Oak - nurturers, protectors and sovereign kings of the forest

Installment #23 of the (Stacking Functions in the Garden, Food Forest and Medicine Cabinet : The Regenerative Way From Seed To Apothecary series.

This post serves as the 23erd post which is both part of the (Stacking Functions in the Garden, Food Forest and Medicine Cabinet : The Regenerative Way From Seed To Apothecary series).

“The creation of a thousand forests is in one acorn”

- Ralph Waldo Emerson

The acorn is the embodiment of life potential. A seed that sprouts future forests and a food that sustains its inhabitants (and even the inhabitants of the ocean). Acorns beckon our relationship with the natural world, and today they encourage the ‘rewilding’ of humankind.

Oaks are keystone species, meaning that the whole web of life is disproportionately dependent on them in the regions they reign. If the oaks suffer, everyone suffers. If the oaks are happy, everyone is happy.

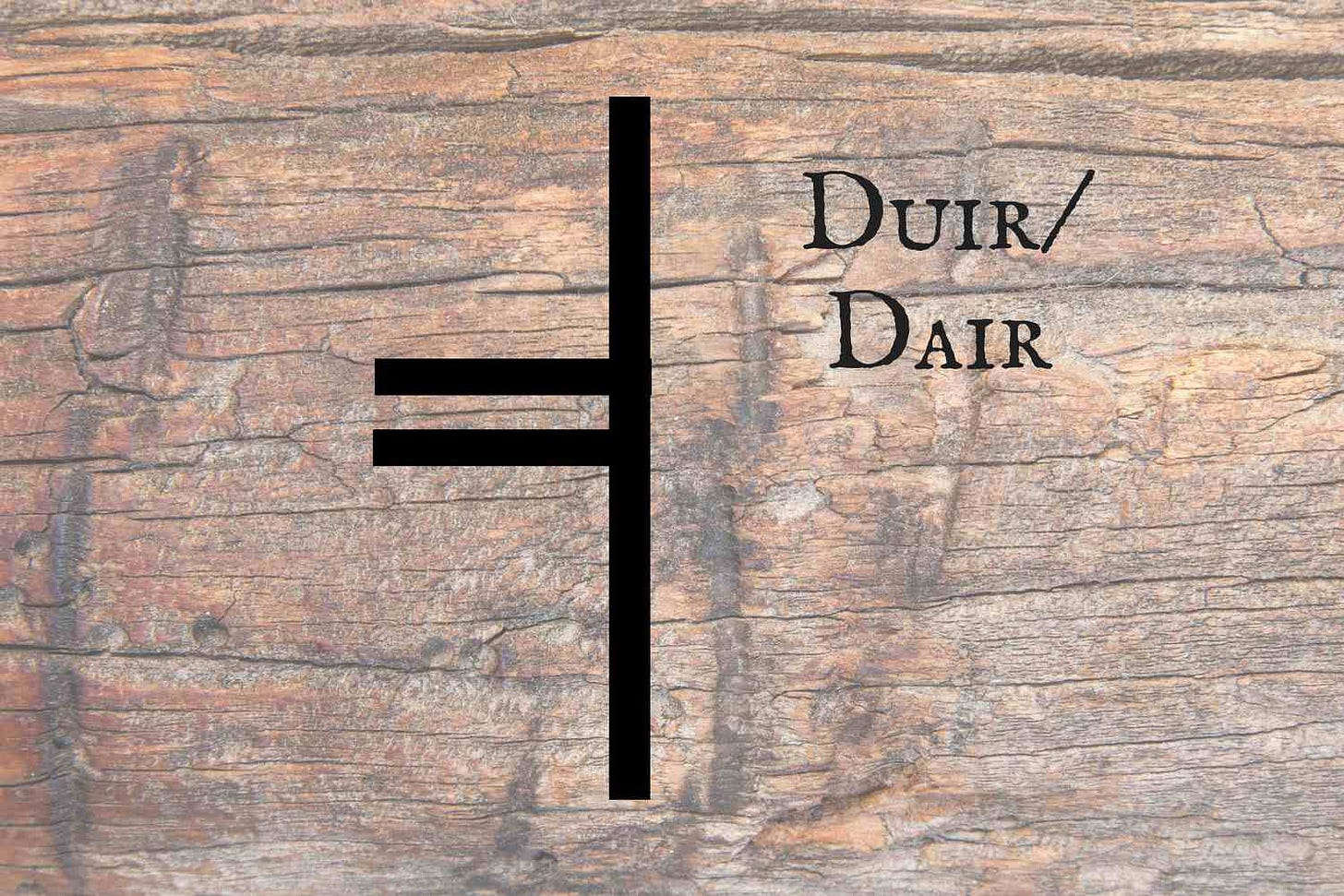

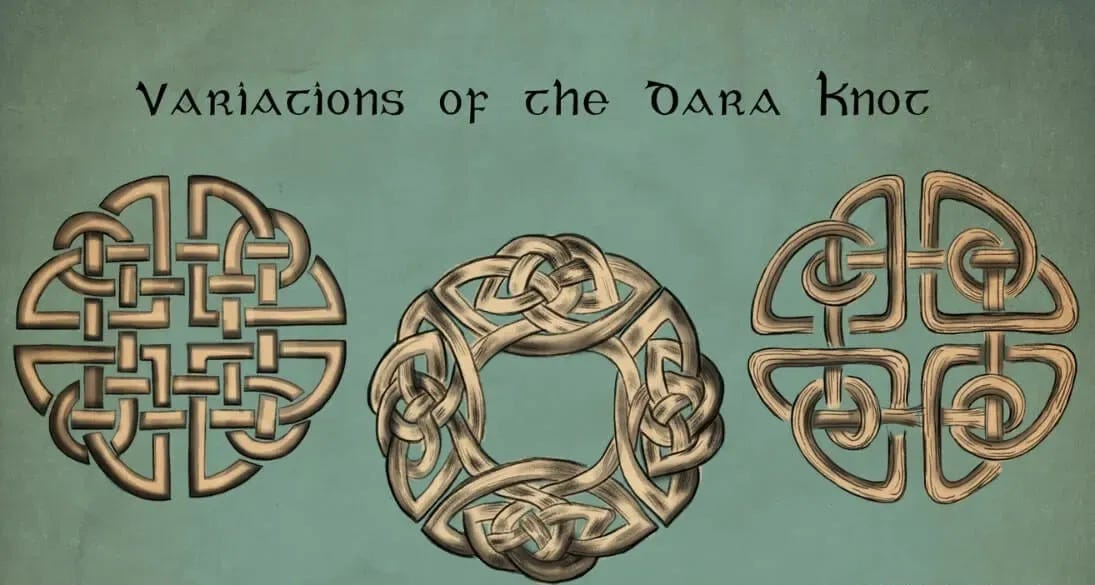

This tree was sacred to my ancestors of Éire and Albion. My Gaelic ancestors referred to these resilient, generous and noble tall rooted beings as ‘Darach’ (in Scots Gaelic). However, there are other Gaelic words to describe an Oak, such as ‘Dair’ or ‘Duir’ which come from the more ancient Ogham (OH-am) alphabet.

Ogham was predominantly used to write the early Irish language and from the 5th century was used in the Gaelic Kingdom of Dalriada covering what is now Argyll, West Lochaber and the Inner Hebrides as well as the northern tip of Ireland.

Oaks are revered globally by myriad cultures that recognized their sacred gifts, their fortitude, grace and the wisdom these beings offer our human family. This is for a good reason, as oaks are Keystone species that send out trophic cascading ripple effects of increased biodiversity into the places they grow. These are Mother Trees.

(FYI: Throughout this article I will use terms like “Mother Tree” and “King of the forest” in reference to the Oak interchangeably. This may appear contradictory at first glance, but that is only when we look at these beings from an anthropomorphic perspective. Humans have very definitive genders as natural individual beings. Oaks, on the other hand, are beings that both stand strong, as protectors, creative, expansive and pollinating beings as well as being nurturing, receptive, patient and wise beings that foster new life in embryos called acorns, thus, these beings embody both archetypes of the Divine Masculine and Feminine)

Oak trees are fountains of life that provide a home for countless insects, winged beings, shelter for amphibians and essential fatty acids to support robust mammalian populations. Oaks become a pillar that can support a forest ecosystem to unfold into resplendent expressions of vast biodiversity in fungi, deep soil life and multitudes of four legged mammals that nurture their young from the nourishment these trees provide (yes they are Mother Trees in the truest sense).

Acorns are an abundant wild food source around the world, and a single tree can produce more than 2,000 pounds of nuts. Rich in calories and micronutrients, eating acorns was once a part of life for humans everywhere that oaks grow.

Up to 2300 species are known to be associated with oak, and that doesn’t include all of the fungi, or any of the bacteria and other microorganisms which create a symbiotic home with the oak.

The 2300 species consist of some 38 bird species, 229 bryophytes, 108 fungi, 1178 invertebrates, 716 lichens, and 31 mammals. Of these species, 320 are found only on oak trees, and a further 229 species are rarely found on species other than oak.

While human monarchs are historically mostly tyrants, Oak trees are beings that embrace the role of a sovereign monarch with patience, benevolence and magnanimity.

“A true sovereign does not run in fear from life or from death. A true sovereign does not dominate and conquer (that is a shadow archetype, the Tyrant). The true sovereign serves the people, serves life, and respects the sovereignty of all people.”

- Charles Eisenstein

Those at the material pinnacle of human societies may fail miserably to embrace the archetype of a true sovereign monarch described above, but I would argue that the mighty Oak stands tall and true where humanity has yet to succeed.

The Oak protects, nurtures, supports, guides the development of ecosystems, shaping and overseeing the continued thriving of entire communities of human and non-human life. The truest (and perhaps never before seen in human society) expression of the archetype of a sovereign monarch.

These trees are such abundant providers of food, inspiration for art and spiritual wisdom that entire cultures in the past were defined by their strong symbiotic relationship with the oak tree.

The word balanoculture is the offspring of a mixed marriage between Greek βάλανος (bálanos = acorn) and Latin cultura. It means a society in which the collection, storage, preparation, and consumption of acorns as a foodstuff play a large role.

“Balanocultures were among the most stable and affluent cultures the human world has ever known.”

-William Bryant Logan in “Oak: the Frame of Civilization”

A balanoculture basically means an economy based on acorns. Many proto-agricultural societies around the world practiced balanoculture like the Greeks, Druids, the Takilma, the Wendat and Shasta (among many others).

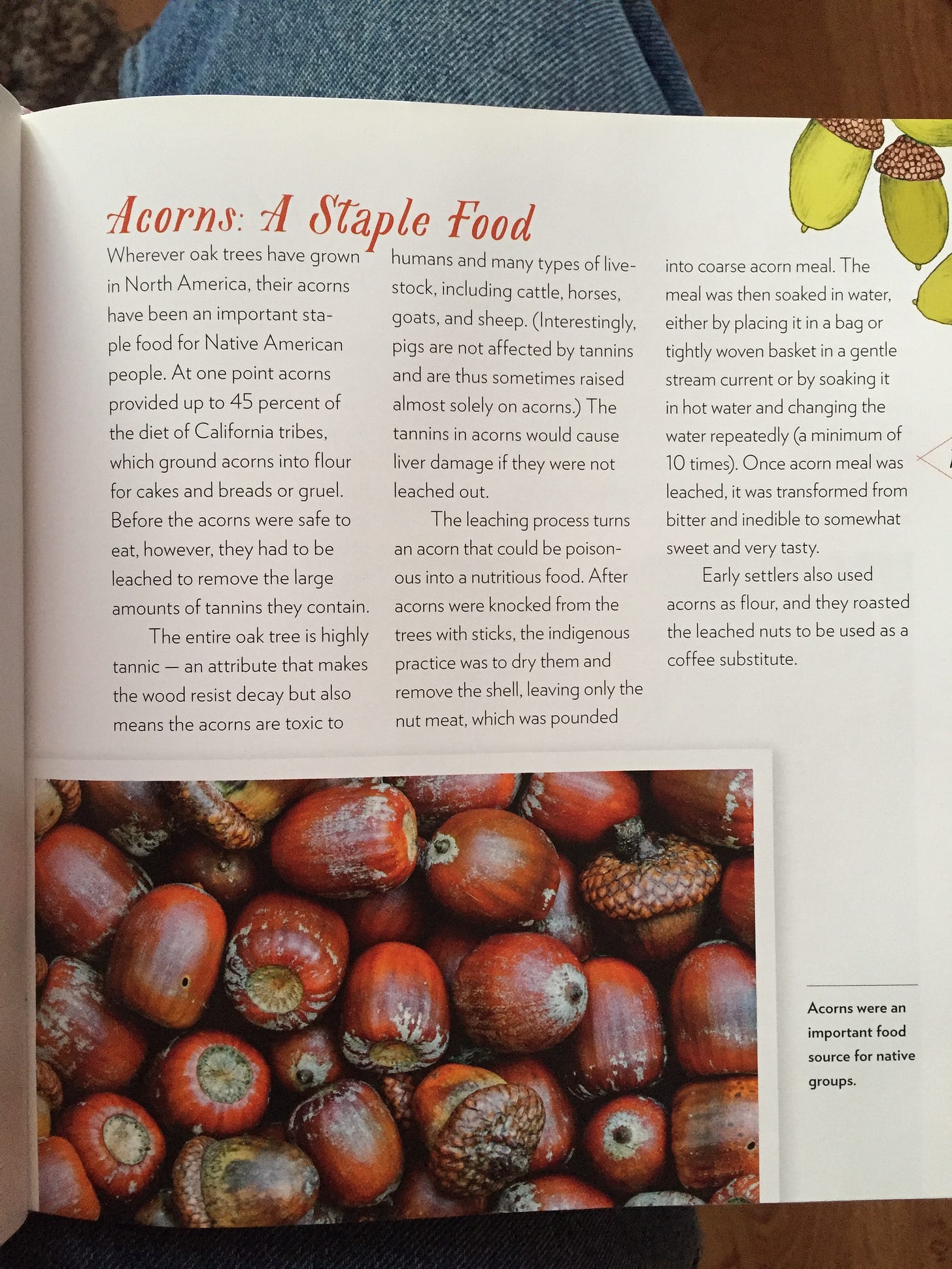

‘Balanophagy is the practice of eating acorns. Acorns are more than just food for birds, squirrels, and hogs. They have been used for food by millions of humans over the ages. Acorns compare favorably in nutrition with common grains, though acorns contain more fat. (That was not a bad thing during most of human history.) If you have any ancestry among people of the northern hemisphere, there is a reasonable chance that you have some ancestors who ate acorns.’ – Kelli Kallenborn

In a similar way to what I described in my articles on Birch trees as well as Pine trees, this ancient tree family is found in almost the entire Northern Hemisphere, meaning that the Oak tree is one of those tethers to the ancient indigenous histories of all people who have ancestors that called the northern hemisphere home. In fact, for those of us in the northern hemisphere, I would agree with Kelli Kallenborn’s statement above in saying that each and every one of our respective ancestors had a close relationship with at least one type of Oak tree and that it played an integral part in their daily life, their traditions and their means for surviving.

Thus, the tall rooted elder beings of the Oak family offer a sacred reminder of a time before arbitrary lines were drawn in the sand by statists for greed and ego back to an era when many of our ancient ancestors knew the trees intimately and had a reciprocal relationship with them. Long before people were swearing allegiance to kings, queens and flags they were swearing allegiance to the living Earth and recognizing our ancient kin (such as these Kings Of The Forest we know as Oaks) and the many gifts they shared with us.

If your ancestors hail from the northern hemisphere Oak trees offer you a sort of universal language to perceive the common ground you share with the ancestors of those now residing in nation states far and wide. This tree offers you a glimpse into your own indigeneity and your ancestors relationship to place. Yes all of us have an indigenous past connected to our blood and our soul. For some of us, that indigeneity is buried under multiple millennia of bloodshed, oppression, re-writing of history and statist propaganda. Though it may be buried deep and many may have sought to erase that part of your heritage from the stories of modern cultures, this part of you exists nevertheless. This part of your ancient heritage when your ancestors lived close to the land and the forest, recognizing more than human beings as deserving of our respect as conscious beings.

After you read the article below and learn about all the beauty, blessings and the many gifts offered to us by Oak trees I invite you to take a moment next time you see one to touch his bark, pick up his acorns, smell his foliage as you look upon him with gratitude and reverence for all that he shares with the world you will be choosing to see the world through the eyes of your ancient ancestors.

Through seeing trees like Oak as those whose blood flows in your veins now did millennia ago you begin the unlearn the lies, self important delusions and separation mentality that is inherent in modern civilization. In that act to see the noble Oak tree with the understanding and reverence of those who came before you and walked the earth with respect eons ago, you are building a tangible bridge that connects you to your honoured elders and ancestors and a bridge that also directs you towards a more Regenerative, humble and hopeful future.

Such are the blessings we are given when we learn to see the living earth and our rooted elder kin as the ancients did, as wise teachers, protectors, healers, sources of inspiration, regeneration and renewal.

When we learn to perceive and interact with our rooted kin (such as the Oak tree) as our ancestors did we shatter the modern illusion of separation that nation states attempt to impose on us and begin to speak a universal language that connects us all as equals.

While these days acorn recipes are mostly associated with Native Americans, they were a part of the traditional food supply in Greece, Italy, Spain, Albion, Eire, North Africa and throughout Asia. Oaks continue to produce abundant nutrition for humankind, even if we’ve largely forgotten how to harvest and prepare this free food source.

Acorn oil is still produced in the middle east, and an Arabian acorn-based drink was what eventually became modern hot cocoa. Acorn-based foods are produced commercially in Korea, for a savory tofu-like acorn gel and acorn udon noodles.

Oaks are home to more species of Nature’s creatures than any other tree. They foster a spectrum of mosses, lichens, insects, fungi, birds and critters within their sturdy branches. Woodpeckers, owls, bats, deer, squirrels, mice, wrens and jays all find food and shelter from this giving tree. The Oak willingly gives water and nutrients as a home for mistletoe. Just as well, Oak’s relationship with various funguses and ectomycorrhizae plays an important role in the establishment of healthy and fertile soil, and Oak forests are an ideal place to look for delectable truffles. Holes and crevices in the tree’s bark become nesting spots for beetles and large varieties of bugs. Over 5000 species of insects find their homes within Oak ecosystems.

The Oak tree is truly an entire kingdom unto itself.

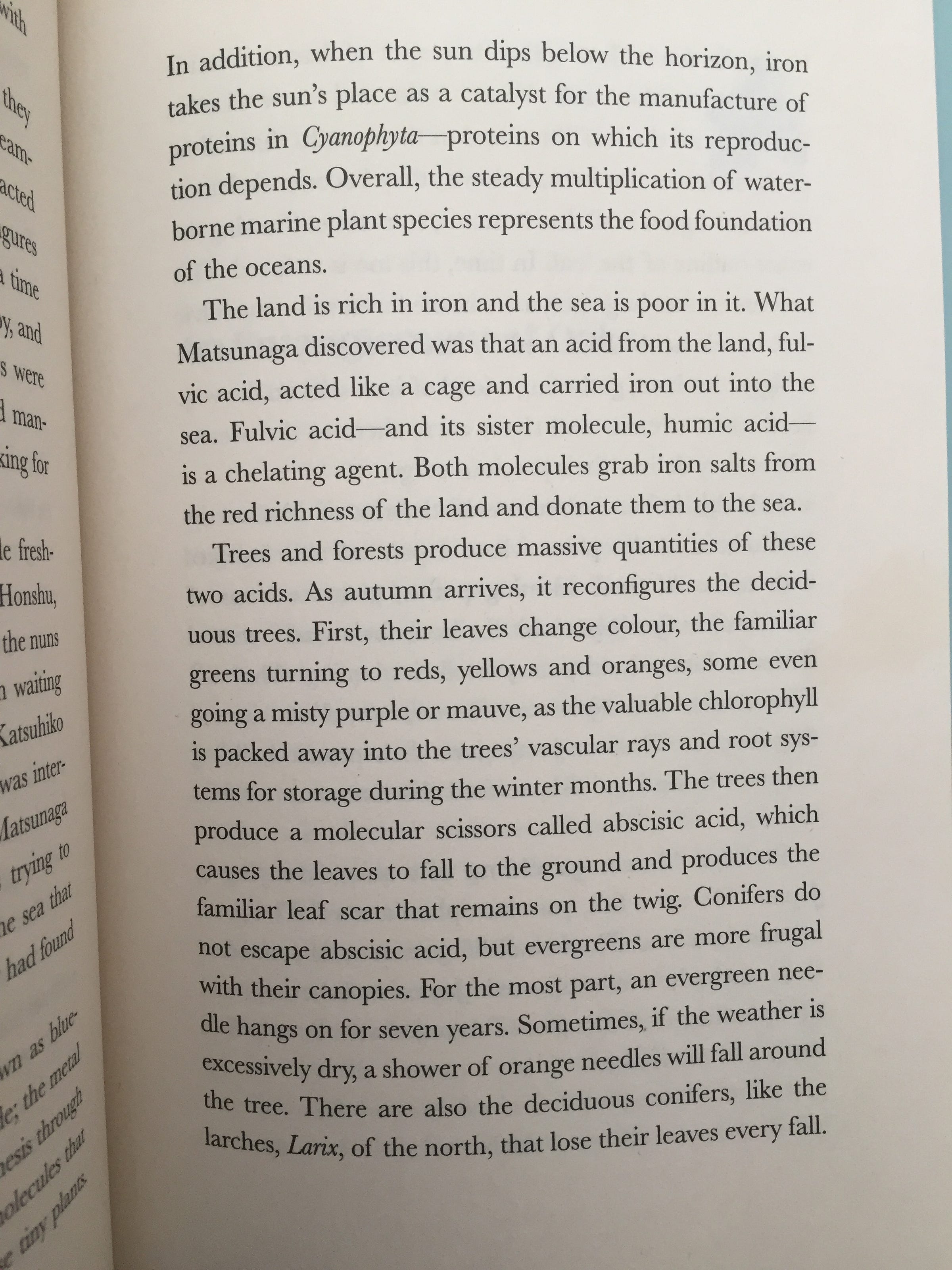

And the expansive generosity and magnanimous gifts of these long lived tall rooted beings does not stop at the forest’s edge, no, these beings seed the streams, rivers and ocean estuaries with the iron that supports the ecosystems of the sea. As I highlighted in my article on Regenerative Oceanic Gardening, deciduous Mother Trees such as the mighty oak literally seed the foundation of life forms that become the food for salmon, dolphins and whales and countless other ocean beings through the gifts of their decomposing leaves exuded into the waters.

That is one of the main reasons why as degenerate humans have deforested the once mighty oak forests of the Eastern Woodlands of Turtle Island, Éire, Albion and many other regions we are seeing a massive decline in the salmon runs in our rivers.

Considering the powerful influence of long lived deciduous Mother Trees (such as Oak and Hickory) in supporting the very foundation of ocean biology, perhaps it would be apt to expand Ralph Waldo Emerson’s wise words which I shared above to state:

“The creation of a thousand forests and ten thousand salmon is in one acorn”

Oaks feed animals on the land and in the ocean, they create and attract the rain, build the live giving soils and inspire our imaginations and art with their majesty. It is no wonder why ancient druids planted sacred oak groves and met in these groves to perform their ceremonies.

“The term “druid” is commonly translated “oak knowledge”, “oak-knower” or “oak-seer” referring to the fact that druids had knowledge of the oaks (and as oaks are a pinnacle species, therefore, druids had knowledge of the broader landscape) or perhaps, understood oaks on the inner and outer planes. In the druid tradition, oak is tied to that same ancient symbol of the druid possessing strength, knowledge, and wisdom. By taking on the term druid, we bring the power and strength of the oak into our lives and tradition.” -Dana O'Driscoll

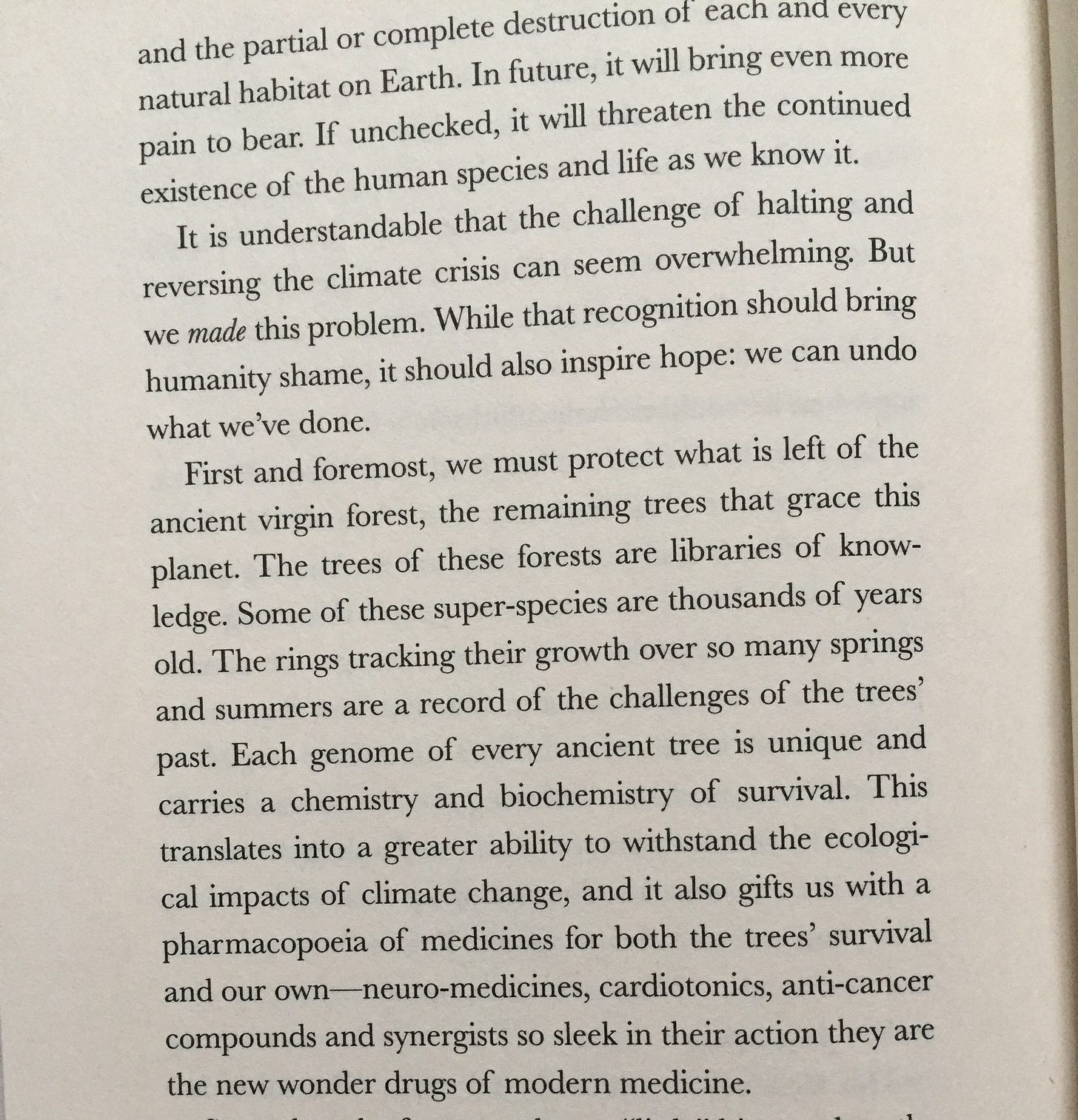

As is documented in "The Spirit of Trees: Science, Symbiosis and Inspiration", The Romans cut all of their sacred oak groves down. You can imagine what those ancient groves must have been like when you encounter even a single ancient oak tree–majesty and presence.

Oaks are an important botanical resource used in ceremony, food, medicine and building for as long as humans have been around.

It is in the gathering and eating of acorns that one becomes entwined with the web of life’s basic skills: foraging, Earth-centered interaction, ancestral rememberance, wildlife observation, forest conservation, human health, nutrition, and ecology.

Oak trees from which acorns come, teach us to be in right relationship with the natural world, rising our awareness to something greater than ourselves.

Oaks live all over the world, from Asia to North Africa to Europe to North America. And where there are acorns, people have eaten them. They have their own methods, too.

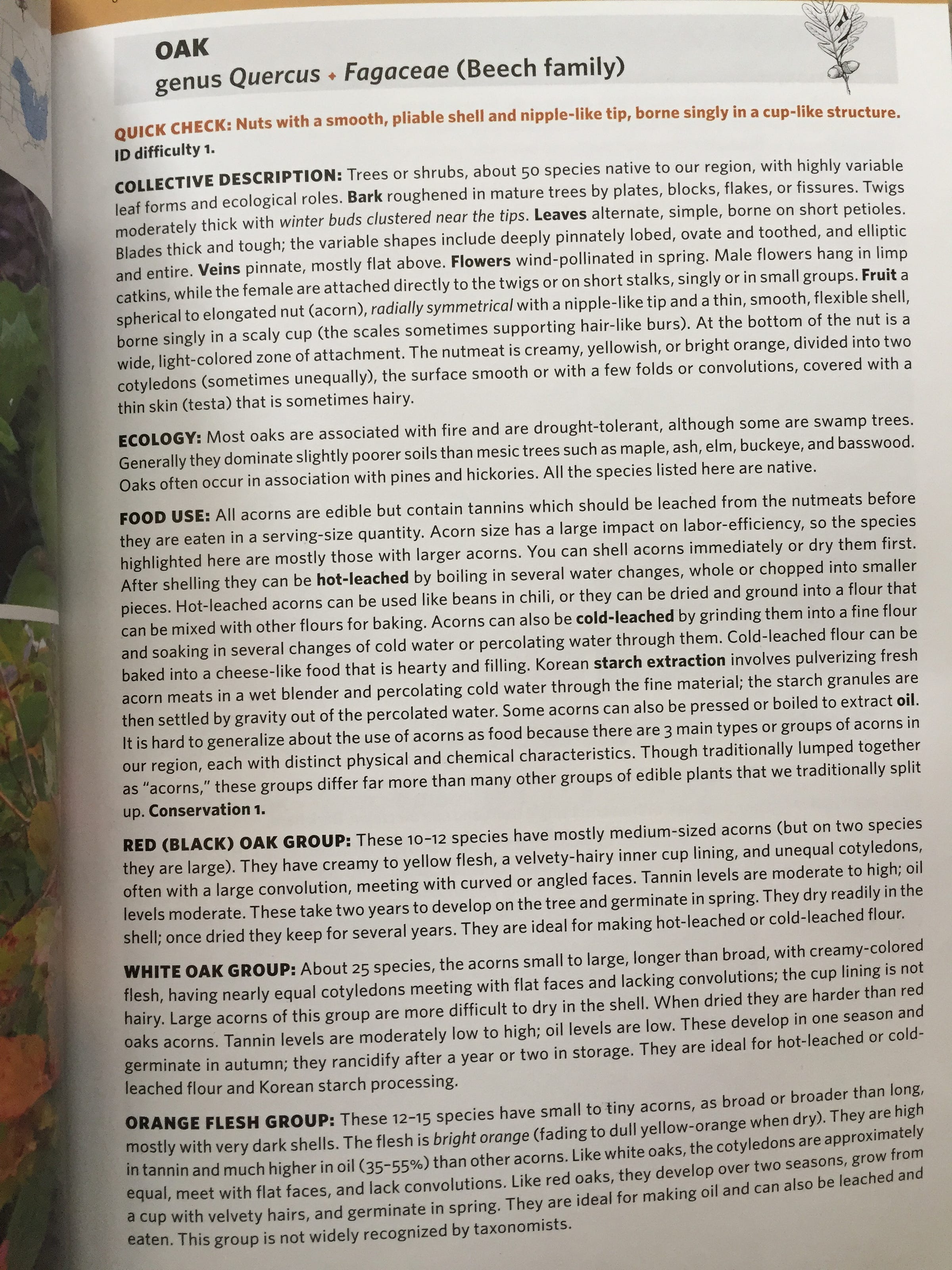

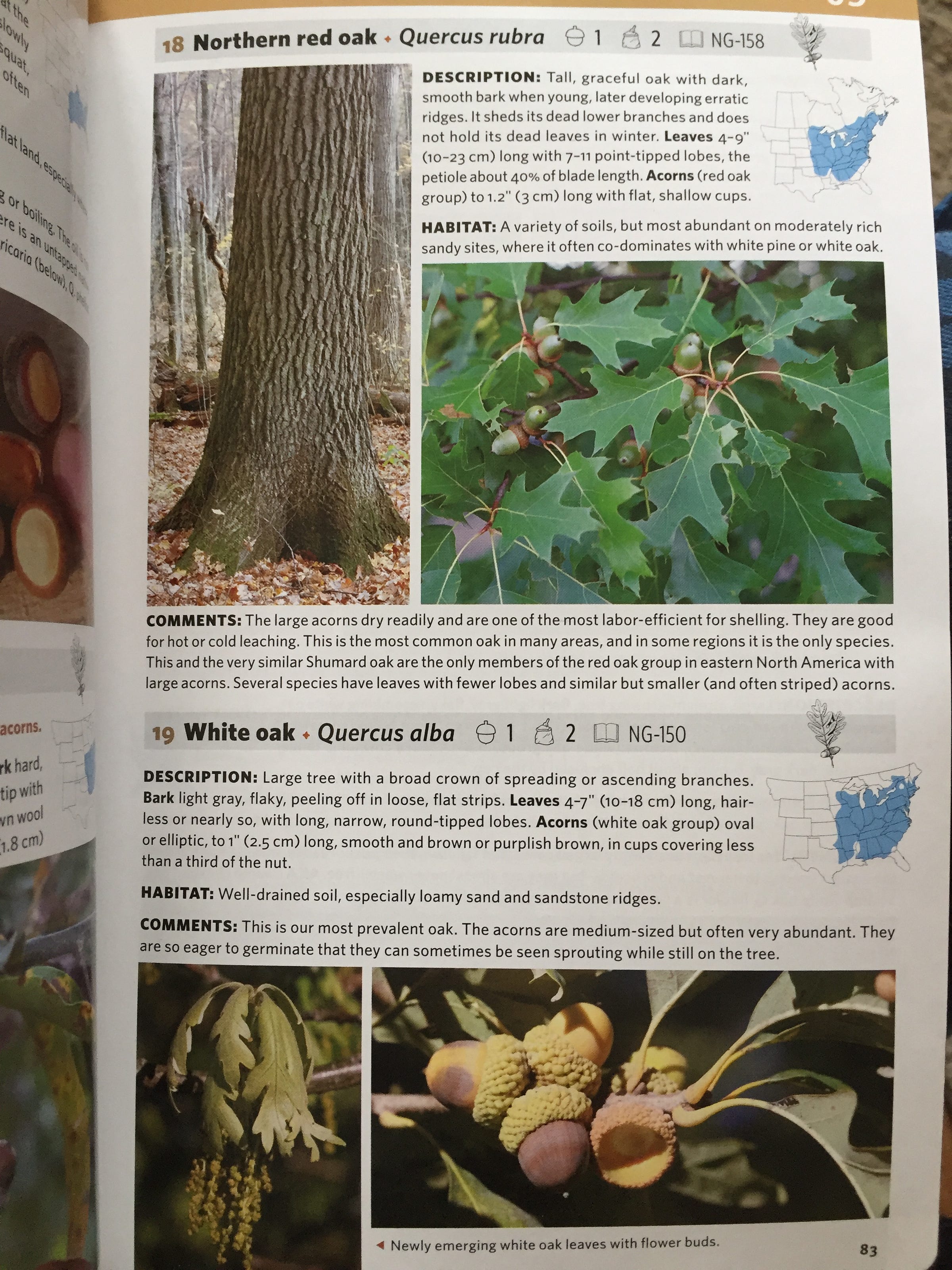

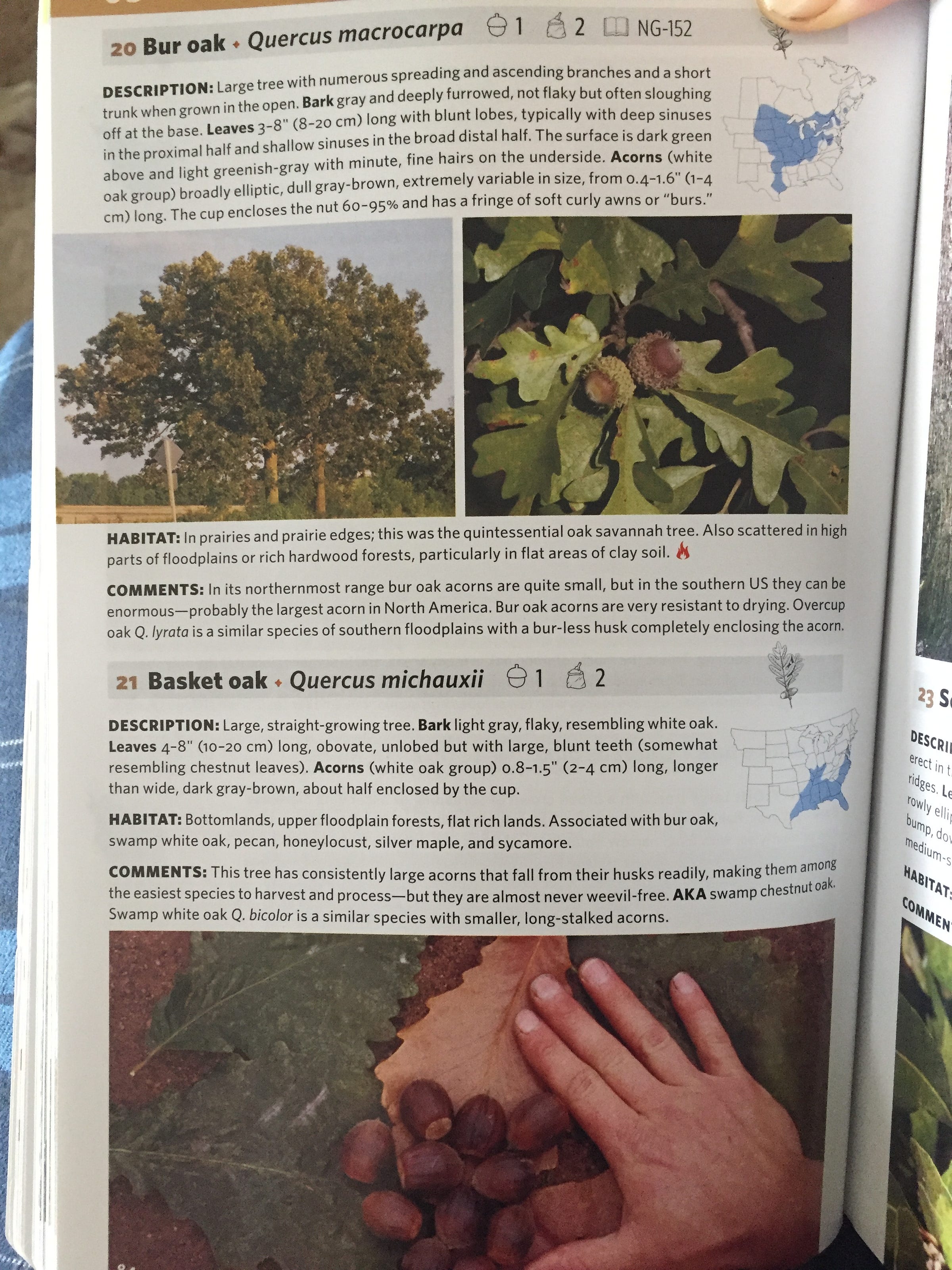

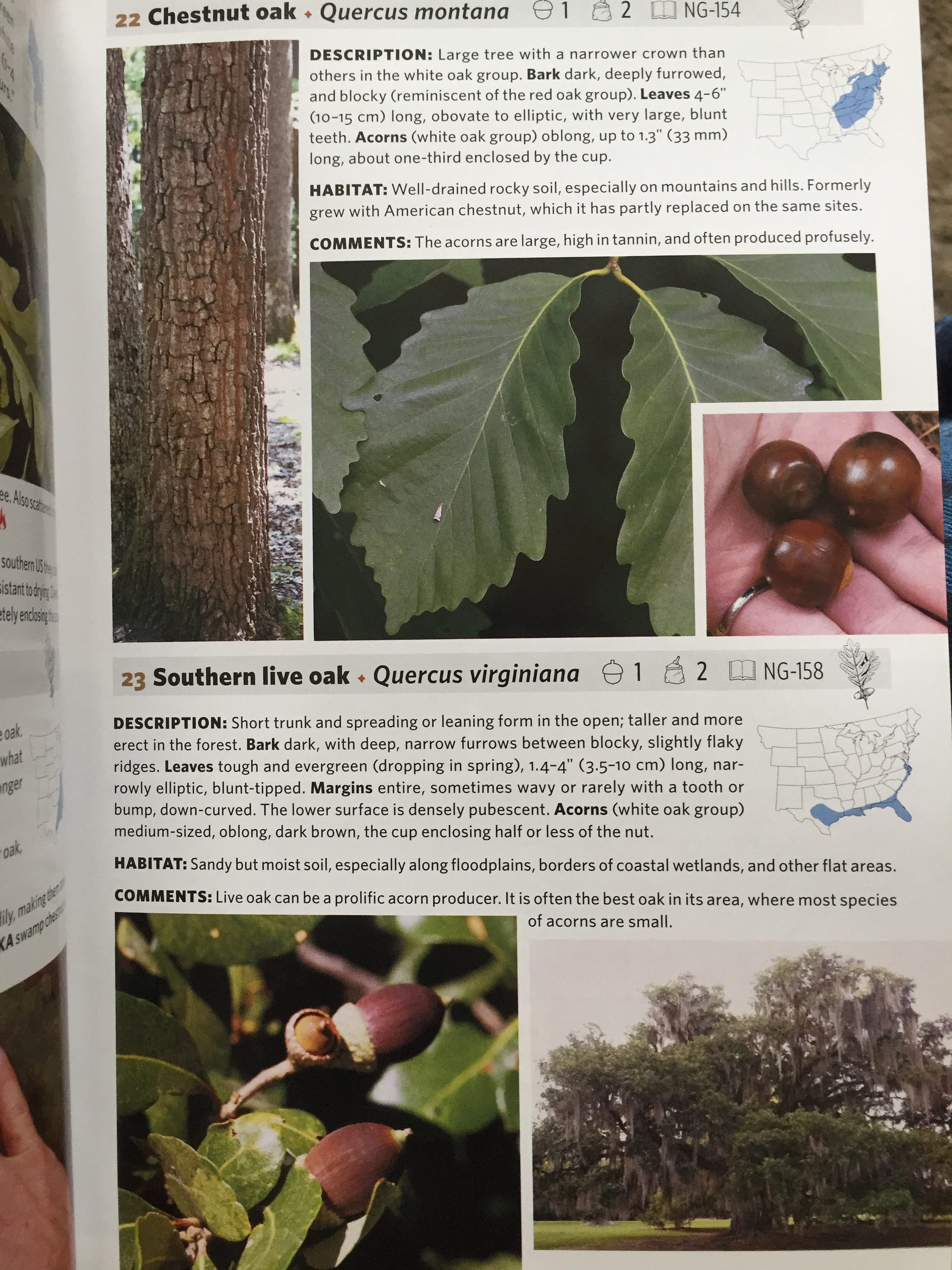

It is a good thing that there many species of Oak, however, covering them all comprehensively would require writing an entire book (or perhaps several volumes). Thus, I will be focusing on four main species (listed in large bold letters below). These are the species I am most familiar with here in the Eastern Woodlands of Turtle Island.

That said, you should know that if you were hoping for a quick summary about Oak trees that can fit into a twitter or facebook character count limit, this article is not that. As is the case with the longevity and story of Oaks on the planet Earth, this article vast and filled with nuance, depth and recalcitrance.

FYI: I will be sharing pictures from a number of books that offer empowering, educational and culturally enriching info in the post below. I hope that if any of you reading this find value in the pages shared, you will buy a copy of the book from the author (links are provided for you to do so) so you can support their ongoing works. I share this content as I know that not everyone can afford to buy books and I want people all over the world to be able to develop ecological literacy, ancestral awareness, food sovereignty, health food sovereignty and have hope for the future so I share this info for free here. Also, some of the material in the pictures of pages from books I share in the following article (especially in the history and cultural section) may have some overlap. I wanted to provide different author’s perspectives on the ethnobotanical and traditional folklore related to this tree so that people can cross reference and make up their own minds, but these people writing about oaks will inevitably share some of the same info as well. If you are able to reciprocate though supporting any of the authors of the books I share pics from below, I know they would be grateful.

Burr oak (Quercus macrocarpa) - Swamp White Oak (Quercus bicolor) - Northern Red Oak (Quercus rubra) - Black Oak (Quercus velutina) - Chinkapin Oak (Quercus muehlenbergii)

Common Names:

The Latin name “Quercus” is derived from a Gaelic word meaning “fine tree”.

Its common english name derives from the Anglo-Saxon word, ac, but in Irish the word is ‘daur’, and in Welsh ‘dar’ or ‘derw’, probably cognate with the Greek, ‘drus’. Some scholars consider this the origin of the term ‘Druid’, since Druids have always been associated with sacred groves, and particularly oak forests. Dense forests of oak once covered most of Northern Europe in those days, so it is not surprising to find this tree help most sacred by people who ‘live in oak forests, used oak timber for building, oak sticks for fuel, and oak acorns for food and fodder.’ Combined with the Indo-European root ‘wid’: to know, ‘Druid’ may have referred to those with ‘knowledge of the oak’, the ‘Wise Ones of the Oakwood’. The Sanskrit word, ‘Duir’, gave rise both to the word for oak and the English word ‘door’, which suggests that this tree stands as an opening into greater wisdom, perhaps an entryway into the otherworld itself.

The Burr Oak has many common names, including: Mossycup oak (A common name for the bur oak, due to the fringed acorn cups), “Blue Oak” and “Scrub Oak”.

Swamp White Oak is also sometimes called The Bicolor Oak. Also known as mitig'omish in the Potawatomi language.

Northern Red Oak is so named to distinguish it from southern red oak (Q. falcata) though it is often just referred to as the Red Oak locally. Also known as the Spanish Oak and sometimes called the Champion Oak.

Black Oak is also known as Eastern Black Oak, Quercitron Oak, Smoothbark Oak and Yellowbark Oak.

Chinkapin Oak also known as yellow chestnut oak, rock oak or yellow oak.

Family: Fagaceae

Part used for medicine/food: Bark, Leaves, Acorns, Roots and Galls

Constituents:

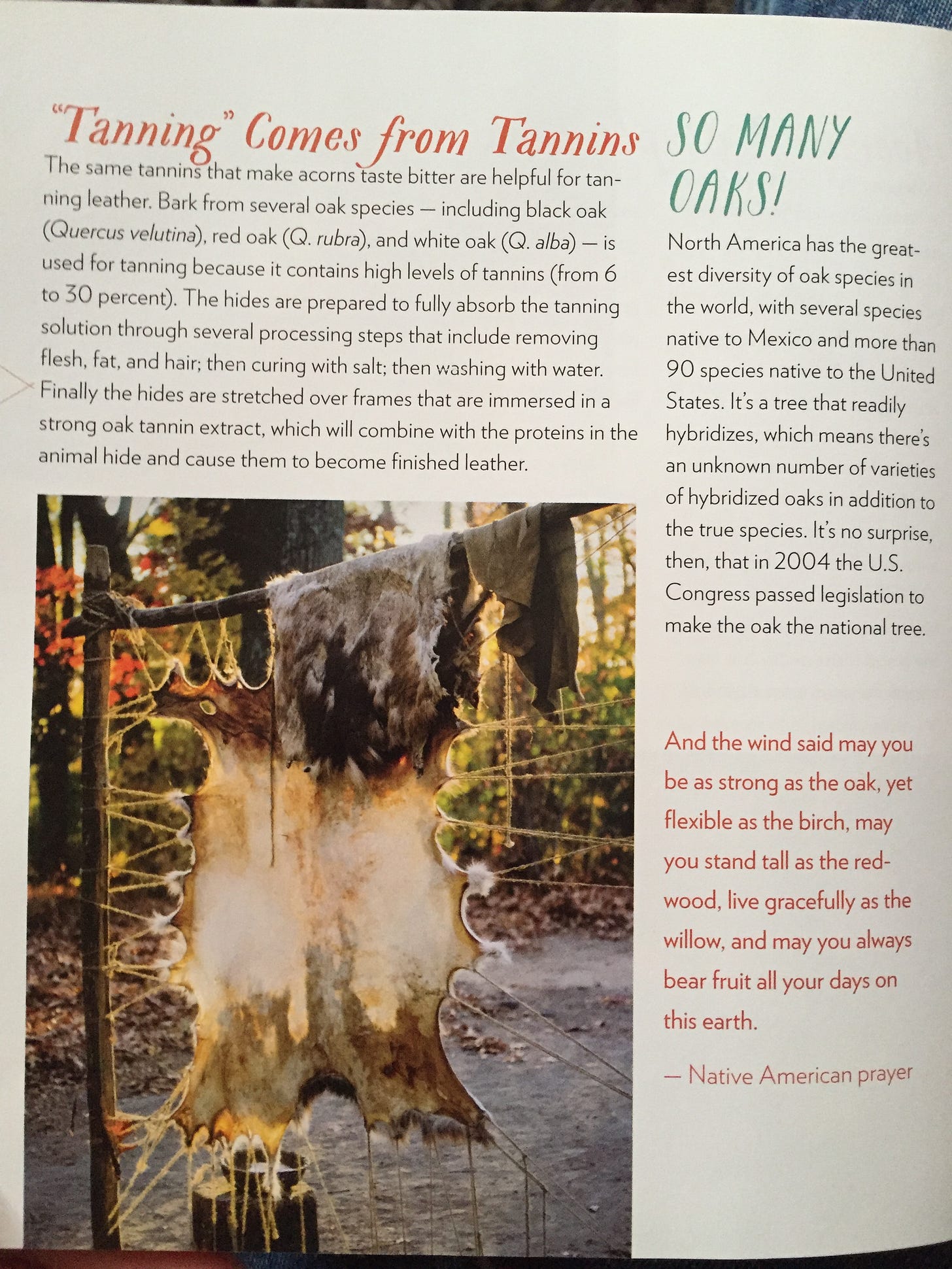

Tannins (up to 15-20% consisting of phlobatannin, ellagitannins, and gallic acid) glycosides, terpenoids, flavonoids, phenolic acids, fatty acids, sterols, picraquassioside D, quercussioside, lyoniresinol-90α-O-β-D-xylopyranoside, (catechin, (epicatechin, procyanidin B3, procyanidin B4, quercuschin, methyl gallate, betulinic acid, β-sitosterol glucoside, eupatorin (5,3′-dihydroxy-6,7,4′ trimethoxyflavone), cirsimaritin (4′,5, -dihydroxy-6,7-dimethoxyflavone), betulin (lup-20(29)-ene-3, 28-diol), and β-amyrin acetate (12-oleanen-3yl acetate).

Acorns are especially high in carbohydrates, healthy fats, protein, potassium, iron, vitamins A and E, Manganese, Vitamin B6, Folate, catechins, resveratrol, quercetin, and gallic acid — potent antioxidants that help protect your cells from damage and several other important minerals.

Medicinal actions:

Anti-tumor, antibiotic, anti-parasitic, Astringent, hemostatic, antiseptic, anti-inflammatory, antibacterial, hepatoprotective, antidiabetic, anticancer, gastroprotective and antioxidant.

Also used to treat colitis, stomatitis, labor pains, obesity related diseases, astrictiona, diarrheaa, furuncles, treatment of tonsillitis, and throat infections, chronic skin diseases such as eczema and varicose veins.

Teas used for for female disorders, ointment for wounds, diaphoretic, hemorrhoids and intestinal inflammation.

Powder of gallnuts of one species of oak is used to restore the elasticity of the uterine wall, as well as to treat aphthous ulcers [31, 39].

Pharmacology:

Oak (Quercus) has many pharmacological properties, including antioxidant, anti-inflammatory, and antimicrobial properties. These properties are due to the presence of chemical compounds such as tannins, flavonoids, and triterpenoids.

