component of many forests in southern Ontario.

The Scots pine is a keystone species in the Caledonian Forest, where it was once the largest and longest-lived tree. However, the forest has declined due to overgrazing and clearcutting for profit.

Habitat and Ecological Niche:

The Scots pine (Pinus sylvestris) plays a critical role in the ecosystems it inhabits as a keystone species:

Habitat

The Scots pine provides food and shelter for a wide range of wildlife, including birds, mammals, insects, and other organisms. For example, the tree's bark provides shelter for insects, while its needles are eaten by caterpillars. Birds eat the insects and seeds, while squirrels and mice cache the seeds. The Scots pine also provides nesting sites for songbirds and cover for other birds.

Soil stabilization

The Scots pine's extensive root system helps stabilize soil, prevent erosion, and improve soil structure.

Nutrient cycling

The Scots pine absorbs carbon dioxide from the atmosphere and releases oxygen through photosynthesis. It also cycles nutrients through its needles, branches, and roots, contributing to soil fertility.

Lichens grow on the bark and branches of the Scots pine, especially in wet areas. These lichens fix nitrogen from the air, which is then absorbed by the soil when the lichen decays.

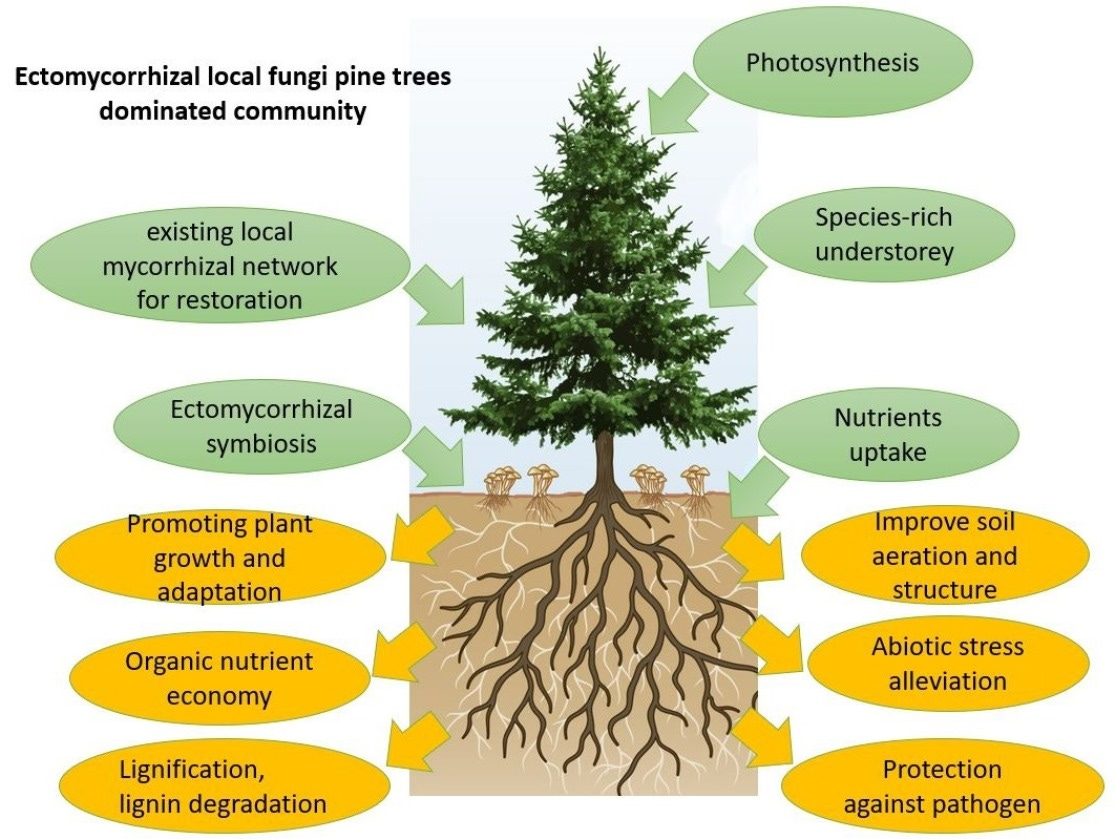

Mycorrhizal associations

The Scots pine has a special relationship with fungi, where the fungi's threadlike filaments wrap around the tree's root tips, exchanging nutrients.

For more info on ancient indigenous Ethnobotanical uses of this species:

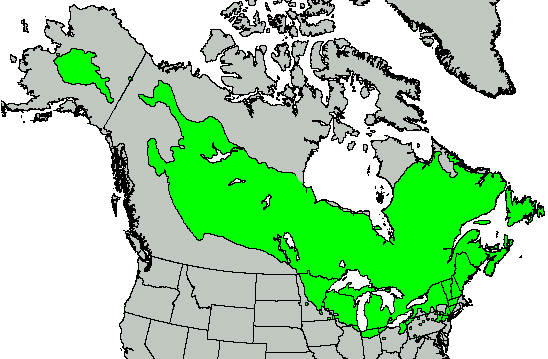

Tamarack aka “Larch” (Larix laricina)

Tamarack (or Larch) is known as “The Medicine Woman” tree to some, she is the protector and purifier of our sacred waters, the medicine provider, the golden glowing one and the soft and delicate one.

The way her soft needles reach out in all directions absorbing the sunlight and then turning her needles the bright color of the golden sun in the autumn, the way she grows along the lake shores, in the peat pogs and beside the babbling brook and the alpine flower fields reminds me of our connection to the celestial beings above (known as “stars”) and our connection the water that breaths life into these bodies we inhabit.

This ancient medicine woman protects the mountain sides, the lake shores, the peat bogs and the arctic tundra. She is resilient and provides many gifts to those who take the time to pay attention and respectfully receive the gifts she shares.

Cold Hardiness: 1-7

Native Range:

The native ranges of different types of larch include:

Western larch

Native to the western United States and Canada, including southeastern British Columbia, western Montana, northern Oregon, and Idaho. It grows in the Columbia River drainage, from the Cascade Range to the Continental Divide. Western larch can grow up to 200 feet tall, and can survive in temperatures as low as −50 °C (−58 °F).

Eastern larch

Native to eastern Canada, Alaska, and the northeast United States, including the Great Lake states and northern Minnesota. It can grow in dry upland soils, or in wet peaty soils like bogs and swamps.

Subalpine larch

Native to northwestern North America, including the Rocky Mountains of Idaho, Montana, British Columbia, and Alberta. It can grow at high altitudes, from 1,500 to 2,900 meters (4,900 to 9,500 ft). It can survive in low temperatures and on thin rocky soils.

Longevity and growth form: 300- 2600 years

Habitat and Ecological Niche:

Below an excerpt from Arboretum Borealis: A Lifeline of the Planet

species of larch are native to Canada, from eastern Yukon and Inuvik, Northwest Territories east to Newfoundland, and also south into the upper northeastern United States from Minnesota to Cranesville Swamp, West Virginia; there is also an isolated population in central Alaska. The word akemantak is an Algonquian name for the species and means "wood used for snowshoes".

The following is an excerpt from Plants Have So Much to Give Us, All We Have to Do Is Ask : Anishinaabe Botanical Teachings

Next an excerpt from The Healing Trees : The edible and herbal qualities of Northeastern Woodland Trees

by Robbie Anderman

For more info on ancient indigenous Ethnobotanical uses of this species: