Hazelnut - she is the evoker of wisdom, vanguard regenerator of fire or ice scoured lands and beholder of the watery depths

This is the 30th installment of the Stacking Functions in the Garden, Food Forest and Medicine Cabinet : The Regenerative Way From Seed To Apothecary series.

This post serves as the 30th post which is part of the above mentioned (Stacking Functions in the Garden, Food Forest and Medicine Cabinet : The Regenerative Way From Seed To Apothecary series).

These rooted beings were known as Colltainn or Coll to my Gaelic ancestors. In the Gaelic Ogham script, the hazel tree is represented by the letter "Coll", which is the ninth letter of the alphabet. The Ogham alphabet is often referred to as the "Celtic Tree Alphabet" because each letter is associated with a tree, and Coll is specifically linked to the hazel. The hazel is known for its association with wisdom, knowledge, and creativity in Celtic tradition.

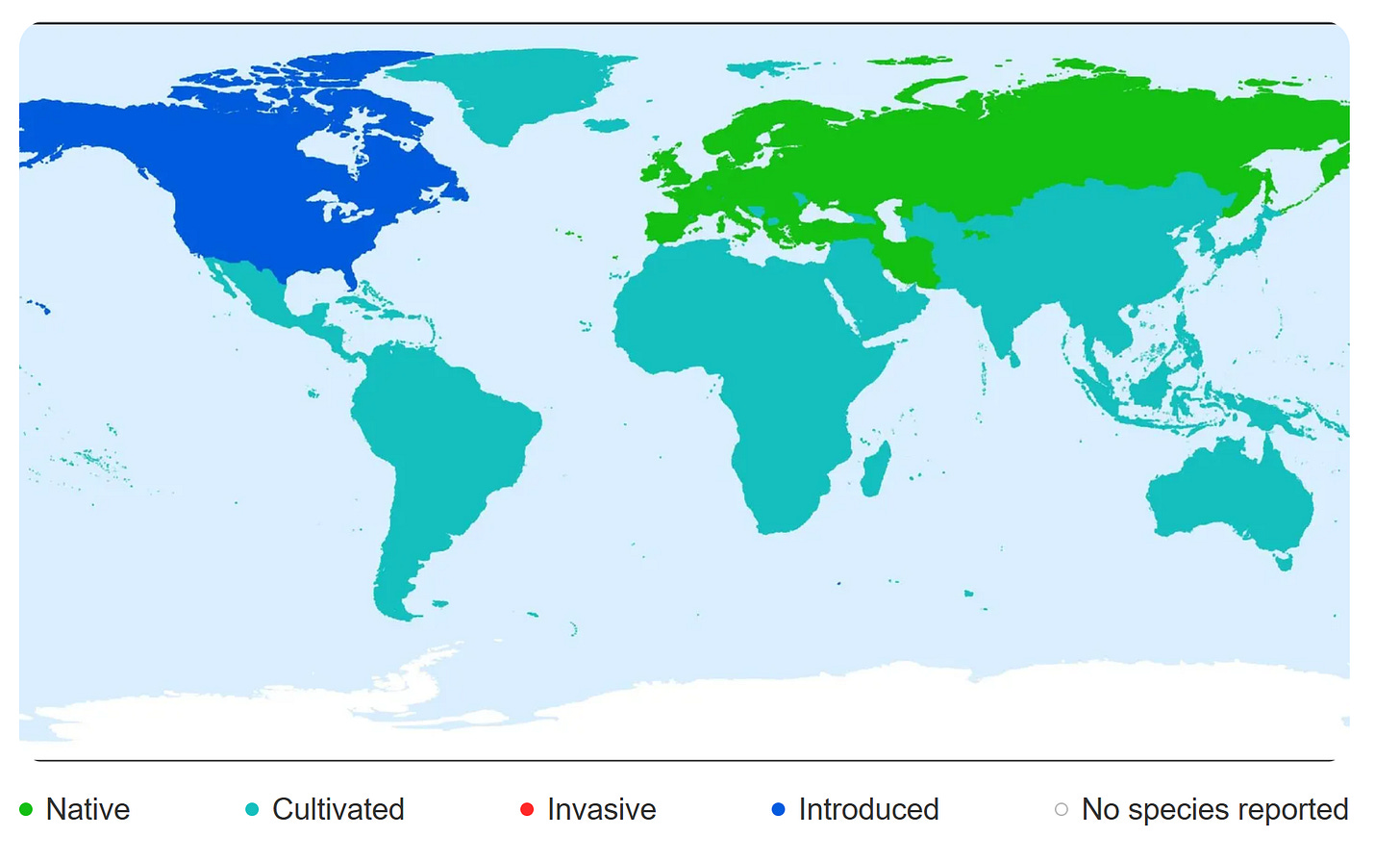

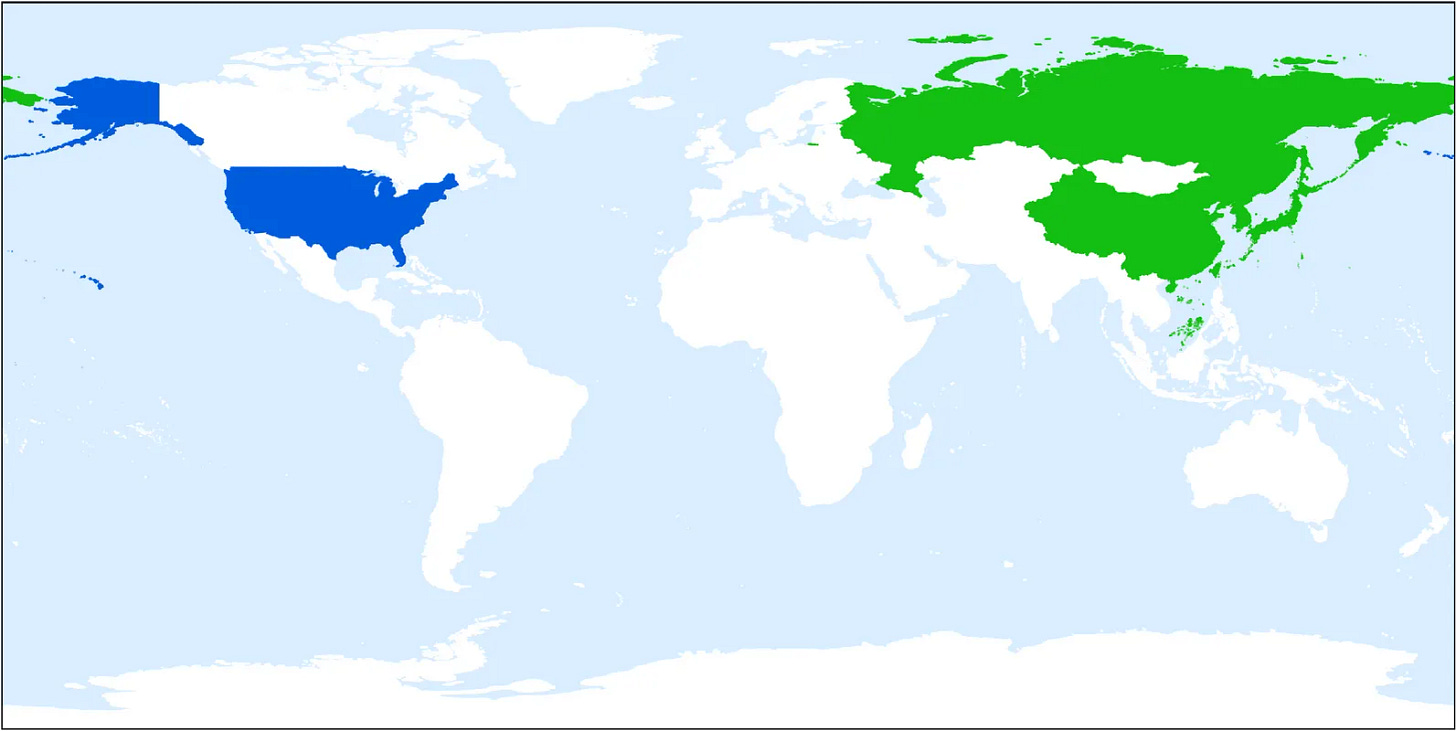

Hazels are so resilient that they have been cultivated by ancient cultures from lands that are now called “Norway”, to “Finland” to “Russia”, “China”, “Alaska” “Newfoundland” and “Labrador” making Hazel (especially beaked hazel) a powerful ally for the northern food forest designer. In some areas of northern Europe and what is now called “Canada” various types of Hazel were cultivated along side other resilient and medicinal crops such as Golden Root (Rhodiola Rosea and Rhodiola integrifolia).

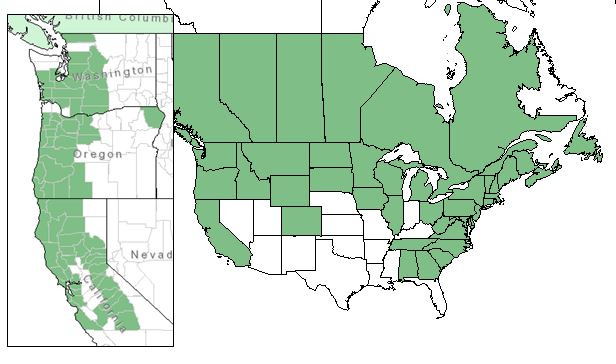

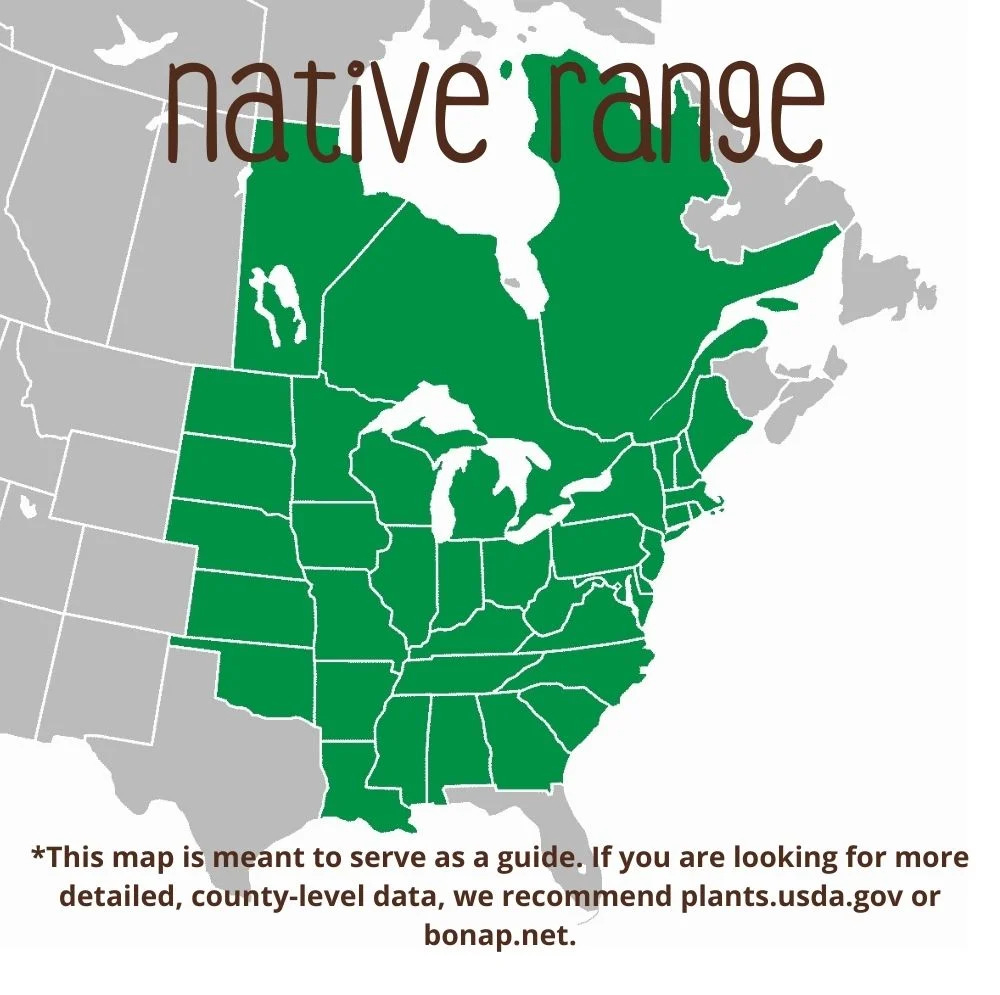

Here on Turtle Island a diverse array of cultures allied with the native Hazel to create food forests that persisted for centuries to millennia. Some of these food forests still produce today (despite the fact that their architects and stewards were forcibly removed in the name of “progress” and “civilization” decades ago). These are trees that can be powerful allies for our human family, enabling multi-generational abundance of both food and biodiversity to be left behind for the 7th generation that comes after we are gone.

They are absurdly tough and long-lived. I recently read that if you cut a mature plant flat to the ground, it will grow right back up the next year. This is because the American half of its ancestry is adapted to the wildfire biome of the American savannah, where wildfire used to be common.1 They tolerate both drought and flood.2 But it gets better. Hazel breeder Phil Rutter has reported that they also survive tornadoes, hailstorms, and downbursts.3 He mentions that it takes something like a backhoe to kill a mature hazel.4

Hazel is a multi-purpose champion of a plant that is super easy to grow, produces delicious nuts, pliable wood (which can be grown regeneratively via coppicing) that can be crafted into a variety of products, provides early fodder for bees and an encouraging spectacle when flowering during the mid-winter.

In a similar way to what I described in my articles on Oak trees, Birch trees as well as Pine trees, this ancient tree family is found in almost the entire Northern Hemisphere, meaning that the Hazel is one of those tethers to the ancient Indigenous history of all people who have ancestors that called the northern hemisphere home.

Thus, these resilient, wise and nourishing rooted elder beings of the Hazel family offer a sacred reminder of a time before arbitrary lines were drawn in the sand by statists for greed and ego back to an era when many of our ancient ancestors knew the trees intimately and had a reciprocal relationship with them. Long before people were swearing allegiance to kings, queens and flags they were swearing allegiance to the living Earth and recognizing our ancient kin (such as these beings we know as Hazel trees/shrubs) and the many gifts they shared with us.

If your ancestors hail from the northern hemisphere Hazel trees/shrubs offer you a sort of universal language to perceive the common ground you share with the ancestors of those now residing in nation states far and wide. This rooted being offers you a glimpse into your own indigeneity and your ancestors relationship to place. Yes, all of us have an indigenous past connected to our blood and our soul. For some of us, that indigeneity is buried under multiple millennia of bloodshed, oppression, re-writing of history and statist propaganda. Though it may be buried deep and many may have sought to erase that part of your heritage from the stories of modern cultures, this part of you exists nevertheless. This is part of your ancient heritage, when your ancestors lived close to the land and the forest and recognized more than human beings as deserving of our respect as conscious beings.

After you read the article below and learn about all the beauty, blessings and the many gifts offered to us by the Hazels of the world, I invite you to look upon her with gratitude and reverence for all that she shares with the world. In doing so, you will be choosing to see the world through the eyes of your ancient ancestors.

Through seeing trees like Hazel as those whose blood flows in your veins now did millennia ago you begin to unlearn the lies, self important delusions and separation mentality that is inherent in modern civilization. In that act to see the Hazel with the understanding and reverence of those who came before you and walked the earth with respect eons ago, you are building a tangible bridge that connects you to your honoured elders and ancestors and a bridge that also directs you towards a more Regenerative, humble and hopeful future.

Such are the blessings we are given when we learn to see the living earth and our rooted elder kin as the ancients did, as wise teachers, protectors, healers, sources of inspiration, regeneration and renewal.

When we learn to perceive and interact with our rooted kin (such as Hazels) as our ancestors did we shatter the modern illusion of separation that nation states attempt to impose on us and begin to speak a universal language that connects us all as equals.

What more can I say.... a plant so exceptional that people started naming their daughters after it.

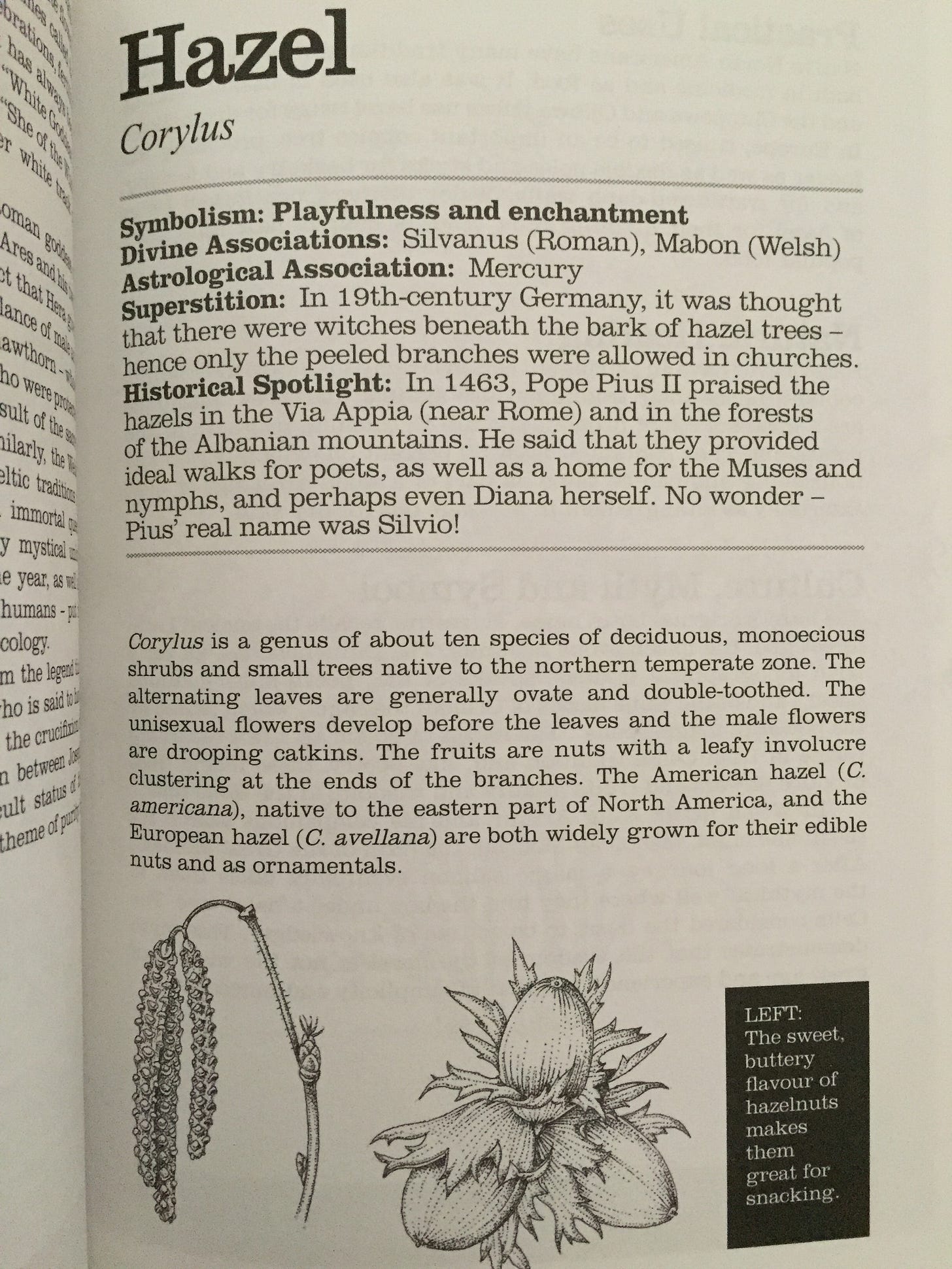

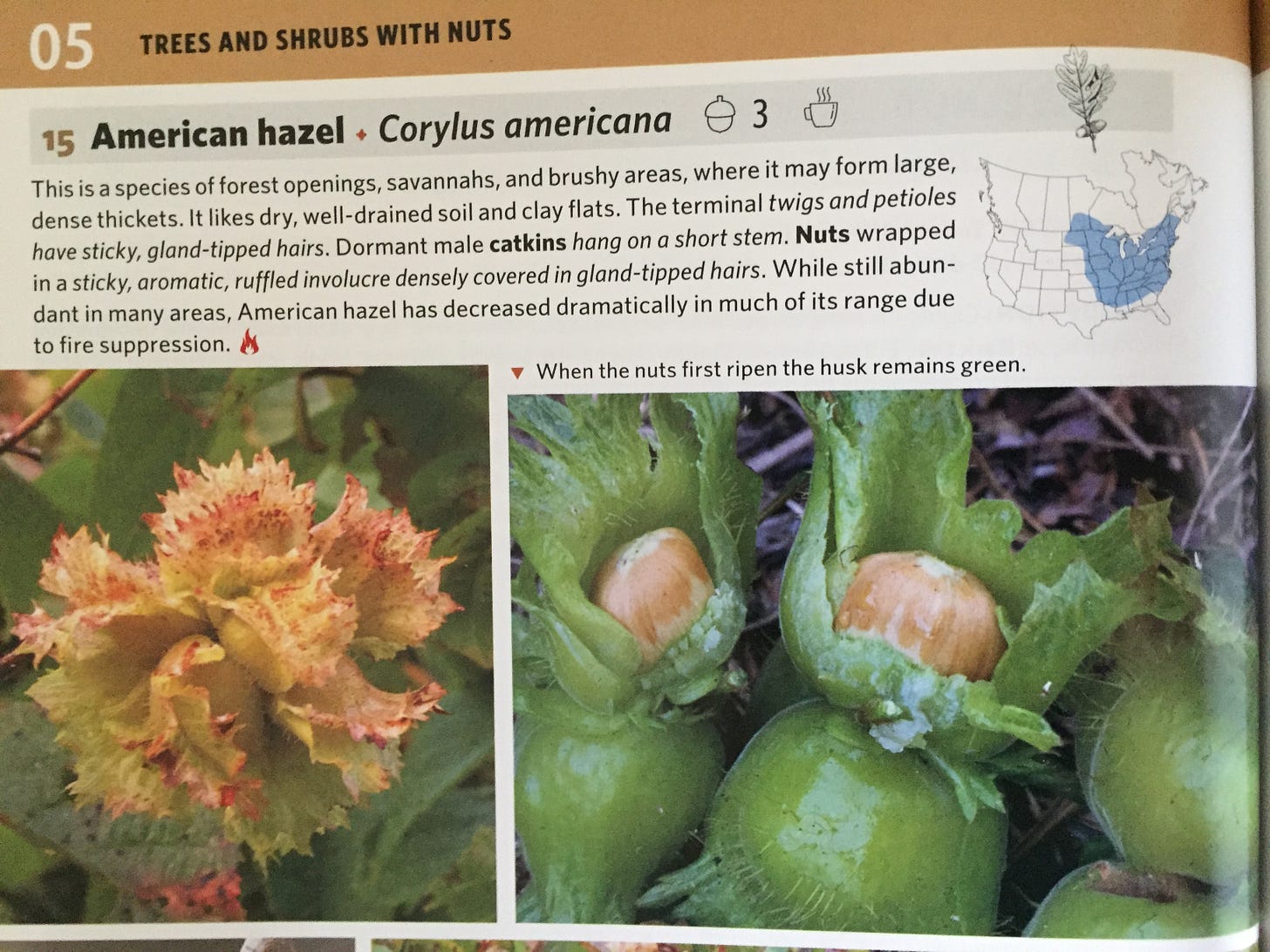

Corylus cornuta, Corylus americana, Corylus avellana, Corylus maxima, Corylus heterophylla

Common Name: Hazelnut, cobnut and filberts

Family: Corylus

Part used for medicine/food: the hazelnut kernel (the nut itself), oil, the leaves and bark

Constituents: healthy fats, protein, fiber, and various vitamins and minerals, including vitamin E, copper, magnesium, thiamine, manganese, procyanidin oligomers, quercetin, catechin, epicatechin, gallic acid

Medicinal actions: The bark, leaves, flowers, catkins and nuts are all considered astringent, wound healing, cardioprotective benefits, Neuroprotective and Neuro-regenerative, blood purifying, Osteoprotective and Osteoregenerative, fever-fighting, Ocular-Protective benefits, and sweat-inducing. Traditionally, hazel has been used to treat conditions like coughs, colds, hemorrhoids, varicose veins, and circulatory problems. Additionally, the nuts are a source of nutrients and have been used to soothe upset stomachs.

Pharmacology: research shows that hazel offers antioxidant, anti-inflammatory, and antimicrobial properties, particularly in hazel leaves and nuts.

Cold Hardiness: 2-9

Native Range:

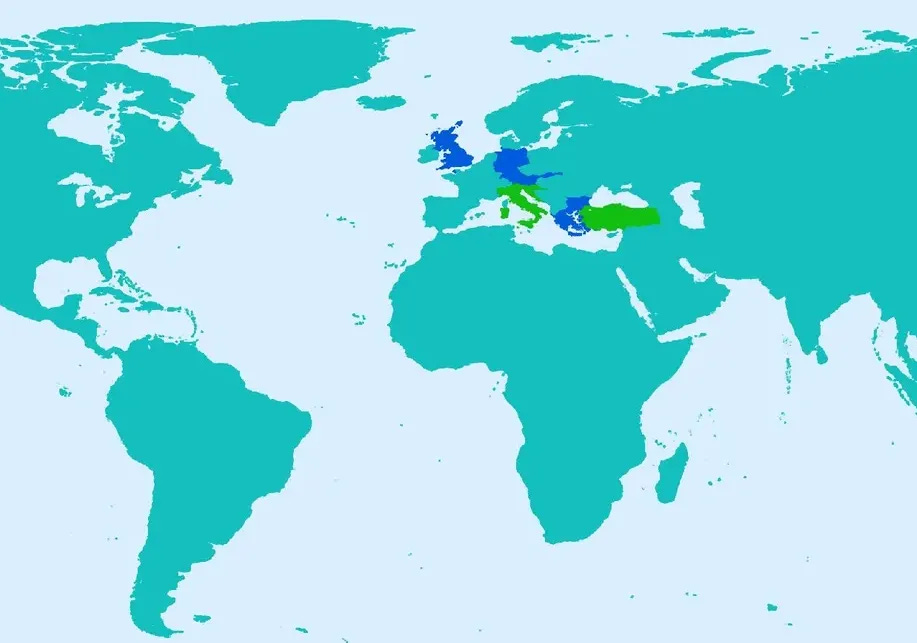

Hazels have an extensive range and can be found throughout the northern hemisphere anywhere there is an appropriate temperate climate. Hazel species grow wild in North America, Europe, the Caucasus, and parts of Asia, including China, Tibet, and Japan.

Hazels will grow in woodlands, meadows, abandoned fields, forest edges, railways, stream valleys, fencerows, pine barrens, and gardens. Hazels will grow in full sun or partial shade. They’re often an understory species but are more common in open woodlands than those with dense canopies.

Hazel is widely distributed throughout much of Europe, from Britain and Scandinavia eastwards to the Ural Mountains in Russia, and as far south as Spain, Italy and Greece. It also occurs in Morocco, Algeria, Turkey, Iran and the Caucasus region.

Within this large range its distribution is uneven and it typically grows as an understorey component of deciduous forest, especially with oaks (Quercus spp.), although it also occurs with conifers.

Growth Forms:

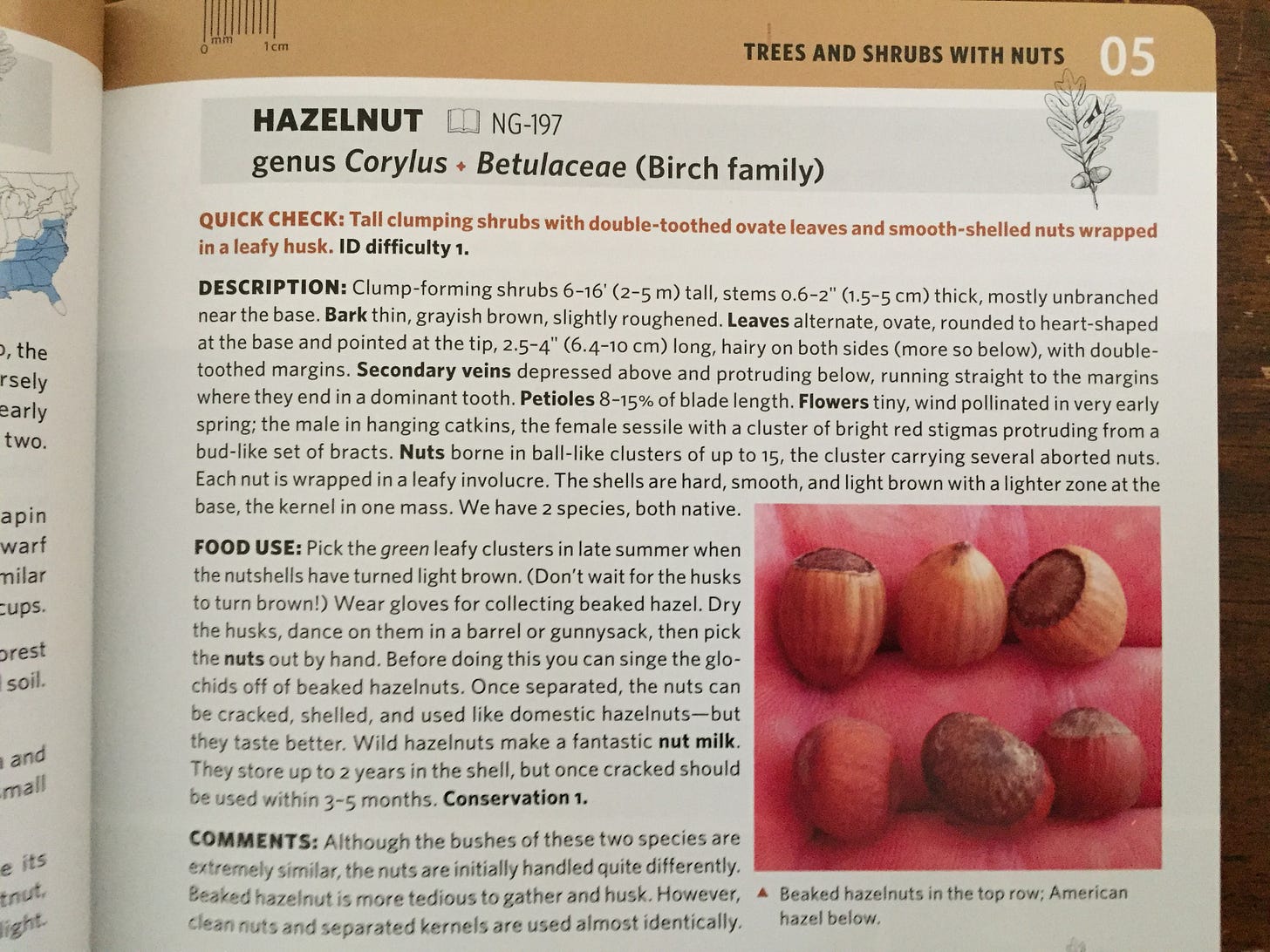

Corylus cornuta

also known as beaked hazelnut, is a multi-stemmed, deciduous shrub with an upright-spreading growth habit. It typically reaches a height of 4-8 meters (13-26 feet) and can have stems 10-25 centimeters (4-10 inches) thick. This shrub is known for its ability to form dense thickets through suckering and rhizomes.

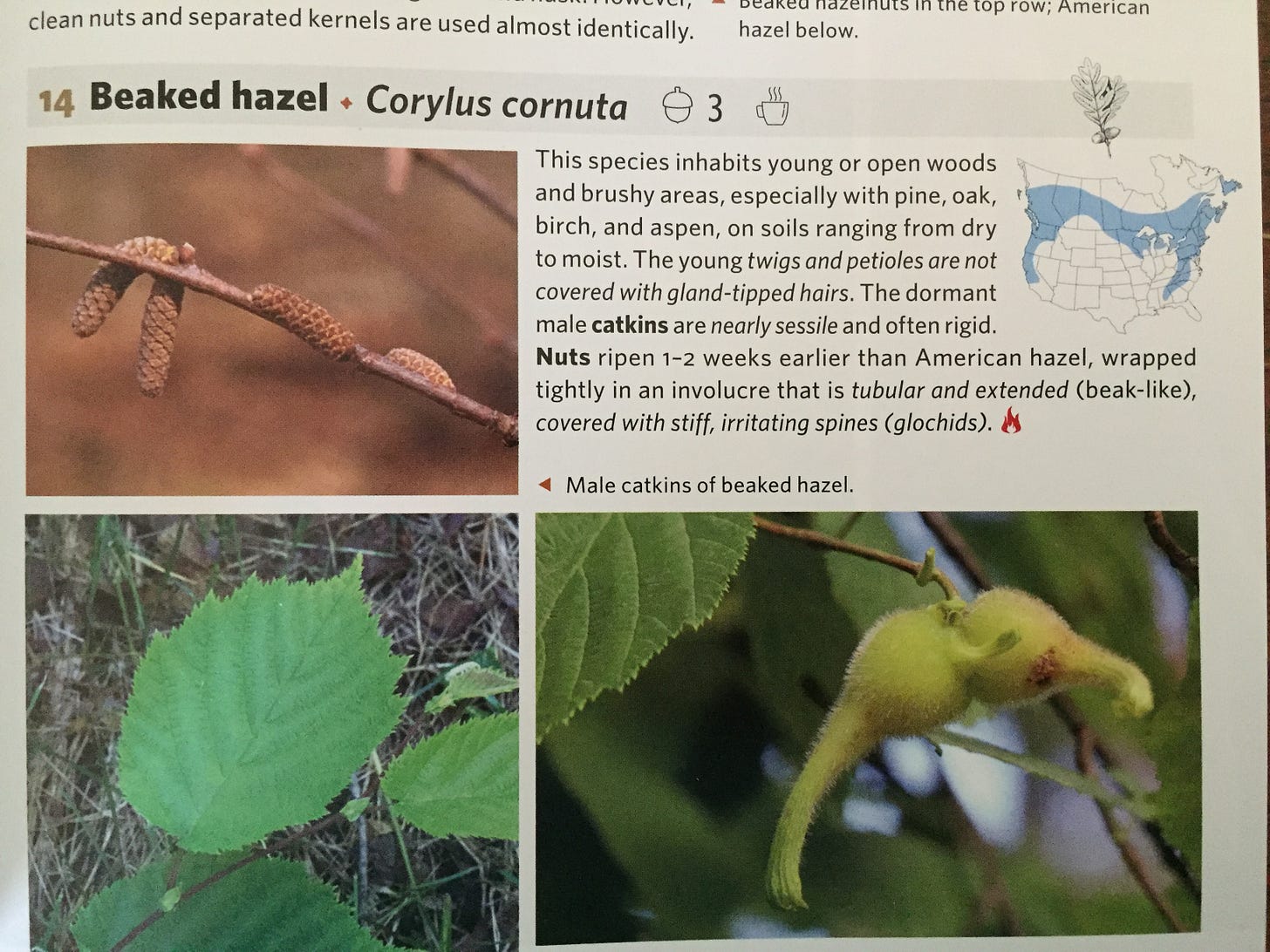

Corylus americana

commonly known as American hazelnut, is a multi-stemmed, deciduous shrub that typically grows to a height of 8-16 feet (2.5-5 meters). It has a rounded, spreading habit, often forming dense thickets due to its rhizomatous (underground stem) growth. Under certain conditions, it can even resemble a small tree.

Corylus avellana

commonly known as the common hazel, typically grows as a stout shrub or a small tree with multiple stems. It can reach heights of 3-8 meters (10-26 feet), but can exceptionally grow up to 15 meters (49 ft). The plant can be pruned to maintain a desired shape, either as a shrub or a small tree.

Corylus maxima

commonly known as the giant filbert or giant hazel, typically grows as a large, suckering, deciduous shrub or small tree. It can reach heights of 12-20 feet (4-6 meters). The growth form is characterized by multiple stems, forming a somewhat rounded or spherical crown. Some cultivars, like 'Purpurea', can be trained into a more tree-like form.

Corylus heterophylla

also known as the Asian hazel or Siberian filbert, typically grows as a deciduous shrub or a small tree, reaching heights of up to 7 meters (23 feet). It's characterized by its spreading habit, sometimes forming thickets. The bark is typically gray and can become rough and fissured with age. It's known for its variable leaf shapes, which can be oblong, ovate, or obovate, and have irregularly serrated edges.

Reproduction:

Hazelnuts are monoecious, meaning they have separate male and female flowers on the same tree. Male and female flowers may bloom at different times.

Hazel have a very early flowering time compared to most nut trees. In some areas, the pollination season starts in January. How many plants pollinate during winter? Not many.

It starts with catkins, a long droopy flower that first appear on hazelnuts in the spring. Catkins are the male parts of the tree that produce and release pollen.

The pollen is spread by the wind to these tiny red flowers, the female parts of the hazelnut tree. Pollen can be spread up to 50-feet, but rarely does it have to travel that far. Every hazelnut tree has both male and female flowers, so all the pollen has to do is reach the tree next to the one it came from. In case you’re wondering, hazelnut trees can’t pollinate themselves. The pollen must come from another tree.

What makes the hazelnut truly different from virtually every other plant is that when the pollen reaches a flower, nothing happens. The pollen, or sperm, goes dormant for months while the flower continues to develop. Sometime in late April or early May, the sperm reawakens and finally fertilizes the tree. A mere six weeks later and the nuts of the tree are fully grown.

Habitat and Ecological Niche:

The American hazelnut (Corylus americana) occupies a broad ecological niche, thriving in diverse habitats across eastern North America. It is a mid-seral species, commonly found in woodlands, forest margins, hedgerows, and roadsides, as well as disturbed areas like clearings and reclaimed mine sites. It prefers rich, moist, well-drained soils but can tolerate a range of conditions, including some shade and drier sites.

Ecological Interactions:

Food Source:

The nuts are a valuable food source for many animals, including squirrels, deer, foxes, various bird species (like grouse, turkey, woodpeckers), and rodents. Thus, for those looking to eat meat and hunt, this is a species that invites your dinner to come to you. The male catkins (flowers) are also eaten by grouse and turkey during the winter.

Habitat Provider:

The shrub's dense branching structure and large leaves offer excellent cover and nesting habitat for wildlife, including songbirds.

Pollination:

American hazelnut is not self-fertile and requires cross-pollination from another plant. Bees are attracted to the abundant pollen produced by the male catkins.

Interactions with Other Plants:

It can be found growing alongside various other plant species, including shagbark hickory, raspberries, sumac, and dogwood.

The ecological niche of beaked hazelnut (Corylus cornuta) is characterized by its adaptability to various habitats, including somewhat-wet to wet forests, alder swamps, and forest edges. It thrives in areas with a mix of sun and shade, tolerating partial shade but also preferring open canopies. The species is relatively shade-tolerant but not intolerant of entirely open, hot, and dry conditions. Beaked hazelnut is also known to be a fire-adapted species, readily resprouting from its root crown after fire disturbance.

Ecological Interactions:

Food Source:

Beaked hazelnut nuts are a significant food source for many wildlife species. Squirrels, chipmunks, and other small mammals consume the nuts, burying some for later use, which can aid in seed dispersal. Birds like grouse, pheasants, and some woodpeckers also eat the nuts. Deer, moose and rabbits love them. Thus, , again, for those looking to eat meat and hunt, this is a species that invites your dinner to come to you. The nutrient-rich catkins and buds are consumed by grouse and other birds.

Shelter and Nesting:

The shrub provides cover and nesting habitat for various birds, including ruffed grouse. The dense thickets formed by beaked hazelnut offer protection for smaller animals.

Browsing:

Moose and beaver browse on the stems of beaked hazelnut, particularly in winter. Deer also browse on the foliage, especially during the winter months.

Seed Dispersal:

While squirrels and chipmunks primarily distribute nuts locally, jays like the blue jay and Steller's jay can disperse them over longer distances. The nuts buried by rodents have a good chance of germinating.

Influence on Plant Communities:

Beaked hazelnut can form dense thickets, potentially outcompeting other plant species (so potentially great as a barrier planting on the edge of your food forest). Its ability to resprout after fire can also influence the recovery of plant communities (and means this tree have evolved along side indigenous regenerative fire management on Turtle Island for millennia).

Human Interactions:

Native Americans have long used beaked hazelnut for food, with the nuts being consumed fresh or stored for later use. Twisted twigs were used for tying, and straight stems for arrows or weaving.

Common hazel (Corylus avellana) thrives in a variety of habitats, including woodlands, hedgerows, and forest edges. It prefers well-drained, moderately fertile soils and can tolerate a range of conditions, including full sun to part shade.

Ecological Role:

Food Source: Hazel provides food for various wildlife, including squirrels, deer, turkey, and birds like woodpeckers, pheasants, and jays, who eat the nuts. The catkins are a food source for ruffed grouse in the winter.

Habitat: It offers shelter for ground-nesting birds and other animals.

Soil Stabilization: Being a pioneer species, hazel can help stabilize soil, particularly in disturbed areas.

Support for Other Species: Hazel leaves are food for the caterpillars of numerous moths, and coppiced hazel provides habitat for butterflies and other insects.

At least 21 species of fungus have a mutualistic relationship with hazel.

Hazel is an important understorey tree in the Caledonian Forest, providing nuts for squirrels and other rodents, and it also supports a rare lichen community.

orylus avellana is a common understorey species in naturally regenerated mixed-hardwood stands, a frequent component of traditional field-boundary hedgerows, and has been a key species in European woodlands throughout the last 10,000 years (Hegi, 1981).

Relict forests of uncoppiced Atlantic Hazelwood in western Scotland and Ireland, as well as submontane stands on steep slopes in the Peak District and Lake District of England, may be under-represented in official community designations to date, particularly given their apparent ancient history and the diversity of lichens supported by the regenerating bark of C. avellana (Coppins & Coppins, 2003). These relict temperate forests warrant attention for their abundant diversity of cryptogamic plants; this is a globally uncommon habitat of minimal annual temperature variation together with high humidity and annual precipitation. The stools of C. avellana produce a cycle of bark surface continuity for specialized woodland lichens, for example Graphis alboscripta Coppins and P. James (White Script Lichen) known only from ancient Hazelwood stands in western Scotland.

Many fungal species grow in association with C. avellana in Britain and Ireland although relatively few are specific to this host. It has been suggested (Holden, in Coppins & Coppins, 2010) that soils characteristic of Hazel woodland (characterized by efficient detritivores in the soil, including earthworms) support both fewer fungal species and lower fruit body production than those associated with acidic conditions such as coniferous woodlands or moorlands. Where mature C. avellana grows in the Atlantic seaboard it is an important host for Hypocreopsis rhododendri Thaxt. (Hazel Gloves), a fungal species designated on the IUCN red list as Near threatened (Evans et al., 2006).

Corylus avellana is a member of a wide range of woodland and scrub communities in the National Vegetation Classification system (NVC; Rodwell, 1991), listed in Table 1, in which it is particularly prominent in Ash woodlands W8 (lowland) and W9 (upland). These vegetation types are currently in a state of ecological flux while the introduced fungus Hymenoscyphus fraxineus Baral et al. (Chalara Ash Dieback) sweeps through Ash trees in the region. In the north and west, these woodlands with C. avellana provide a food resource for Red Squirrel (Sciurus vulgaris L.) and Pine Marten (Martes martes L.) and the structural canopy over the river basin for Otter (Lutra lutra L.), Water Vole (Arvicola amphibius L.) and spawning salmonids (e.g. Atlantic Salmon, Salmo salar L. and Sea Trout, Salmo trutta L.). In the first few years following Chalara Ash Dieback and/or anthropogenic removal there may be increased niche availability for the pioneer C. avellana, but it seems reasonable to assume that there would be replacement in the following decades, assuming propagule arrival of larger, longer-lived tree species.

Flowering and Pollination:

Parts of Florets (female) :

Stigma. Portion of the style that is receptive to pollen germination. The stigmatic surface of hazelnut female flowers is red and covers the entire surface of the style.

Style. Elongated stalk that connects the stigma to the ovary.

Ovary. Basal portion of the female flower that bears the ovules. The ovary consists of a wall of tissue (eventually the nut shell) and two ovules.

Ovule. Structure within the ovary that bears the egg.

Egg. Female cell that (after fertilization) develops into the embryo.

Parts of Catkins (male) :

Anther. Pollen-bearing portion of the stamen.

Catkin. Pollen-producing organ.

Pollen. Grains bearing sperm formed in anthers on catkins.

Pollen germination. Growth of a pollen tube out of the pollen grain. This occurs when pollen is placed under suitable conditions, such as on the stigmatic surface of compatible flowers.

Health Benefits of Hazel:

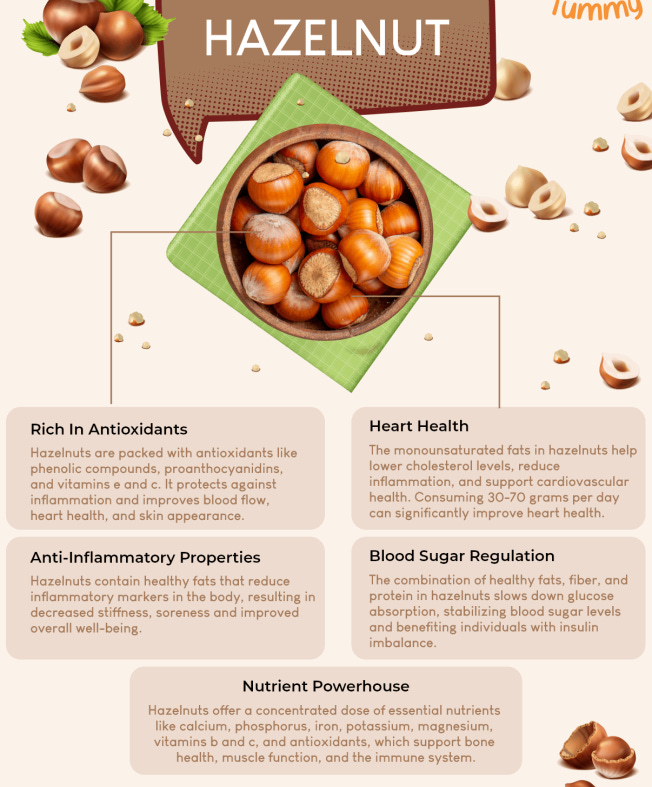

Hazelnuts are incredibly nutritious. Hazelnuts contain 15% protein and are rich (60%) in fatty acids, vitamins and minerals, such as iron, calcium, potassium, selenium and magnesium. They are high in antioxidants, fiber, and healthy fats like omega-6 and omega-9. They also have good folate, vitamin B6, phosphorus, and zinc levels.