Pharmacological properties

Antioxidant: Oak has strong antioxidant properties that may help treat diseases associated with oxidation, such as diabetes, cancer, and cardiovascular disease

Anti-inflammatory: Oak has anti-inflammatory properties that may help treat skin disorders and inflammatory diseases

Antimicrobial: Oak has antimicrobial properties that may help treat infections

Hepatoprotective: Oak has hepatoprotective properties that may help protect the liver

Gastrointestinal: Oak has gastrointestinal properties that may help treat diarrhea, gastric ulcers, and hemorrhoids

Wound healing: Oak has wound healing properties that may help treat wounds

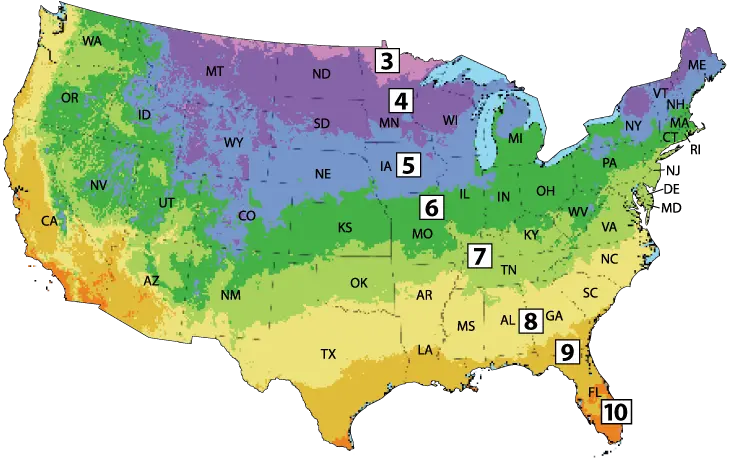

Cold Hardiness:

Burr oak (Quercus macrocarpa): 3a – 9b

Swamp White Oak (Quercus bicolor): 3 - 8

Northern Red Oak (Quercus rubra): 3 - 8

Black Oak (Quercus velutina): 3 - 9

Chinquapin Oak (Quercus muehlenbergii): 3 - 9

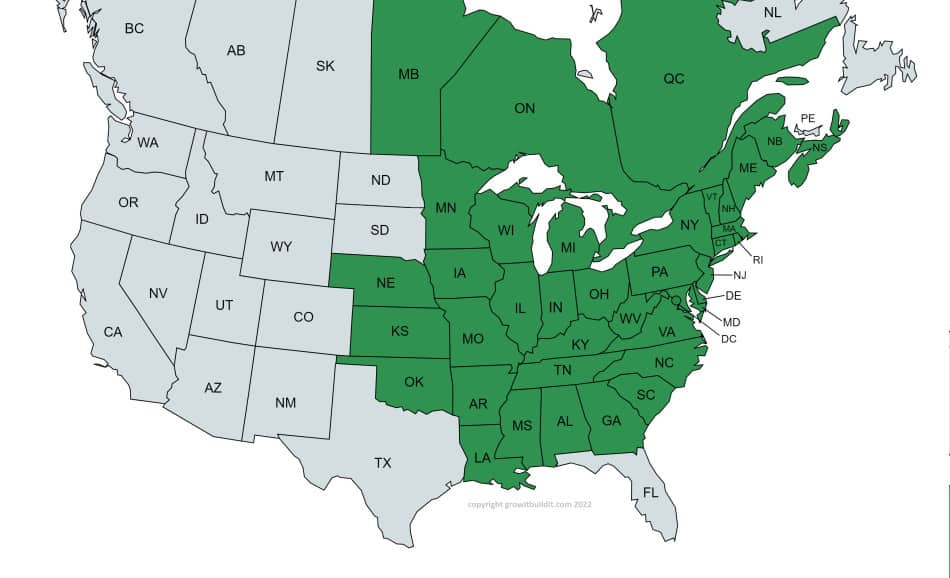

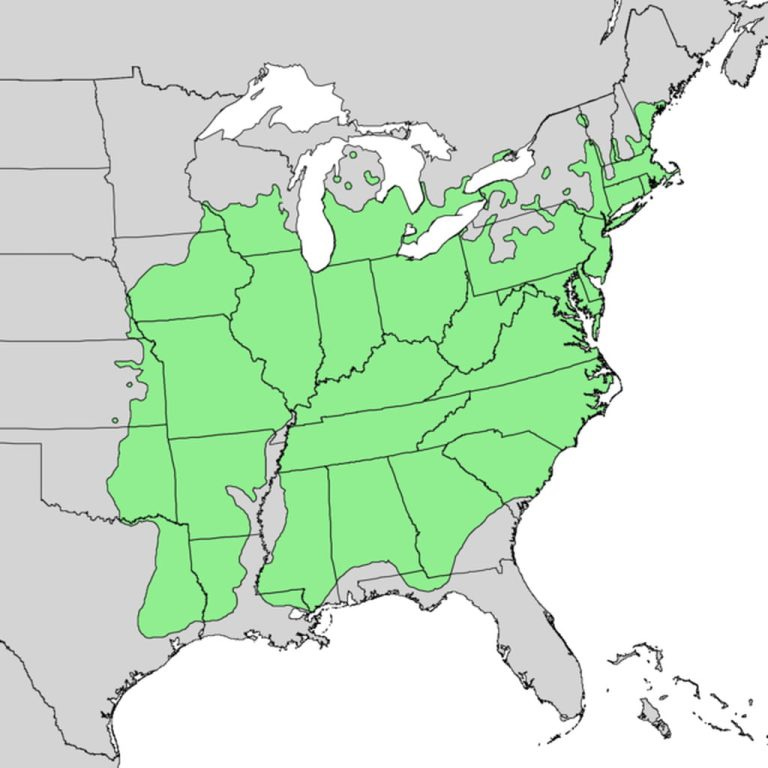

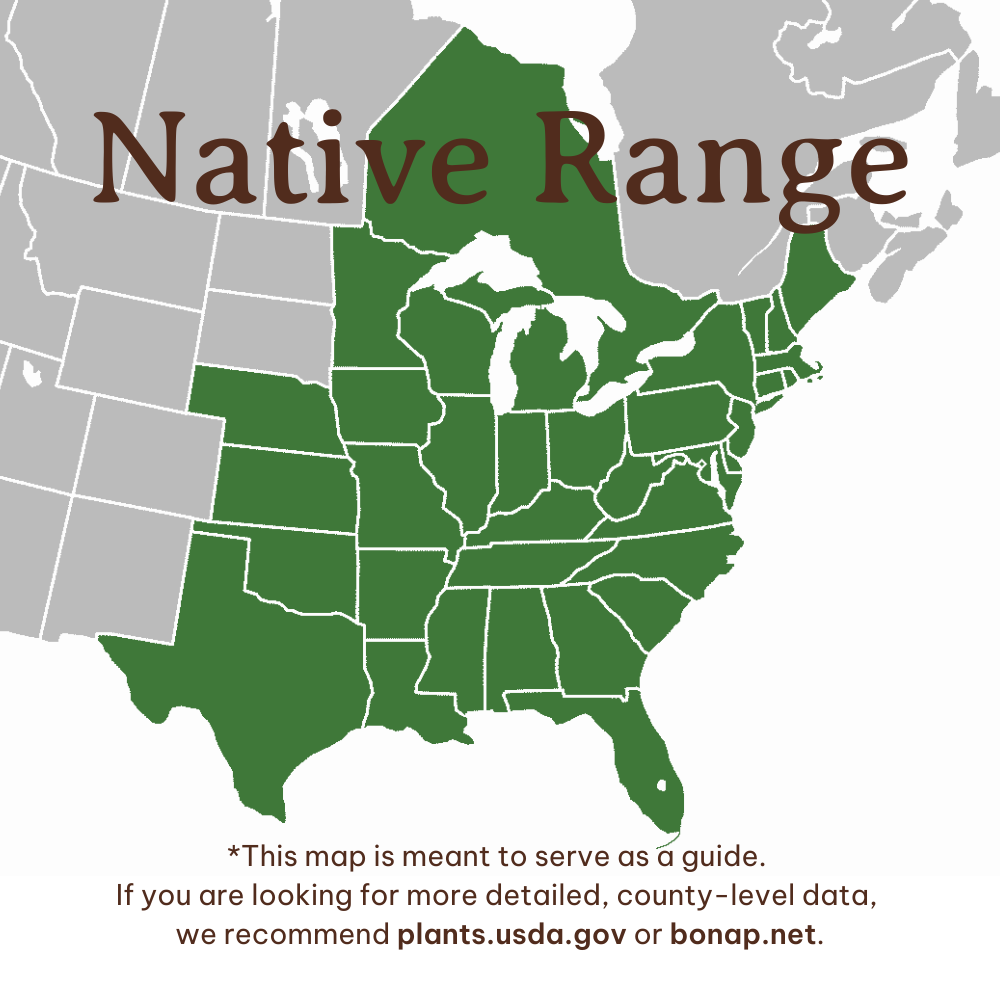

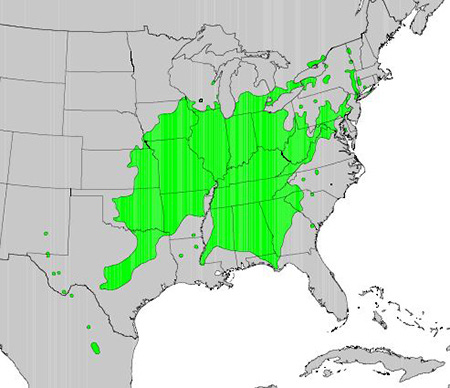

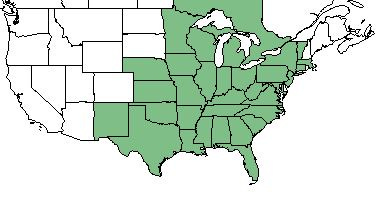

Native Range:

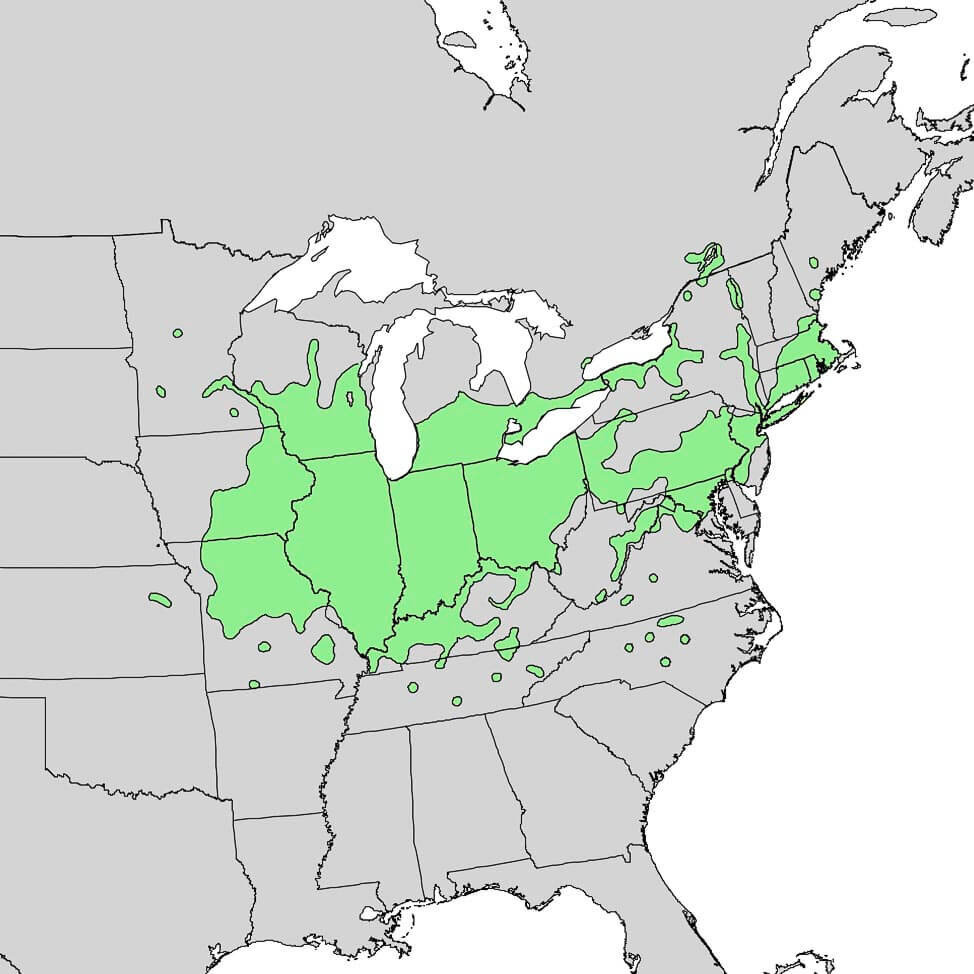

Burr oak (Quercus macrocarpa):

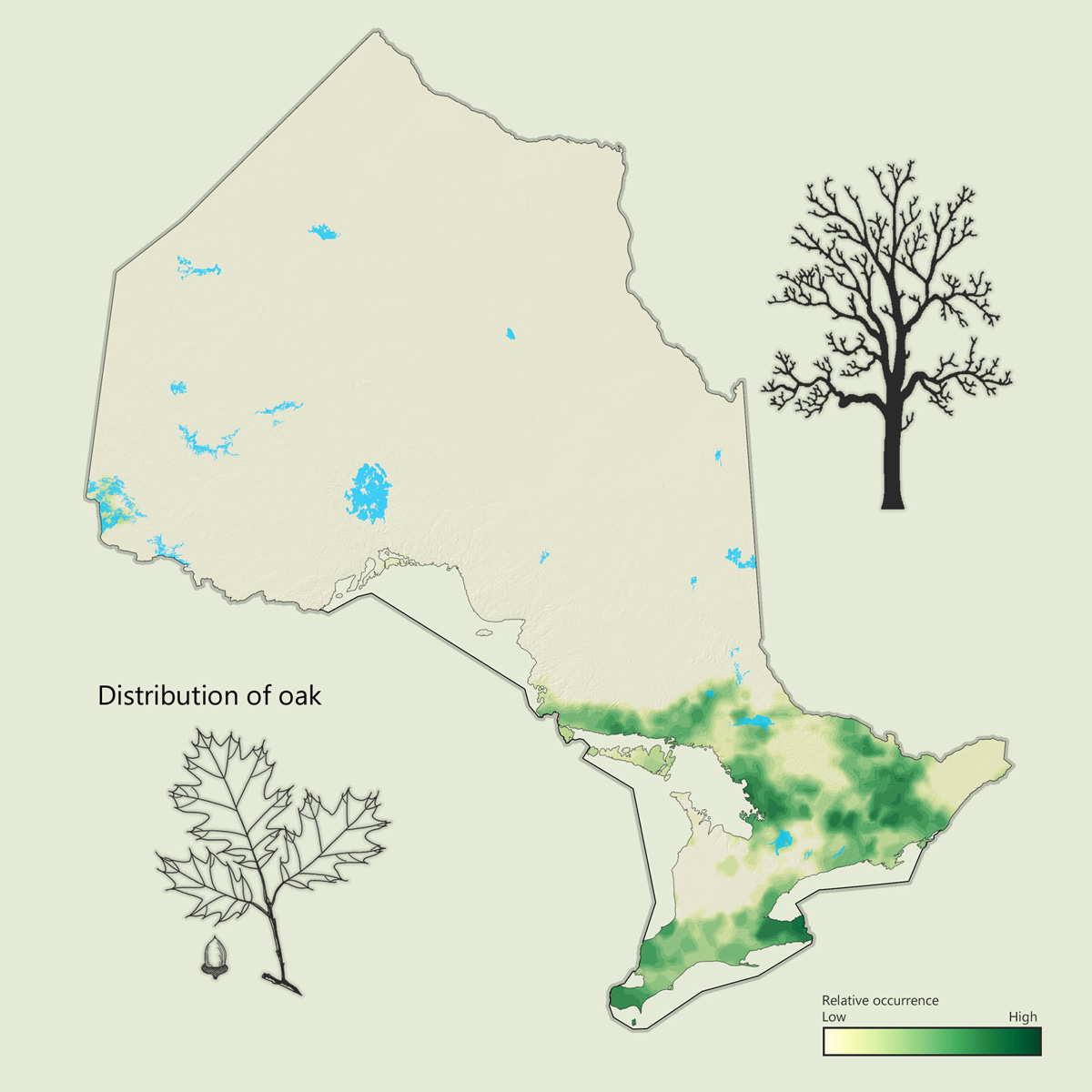

Native to eastern North America, from Nova Scotia to Texas, and from New Brunswick to Manitoba. It also grows in parts of Canada, including Ontario, Quebec, and Saskatchewan.

Range

Eastern United States: From New Brunswick to North Carolina, and from Alabama to Pennsylvania

Great Plains: From North Dakota to Texas, and from Montana to Nebraska

Canada: From Nova Scotia to Manitoba, and from Ontario to Saskatchewan

Habitat

Open spaces

Bur oaks grow in open areas, away from dense forests. They are often found near waterways, in oak savannas, and on sandy ridges.

Soil

Bur oaks grow well in a variety of soils, including limestone, clay, and rocky hillsides. They prefer full sun conditions.

Climate

Bur oaks grow in temperate climates. They are drought-tolerant and can withstand harsh conditions.

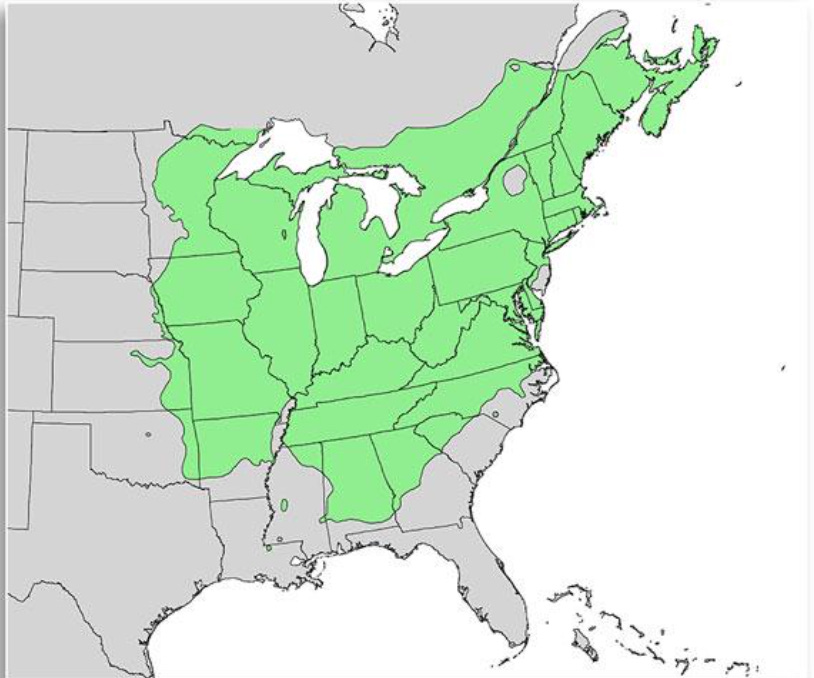

Swamp White Oak (Quercus bicolor):

Swamp White Oak are native to North America and can be found in the northeastern and north central United States. Its native range includes parts of Maine, New York, Quebec, Ontario, Michigan, Wisconsin, Minnesota, Iowa, Missouri, Kentucky, Tennessee, Virginia, and New Jersey.

Habitat:

Swamp white oaks grow in bottomland areas. They can survive in a variety of habitats. They grow best in moist, well-drained soils. They can grow in areas that are flooded in spring but dry in summer.

Northern Red Oak (Quercus rubra):

Northern Red Oak is native to eastern and central North America, from Nova Scotia to Georgia. It also grows in southeast and south-central Canada.

United States

Minnesota to eastern Nebraska and Oklahoma

East to Arkansas, southern Alabama, Georgia, and North Carolina

Outliers in Louisiana and Mississippi

Canada

Nova Scotia to northeastern Ontario

Throughout the southern half of the Algoma District

Habitat

Mesic upland forests

Ravines

North and east slopes

Sunny, moist to well-drained or dry upland slopes and ridges

Deciduous and mixedwood forests

Black Oak (Quercus velutina):

Chinkapin Oak (Quercus muehlenbergii)

Chinkapin Oak is native to eastern and central North America, including parts of the United States and Canada.

United States

New England and Pennsylvania

Virginia and the Carolinas

Northwestern Florida

Northern Mexico

South-central Texas

Oklahoma

Minnesota

Wisconsin

Southern Ontario

Southern Michigan

Canada

Southwestern and Southeastern Ontario near the Great Lakes and St. Lawrence River

Mexico Coahuila south to Hidalgo.

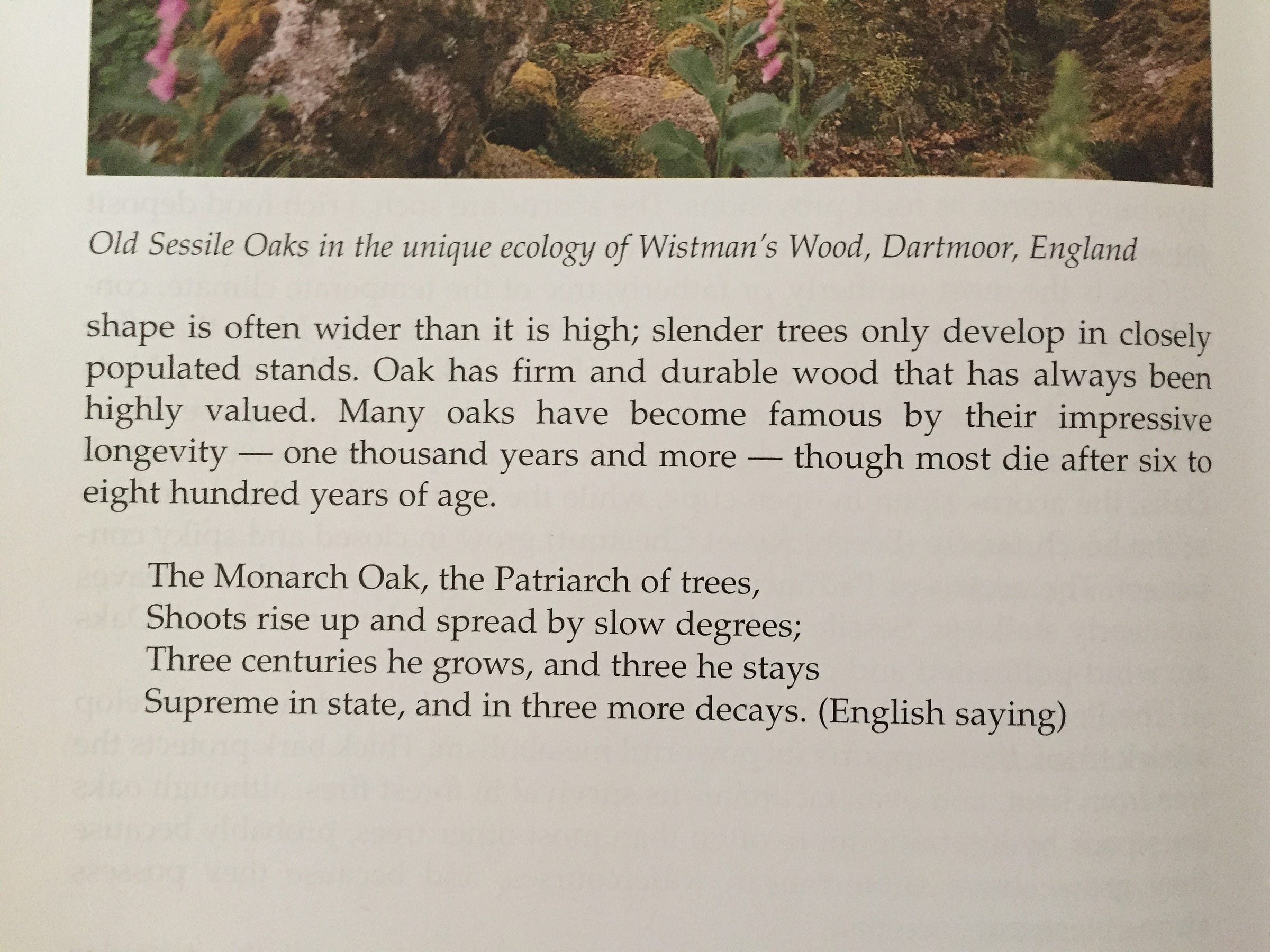

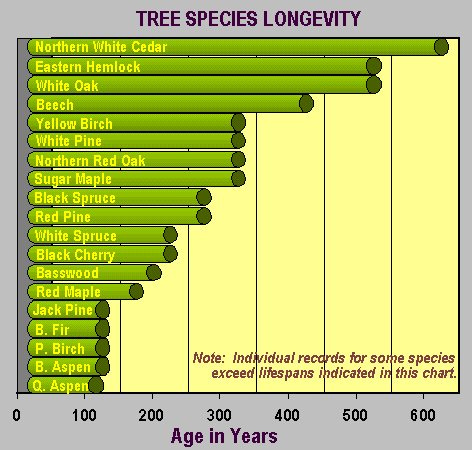

Growth Form/longevity:

Burr oak (Quercus macrocarpa):

a medium to large deciduous tree with a broad, rounded crown. It's one of the largest native oaks in North America.

Lives to be 300-528 years old in ideal growing conditions (and with a lack of degenerate humans nearby).

Size

Typically grows to be 60–90 ft (18–24 m) tall, but can reach 160 ft (46 m) in ideal conditions (and with a lack of degenerate humans around).

Trunk can be 60–120 cm (24–48 in) in diameter

Canopy can be wider than it is tall in the open

looking up the trunk of a 300 year old plus Burr Oak, southern Ontario, 2025. This tree is over 100 feet tall and has no horizontal branches until about 60 feet up the trunk due to his proximity to neighboring Red Oak and Shellbark Hickory trees.

Shape

Broad-spreading, rounded crown

Symmetrical canopy with a regular outline

Heavy, horizontal limbs

Deep-ridged bark

Leaves

Up to 9 in long

Central midrib with branch veins leading into rounded lobes

Lobes separated by deep sinuses

Wavy margined lobes longer and broader than those toward the base

Swamp White Oak (Quercus bicolor):

medium-sized, deciduous tree with a broad, rounded crown and a short trunk when growing in the open.

Can live from 300 - 550 years in ideal growing conditions (and with a lack of degenerate humans nearby).

Size:

Typically 50–60 ft tall and wide

Can grow to be 70-95 ft tall (in ideal growing situations and with a lack of degenerate humans present)

Shape:

Upright, oval-shaped crown

Broad, open canopy

Young trees are pyramidal in shape

Leaves:

Shiny, dark green above

Silvery white beneath

5–10 rounded lobes or blunt teeth along the margins

3–7 in long and 1.25–4 in wide

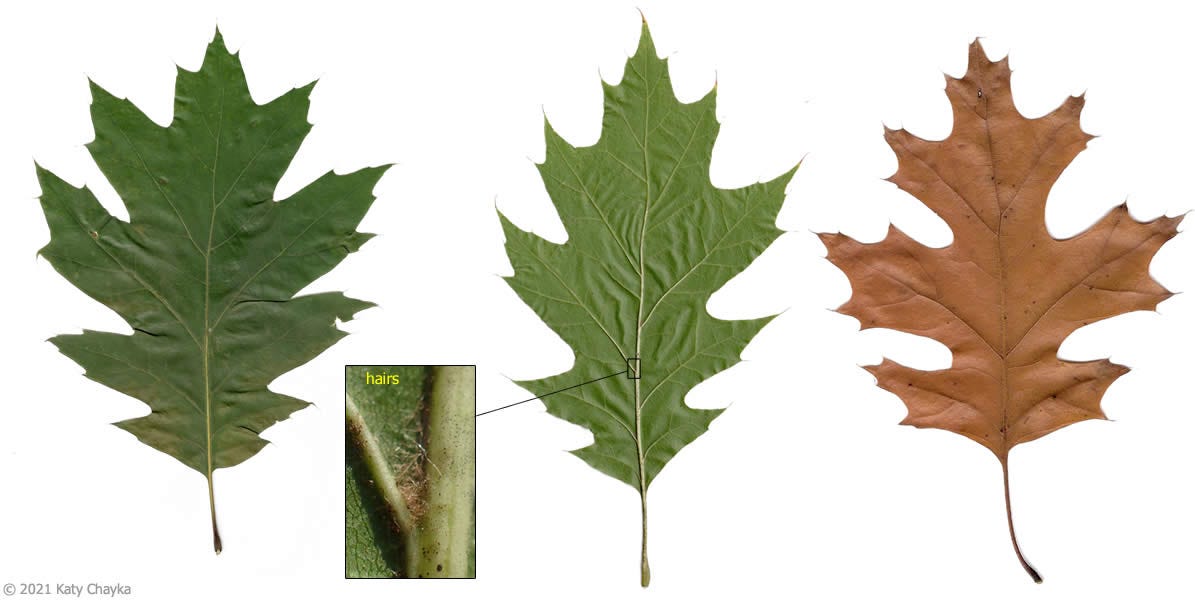

Northern Red Oak (Quercus rubra):

has a rounded to broad-spreading crown and can grow to be a large deciduous tree.

Can live from 350-500 years in ideal conditions (and with a lack of degenerate humans nearby).

Height and spread

Can grow to be 50–75 ft tall

Can spread to be 40–60 ft wide when open-grown

Can grow to be 90-140 ft tall in rich woodland areas (with a lack of degenerate humans nearby)

Leaves

Broad, dark green leaves with 7–11 toothed lobes

Leaves turn russet-red to bright red in the fall

New leaves are light red in the spring

Black Oak (Quercus velutina):

This tree has an upright, rounded growth form with a broad, spreading crown.

Can live 250-330 years in ideal conditions and with a lack of degenerate humans nearby.

Height and spread

Black oaks can grow to be 50–80 ft tall

They can have a spread of 50–60 ft

They can have a trunk up to 90 cm in diameter

Branches

Black oaks have large, spreading branches

Their branches form an open crown that is often irregular

Leaves

Black oak leaves are thick, glossy, and pointed-lobed

They are often dark green above and yellowish below

They can turn orange or red in the fall

Bark

Black oak bark is dark gray and smooth when young

It becomes almost black and ridged with age

The inner bark is yellow or orange

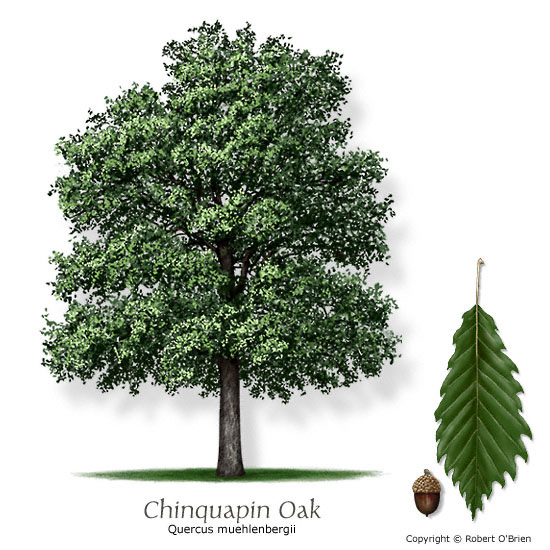

Chinkapin Oak (Quercus muehlenbergii)

Chinkapin Oak (Quercus muehlenbergii) are deciduous, oblong, and have a shiny green upper surface and a pale underside. The leaves are coarsely toothed and have a small gland or callus at the tip of each tooth.

These tall rooted beings can live over 500 years in ideal growing conditions (and with a lack of degenerate humans present).

Size and shape

Leaves can be 10–18 cm long and 2.5–10 cm wide

Leaves can be oblong, lanceolate, or obovate

Leaves have 8–14 teeth on each side

Leaves have a pointed tip and a rounded or acute base

Other characteristics

Leaves are leathery

Leaves have a dark, glossy yellow green upper surface

Leaves have a white underside with soft hairs

Leaves alternate on the tree

Growing conditions

Chinkapin oak is a native North American shade tree that grows in well-drained soil in full sun. It can grow to be 50–95 ft tall and 50–70 ft wide.

(Updated:

has expressed that she does not want her material shared here and that she supports the corrupt laws of immoral statist regimes, so her material has been removed)Reproduction:

Oaks are wind-pollinated trees with male and female flowers on the same tree

The age of first reproductive cycle (acorns produced) varies by location, tree density, and life span.

Reproductive cycles

White oaks: Require one growing season from pollination to acorn maturation

Red oaks: Require two growing seasons from pollination to acorn maturation

Habitat and Ecological Niche:

The Ecology of Oak Trees

In the 56 million years since they first appeared, oaks went from one species in one place to over 400 species that expanded to five continents.

Today, you find oaks growing around the globe in all sorts of soil types, elevations, temperatures, and rainfall levels.

With 400-plus species, there’s a good chance there’s an oak suited to most places on Earth.

Oaks are most plentiful across North America, Central America, Europe, and Asia.

New species are still being found in Central America, Southeast Asia, and—mostly—Mexico—where there are almost twice as many oak species as the United States and Canada combined.

In American forests, oaks are the dominant tree with more biomass than any other tree. Pines are a close second.

There are no oaks in Antarctica and any found in Australia and New Zealand were introduced, not native.

Oaks split into eight major lineages pretty early on. Here in North America we have two in particular that are notable: white oaks and red oaks which can be found growing together in the same regions.

White Oaks Versus Red Oaks

A quick way to tell them apart is the leaves. White oak leaves tend to have rounder lobes while red oak leaves have pointier or “bristle” tips. Each group also tends to be resistant to different pests and diseases.

“Oaks support more forms of life and more fascinating interactions than any other tree genus in North America.” — Douglas Tallamy, The Nature of Oaks

Oaks are a keystone species, which can be defined as a species that has a larger effect on its ecosystem that would be expected by its relative abundance. Keystone species play critical roles in maintaining the structure and stability of an ecosystem and affect the type and abundance of other species.

Throughout their native range, oak trees not only provide food, they also:

Offer shelter, from their roots to treetops, for an array of organisms.

Provide shade under their broad canopies that helps soils retain moisture and keep it cool.

Reduce erosion with their extensive root systems.

Sequester large amounts of carbon.

Oaks support an astonishing array of insects. Over 900 species of butterflies and moths rely on oaks — even though their flowers offer no nectar since they are wind-pollinated. Oak leaves are the primary diet or “host plant” for these animals as caterpillars.

Oaks as Food and Habitat

While acorns are an abundant food source, the whole oak tree—acorns, leaves, branches, trunk, and roots—is an important source of life for countless beings both as it lives and dies.

Acorn Eaters:

Over 100 vertebrate species in the United States eat acorns including:

Blue jays

Chipmunks

Crows

Deer

Flying Squirrels

Foxes

Mice

Opossums

Quail

Rabbits

Raccoons

Rats

Red-bellied woodpecker

Tufted titmouse

White-breasted nuthatch

Wild turkeys

Wood ducks

Quail

Rabbits

Raccoons

Rats

Red-bellied woodpecker

Tufted titmouse

White-breasted nuthatch

Wild turkeys

Wood ducks

Blue Jays & Oaks

Blue jays have formed a special relationship with oaks. The jay gets food and the oak tree gets help with acorn seed propagation.

Like squirrels, jays are “scatter hoarders.” Instead of a single food cache, they bury acorns throughout their territory. They can do this because jays have a flexible esophagus which allows them to transport one or two acorns at a time without damaging the seed.

In just one season, a single jay can stash thousands of acorns—far more acorns than it could ever consume.

Buried just below the soil surface, the acorns are placed at a depth that happens to be right for germination.

If conditions are favorable all the way along, those acorns will sprout and grow into new oak trees—sometimes as much as a mile from the mother tree.

Throughout all these stages, oaks support a diverse range of living things including birds, insects, mammals, fungi, and other microorganisms. And many of the insects and arthropods including caterpillars that feed off oaks are then themselves food for other wildlife.

If you live in a region with lots of oaks, you may have noticed some interesting characteristics.

Galls:

Have you seen bumps or other odd growths on oak leaves? These are galls created by tiny wasps, which are, in turn, parasitized by other insects, in a fascinating display of interconnection among species. The galls cause little to no damage to the oaks.

Leaf litter:

Fallen oak leaves decompose more slowly than those of most trees. This leaf litter provides a thick, protective blanket for soil-dwelling creatures.

Masting:

Many oak trees produce widely varying crops of acorns year to year. For example, an oak may produce a bumper crop one year (called masting) and produce fewer acorns over the next few years. Producing acorns requires much energy for a tree. Ecologists hypothesize that they produce an abundant crop one year to ensure that at least some of the acorns will be around to germinate and grow after squirrels and other hungry animals have had their fill. Over the next few years, the trees build up the energy they’ll need for the next bumper crop.