Incorporating them into your diet may have heart health benefits. In 2012, researchers had participants consume a diet where 18 to 20% of their daily calorie intake came from hazelnuts. The participants saw reduced cholesterol, triglycerides, and bad LDL cholesterol levels.

Researchers also found that hazelnuts have particularly high levels of antioxidants called proanthocyanidins compared to other nuts like pecans and pistachios. These antioxidants are believed to protect against oxidative stress and may help prevent or treat cancer.

Today, we focus on the nuts, but through the ages, the leaves, bark, flowers, and catkins were all part of medicinal remedies. Herbalists have used the catkins, bark, and leaves to make teas, the catkin tea for colds and flu, the bark tea for fever, and the leaf tea for diarrhea. They also used the bark externally to treat cuts and boils.

In traditional Iranian medicine, hazel leaves have a long history of use. In the past, they commonly used an infusion of hazel leaves to treat liver issues, but it’s still in use today for treating edema, hemorrhoids, phlebitis, and varicose veins.

Modern research supports the use of hazel leaves in traditional medicine. Studies have found that hazel leaves contain high levels of phytochemicals, mainly phenolic compounds, and may have antioxidant, anti-inflammatory, and antibacterial activities. Researchers in a 2023 study on the potential health benefits of hazel leaves predict that the leaves may have therapeutic effects for cancer, lipids, atherosclerosis, and diabetic complications.

Benefits of Hazelnuts

1. Promote Heart Health and offer cardioprotective benefits

Hazelnuts are considered cardioprotective, meaning they can help protect against heart disease. This is due to their high content of beneficial nutrients like monounsaturated fats, omega-3 fatty acids, antioxidants, and fiber. These components work together to reduce risk factors for heart disease, such as high cholesterol, inflammation, and high blood pressure.

Tree nuts are a well-known combatant in the fight against heart disease, and hazelnuts are no exception. There are a handful of vitamins and minerals found in hazelnuts that promote heart health.

Aside from being a great source of fiber, they contain a large amount of monounsaturated fatty acids, which help reduce LDL cholesterol (the “bad” kind) and increase HDL cholesterol (the “good” kind).

Studies conducted by the American Society for Nutrition and published in the European Journal of Nutrition showed that diets high in hazelnuts and other tree nuts resulted in lowered LDL cholesterol, reduced inflammation and improved blood lipids. The American Heart Association also recommends that, for optimum heart health, the majority of the daily fats that individuals should consume should be monounsaturated fats, which are the same found in hazelnuts.

Hazelnuts also contain a considerable amount of magnesium, which helps regulate the balance of calcium and potassium and is crucial to blood pressure.

2. Help Manage Diabetes

When laying out a diabetic diet plan, it’s important to focus on choosing monounsaturated fats over trans fats or saturated fats. Hazelnuts are a great source of these good fats, and eating recommended portions of hazelnuts as a substitute for more damaging,”bad” fat foods is a great way to ensure you gain the benefits of good fats without worrying about gaining additional weight.

In a 2015 study published in the American Journal of Clinical Nutrition, an interesting result occurred regarding how diabetics reacted when supplementing their daily diets with tree nuts. Like other studies, it was concluded that individuals introduced to heightened nut consumption in their diets experienced lowered cholesterol levels. The surprising variable was that higher nut doses provided a stronger effect on diabetics, doing more to lower blood lipids than for non-diabetics.

Diabetics with high cholesterol should consider adding hazelnuts and other tree nuts to their daily diets. Proven to improve glucose intolerance, hazelnuts’ high levels of manganese are also helpful in the fight against diabetes when used as a diet supplement.

Hazelnuts are also a great source of magnesium, which has been proven to decrease the risk for diabetes.

3. Filled with Antioxidants

Hazelnuts have many vitamins and minerals that are powerful antioxidants. Antioxidants wipe out damaging free radicals in the body and help prevent major disease and illness, like cancer and heart disease.

The hazelnut is also a great source of vitamin E, which helps fight aging and disease by reducing inflammation.

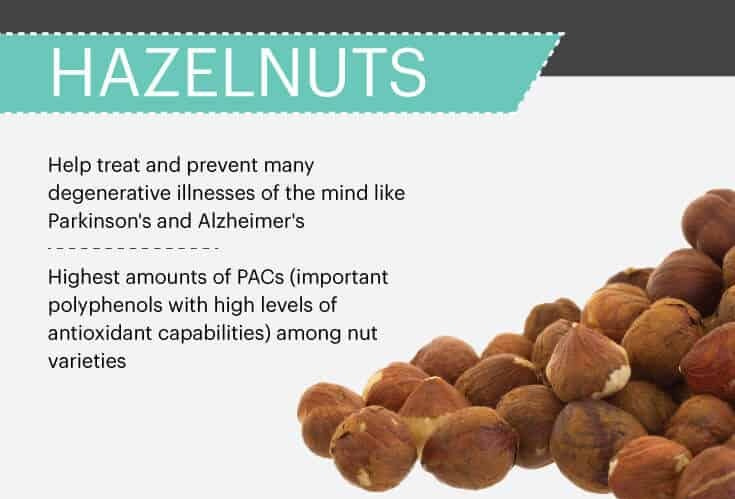

One serving of hazelnuts can provide almost an entire day’s amount of manganese as well, which is not an antioxidant but is a huge contributor to enzymes that are. Hazelnuts have the highest content of proanthocyanidins (PACs) as well, a class of polyphenols that gives foods like red wine and dark chocolate their “astringent mouth feel” compared to other nuts.

Studies have shown how PACs have a significantly higher level of antioxidant activity compared to others, like vitamin C and vitamin E, which only work in certain environments.

They also are shown to fight aging and help stave off disease. PACs are known for their ability to help treat urinary tract infections as well.

To get the most antioxidants from hazelnuts, it’s best to consume them with the skins present.

4. Boost the Brain (offering Neuroprotective and Neuro-regenerative benefits)

Hazelnuts should be considered a brain-boosting powerhouse. They’re full of elements that can help improve brain and cognitive function and help prevent degenerative diseases later in life.

Because of high levels of vitamin E, manganese, thiamine, folate and fatty acids, a diet supplemented with hazelnuts can help keep your brain sharp and working at its best, making hazelnuts excellent brain foods.

Higher levels of vitamin E coincide with less cognitive decline as individuals age and can also have a major role in preventing and treating diseases of the mind like Alzheimer’s, dementia and Parkinson’s. Manganese has been proven to play a major role in the brain activity connected to cognitive function as well.

Thiamine is commonly referred to as the “nerve vitamin” and plays a role in nerve function throughout the body, which plays a key role in cognitive function. It’s also why thiamine deficiency can be damaging to the brain.

The high levels of fatty acids and protein aid the nervous system and also help combat depression.

In a study published in Nutritional Neuroscience, hazelnuts were tested for their neuroprotective qualities. When provided as a dietary supplement, hazelnuts were able to improve healthy aging and memory and hinder anxiety.

In addition, a systematic review published in 2021 examined nut consumption’s effects on cognitive performance. While results were ultimately inconclusive in regard to how much eating nuts can protect cognition throughout life, the results suggest nuts do benefit cognition in “individuals at higher risk of cognitive impairment.”

Hazelnuts are also folate foods. Known for its importance for spine and brain development during pregnancy, folate also helps slow brain-related degenerative disorders in older adults.

5. Help Prevent Cancer

Thanks to hazelnuts’ high number of antioxidants, they’re important cancer-fighting foods. Studies have shown vitamin E’s capabilities for helping decrease risk for prostate, breast, colon and lung cancers, while also preventing the growth of mutations and tumors. Vitamin E has also shown possibilities of aiding in multi-drug resistance reversal and cancer treatments.

In other studies, manganese complexes were found to exhibit potential anti-tumor activity. For example, research conducted by the School of Chemistry and Chemical Engineering at Jiangsu University in China and published in the Journal of Inorganic Biochemistry found that manganese complex could be a “potential antitumor complex to target the mitochondria.”

Meanwhile, a 2023 study published in Advanced Biomedical Research determined that “hazelnut oil appears to cause the death of cancerous cells through an apoptotic mechanism.”

6. Hazelnuts offer Ocular-Protective benefits (they improve eye health)

Hazelnuts are good for eye health due to their high vitamin E content. Vitamin E is an antioxidant that helps protect the eyes from harmful molecules and slows the progression of age-related macular degeneration (AMD) and cataracts.

Vitamin E:

Hazelnuts are a good source of vitamin E, an antioxidant that helps neutralize free radicals in the body. Free radicals can damage eye cells and contribute to the development of eye diseases like AMD and cataracts.

Other Nutrients:

Besides vitamin E, hazelnuts also contain other nutrients that are beneficial for eye health, such as zinc and omega-3 fatty acids. These nutrients contribute to overall eye health and protect against vision problems.

7. Hazelnuts offer Osteoprotective and Osteoregenerative benefits (they improve bone health)

hazelnuts are beneficial for bone health. They contain essential minerals like calcium and magnesium, which are crucial for maintaining bone density and strength. Regular consumption of hazelnuts can help reduce the risk of osteoporosis and fractures.

Calcium:

Hazelnuts are a good source of calcium, which is a primary building block for bones and teeth.

Magnesium:

Magnesium plays a vital role in bone health by regulating calcium and potassium balance, crucial for preventing bone loss.

Other Nutrients:

Hazelnuts also contain other bone-friendly nutrients like vitamin E, manganese, and phosphorus.

Antioxidants:

The antioxidants in hazelnuts help protect bone cells from damage and promote healthy bone metabolism.

Reduced Risk of Osteoporosis:

By providing essential nutrients and promoting healthy bone metabolism, hazelnuts can help reduce the risk of osteoporosis and fractures.

8. Hazelnuts enhance Fertility and Reproductive Health

Hazelnuts benefit reproductive health in both men and women due to their rich nutrient profile. They are packed with antioxidants, vitamins, and healthy fats that improve sperm quality, potentially increase fertility, and support overall reproductive health.

For Men:

Hazelnuts are a good source of vitamin E, zinc, and selenium, all of which are crucial for sperm health. These nutrients help protect sperm from damage caused by free radicals and maintain the structural integrity of sperm, which is essential for successful fertilization.

Potential Increase in Sperm Count:

Some studies suggest that consuming nuts, including hazelnuts, may increase sperm count and improve sperm motility.

Testosterone Regulation:

The nutrients in hazelnuts also play a role in regulating testosterone levels, which are vital for male fertility.

For Women:

Supportive of Overall Reproductive Health:

Hazelnuts contain omega-3 fatty acids, folate, and antioxidants, which are important for reproductive health in both men and women.

Potential Fertility Boost:

Some research indicates that foods rich in protein, lipids, and antioxidants, like hazelnuts, help improve fertility in women.

Hormone Regulation:

Hazelnuts also contain minerals like selenium, iron, zinc, and calcium, which can contribute to hormonal balance, a crucial factor for reproductive health.

“The greatest healing provided by hazel is found within its atmosphere. Being near hazel trees or meditating upon a piece of hazel brings spirit alive and allows us to quickly cast off the old and move on to the new. Hazel's atmosphere exudes exhilaration and inspiration.” - source

History and Cultural Relevance of Hazel:

“Hazel was one of the first trees to colonise the land after the end of the last Ice Age,” writes Gabrielle Hatfield, “and for a great period of time it would have been one of the most abundant tree species.”

Humans have been enjoying hazels since prehistoric times and research confirms that hazelnuts provided a staple source of food in cultivated (regenerative fire managed food forests in northern Europe and North America) before the days of wheat. Evidence of large-scale Mesolithic nut cultivation and processing, some 9,000 years old, was found in Scotland and Hazels have been used extensively across the temperate zone throughout all civilizations.

After the glaciers retreated, the continent was a cold tundra of lichens, mugwort, dwarf willow, and sea buckthorn - populated by prehistoric megafauna and migratory bands of humans returning from their Ice Age refugia in the mountains. Around 9,600 BCE, global temperatures rose 7°C in less than a decade, allowing for temperate deciduous forests to return. Populations of Mesolithic humans expanded rapidly across Europe, bringing their most prized plant with them: hazel.

Much as peaches, once introduced, were spread across North America by indigenous people in a matter of decades, the pollen record shows that hazel (Corylus avellana) suddenly becomes ubiquitous across Europe as soon as the climate warmed, brought to every corner of the continent by pre-statist indigenous European cultures. Hazel was the original Tree of Life for Mesolithic Europeans.

Its branches, tall and flexible but slender enough to cut with a flint axe, were used for tools and firewood. Mesolithic thatched huts were often made with hazelwood beams. From cradle to grave, the people of Mesolithic Europe relied on hazel more than any other single plant. Excavations of habitation sites from this period can turn up hundreds of thousands of roasted hazelnut shells and containers where viable seeds were gathered and stored for planting. For over five thousand years, this single plant was the lifegiver to nearly all of Europe’s people.

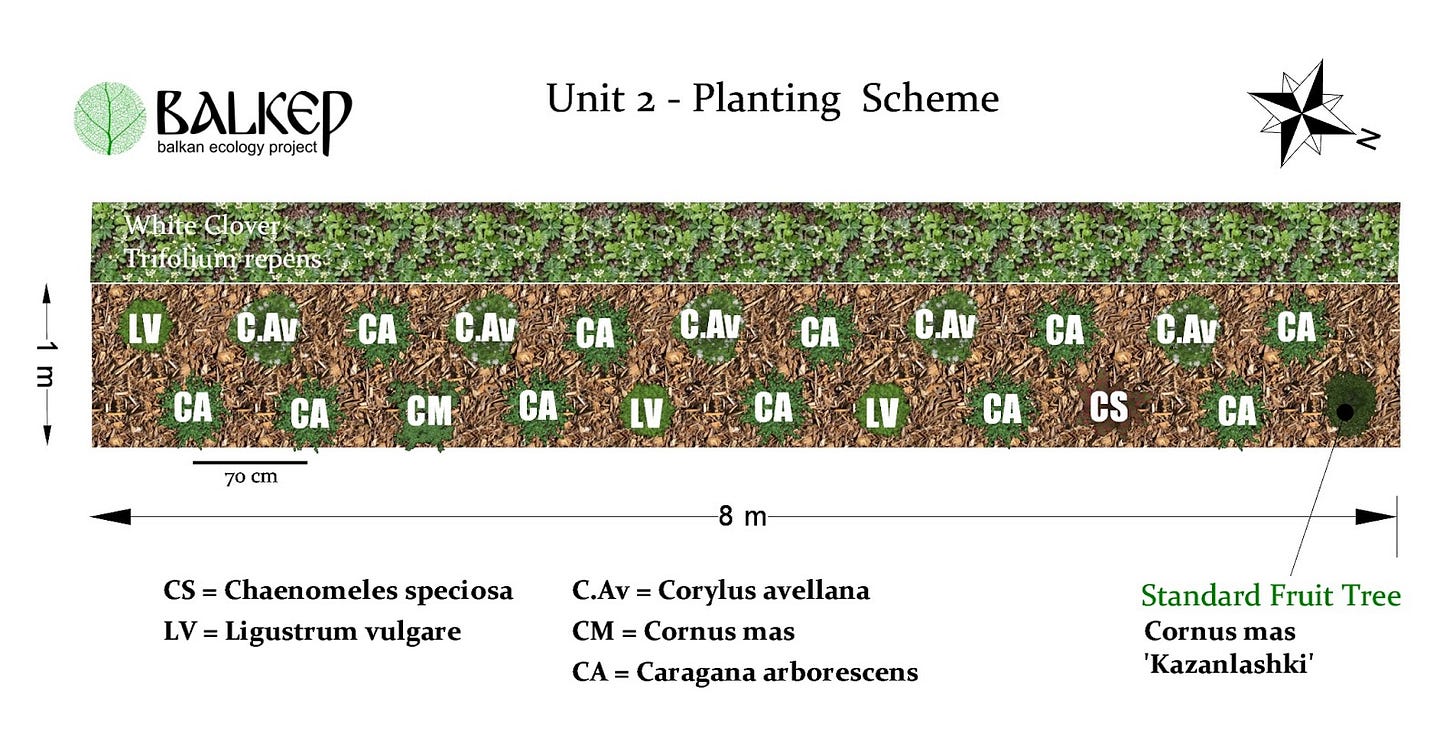

Whereas modern industrial agriculture is descended from a distinctly imperialist Roman plantation system based on slave labor, European forest garden food production systems (which cultivated Hazel along side other nuts and fruit) are the direct descendants of the indigenous forest gardens of pre-agricultural Europe. Since the Neolithic Revolution, an assortment of farming systems in Europe that relied heavily on monocultures and a handful of finicky staple crops often ended abruptly and violently. The diverse forest gardens of indigenous peoples of Europe, however, have quietly shrugged off ten thousand years of turbulent changes.

In addition to hazel, Mesolithic people saved seeds from, cultivated and used up to 450 different species of edible plants - many of which were common plants of forest edge habitats. Acorns, Hazel nuts and Wild vegetables (many of which are considered weeds today) like nettle, knotweed, lesser celandine, dock, lambs quarters, fruits like sloe plum, rowan, hawthorn, crabapple, pear, cherry, grape, raspberry, and tubers of aquatic plants were all part of the Mesolithic diet. These European native plants were not only utilized, but also actively cultivated selectively by Mesolithic indigenous communities in what is now Europe for the same reason they are often seen as weeds today: they’re extremely resilient, aggressive, and adaptive species that can be encouraged to grow with minimal effort.

These were not bands of starving cavemen constantly on the precipice of death, but rich and resilient societies that had a much more diverse diet than most present-day Europeans. Researchers found that a young girl who died 5,700 years ago in southern Denmark ate duck and hazelnuts - a far richer (and tastier) diet than most kindergarteners in Western countries have today.

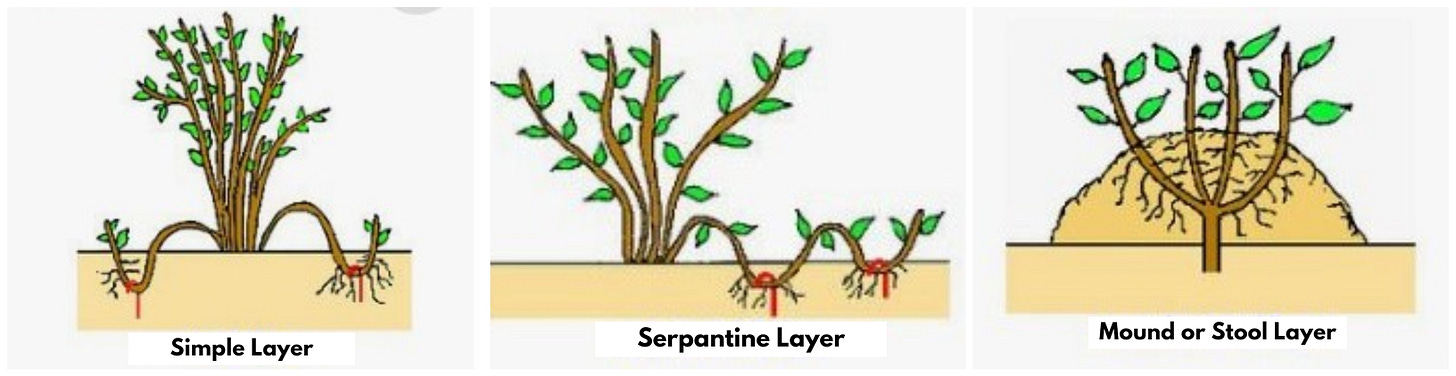

After helping to create Europe’s forests by bringing favored plants like hazel with them, they continued to manage their landscape with hand tools, seed saving practices and fire. Europe was not a pristine wilderness, but a continent of handcrafted nut orchards and semi-wild forest gardens carefully managed for thousands of years. This tracks with common themes around the world: indigenous people in Australia, North and South America, and elsewhere have used fire, seed saving and layering (asexual propagation of plants) and specialized hand tools to achieve unprecedented levels of environmental stewardship and management for millennia.

Areas around settlements and camp sites were regularly burned to limit the encroachment of the forest, replanted with choice species (like Hazel) and to favor self-propagating food-producing forest edge trees species as well. These controlled burns established open park-like habitats, which could lead to a tenfold increase in the amount of wild game animals present, creating greater opportunities for hunting red deer, wild boar, and aurochs.