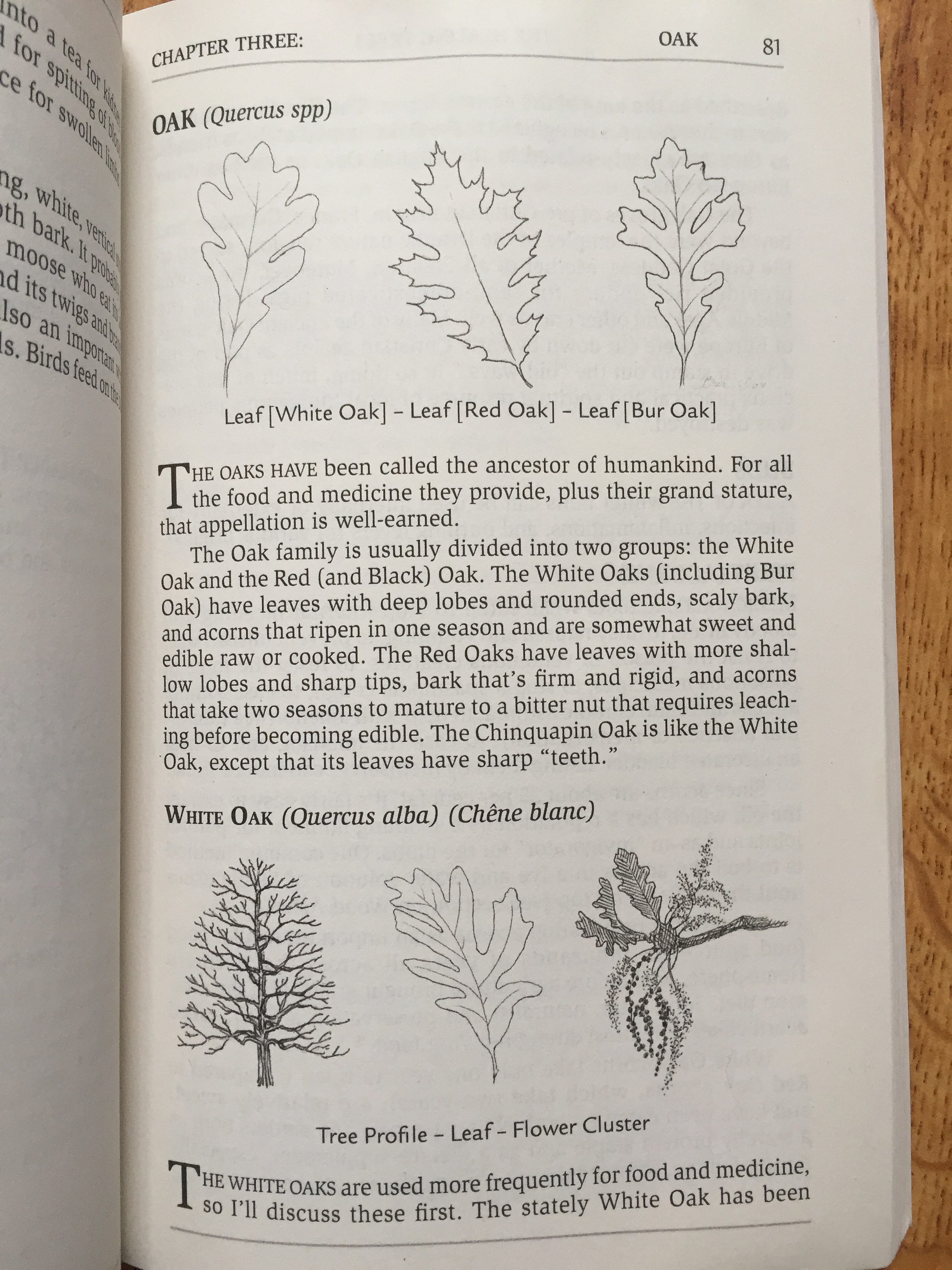

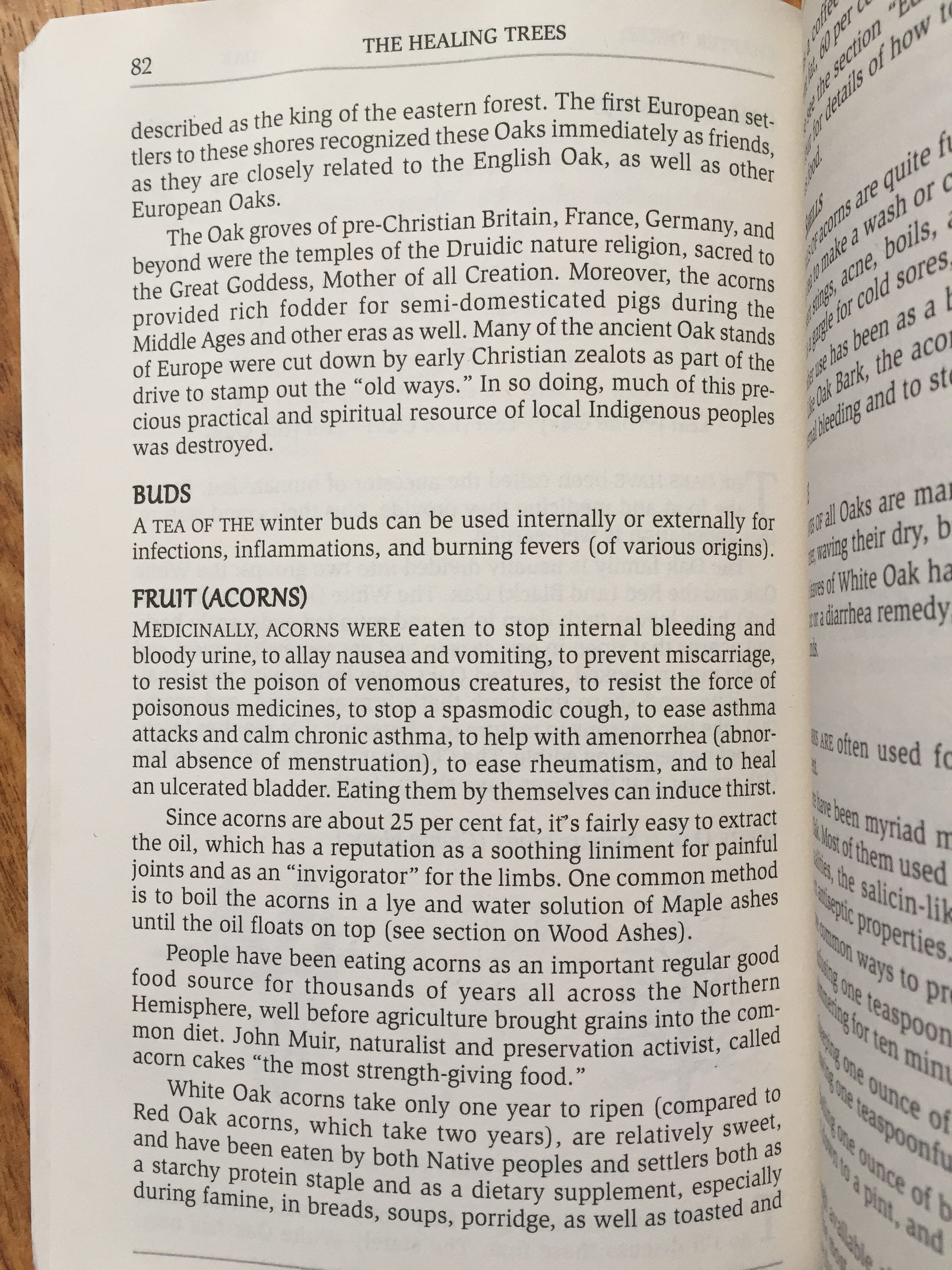

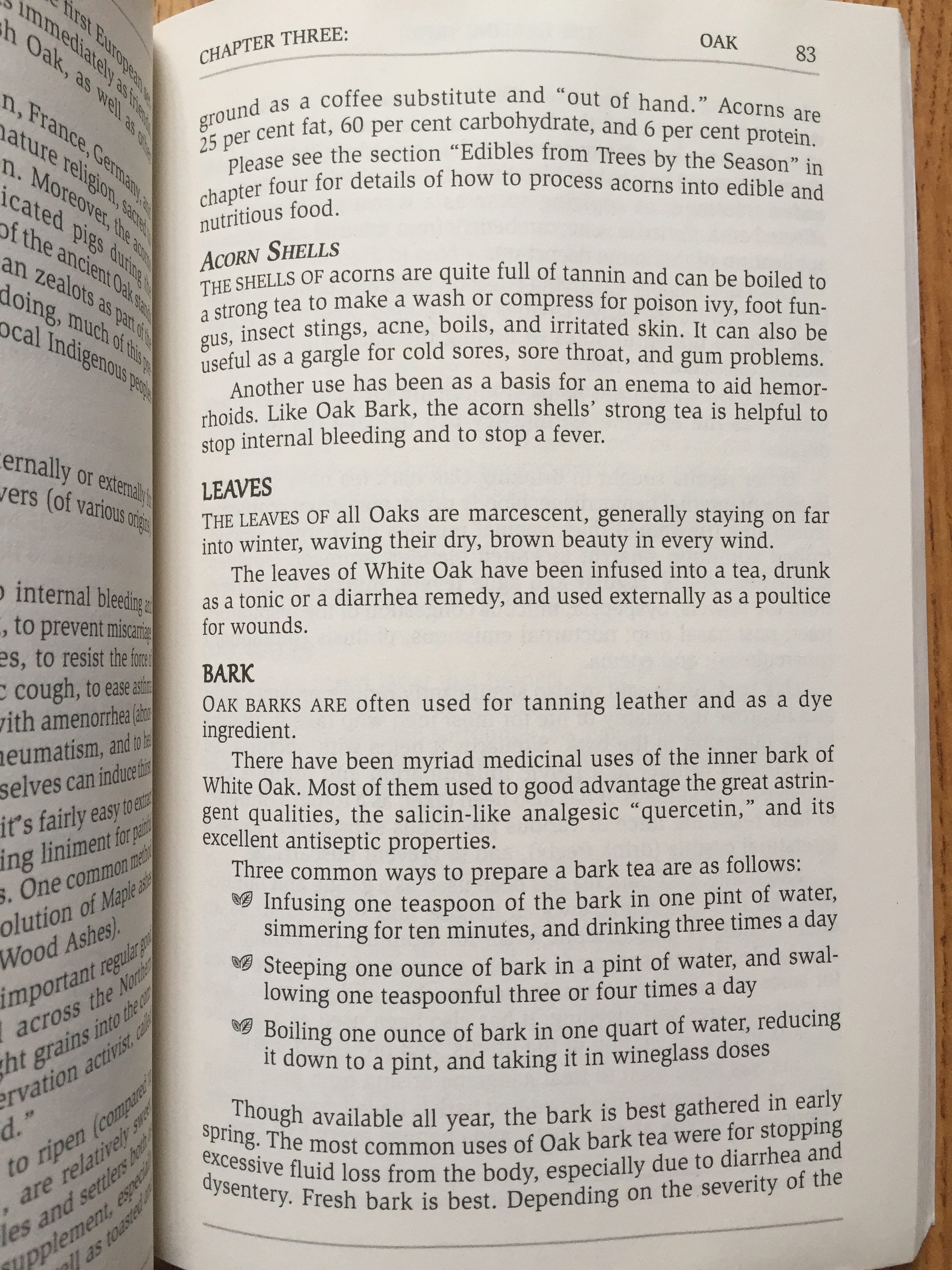

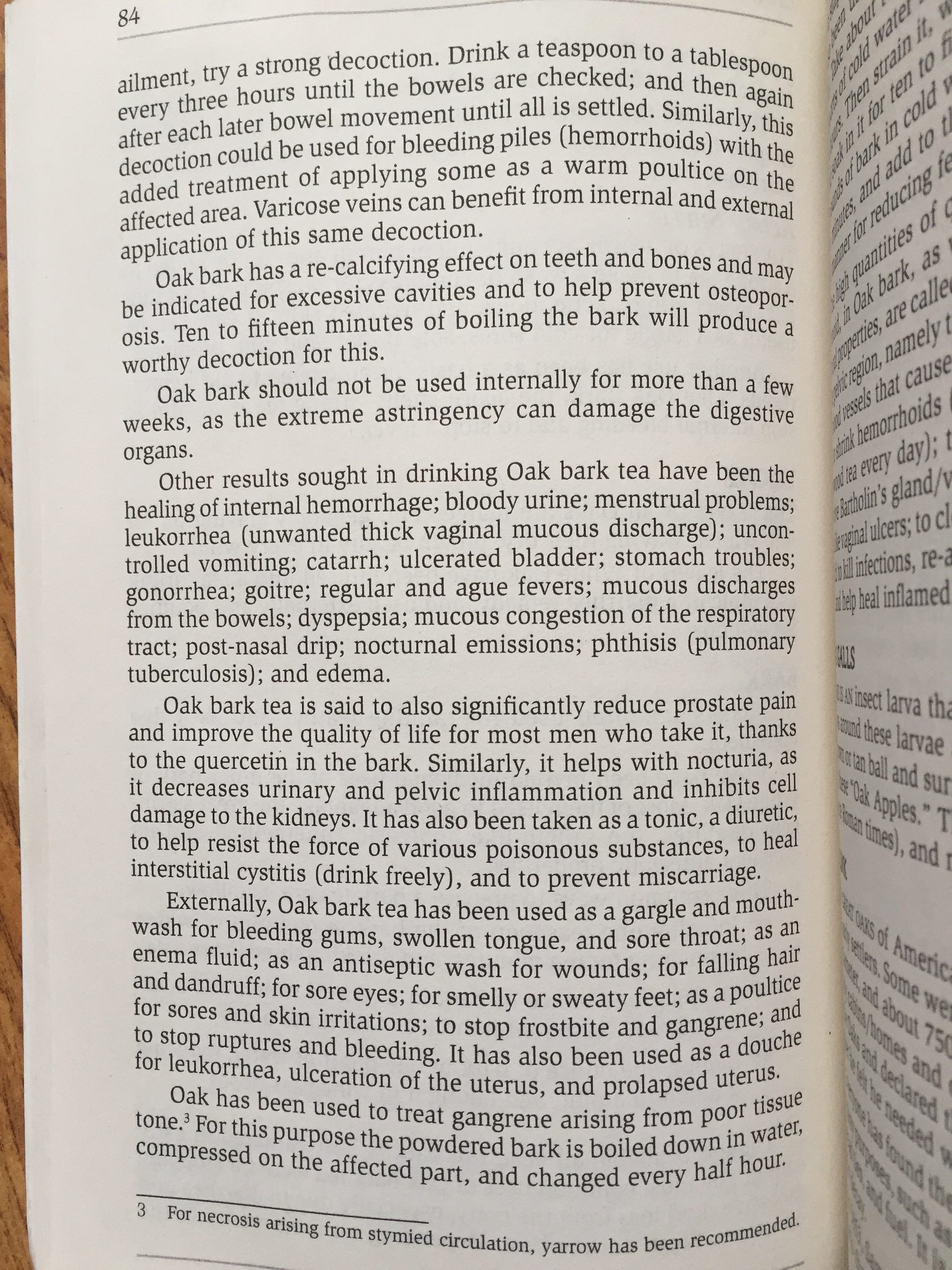

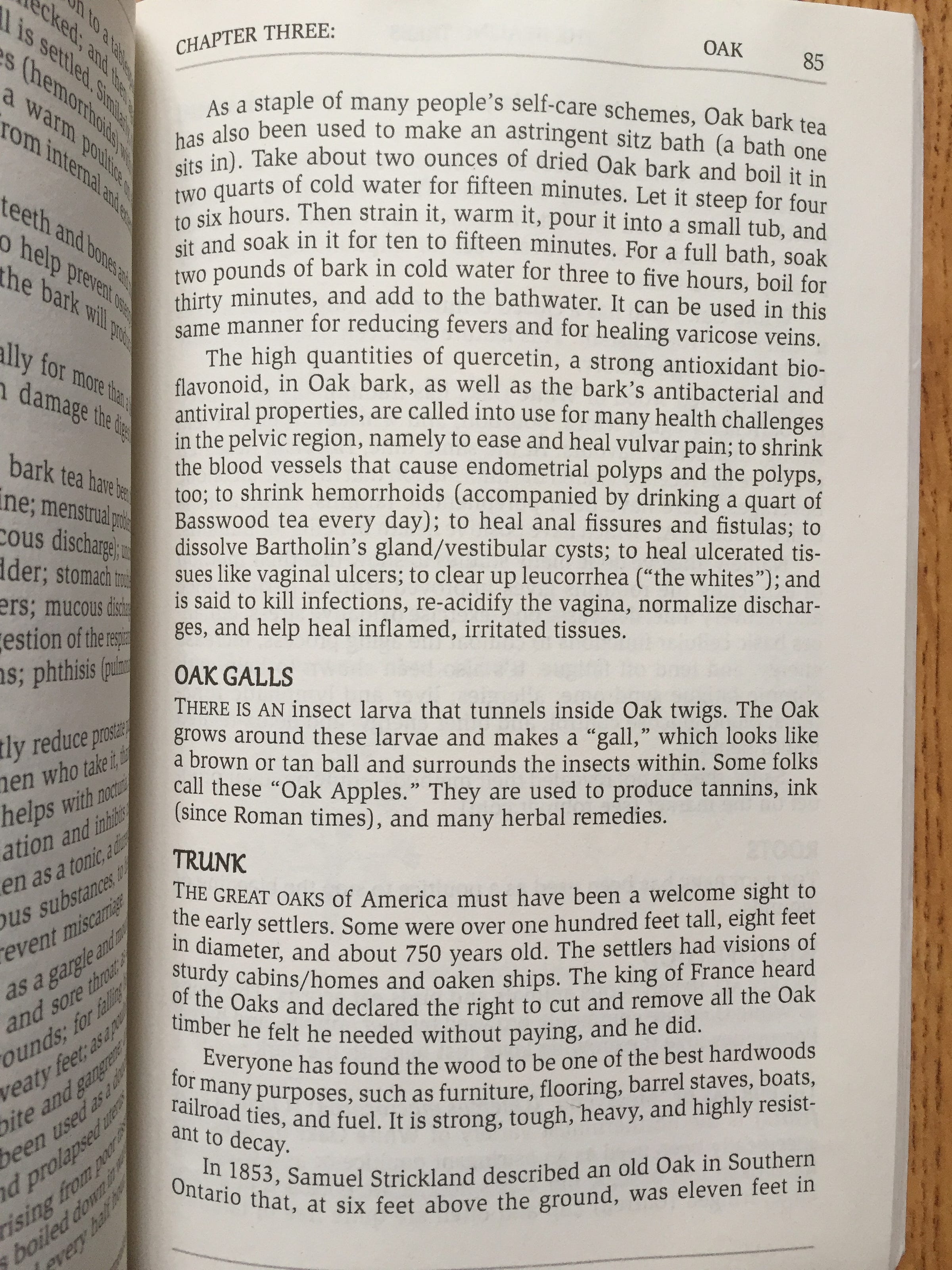

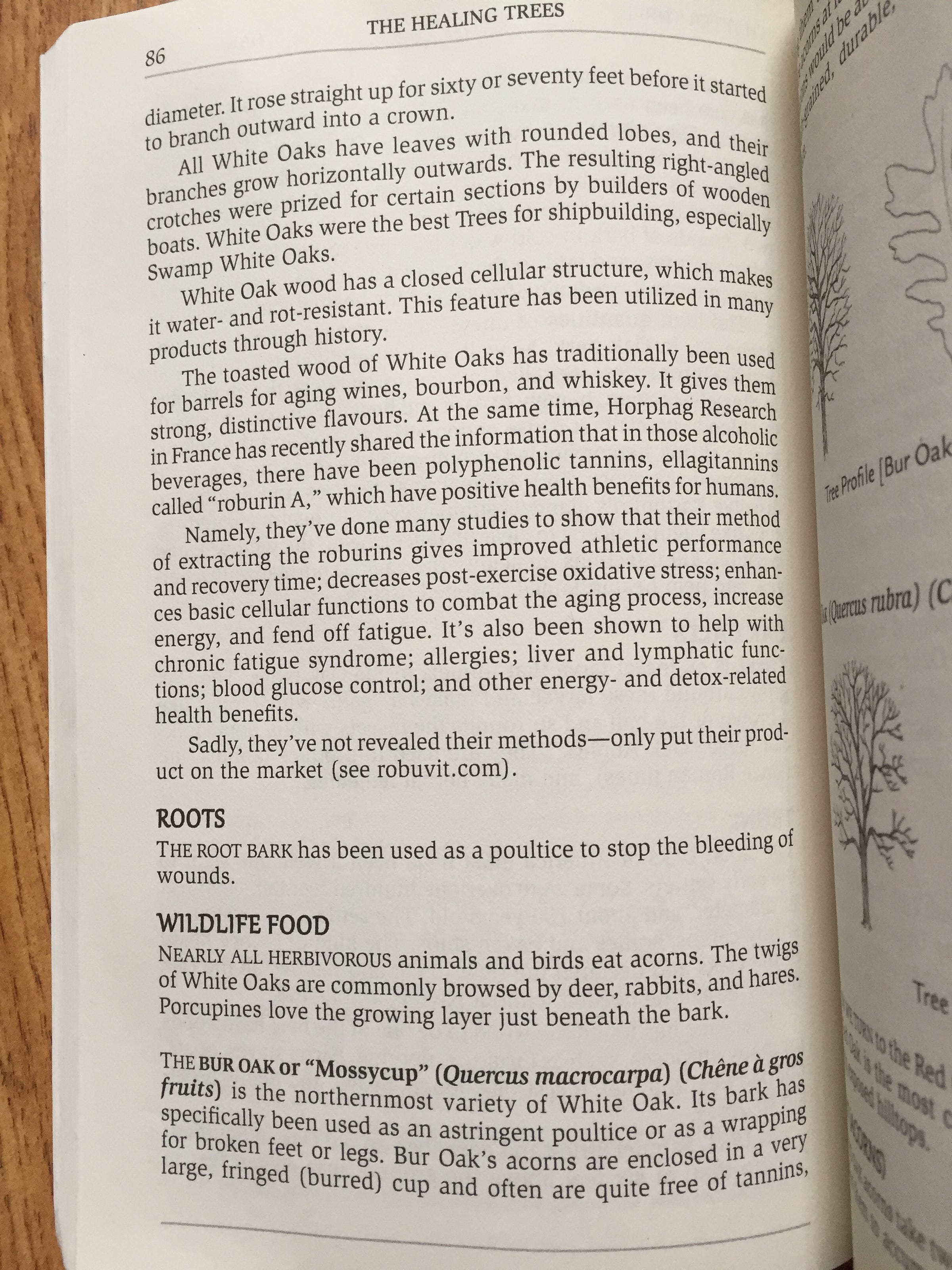

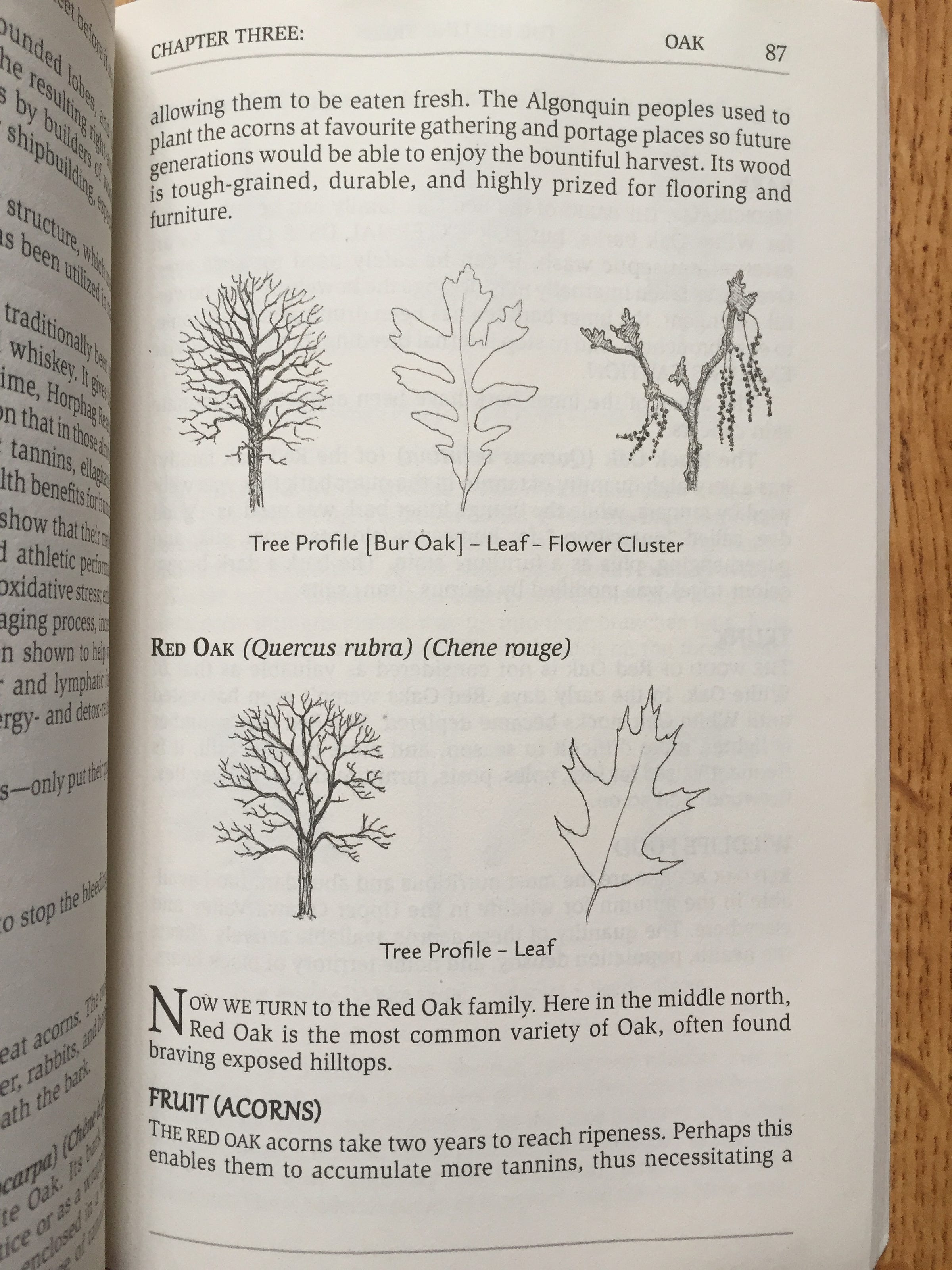

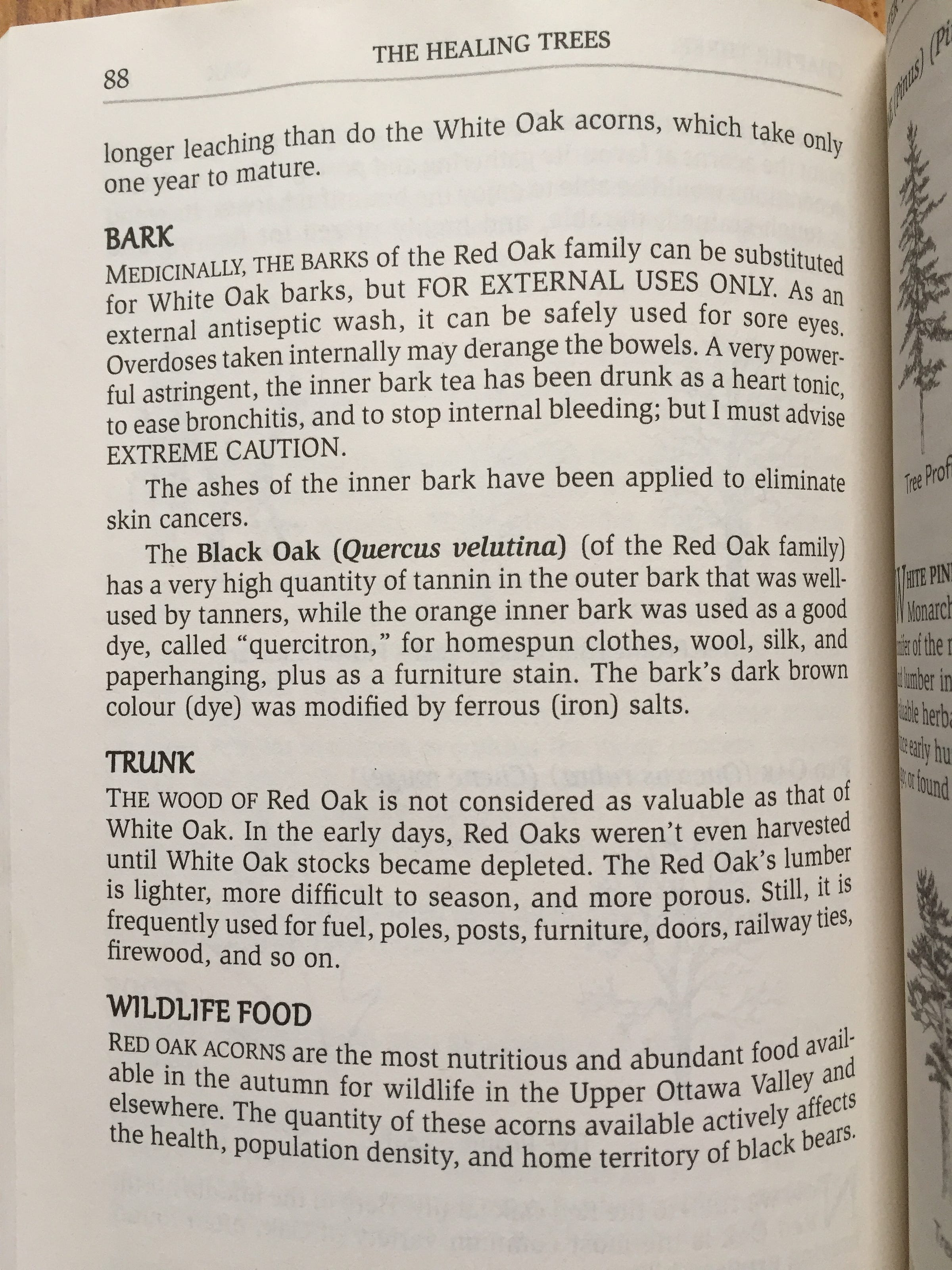

The following pics are from a book called The Healing Trees, by Robbie Anderman

Medicinal and Nutritional Benefits of Oak:

When you think of acorns, you might picture them as food for squirrels, but these little nuts are packed with nutrients that can benefit humans too! Let's dive into the vitamins, minerals, and macronutrients found in acorns.

Acorns are also an excellent source of:

Vitamin B6: Essential for brain health and metabolism.

Vitamin B9 (Folate): Crucial for DNA synthesis and cell growth.

They also contain a good amount of:

Vitamin B1 (Thiamine): Important for energy production.

Vitamin B2 (Riboflavin): Helps in energy metabolism and cellular function.

Vitamin B3 (Niacin): Supports digestive health and skin.

Vitamin B5 (Pantothenic Acid): Vital for synthesizing coenzyme A.

Minerals in Acorns

Acorns are an excellent source of:

Copper: Important for red blood cell formation and maintaining nerve cells.

Manganese: Essential for bone formation and nutrient metabolism.

They also have a good amount of:

Iron: Necessary for oxygen transport in the blood.

Magnesium: Supports muscle and nerve function.

Phosphorus: Helps in the formation of bones and teeth.

Potassium: Crucial for heart and muscle function.

Additionally, acorns contain some:

Calcium: Important for bone health.

Zinc: Supports immune function.

Acorns are also an excellent source of:

Fat: Provides essential fatty acids and energy.

Omega-6 Fatty Acids: Important for brain function and cell growth.

Carbohydrates: A primary energy source.

They also contain a good amount of:

Saturated Fat: Needed in small amounts for various bodily functions.

Protein: Essential for building and repairing tissues.

Health benefits:

Antioxidants: Acorns contain antioxidants like quercetin, catechins, resveratrol, and gallic acid. Antioxidants are compounds that defend your cells from damage caused by potentially harmful molecules called free radicals (Source).

Research suggests that diets high in antioxidants may help prevent chronic illnesses, such as heart disease, diabetes, and certain cancers (Source).

Acorns are rich in antioxidants like vitamins A and E, as well as numerous other plant compounds (Source).

One animal study noted that an antioxidant-rich acorn extract reduced inflammation in those with reproductive damage (Source).

Gut health: Acorns are high in fiber, which can help nourish beneficial gut bacteria. improve gut health

The bacteria in your gut play a key role in your overall health. An imbalance of these bacteria has been linked to obesity, diabetes, and bowel diseases.

Acorns are a great source of fiber, which nourishes your beneficial gut bacteria (Source).

Additionally, acorns have long been used as an herbal remedy to treat stomach pain, bloating, nausea, diarrhea, and other common digestive complaints (Source).

In a 2-month study in 23 adults with persistent indigestion, those who took 100 mg of acorn extract had less overall stomach pain than those who took a acorn capsule (Source).

Insulin resistance: Functional acorn cake may help improve insulin resistance in people with obesity.

Many of the healing properties of Oak can be attributed to the highly astringent plant constituents called tannins. Tannins bind with proteins in tissues, making a barrier resistant to bacterial invasion. They also strengthen tissues and blood vessels. They reduce inflammation and irritation, especially of skin and mucus membranes. Tannins play a key role in assisting healthy microbiota. They decrease intestinal permeability and support cultivation of healthy gut flora. Oak tannins can shift gut flora imbalances to thereby successfully treat long term chronic diarrhea in a single dose. Likewise, too much tannic acid can impair the ecological balance of gastrointestinal flora. Oak bark combines well with chamomile for aiding the digestive system. Oak bark can successfully treat antibiotic resistant strains of E. coli.

Oak strengthens poor digestion and is excellent for controlling loose stools. Decoctions of the inner bark are used to promote healing of bleeding gums when used as a mouthwash. Finely powdered dried inner bark can be used to control nosebleeds or can be sprinkled on skin ulcers to soothe and strengthen tissues, reduce swelling and prevent infection. A decoction of the leaf used as a compress helps to soothe and shrink hemorrhoids, varicose veins and bruises or may be used as a douche to treat vaginal infections. Bark decoction can also be used as a gargle to relieve sore throats. Oak leaf poultices help clear up skin problems such as rashes, irritation and swelling. Oak has also been used historically in the treatment of cholera and gonorrhea.

"The bark of the oak is a very powerful astringent; it stops purgings, and overflowings of the menses, given in powder; a decoction of it is excellent for the falling down of the uvula, or as it is called the falling down of the palate of the mouth. Whenever a very powerful astringent is required, oak bark demands the preference over every thing: if it were brought from the East Indies, it would be held inestimable."

- John Hill, The Family Herbal, 1812

Native American peoples use Oak to treat bleeding, tumors, swelling and dysentery. European herbalists use Oak as a diuretic and as an antidote to poison. The leaves can be employed to promote wound healing. Oak can also be used as a Quinine substitute in the treatment of fevers. Leaves may be used fresh for first aid in the field. They can be softened by immersing them in boiling water or steaming until limp. If boiling water is not available, the leaves may be softened by crushing them. Apply the leaves topically to the affected area as an antiseptic, soothing poultice to reduce swelling, skin irritation or bleeding.

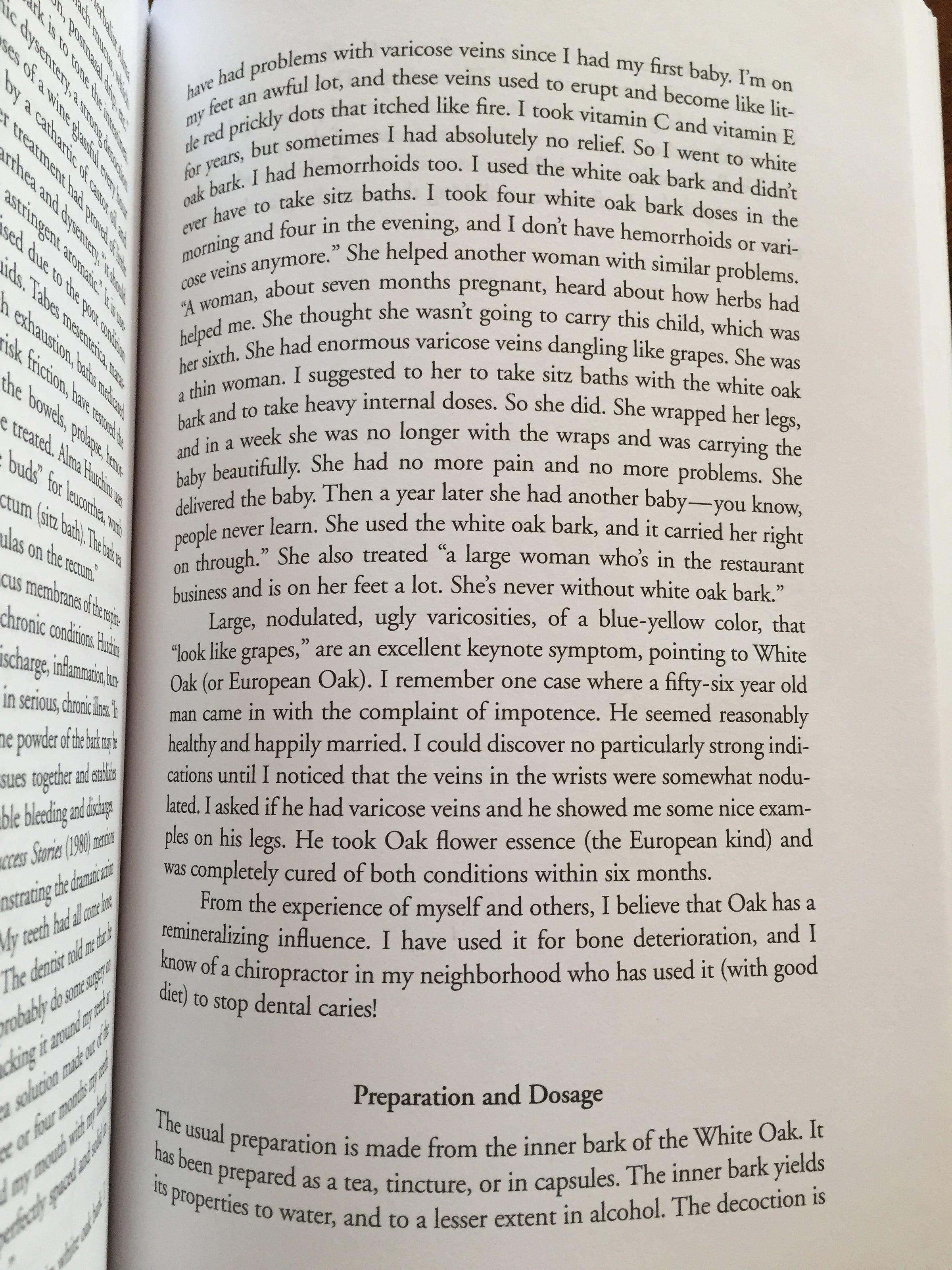

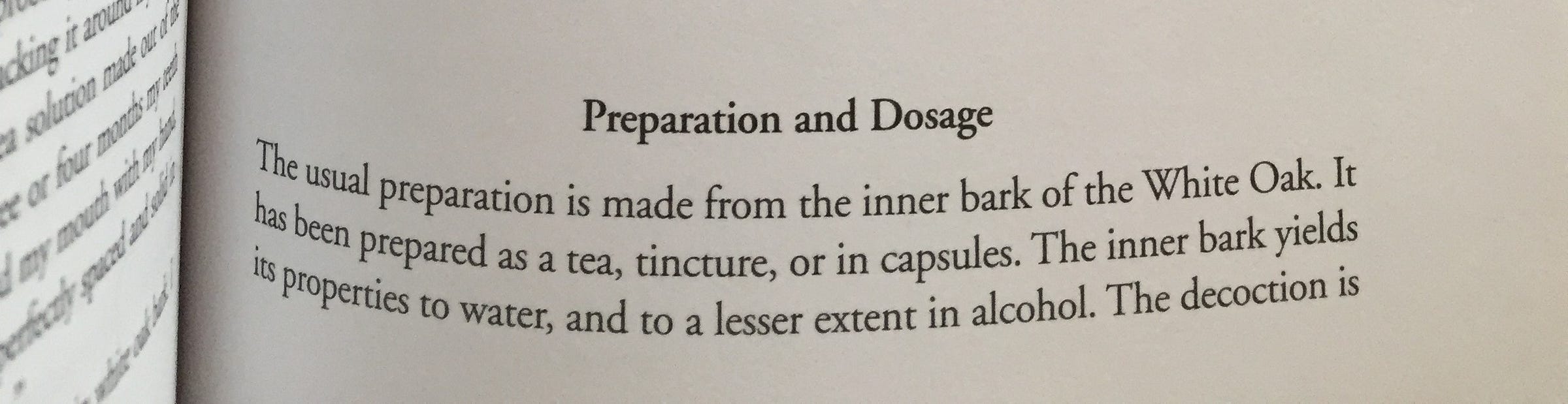

The following pictures are from “The Book of Herbal Wisdom: Using Plants as Medicines” by Matthew Wood.

I think the anecdotes regarding extracts from oak being capable of treating alcohol abuse to be particularly interesting.

Preparation & Dosage

Every part of the Oak tree has an important use, whether it’s for food, medicine, prayer or shelter. The parts of the plant that can be used for medicine include the inner bark, twigs, leaves, and galls.

Dried Leaves, Stems and Bark

Tincture 1:5, 50% etoh, 10% glycerin. Strong Decoction or Cold Infusion with dose ranges from 1 to 4 ounces up to four times a day, or applied topically as needed.

Fresh leaves

May be gathered for first aid as needed, and made into poultices.

Bark

The bark is higher in tannins than the leaves and much more astringent when harvested in the Spring. The ideal time to collect oak bark is before the trees flower at midsummer. Some say between March and June, others say between May and July. The differences will vary on the region and species of Oak.

Galls or oak apples

Oak apple or oak galls are the common names for the large, round, vaguely apple-like gall commonly found on many species of Oak. These oak apples range in size from 2 to 4 cm (1 to 2 in) in diameter and are produced upon the oak, not as fruit, but from the wounds made by an insect, typically moths. Fresh tincture 1:2 or dried galls same as leaves and bark, diluted for topical use; powdered galls can be mixed with a little hot water for topical use as a poultice.