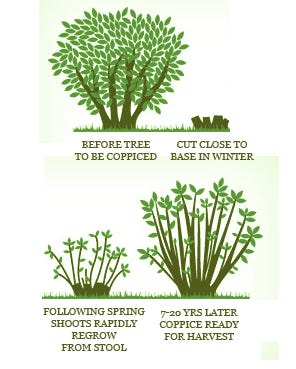

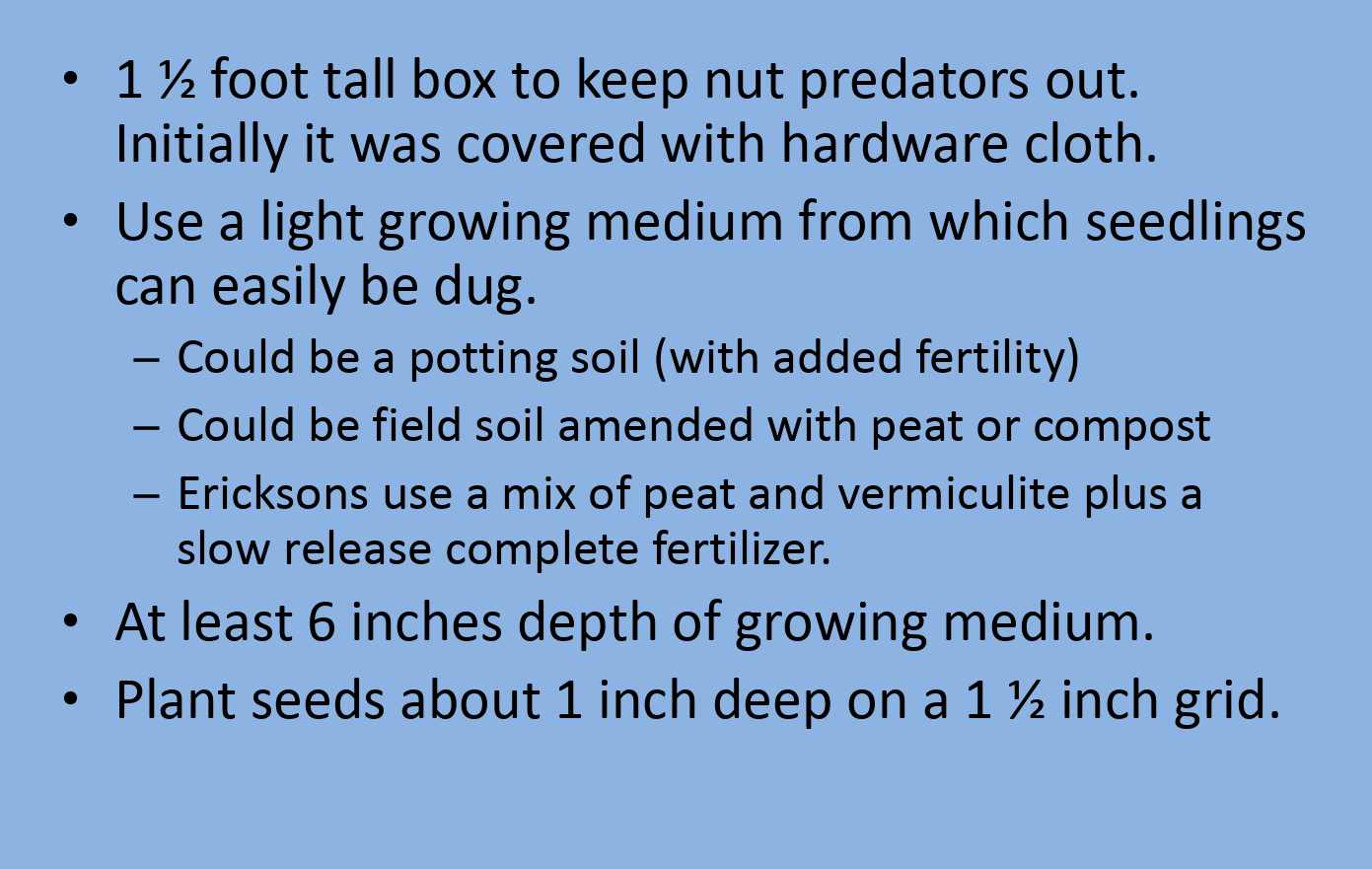

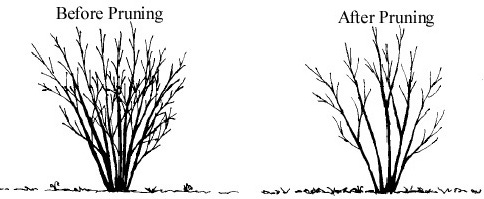

Coppicing was another important strategy for managing the Mesolithic forest garden. Certain trees and shrubs, like hazel, can be cut to the ground every few years. Instead of hurting the tree, this effectively rejuvenates it, allowing the plant to live far longer than it would if unmanaged. Hazel in a wild state generally lives around 70 or 80 years, but with regular coppicing it can thrive and produce wood and nuts for centuries. Willow, another plant with many uses and benefits, is managed in this way as well. Coppicing lent itself perfectly to Mesolithic technology: without saws or metal tools, it was far easier to harvest small-diameter trees and branches than large trunks. For cultivating or regenerating patches of wild vegetables or semi-domesticated grains, Mesolithic Europeans also had a wide range of hand tools at their disposal, including flint axes, wooden and antler hoes, mattocks, and digging sticks. The open forest gardens that surrounded Mesolithic camp sites and settlements could be managed this way for millennia.

The practice of coppicing trees did not end in the Mesolithic either. The wild willow-thick streambanks became managed willow beds that were planted with cuttings of the best plants and grown along side Hazel for both food and weaving materials. These willow and hazel beds were coppiced every year for crafts and toolmaking. Hazel and Willow Wicker basketry became such an elevated artform in the British Isles that fine Celtic baskets were imported by Roman aristocrats. The word ‘basket’ itself (originally ‘bascauda’) is one of the only words of Celtic origin in the deeply colonized English language. Coppice woods of chestnut, linden, hazel, and other useful species have remained an essential and ancient part of the British landscape, providing materials for housing, tools and crafts, charcoal production, mushroom cultivation, and even rich pockets of endangered biodiversity.

Mesolithic people were not unaware of grain growing - they had been experimenting with it for millennia before Near Eastern farming cultures entered the scene. The spread of farming, therefore, was not due to the supposed superiority of grains, but because repeated periods of shifts in weather (large ice sheets melting) and the resulting social chaos pushed Mesolithic Europeans to adopt new ways of life to survive.

In other areas, the adaptation of the Mesolithic forest garden took the form of fruit-chestnut silvopastures created as semi-natural open forests. These included diverse nut and fruit assemblages (such as chestnut, carob, almond, fig, olive, hazel, cork oak) that allowed for livestock grazing beneath them. A culture of chestnut forest management in Corsica shows how the use of perennial nut crops as a staple has never left Europe.

Indeed, Mesolithic indigenous communities continued to live peaceably side-by-side with “Neolithic” farming communities for thousands of years before some adopted monoculture based agriculture. As in many parts of Europe, the cultures of Mesolithic Sweden had depended on hazelnuts for millennia - with some scholars even dubbing this period the “Nut Age.” When Neolithic grain-farming communities entered southern Sweden around 5,500 BCE, the native hazel-based cultures continued to practice their traditional ways for another 1,600 years. It was only when a period of dramatic cooling began that hazel populations in the region plummeted and Mesolithic communities, now without their sacred life-giving tree, adopted grain farming by 3,900 BCE. This was a story repeated throughout Europe. And while nearly all of Europe eventually came to adopt grain farming, the resilience of these Mesolithic cultures over the course of millennia demonstrates that hazelnuts are perhaps the best option for a perennial crop that can replace grains in a temperate climate.

“Hazelnut still remained important in rural Sweden until recent times; and there are a number of placenames and surnames that come from it, Hasselblad ‘Hazel leaf’ for example.” -

Little wonder the hazel tree has become deeply entrenched in our ancient history, beliefs and customs.

Hazel forests provided materials for making houses, fences, furniture, baskets and tools.

Its charcoal gave early people the thrill of gunpowder. The nuts have provided a valuable source of sustenance probably since prehistory.

People told epic stories about the tree and its fruit (hazelnuts) from ancient Greece to Medieval Europe, and it had a magical reputation in many traditions.

It is one of the characteristic trees of the ‘Atlantic Hazelwoods’ that have been increasingly recognised as ‘Celtic Rainforest’ in recent years, and it has a long history of being used and loved by the people of Scotland.

The modern Gaelic name for the species is calltainn – mentioned in a short Gaelic rhyme about native trees and their favoured locations:

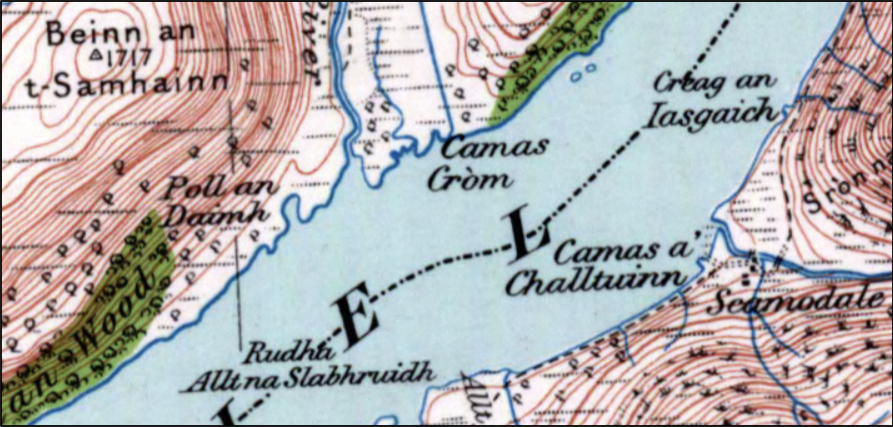

Seileach nan allt is calltainn nan creag,

Feàrna an lòin is beithe nan eas,

Uinnseann an dubhair is darach na grèine,

Leamhan a’ bhruthaich is iubhar an lèana.

The willow of the streams and the hazel of the rocks, the alder of the damp meadow and the birch of the waterfalls, the ash of the shade and the oak of the sun, the lime of the hill and the yew of the plain.In the form calltainn, the hazel is found named in several locations on the landscape e.g. Camas a’ Challtainn ‘the bay of the hazel’ on Loch Shiel and Àirigh a’ Challtainn ‘the shieling of the hazel’ in Glen Strae. However, students of the ‘arboreal alphabet’ of the Gaels will know that the letter ‘C’ in ancient times was represented by an older name for the hazel – coll or call. This is also present in old place-names such as Badcall i.e. Bad Call ‘hazel copse’, found in at least three locations in the North West Highlands (although the species does not give us the name for the island of Coll or the village of Coll in Lewis).

In Lowland Scotland there are numerous examples of Cowie and Cowden names, many of which are likely to have originated in a Gaelic reference to hazels. Watson was able to prove this in the case of Cowden near Comrie in Perthshire, which was Coldon in old documents and which Gaelic speakers in his day still referred to as A’ Challtainn ‘the hazel wood’.

Hazelnuts also have a special place in Gaelic folklore in both Scotland and Ireland, with a particular form being known as cnò an eòlais ‘the nut of knowledge’. It was by eating the flesh of a salmon that had itself consumed some of these special nuts, that Fionn mac Cumhail, the great legendary leader of the Fianna, achieved his superior knowledge. In one of the great legends of Skye, the warrior queen Sgàthach and her student Cù Chulainn fought some stupendous battles with neither coming out on top – until each of them, by taking a meal of roasted hazelnuts, acquired the wisdom to discontinue the conflict!

Yet, for all its vaunted power, in the language of flowers, Hazel signifies reconciliation and peace.

The Hazel tree has provided people with food to eat, flowers to heal, and wood to build for many centuries. This is true for the indigenous peoples of Europe as well as those indigenous to Turtle Island.

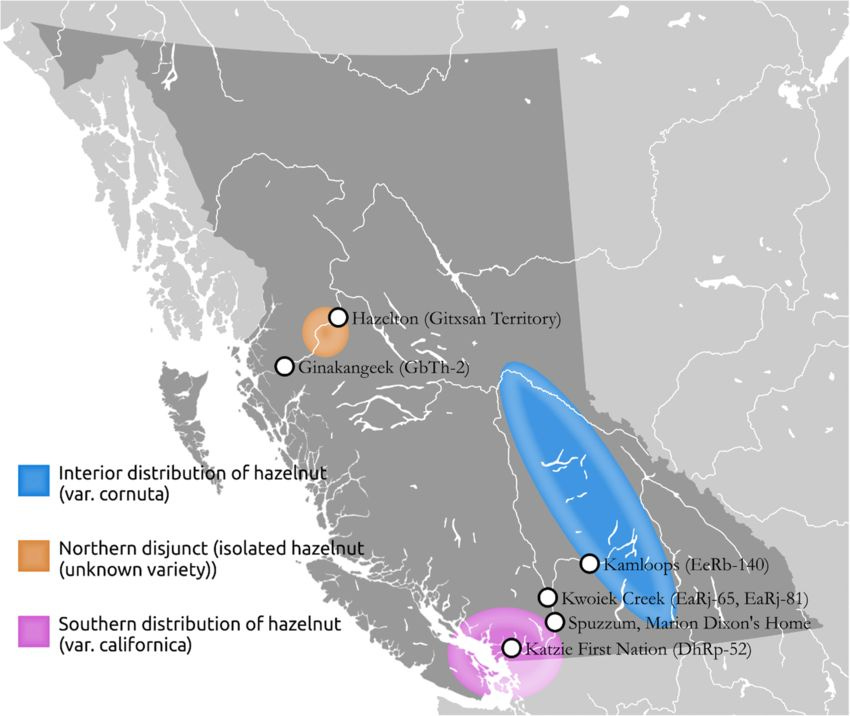

Scientists have now discovered 7000 thousand year old food forests in northern BC, Canada (yes that is right, seven thousand). These food production systems were designed, installed and tended reverently for centuries until their creators and stewards were forced to flee.

The hazelnut tree has long been a part of the landscape in parts of British Columbia. A 19th-century settler gave the village of Hazelton in northern B.C.'s Skeena region its name because of the abundance of hazelnuts in the area.