Acorns

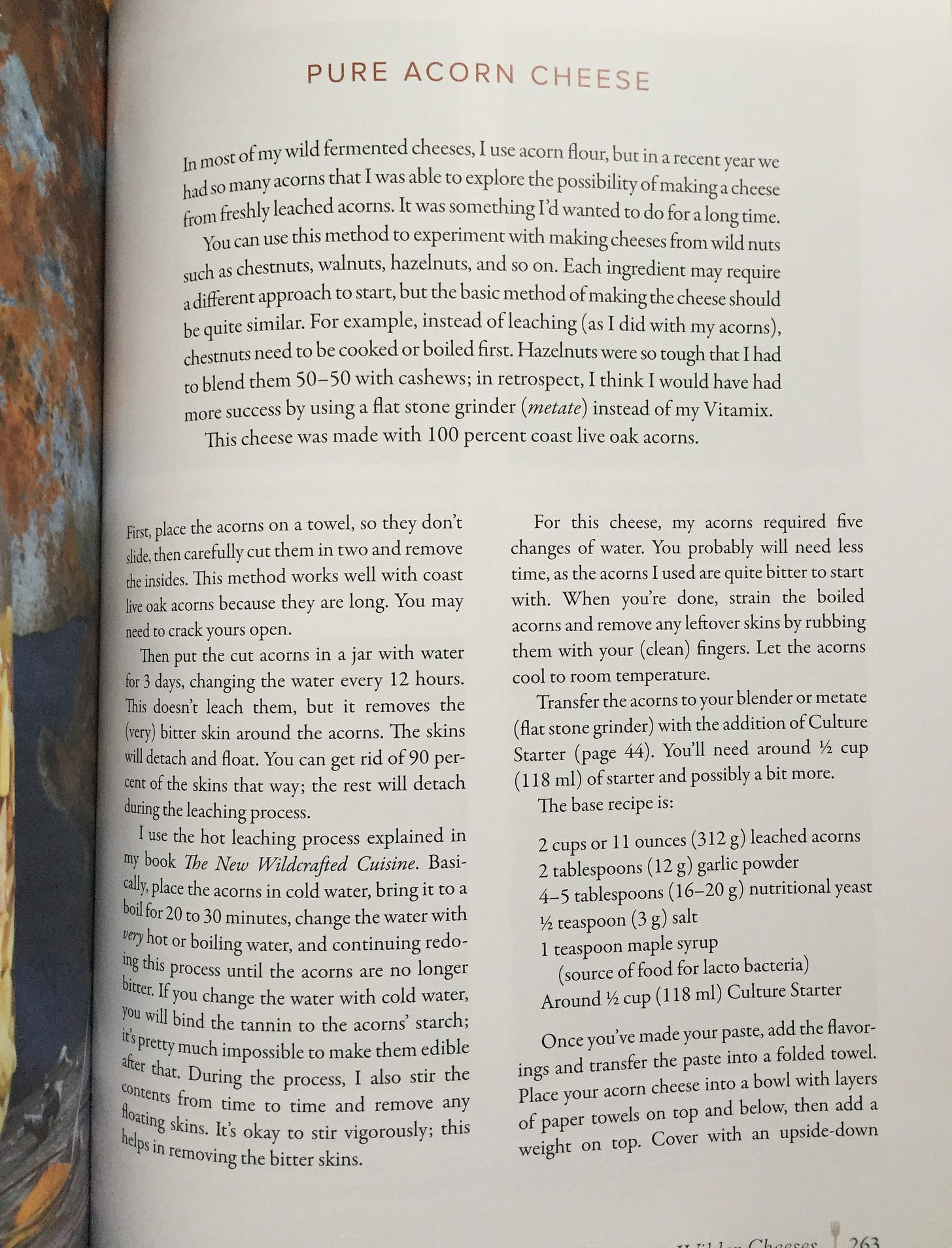

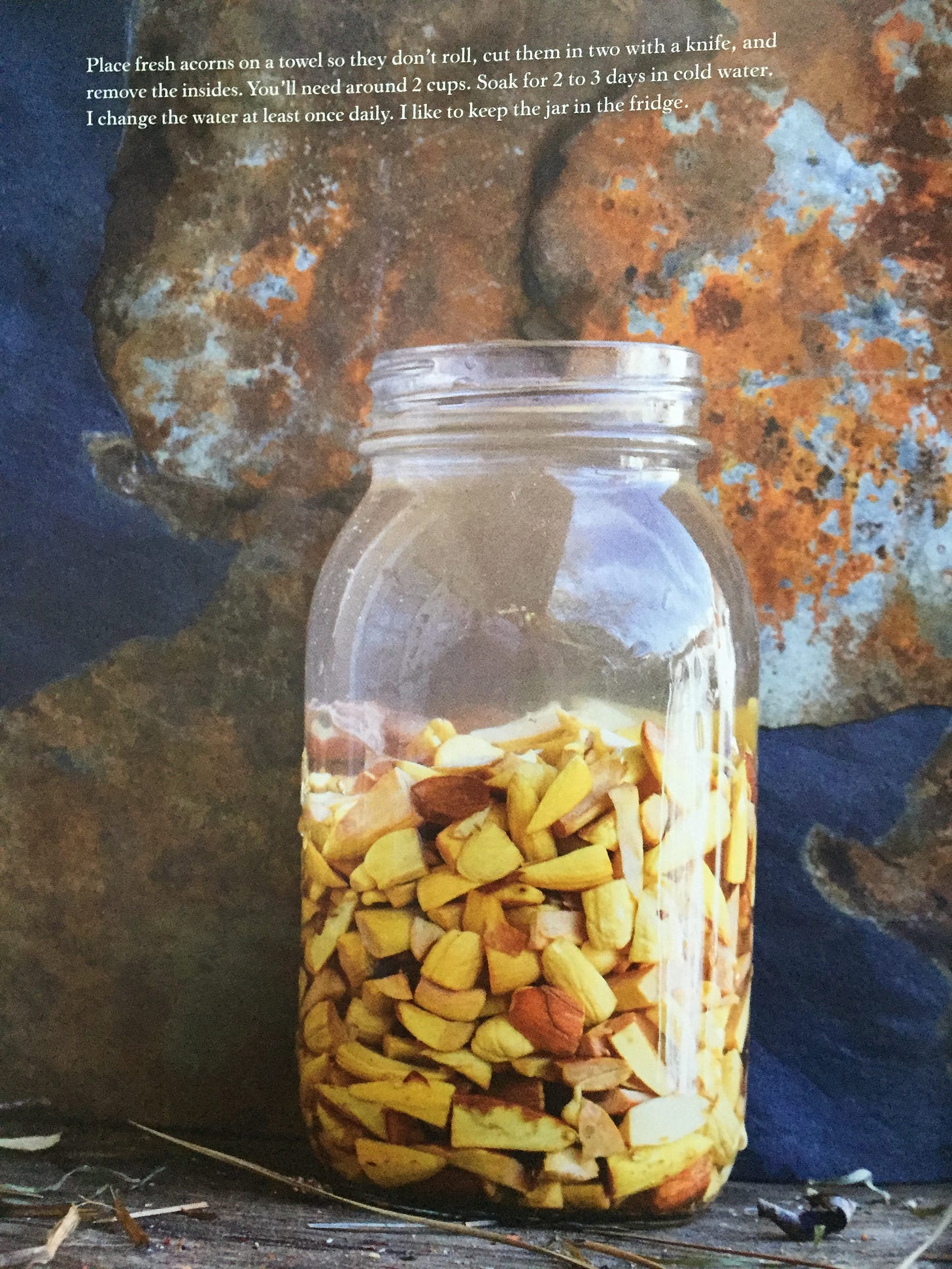

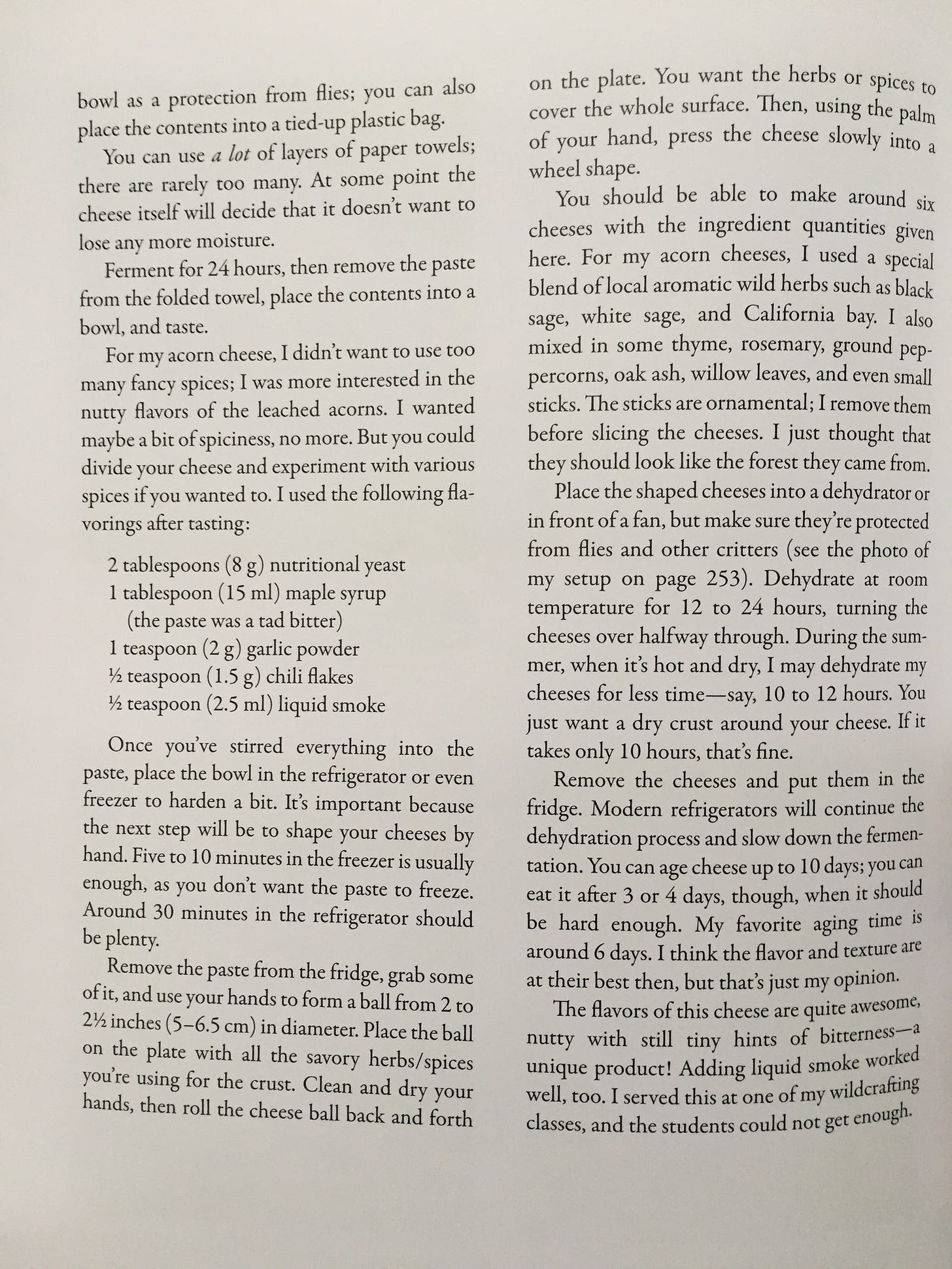

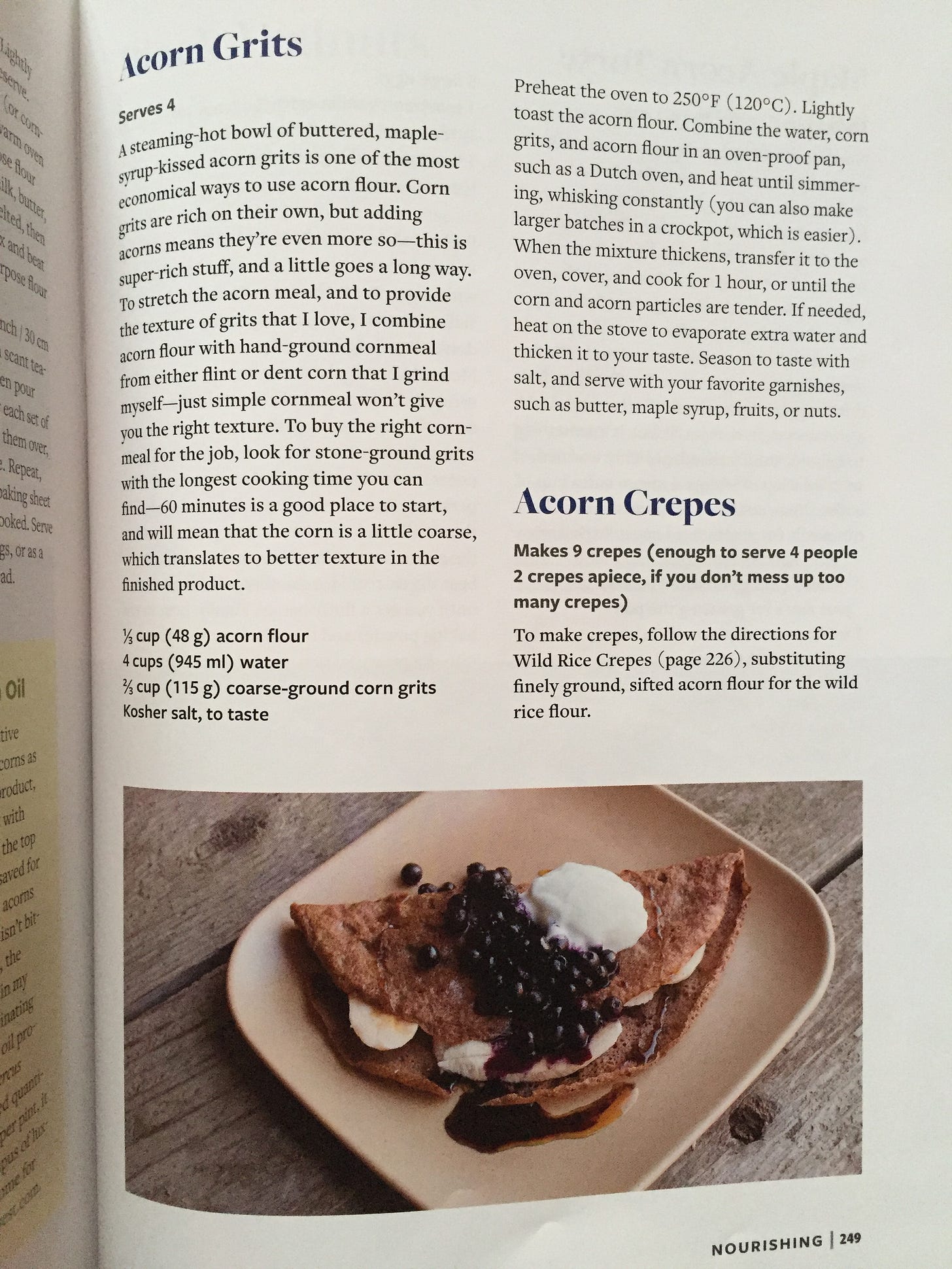

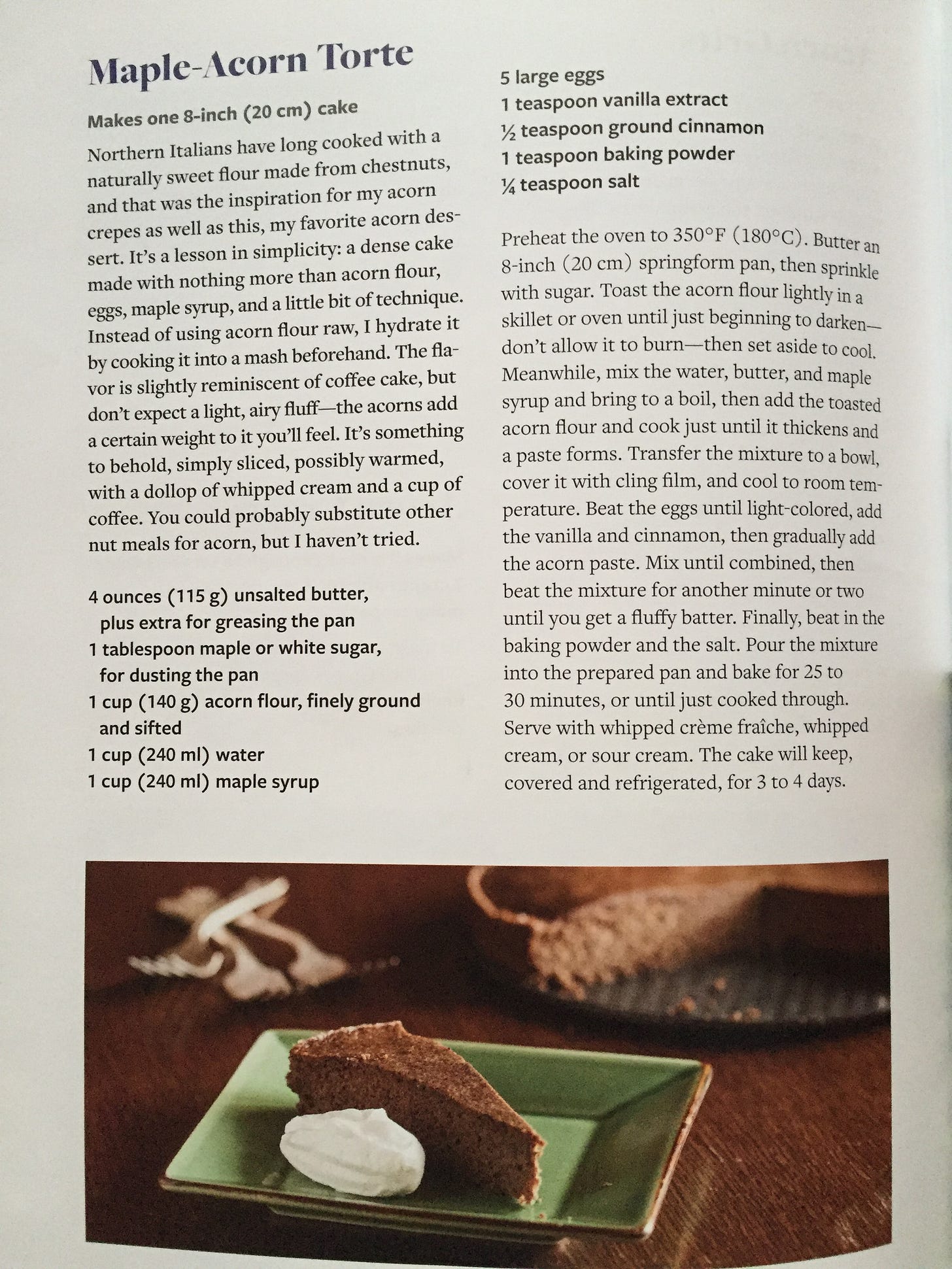

Gathered in the fall and are an excellent nutrient dense food source. Acorns are not produced until the tree is at least 40 years old. Peak acorn production usually occurs around 80 – 120 years, and some trees can live longer than 500 years. One large oak tree can produce 1,000 pounds of acorns in a year. There is lots of variation among Quercus and Lithocarpus species members. Some are much richer in tannins, while others are a bit milder in their astringency. Acorn foragers find astringency levels among species groups to vary greatly. Acorns are a nutrient dense food. They are lower in fat and sugars then many other nuts. Acorns provide about 125 calories per ounce. They are rich in polyunsaturated fats, vitamin B6, copper, manganese, phosphorous and potassium. Raw acorns contain a high amount of tannins. Tannins are phytochemicals that have a bitter taste and are typically extracted by the leeching process that turns acorns into food. While we prefer to avoid large consumption of tannins in our food, tannins have an astringent property which have significant medicinal uses. There are many methods for leeching and processing acorns into food. In fact there are so many ways to approach acorn eating that entire books have been written on the subject.

Flower Essence

Oak is a part of the original 38 flower remedies created by Dr. Edward Bach. It is used for those with feelings of despondency and despair. Those who hopelessly struggle to get on with daily life, despite their nature to fight on. When such cases of chronic illness interferes with the ability to perform basic duties or help others oak essence can help to shift the paradigm. It grants the ability to endure and carry on during tough times.

History and Cultural Relevance of Oaks:

Cultural history illuminates (at least) 11,000 years of lifeways of civilizations across temperate regions have been built around acorns and Oak trees.

Here in the Eastern Woodlands of Turtle Island tree typically grows mixed in with other canopy hardwood species but there are places in Ontario and Quebec (as well as many locations south of us) where highly concentrated old growth stands of Swamp White Oak, Burr Oak and Hickory exist along side unnaturally high concentrations of other choice food and medicine producing tree species indicating intentional indigenous agroforestry design.

Pollen samples from the soil indicate these manmade food forests were created in various parts of the Eastern Woodlands of Turtle Island between 800-1500 years ago and many of them persist (and have become self-propagating and self-perpetuating food forests) even with the original indigenous horticultural architects of said manmade forests having been removed from that land for centuries now in some cases.

These places continue to produce an unusually high amount of food and medicine (that is well suited for the human diet and health) even though the original forest gardeners are no longer able to do their annual controlled burns and careful interplanting of key companion tree species (as pollen evidence indicates they engaged in for hundreds of years prior to European Contact) their forest gardens are still producing abundant food (for those capable of recognizing it) today.

The Jesuit Relations offers first hand observations by missionaries that were interacting with the Huron and Wendat people here what is now called Ontario in the 1600-s and they offer accounts of how the indigenous people lived in communities with longhouses and fields of corn, squash, beans and medicinal herbs on the periphery of said communities, and then further out those people tended what the Jesuit priests described as “well manicured orchards” that were spacious, composed of multiple nut and fruit producing species and allowed for the people who the priests described as “savages” to easily collect baskets brimming with nuts and fruit to bring back to their communities.

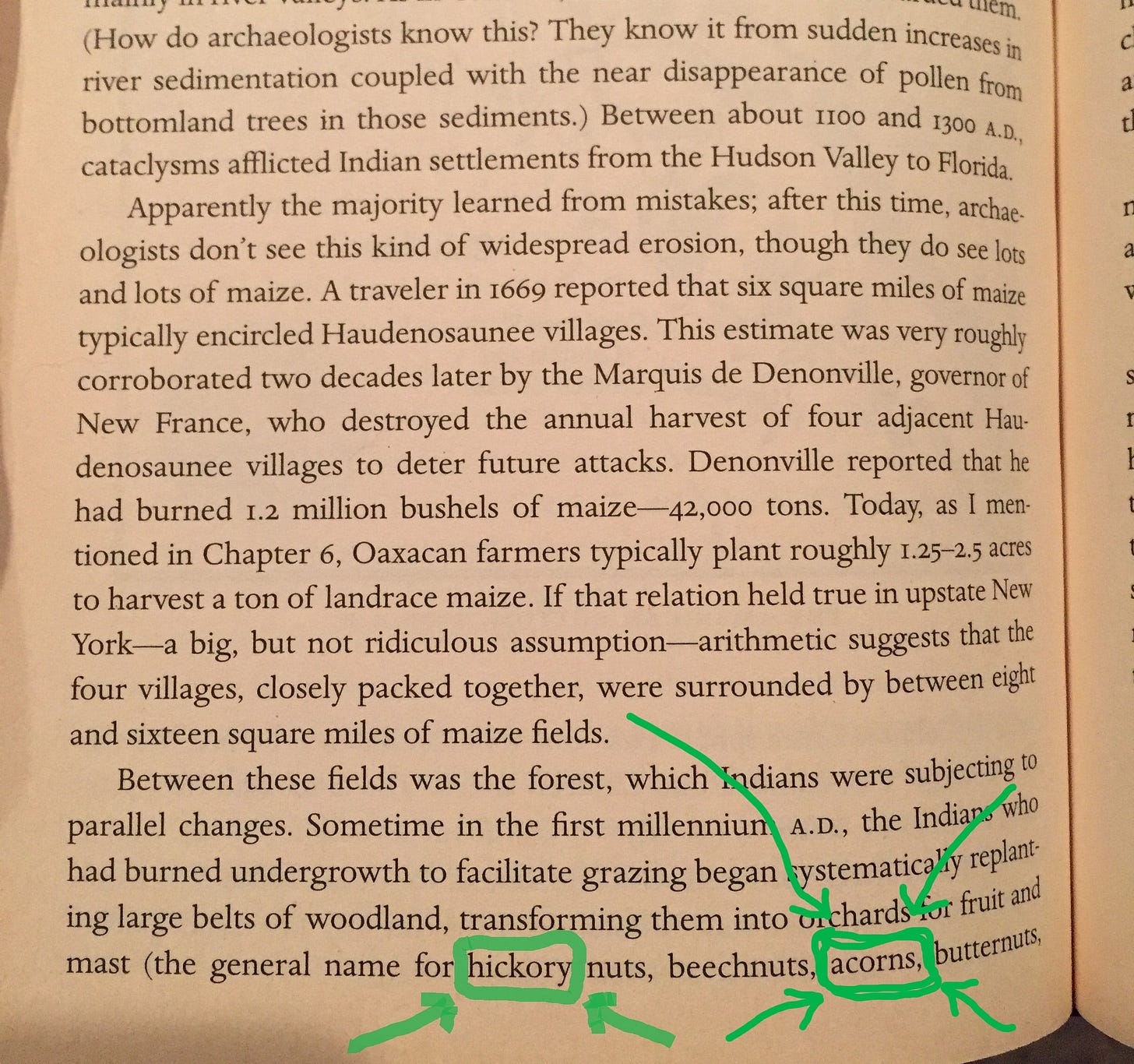

In 1491: New Revelations of the Americas Before Columbus by Charles C. Mann you can find other accounts of well tended to “orchards” and forest gardens near Cape Cod that were tended to by the people of the Wampanoag Confederacy. (a picture of one such page from the above mentioned book is shown below)

London, Ontario was once the homeland of an Iroquoian-speaking people that the Huron called the Attawandaron and the French called the Neutrals. Their homelands extended all the way up the highway 401 corridor from Sarnia to Guelph, along the same path as the Deshkan Ziibi. These peoples had an alliance with the Mississauga Nation. This distinct group of Mississauga peoples spoke a dialect of Algonkian and thrived primarily at the mouths of the rivers leading to the Great Lakes.

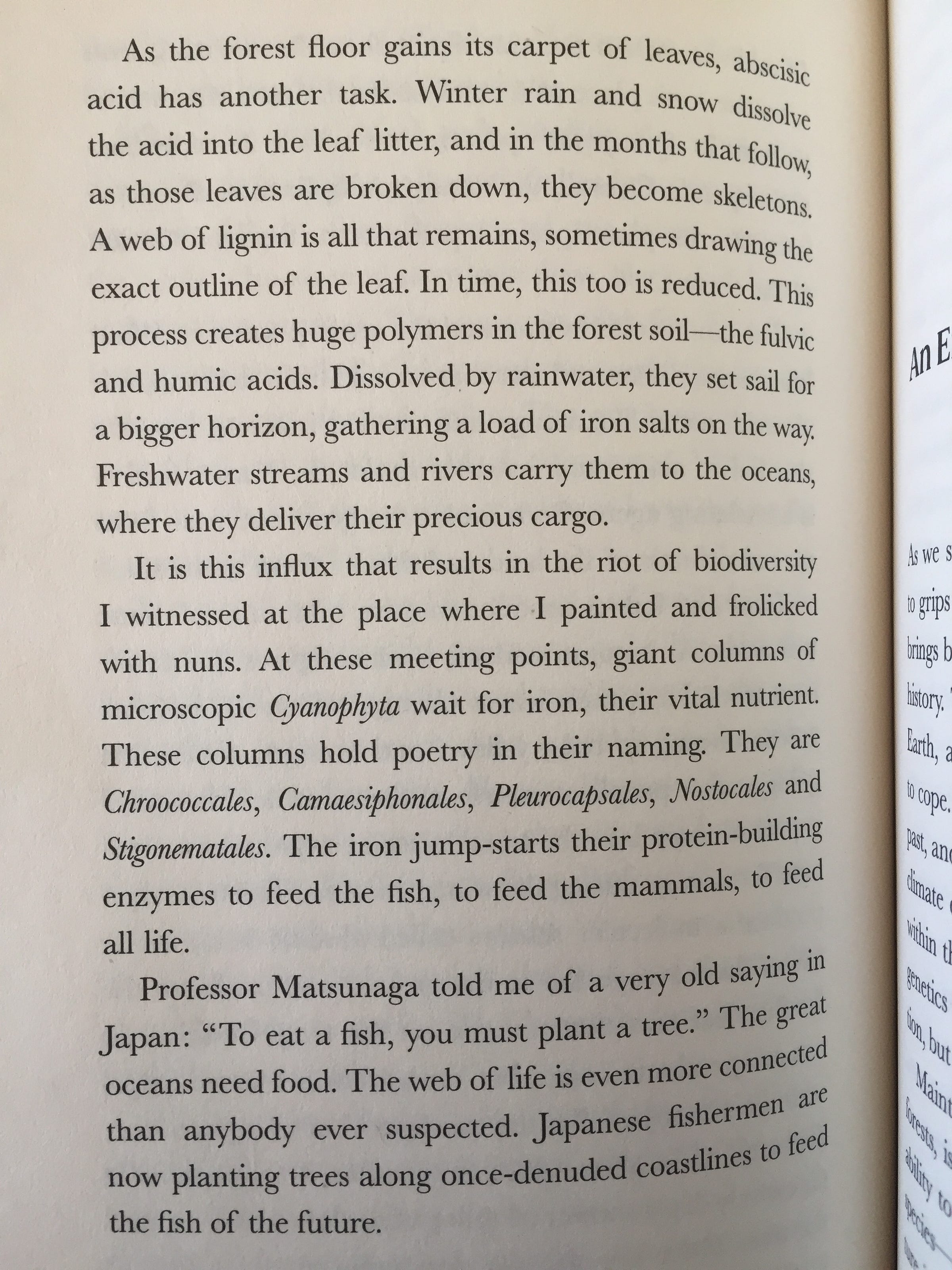

Sometime around 1,200 years ago, this whole region was gradually converted to an Oak/Hickory Savannah food forest, accented by prairie grasses and wetlands, by design. A food forest is essentially what it sounds like. It is a strategically designed habitat that focuses on building up several layers of the ecosystem to ensure food for all parts of that ecosystem throughout each of the seasons, with a long-term vision for generational thriving.

Envision this for a moment: Over the course of time, specialists would have begun to map the land through storytelling, not on paper, and in turn share those stories amongst their community members so that a general map of the region becomes embedded within the consciousness of all members of the civilization.

These specialists would have been tracking the ecosystem’s progress, in all its diversity, including weather patterns, mineral locations, plant and tree growth cycles, fungi growth cycles, bird migrations routes and nesting patterns, mammalian den sites, fish spawning locations, reptile egg laying sites, and arthropod numbers, over time, to name only a handful. Based on pre-existing features of the land — such as wetlands, rivers, ground elevation levels, microclimates, and migratory patterns of some of the beings listed above — spaces would be selected where human habitation could be established.

I tend to see this manmade or ‘managed’ forest ecosystem as having six or seven layers by design. At the bottommost layer I think of root plants like wild carrot, sassafras, wild Canadian ginger and trout lilies. The next layer, though it could also be considered the underlayer, is the fungi and mycelium, things like turkey tails, oyster, giant puffballs, and chaga.

The next layer is the ground plant layer and throughout each season there are many that rise up. Not all of these are edible specifically, but all are medicinal. Think of strawberries, trillium, black cohosh and wild leek. Next you have the bush/small tree plants like raspberry, hazelnut and cedar.

As we continue upwards, the next layer is the medium-sized trees like Pawpaw , Saskatoon berry and highbush cranberry. Finally, the uppermost layer is the heavy nut producing trees like Swamp White, Burr and other Oaks, Sweet Chestnut, Shellbark (aka Kingnut) and Shagbark Hickory, Black Walknut, Butternut, Chestnut, Tulip Tree and White Pine.

On the edges of the Food forest that transitioned into annual cultivation spaces for three sisters you would have Sumac, Elderberry, Anise Hyssop, Echinacea and Milkweed.

Hickory and White Oak were principal to the ancient food forests of southern Ontario, based on the abundance of nuts it produces each season and the limited amount of processing required to eat them.

Most of these foods and medicines must be enjoyed and processed at a specific time during the season, and all this ecological knowledge would have become embedded in the action-based education system, so training would have occurred for community members for the action of controlled burns.

Indigenous peoples were in possession of deep ecological knowledge passed down culturally through story, ritual, and tradition. Through ongoing symbiotic interactions with the plant beings around them, over time species increased in abundance. With the advent of integrated, ecological shifting cultivation systems, indigenous peoples were able to transform the landscape like never before.

The existence of cultivated quinoa-like chenopods in Ontario 3,000 years ago is evidence that an integrated shifting cultivation system existed already in the region before the Three Sisters cultural complex became dominant. Before the Three Sisters, indigenous people in the northeastern woodlands (modern day southern and central Ontario) were likely cultivating the seed crops chenopod (Chenopodium spp.), erect knotweed (Polygonum erectum), and sumpweed (Iva annua) as annual staple grains, during the initial stages of a cycle that evidence indicates included agroforestry (including cultivation of trees like Oak and Hickory) in the later stages. If you would like to read more about these the work by Natalie Mueller on the “Lost Crops” is worth checking out.

So agriculture, from polycultures of annual crops, transitioning to more advanced 50 plus year cyclical food forest plantations (which became permanent self-perpetuating food and medicine production systems as part of a highly advanced regenerative farming system had been being implemented on the land where I now live for literally millennia by indigenous horticultural experts.

Here are some more accounts of well tended to “orchards” (actually advanced regenerative agroforestry polycultures, aka “forest gardens” or “food forests”) in 1491: New Revelations of the Americas Before Columbus by Charles C. Mann. This time the accounts are regarding the Food Forests of the Haudenosaunee people from the area where I live now in the Eastern Woodlands:

So this land where I live used to be filled with highly advanced forest scale farming systems that were apparently indistinguishable from an intact climax forest ecosystem to the colonists (or at least regarded with as little respect as the non-tended “wild” Carolinian Forest that once existed here from horizon to horizon.

Here, today, in what is now called southern Ontario in the Eastern Woodlands of Turtle Island 99.9% of the primary Carolinian Forests and old growth food forests that once dominated the landscape from horizon to horizon have been cut down in the last 150 years.

What was once a thriving forest ecosystem with Paw Paw (Asimina triloba) groves thriving underneath a 100 foot high plus super canopy of Butternut, Eastern White Pine, Sycamore, Black Walnut, American Beech, Shellbark (“Kingnut”) Hickory, Shagbark Hickory, Sugar Maple and Tulip trees with large tracts of anthropogenic food forest mixed in is now mostly GMO soy and corn fields, strip malls, hydroponic greenhouses, factories and concrete. Based on my research and field expeditions I estimate that no more than one tenth of once percent of the original forests (untended primary Carolinian Forest, which stretched from horizon to horizon as well as anthropogenic old growth food forests, which used to cover tens of thousands of acres here in Essex county alone) still exist today.

The most aggressive and arrogant deforestation of Southern Ontario (peaking in a clearcutting frenzy about 120 years ago) was in large part instigated and encouraged by the “Dominion of Canada” government putting out advertisements offering “free land” to anyone that would clear the forest, sell the old growth trees to the military for their ship masts and grow a monoculture annual crop on the land. The government propaganda conditioned settlers to view the forest as an “obstacle” and something that needed to be cleared to bring “order” to the land. One of the main motivations behind that push was to get people to do the dirty work of chopping down the 120 feet tall plus 500 year old plus Mother tree Oaks, elder Kingnuts, and 250-400 year old white pine to supply British with masts for the Navy to be able to perpetuate it’s war racketeering operations.

Of course, it was not “free land” being benevolently gifted to poor up and coming emigrants to help get them started (as the propaganda posters implied) is was blood soaked stolen land, and land that had been carefully tended for generations to create a multilayered self-perpetuating resilient and diverse food production system that the European colonists were to ecologically illiterate and arrogant to recognize for what it was.

I share this to illustrate how the vague government propaganda inculcated idea that many people have in their minds about European industrial civilization “improving” life here and “developing” the “natural resources” or “making use of land that was just going to waste sitting there for agriculture” is a flat out lie and a fallacy.

This land was already being tended with purpose and the food cultivation system that was being implemented here for well over a thousand years prior to those clear cutting operations was far superior in every way to modern farming practices.

Similar stories of short sightedness and greed can be found of that time period to the south of us in Michigan.

One of the most vivid description of the Cultural Forests of Eastern North America I have encountered so far comes from an early pioneer from the state of Michigan, 1884. What he tells is a sobering testimony to what has been lost, but if we begin to remember, we can let it be so again:

“In the forest we found the whole family of oaks, of the Michigan family, some twelve different kinds, and among them the burr oak, bearing an acorn good to eat, and on which hogs would fatten. In the timbered lands were the new trees called the basswood, of which the best timber for building was made; and the black walnut, more valuable than cherry for cabinet work. It also bore a large and very rich nut, and with it were the whole family of the hickories, all bearing good eatable nuts. Besides these were the butternut, the beechnut, and the hazelnut, all bearing an abundance of their fruit. Throughout the woods we saw the grape-vine hanging from the trees laden with its fruit. We saw vast thickets and long rifts of blackberry bushes lately burdened with their tempting berries. And we were told that the woods and hillsides and openings, in their season were fairly red with the largest and most delicious strawberries, while the wild plum grew along the small streams, the huckleberry and the cranberry on the marshes, and the aromatic sassafras was found throughout the woods. The annual fires burnt up the underwood, decayed trees, vegetation, and debris, in the oak openings, leaving them clear of obstructions. You could see through the trees in any direction, save where the irregularity of the surface intervened, for miles around you, and you could walk, ride on horse-back, or drive in a wagon wherever you pleased in these woods, as freely as you could in a neat and beautiful park.”

“Pioneer Annals” by A. D. P. Van Buren, in “Report of the Pioneer Society of the State of Michigan”, Volume 5, 1884, pg. 250.

Just like here in southern Ontario, those ancient food forests in Michigan are all chopped down now except for fragment remnants.

Evidence indicates that regenerative agroforestry designs were being implemented by indigenous people of the eastern woodlands of Turtle Island 1,500 years ago. Some of the results can still be seen today, examples of the robust, anti-fragile subsistence systems practiced by indigenous Iroquoian peoples. If the indigenous cultural landscape could be seen four hundred years ago from a bird’s eye view, it would be a shifting mosaic of food and medicine producing anthropogenic ecosystems fluidly melding one into the other, and incorporating the full spectrum of diversity of species and habitat types.

When many people seek to learn about indigenous food cultivation systems of Turtle Island, they end up reading about the famous Three Sisters. Three Sisters appear consistently in the archaeological record as an integrated polyculture, starting in about 600 AD. The people of the Haudenosaunee Culture are thought of as the first farmers in the northeast, though the evidence now indicates that is an over-simplification given how that story says nothing about the ancient food forests that those same cultures created.

The indigenous inhabitants of this land were often selectively burned woodlands every autumn or early spring. Burning would have kept back the underbrush of fallen branches and brambles. Burning would have also eliminated bushes or kept them in small, coppiced forms where the tops are frequently killed only to resprout each season from the living roots. The burning would kill the fire-sensitive saplings of ash, elm, and maple, conserving the wide-open nature of an oak-hickory forest. Not only are shagbark hickory and bicolor oak trees resistant to damage by fire, but their deep taproots allow them to resprout vigorously in case a small, sensitive seedling tree should be accidentally incinerated.

In the wake applying fire selectively to the woods, in areas of full or patchy sunlight the groundnuts would form into a nearly solid groundcover, like poison ivy but edible, ready to be dug for sustenance at any moment of the year. The earthbeans Amphicarpaea bracteata would also form a solid groundcover but being more tolerant of deep shade, these may be found deeper within the forest.

The groundnuts and the earthbeans fix nitrogen, and the annual fires would decrease nut weevil pests, raise the soil pH toward neutral, and in the process increase the calcium and phosphorous available to the trees. This funnels important macronutrients needed for seed and nut development to the shagbark hickories and bicolor oaks, lending support to their annual-bearing potential and consistency, and positively influencing the size and abundance of the nut harvest.

When the Gayanashagowa or Great Laws of Peace of the League of Iroquois Nations were established along the shores of Lake Onondaga a thousand years ago, they brought an end to relentless warfare experienced by the early Iroquoian peoples. It is thought that the people of the Owasco Culture were those peoples. The Great Laws of Peace were revealed by the Great Peacemaker and translated through his spokesman Hiawatha, in the home of the Mother of Nations Jigonhsasee. The treaties served to establish a democratic confederacy known as the Haudenosaunee, or the “people of the longhouse.” To this day it is one of the longest running democratic societies in the world.

Like the longevity of the Haudenosaunee Nations, what is amazing to me is that in several places evidence of advanced food forest design (regenerative agroforestry farming systems) such as north of us on the shore of Lake Huron/Georgian Bay or beside Lake Owasco) centuries later, in tact tracts of an agroforestry system are still present, seen by the present-day composition of the forest.

This is a forest filled with staple foods, from root to crown: groundnut to hickory nut to acorn. This existence of this legacy agroforest paints a vivid picture illuminating how some of the first peoples of Turtle Island had mastered highly advanced and truly sustainable farming methods long before the arrival of the Europeans.

Each one of the scattered dense (non-linear) Swamp White Oak, Burr Oak and hickory stands I have studied locally (and north of us near Lake Huron) occupies an area ideal as seasonal camps for hunting, fishing, and gathering. Hickory is a species that requires a lot of calcium in order to thrive, so it is found in restricted habitats above floodplains and below slopes, where alluvial soils rich in nutrients like calcium get deposited. In many of the disjunct populations, the stands of Swamp White Oak, Burr oak, Shellbark, Shagbark are isolated, sometimes hundreds of miles away from the next stand. Several of the populations are associated with known archaeological sites. Here in southern Ontario, it is no different.

The unavoidable conclusion is that their seeds were brought here and planted by the human inhabitants of this place.

Bur oak (Quercus macrocarpa) growing alongside anthropogenic ancient Shellbark and Shagbark hickory as well as Kentucky coffeetree (Gymnocladus dioica) are still found growing here as well. This bur oak – hickory association is not novel, but a repeating theme throughout the overlapping range of these two species. And like our bicolor oak – hickory duo, the bur oak fulfills a similar niche as the bicolor oak, (as well as the chinquapin oak) thus they can be considered interchangeable both culturally and ecologically (and nutritionally).

The Kentucky coffeetree, a nitrogen-fixing leguminous tree, bears large bean pods with edible seeds. The Kentucky coffeetree fulfills a similar niche as the honey locust (Gleditsia triacanthos). These along with pawpaw groves are all found growing in unnaturally high concentrations in archeologically confirmed ancient indigenous community areas in Ontario, New York and elsewhere.

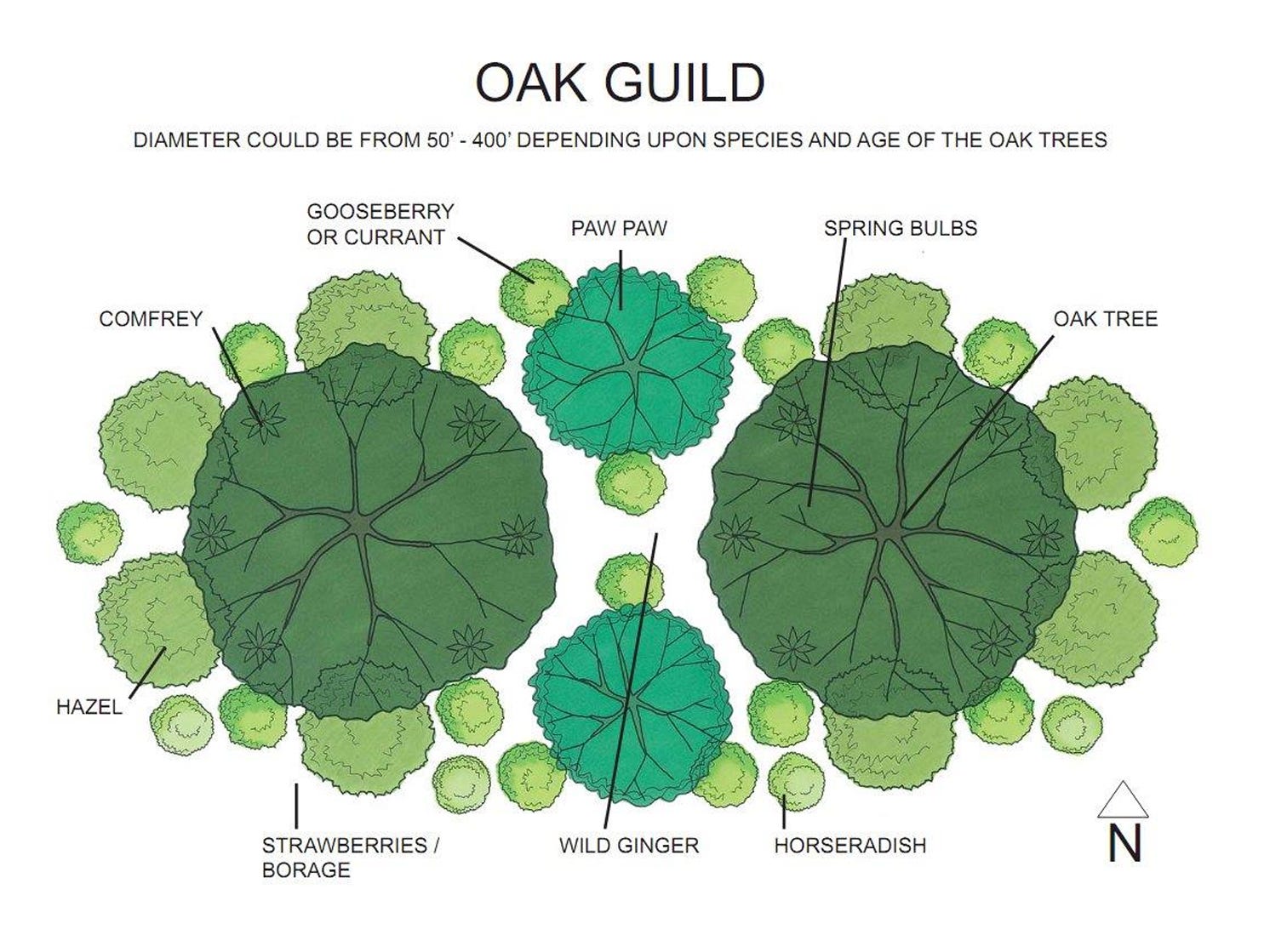

Like the Kentucky coffeetree, the honey locust bears large bean pods with edible seeds as well as an amber-colored sweet flesh inside the pods that is rich in sugar and very sweet to the taste. Honey locust pods, which sometimes contain up to 38% sugar by weight, is reminiscent of tamarind, and could be considered culturally analogous. An association between honey locust populations and native settlements has been noted before. Both the Kentucky coffeetree and the honey locust fulfill similar niches culturally and ecologically, and so they may be considered interchangeable. As nitrogen-fixing trees, they play important supporting roles to the other trees in the forest. The polycultural trio of oak, hickory, and bean tree appears to have been seen as playing a role similar to that of the Three Sisters. To use the language of permaculture, this is a guild.

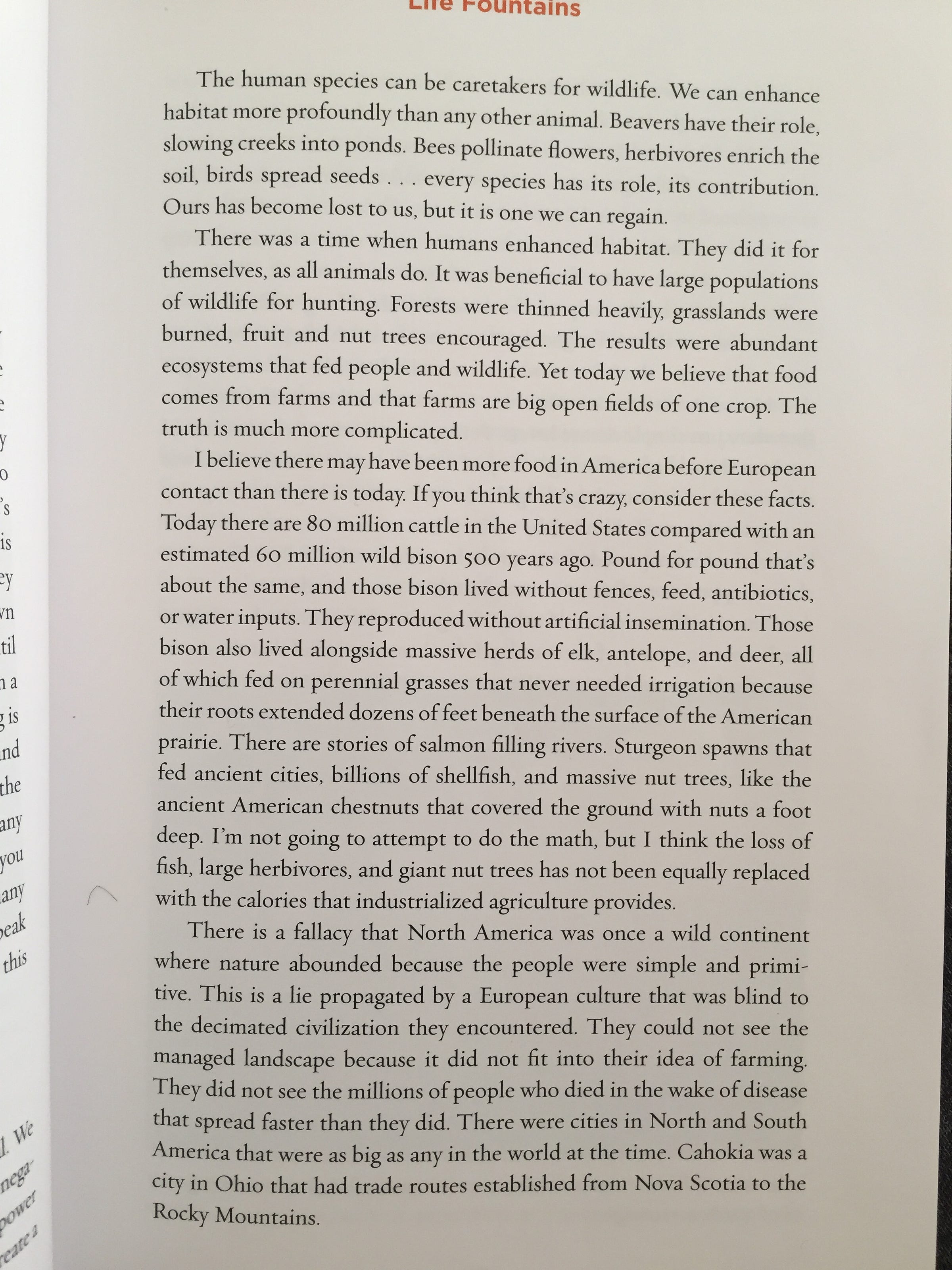

“From the forest, they derived all their bread, all their butter. The butter was made out of beechnuts — highly selected beechnuts. There are still casks and casks of beechnut butter in Europe, buried in the peat, still in good condition. All the bread and cakes in Tuscany and Sardinia and a few other places are still made from chestnuts. Corsican muffins are made of chestnuts, not wheat flour. All the bread was made from the trees, and all the butter was made from the trees. There are your basics.

In your American southwest, the pinion pine nut is a staple Indian food. In one day a family of six can gather thirty bushels of pine nuts, and that’s a year’s supply. In South America, six trees support a family of Indians. Those great supports are a source of staple food. One white oak, in its year, will provide staple food for about six families. A good old American chestnut — how many pounds did we get off one of those trees? At least four or five hundred pounds. There’s a couple of families’ food for a year, with no hacking and digging and sowing and reaping and threshing. Just dash out in autumn, gather the nuts and stack them away. […]

When the forests were managed for their yield and their food equivalence, they were highly managed. Now there are only a few remnants of this in the world, in Portugal, and southern France. In Portugal, you can still find highly selected, highly managed oak trees, often grafted, and olives. The pigs and the goats and the people live together in a very simple little 4,000 yard area in which nobody is racking around with plows. In that economic situation, there is no need for an industrial revolution.

A few of these tree ecologies still remain up on steep mountain slopes, where it has been difficult to get up there to cut the trees down for boat building and industrial uses. The whole of Europe, Poland, and the northern areas once were managed for a tree crop, and the forest supplied all the needs of the people.”

- from Bill Mollison’s design course, ‘Forests in Permaculture’.

Mainstream American (and Canadian) archaeology and anthropology has tended to view native farming systems centered around maize, beans, and squash through the lens of Western farming, which separates cultivated species from their surrounding ecosystems, maintaining annual plants indefinitely through repeated disturbance. Western agricultural practices make it easy to see differences between the domesticated and the wild, and from that perspective it becomes difficult to conceive of a seamless integration of cultivated spaces within the broader ecology. There are few examples of this kind of farming among European settler populations. And we tend to project our own experiences onto those of the past and onto other cultures.

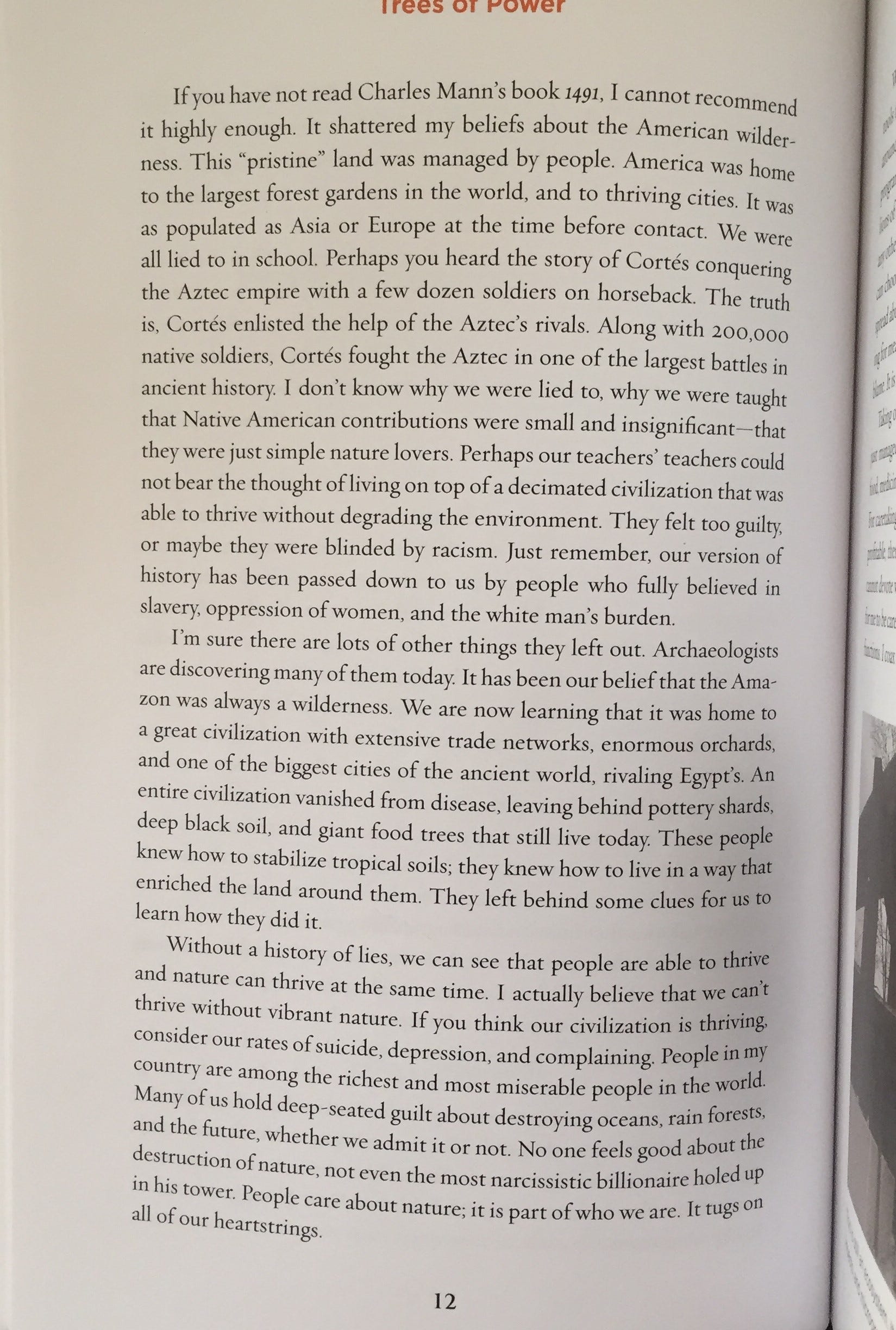

For more insights on how our government education system, text books and modern day western science are woefully lacking, as they are missing a critically important piece of the puzzle when it comes to describing the nature of ancient indigenous food systems of Turtle Island, here is an expert from Akiva Silver’s book (Trees of Power: Ten Essential Arboreal Allies)

Native peoples, however, do not make such rigid distinctions as between the domestic and the wild. This difference of attitude goes to the heart of what sets Native American and European agriculture apart. Not maintaining a distinction between the cultivated and the wild, it becomes difficult to maintain rigid property boundaries. Whereas European agriculture was settled into fixed fields – a constraint wrought by private property enclosure – Native American agricultural fields were “free ranging” and communally owned. Always changing, shifting, fluid, and mobile. Their’s was a shifting cultivation (or “swiddening”). In practice it was worlds apart from the European agriculture.

If one visits Mesoamerica where the Lakandon and Yucatec Maya still practice their traditional milpa, they would realize how the maize-beans-squash complex represents only the early stages of ecological succession within a system of shifting cultivation incorporating hundreds of species from annual weedy plants all the way up to old growth forest trees. The maize-beans-squash crop complex has dispersed all across North America from Mesoamerica, and is known as the Three Sisters all throughout, from Mexico to Canada. The naming of the Three Sisters rests in story, and story provides context.

The milpa, a shifting cultivation system integrating agroforestry, is agriculture as conservation. The milpa is but one member of a family of indigenous cyclical cultivation systems found throughout the forested world. There’s the Tembawang system of the Dayak people of Kalimantan, Indonesia; the Huuhta & Kaski methods of the Forest Finns of Finland and Russia; the Landnam of the Scandinavian Norse; the Jhum cycle of northeastern India and Bangladesh; the Yakihata system of Japan. These integrative, indigenous systems born of deep ecological knowledge share in many features, like an impulse towards reforestation and ecological regeneration — they are the original restoration agriculture.

Trees are homes to a plethora of wildlife. They don’t need to be ripped out of the ground every year. Once they grow a little older, they become resilient defiant beings that don’t need to be coddled with irrigation, fertilizer, or weeding. The simple act of planting a couple of Apple trees could then transform overtime into hundreds of thousands of apples that could feed your family, birds, the soil, and contain seeds that have the potential to create new unique apple trees. The story of the landscape could change indefinitely.

Cultures all over the world of the past and present emanated forest gardening principles in their lives. This included Native Americans, the Chagga people who resided on Mount Kilimanjaro, the Maninjau people in Sumatra, people of the Maya Forest , the Baka people of the Central African rain forest, people of Portugal, and countless others. They all embodied methodology of forest gardening for meeting their most important necessities of life.

The connection of forests as food and the indigenous people of North America became very apparent when I came across a book by Kat Anderson called Tending the Wild. It’s an incredible book about the relationship indigenous peoples of California had with Nature, and it challenged what I had always been taught in school about the history of many Native American tribes. It is often regarded in anthropological documents and history that indigenous people were living a passive hunter gatherer life style and that they did not include agriculture in anyway.

As I discovered more through a range of books (and as I have evidenced above) I learned that this is simply not true. Indigenous people were deeply engaged with the land, planting seeds, pruning trees, initiating controlled burns, and harvesting in ways that gave back to the plants that they gathered from. They were saving seeds from plant beings that exhibited positive traits and planting them out. They drastically changed, diversified, and enhanced the landscape around them. They often stayed in one particular area for their entire lives.

Beyond the scope of hunter gatherers, they were/are also horticulturalists and intensive managers of the forest landscape around them. This way of partnering with forests are not only roots in their way of life. They are the whole tree, and the entire forest. Could it be that forest gardening is actually a much more sound way of creating abundant food bearing landscapes that were rich in healthful ecology?

Welcome to the anthropogenic forest. Overall it is an integrated and beautiful system, and still here centuries later. Cultural landscapes like these are the result of traditional ecological knowledge practiced for generations in place. Cultural forests may be difficult to recognize without the proper context. Indigenous people knew how to build robust, anti-fragile subsistence economies that seemlessly integrated with the broader ecology, and the continuing existence of these forests is testimony to their resiliency. Like the Haudenosaunee who have maintained their democracy for a thousand years into the present, their nut groves are still here, too.

These remnant food forests reveal a host of new questions leading us to deeper understanding and offer us wisdom as we plan how we will cultivate food for our communities going forward.

Forests and farms are exclusively separate in the present western world. Modern agriculture involves rows and rows of open fields, chemical inputs and machinery. Forests are viewed upon as primarily a source of timber or are largely protected as conservation land. What most people fail to realize when looking at our current food systems is that agriculture as we know it is a relatively recent way of interacting with the Earth. And often a very destructive one. For time immemorial, people lived and sustained themselves in rich ways within forest garden systems. This took place in nearly every part of the world, and still do in many parts today.

The question of how can we feed the world without destroying the Earth presses deeper into our current reality. An even more important question to ask is how can we feed our communities in a way that makes the Earth even healthier than before our interaction?

The more I learn to work with this tree the more clearly I come to realize that in climates and bioregions analogous to ours here in Southern Ontario, Shagbark Hickory (and his companion trees) offer one important part of an answer to the question above.

In the spirit of giving back to the living Earth, giving to the 7th generation down the line and beginning to regenerate the food forests of southern Ontario, I have donated several tree seedlings (which I grew from seed) to a group interested in regenerating the forest here. I was honored to be invited to help plant some of those seedlings as part of a Community Food Forest project recently.

We planted Echinacea, Pawpaw and Malus Sieversii seedlings, along with the first Shagbark Hickory seedling to be planted on a property designated for ecological regeneration, traditional food sovereignty initiatives and a community food forest.

Of all the trees in Albion and Ireland the Oak is considered king. Famed for its endurance and longevity, even today it is synonymous with strength and steadfastness in the popular mind. John Evelyn in his Sylva, Or a Discourse of Forest-Trees, calls it the ‘pride and glory of the forest’, and in The Fairy-Faith in Celtic Countries, Evans-Wenze proclaims that ‘the oak is pre-eminently the holy tree of Europe’.

For a glimpse into how my Gaelic ancestors regarded the Monarch of the Forest and King of the Woods, (aka the mighty Oak) here are some select pages from To Speak for the Trees by Diana Beresford-Kroeger

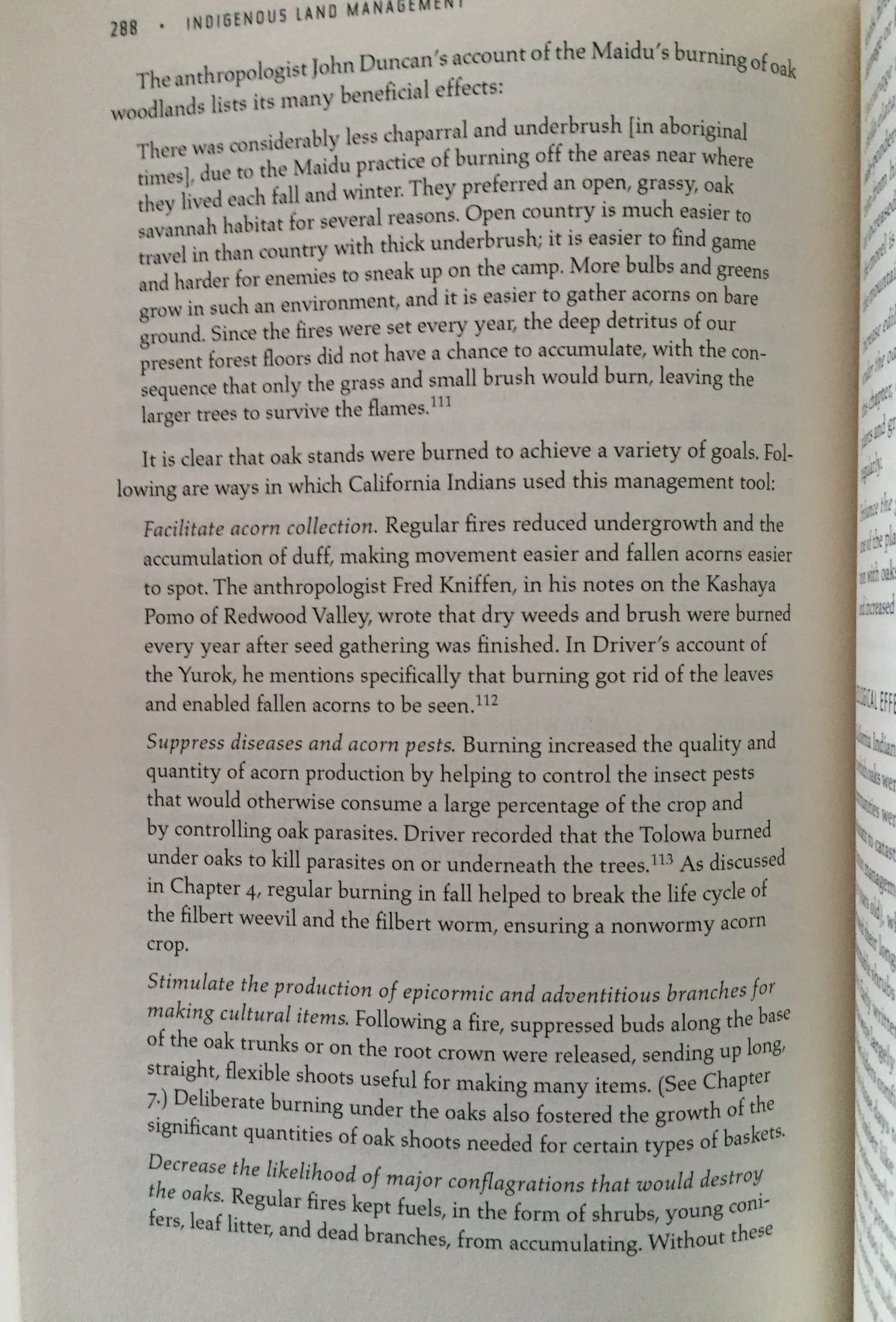

Next I will share a few pages from Tending the Wild by M. Kat Anderson which offers a glimpse into the rich and illustrious balanocultures of pre-colonial California with important info about how they managed their Oak Food Forests with the use of controlled regenerative fire.

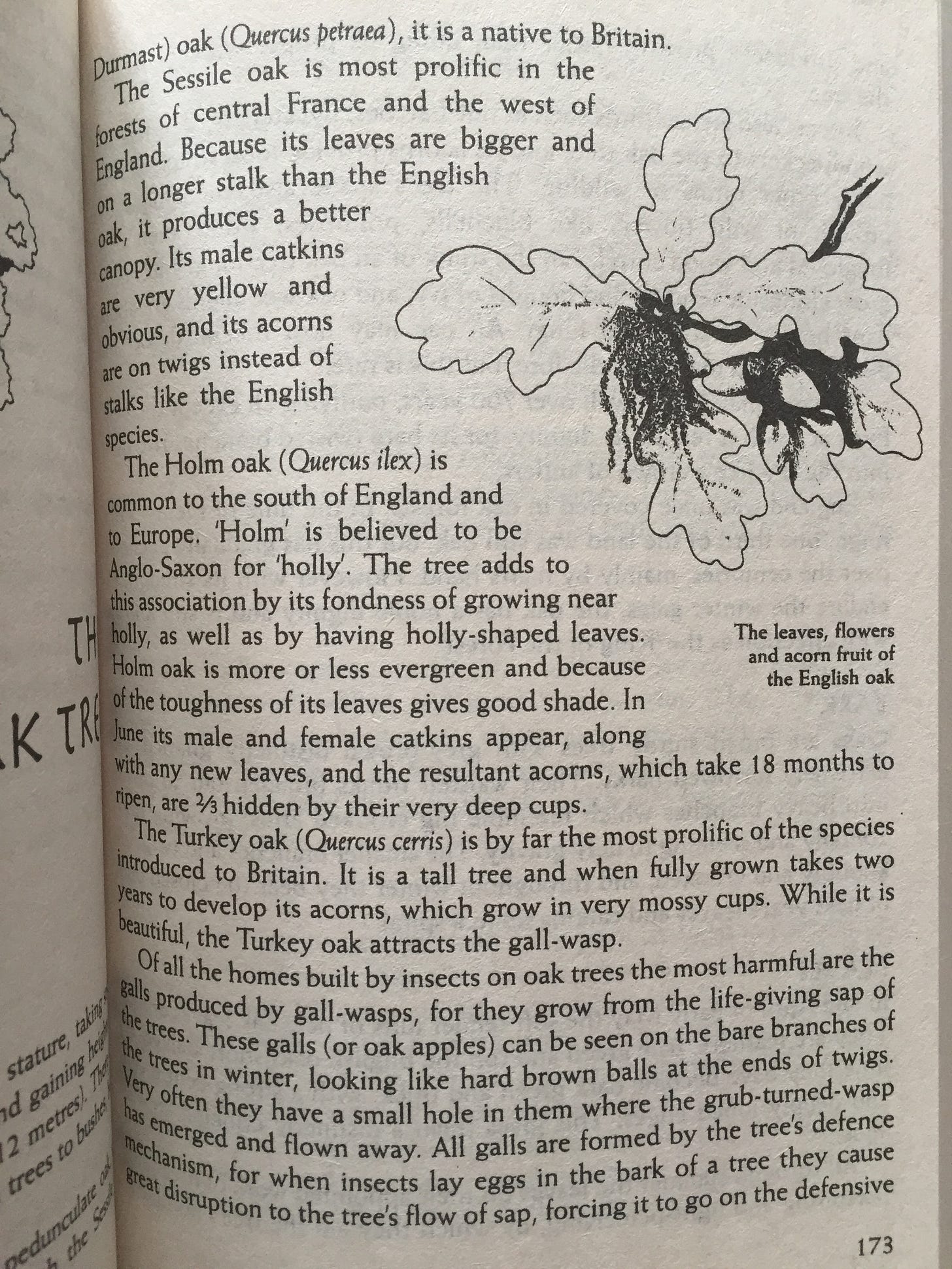

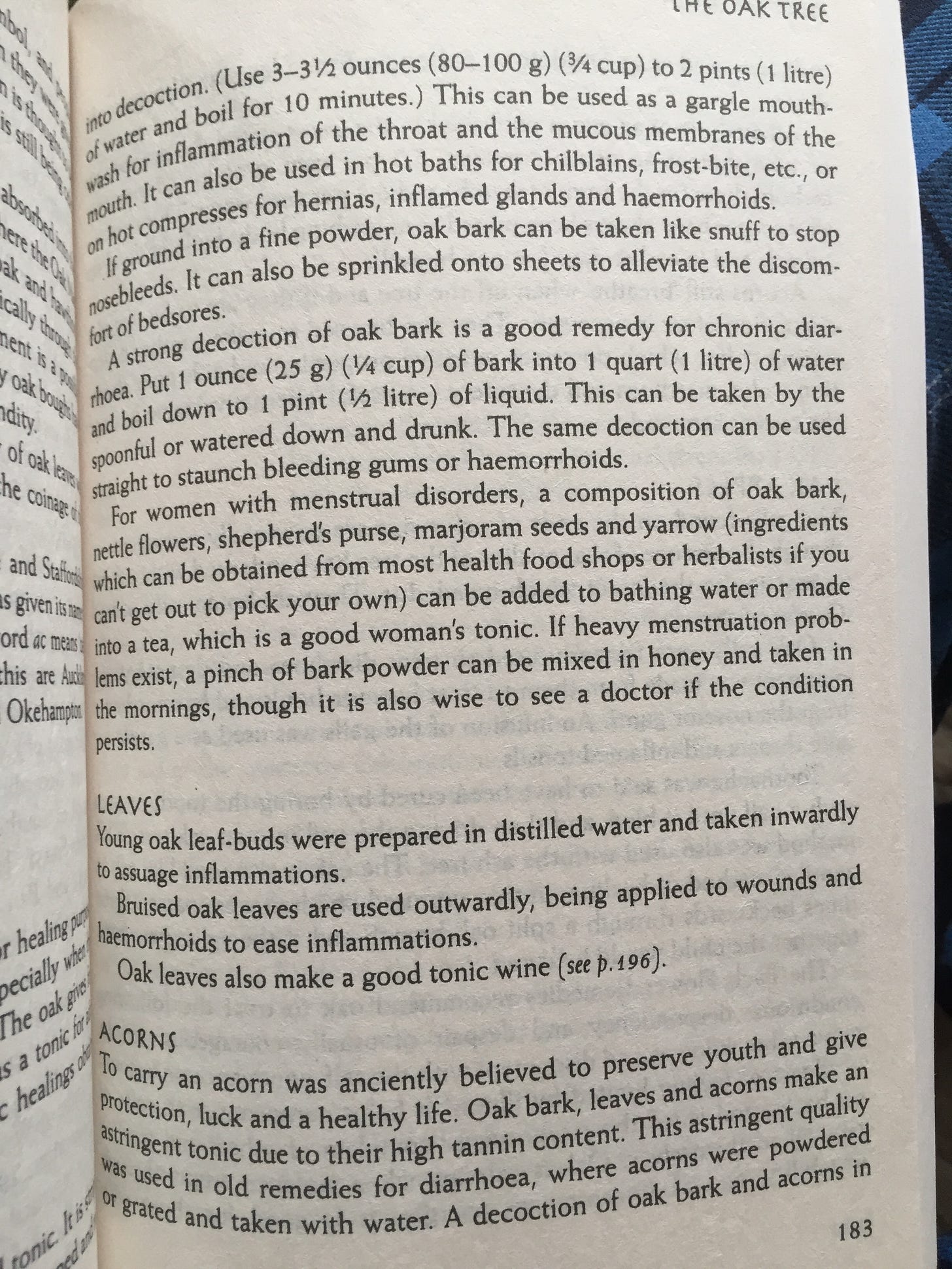

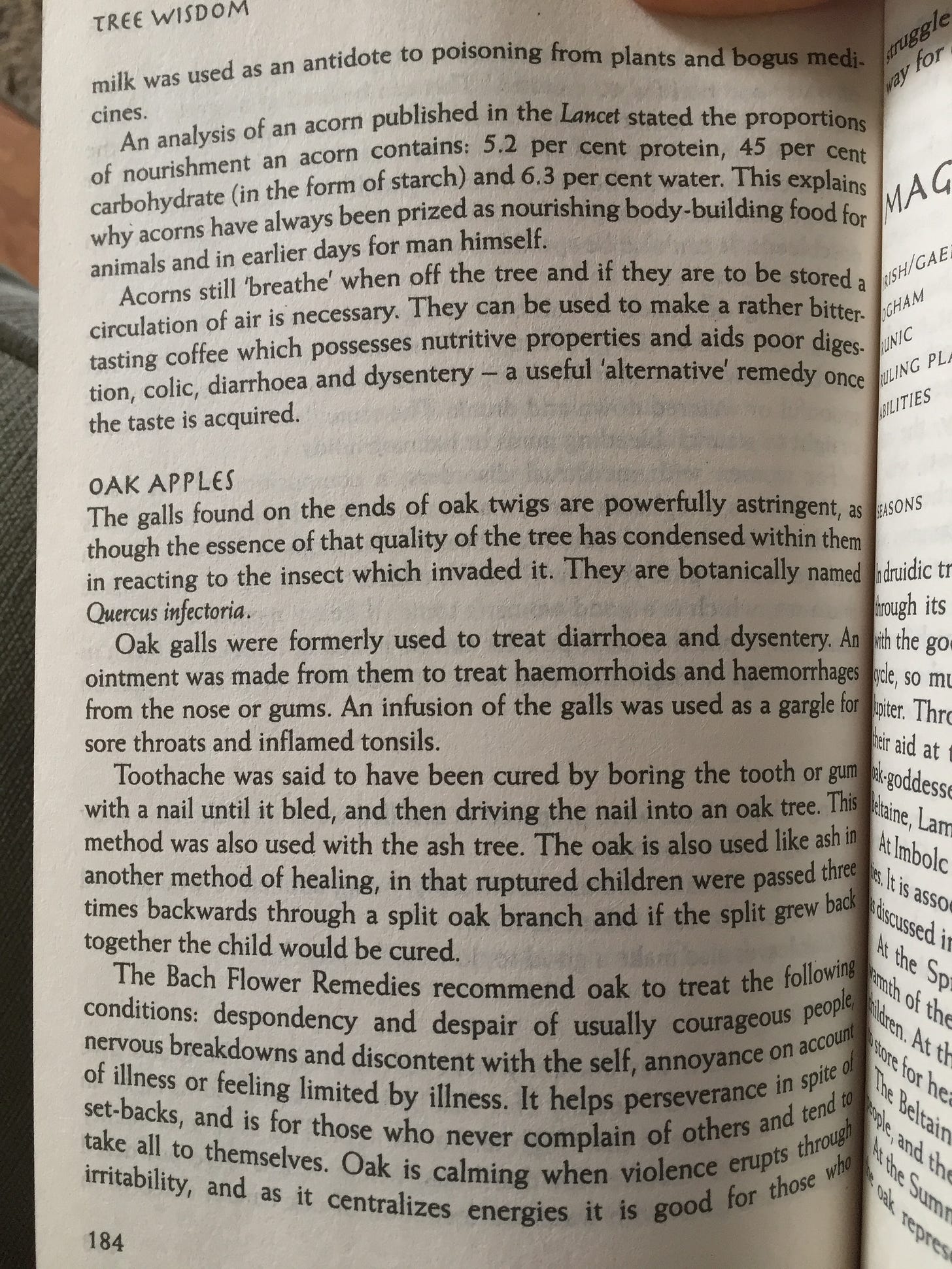

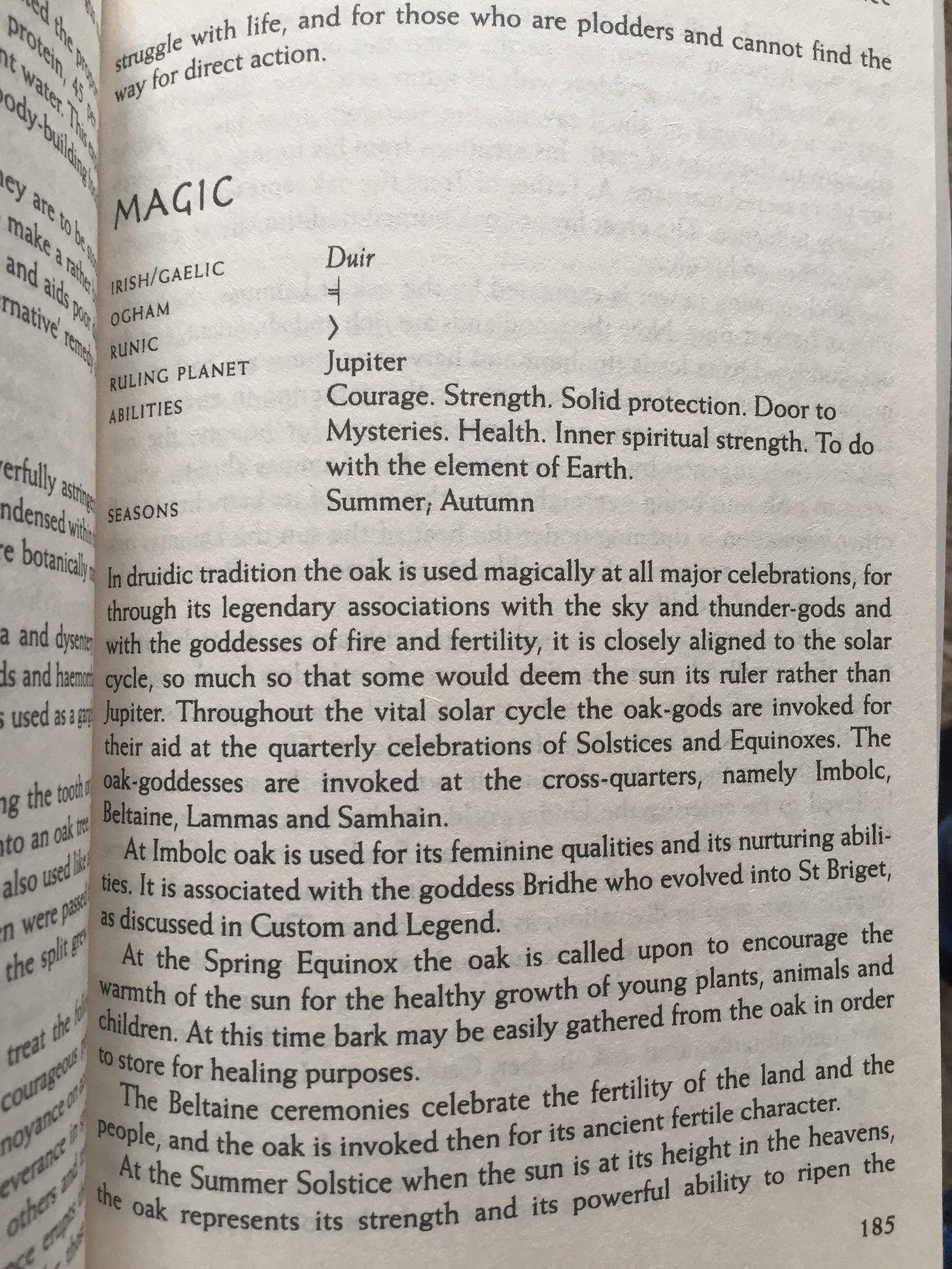

For those that live in Europe (and especially those that live on Albion, aka The British Isles) here are some pages from two more books. First a book called “Tree Wisdom: The definitive guidebook to the myth, folklore and healing power of Trees” by Jacqueline Memory Paterson and “The Living Wisdom of Trees: A Guide to the Natural History, Symbolism and Healing Power of Trees” by Fred Hageneder

Next I will share some pages from A Druid's Herbal of Sacred Tree Medicine by Ellen Evert Hopman :

and last but not least select pages from “The Living Wisdom of Trees: A Guide to the Natural History, Symbolism and Healing Power of Trees” by Fred Hageneder

Acorns as a Traditional Food

Wherever there are Oaks there are acorns, and wherever there are acorns people ate them. There is prehistoric evidence of acorn eating cultures found across the globe. Acorn eating took place from China to Crimea, from the Mediterranean basin to the British Isles.

Ancient agroforestry practices can also be traced to pre-historic Europe incorporating simple forest management techniques such as pruning, burning and intentional planting which created improved foraging areas for wild boar, deer, chamois and even wild aurochs. Spring pruning in the dehesa /montado is the primary method for increasing acorn yields per tree however this would be difficult if not impossible to detect archaeologically. There is evidence of prehistoric fire management of European woodlands by people during the Mesolithic (Mellars, 1976; Mason, 2000). Much of this burning has been perceived as a means of encouraging new growth for browse to support deer and other ungulates. However, as Mason (2000) points out, burning can encourage the proliferation of desirable forest species for human subsistence. In this case, fire may have been used as a tool to manage oaks or other fruit / nut-bearing vegetation. Fire may permit more light to reach the crown thus increasing acorn yield for individual trees (Mason, 2000). Comparisons between Holm oaks in managed stands and natural forests showed that unmanaged trees are generally shorter, found closer together and have smaller canopies (Pulidoet al., 2001). (pp.58-9)

Other extant Balanocultures show similar evidence of burning, pruning and other extensive management to maximise acorn production. In her 2005 book, Tending the Wild, Kat Anderson builds a picture of techniques used by Indigenous peoples in California, some still within living memory. Acorns provided a ‘principle staple’ for the people there, with records of charred shell remains going back at least 10,000 years (p.287). This sounds like fun:

Individuals of many tribes harvested acorns by climbing the trees and cutting the limbs, a process Galen Clark recorded among the Yosemite Miwok: “In order to get the necessary supply [of acorns] early in the season, before ripe enough to fall, the ends of the branches of the oak trees were pruned off to get the acorns, thus keeping the branches well cut back and not subject to being broken down by heavy snows in the winter and the trees badly disfigured, as is the case since the practice has been stopped.” The Mono elder Lydia Beecher remembered the former pruning of oaks: “My grandpa Jack Littlefield would climb black oak trees and cut the branches off—just the tips so that many more acorns would grow the next year” (p.139)

As with practically all the other plant communities they ‘tended’, the indigenous peoples used fire to manage Oak trees. This served various purposes such as: helping to facilitate gathering, suppressing pests and diseases, encouraging the growth of long, flexible new shoots (useful for basketry etc.), building soil with biochar, keeping forest debris levels down so fires wouldn’t rage out of control, and fostering the growth of edible grasses, herbs and mushrooms between the trees (pp.288-9). As ‘Klamath River Jack from Del Norte County’ put it:

Fire burn up old acorn that fall on ground. Old acorn on ground have lots of worm; no burn old acorn, no burn old bark, old leaves, bugs and worms come more every year…. Indian burn every year just same, so keep all ground clean, no bark, no dead leaf, no old wood on ground, no old wood on brush, so no bug can stay to eat leaf and no worm can stay to eat berry and acorn. Not much on ground to make hot fire so never hurt big trees, where fire burn. (p.146)

As late as 1991 ‘Rosalie Bethel, Nork Fork Mono’ could still recall her elder’s stories from the 1800s:

Burning was in the fall of the year when the plants were all dried up when it was going to rain. They’d burn areas when they could see it’s in need. If the brush was too high and too brushy it gets out of control. If the shrubs got two to four feet in height it would be time to burn. They’d burn every two years. Both men and women would set the fires. The flames wouldn’t get very high. It wouldn’t burn the trees, only the shrubs. (p.177)

The resulting ‘Oak Savanna‘ habitats which were often compared to parkland by early European observers (p.175):

Pollen and microcharcoal sequences from Mesolithic Britain’ offers hints that acorns have been important to peoples all over for tens of thousands of years