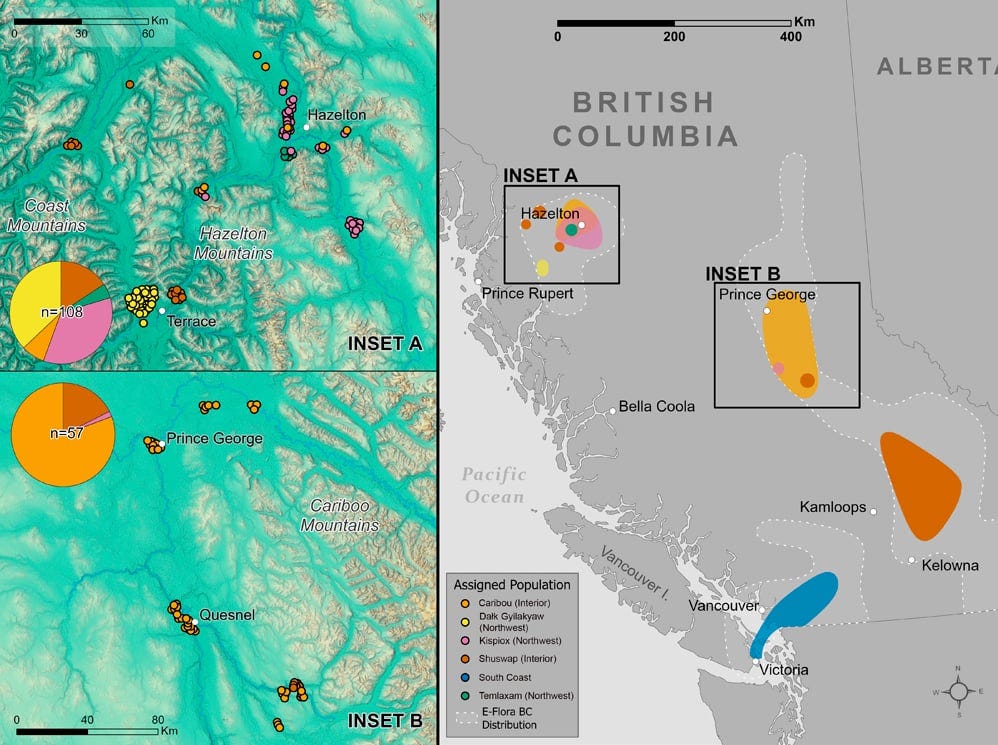

A new study published in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Science indicates Indigenous peoples in what is now B.C. had been cultivating the beaked hazelnut for thousands of years. According to study researchers, the findings "challenge settler colonial views about past Indigenous land-use practices."

The findings indicate hazelnuts had been transplanted and cultivated for at least 7,000 years by Gitxsan, Tsimshian, and Nisga'a peoples.

Study co-author Chelsey Geralda Armstrong, assistant professor of Indigenous studies at Simon Fraser University, says the research emphasizes Indigenous peoples' contributions to the creation and maintenance of the region's ecosystems and "cuts through assumptions of B.C. and the Northwest Coast being wild and completely untouched."

"We've known for a long time, and in fact, a lot of Indigenous communities know, that Indigenous stewardship practices helped shape plant species distributions and kept populations of salmon healthy, all of that," Geralda Armstrong said.

"So, our research is adding to that by challenging the dominant narrative, which is that, 'Oh yeah, this hazelnut is wild, and it's just growing here.'"

For the study, researchers sequenced the DNA of more than 200 hazelnuts and found five genetic subgroups, many of which could be traced to locations far apart from each other, indicating the nuts weren't distributed naturally through birds and squirrels but through concerted efforts by Indigenous peoples.

The study also highlights linguistic evidence, noting that the word for "hazelnut" used by the Gitxsan and Nisga'a in the northwest was borrowed from Coast Salish territories in the south, suggesting a trade in nuts.

Armstrong started collecting hazelnut leaf tissue samples from around the province a decade ago. Her findings were “so confounding” that it led her to dig deeper by examining linguistics and archeology associated with the food staple, she said.

The research could have big implications for Indigenous land claims, Armstrong added, by challenging existing narratives that First Nations lived passively on the landscape rather than actively tending it.

Her research reveals that the region’s early inhabitants moved hazelnuts long distances and managed the shrubby plants, creating and maintaining “large-scale ecosystems and sometimes entire watersheds through prescribed burning and forest clearing, transplanting [and] rock wall constructions” to foster perennial plant species.

The study examined three regions. On the south coast, it found just one genetic cluster of hazelnuts. In the Interior, there were two.

But most intriguing was the complexity in northwest B.C., where five distinct genetic hazelnut clusters are scattered around the area surrounding Temlaxam — a region that today includes the community of Hazelton.

Armstrong said the findings were the “opposite of what you’d expect” from plants in an isolated grouping, which would normally lack genetic diversity.

“The pattern here with increased genetic diversity... that’s huge unto itself,” she said. “When you drill down and you start to look at the ethnographic record, the archeological record, things start to come together in this really neat way.”

The same study that unearthed the 3,500-year-old landslide at Seeley Lake, about 10 kilometres west of Hazelton, also found that hazelnut pollen abruptly appeared at the location about 7,000 years ago.

The hazelnuts also overlap with ancient village sites, which form islands of distinct hazelnut groupings in the northwest.

The Kispiox Valley and Hazelton area had its own unique hazelnut, which continued a distance down the Skeena River before disappearing.

The next cluster appeared at Kitselas Canyon, a national historic site east of Terrace with a vast archeological record. To the west of Terrace, at the ancient Kitsumkalum village of Dałk Gyilakyaw, a distinct population exists that is not related to any other hazelnuts.

“It is exclusively associated with a village site,” Armstrong said. “Then, when you go up to the Nass, same thing — there’s nothing until you’re at Gitwinksihlkw.”

Hazelnuts travelled long distances

Hazelnuts from three large village sites — Gitwinksihlkw and Gitlaxt’aamiks in the Nass Valley and Kitselas Canyon east of Terrace — are all closely related to those in the Shuswap, roughly 700 kilometres to the southeast.

A linguistic review indicates it wasn’t only the hazelnuts that travelled those distances. The term for hazelnut also moved with them. The Gitxsan (sgan-ts’ek’ or sgan-ts’ak’) and Nisga’a (ts’ak’a or ts’inhlik) bear similarities with the Proto-Salish word for hazelnut, s-ts’ik’ or s-ts’ik.

Jacob Beaton, the executive director of the Indigenous Food Sovereignty Association and a member of the Ts’msyen Nation, grew up in the Hazelton area, surrounded by the proliferating nuts.

“I remember my mom, who’s First Nations, telling me when I was a kid, if I could pick a whole bucket of hazelnuts, that she’d make homemade Nutella,” he said. “Those stories exist everywhere here in the First Nations communities of picking and harvesting hazelnuts.”

While Beaton always knew about the nuts’ existence, he never understood why they were so populous in the area. But he always wondered. He said there was “massive resistance” in the scientific community to the idea that they were brought there by Indigenous Peoples.

Beaton, who wasn’t directly involved in Armstrong’s research, said he had previously seen research indicating that First Nations had tended forest gardens in the area for at least 800 years. He said he was “very, very surprised” by Armstrong’s findings because they date back thousands, instead of hundreds, of years.

“To have this hazelnut study come out and learn that it’s around 7,000 years that the First Nations brought hazelnuts and planted them here was insane,” he said, noting that it meant First Nations were growing food “before ancient Egyptians were planting their wheat fields.”

These indigenous people were cultivating these food forests (at the same latitude as where BC meets Alaska) before wheat farming began in Egypt. They did not only provide for the 7th generation, they are providing for the 300th generation. That is the potential of food forest design.

These food forests contain hazelnuts, wild cherry, elderberry, wild ginger, wild rice root, soapberry, thimbleberry, red huckleberry, crabapples, serviceberries, blueberries, cranberries, hawthorn, rhodiola rosea and medicinal herbs.

These food forests still persist and produce abundant (and nutrient dense) Free Food today.

That is a form of horticulture and social technology we should all be striving to learn from and apply locally.

The fact they could create such a resilient, stable and nutritionally diverse food production system that far north shows us how we are only limited by our imagination and pattern recognition skills with regards to food forest design.

We can do it using a range of different species to fill the relevant ecological niches in our bioregion and we can effectively boycott the corporate/statist hegemony through decentralizing our access to food and medicine, blending our gardens with forest ecology, sharing the abundance and planting the seeds for an emergent regenerative subculture/parallel society.

Erichsen-Brown notes in Medicinal and other uses of North American Plants: A Historical Survey with Special Reference to Eastern Indian Tribes the extensive uses of Hazelnut among Native Americans in North America. Archeological evidence demonstrates Hazelnuts at an Iroquan site and in caves in what is now Ohio in Pennsylvania; this evidence dates from 800-1400 AD that large amounts of nuts were consumed by the tribes living here. Hazelnuts were dried, ground up, made into meals and gravies, and used to create mush. The oil was also used for hair and mixed with bear grease by the Iroquois.

Medicinally, the Hurons used a bark poultice of the hazelnut tree for ulcers and tumors. The Chippewa used hazel and white oak roots combined with the inner bark of chokecherry and the heart of ironwood for hemorrhages or serious lung conditions. Similarly, the Ojibwa used the bark poultice on cuts.

The inner bark was used by the Chippewa (along with butternut or inner bark of white oak) as a dye for blankets, rushes, and more. A recipe given in Erichson-brown is to use the hulls from the nuts to set the black dye of butternut when boiled with tannic acid. The Chippewa and the Ojibwe also made drumsticks of hazel along with brooms and twig baskets. The bark was also used to expel worms, in a similar fashion to walnut. (source)

“The hazel tree has an unusual history. The last ice age forced the land to rest. Frost action, combined with the scouring of glaciers, pulled the riches of macro- nutrients from the surface of rocks. After the ice receded, the land was as fresh as a new pin. The low-growing hazel was perfectly suited to be the first crop of forest.

Scientists have taken core samples of the earth from periods just after the last ice age. These samples, every- where, are contaminated with a huge amount of pollen from hazel woods that seemed to drift in shoals on the surface of the soil. Some of it would have come from climatic stress on the trees that forced them to reproduce; the other factors for that first efflorescence of pollen are unknown. We are now witnessing releases as bountiful as they were at the end of the last ice age. Make of that what you will.

The Celts loved to eat hazelnuts. Indeed they were a favourite table treat for Celts from Ireland and all across their civilization into Turkey. They were also enjoyed further afield in China and Japan.

“Within European folklore the Hazelnut has been associated with fertility, wisdom, love, luck, birth, and regeneration. Blooming twice each year, the Hazel was seen as a sign of abundant fertility. The nuts were used for divination around love and marriages. And it was common to throw hazelnuts and carry hazel wands at weddings to ensure fertility for the new couple. Teutonic people associated the Hazle with Thor, the god of storms, lightning and the sky. The Hazelnut itself was believed to have the ability to avert as well as hold the life giving, fertilizing power within storms. And Germanic peoples placed the nuts on windowsills to avert lightning from the home.” - Earthen Venus: On Hazelnut love charms, Mandrake root amulets, Wild Women and Deer Goddesses by

One thing the Roman’s predecessors (the Greeks) apparently did get right is that they also associated the Hazelnut with fecundity and fertility.

Modern research confirms that Hazelnuts benefit reproductive health in both men and women.

Thus, after discovering this fact while researching for my Hazel article, I went back and updated my article on Fertility and Reproductive Health Enhancing whole foods and naturally occurring compounds with pertinent info on Hazel’s benefits in that realm (specific part of article updated linked here (screenshot shown below).

In one part of Albion, there were Celts that practised a sophisticated method of two-tier farming involving both hay and hazel. Hazel trees enjoy the stability of roots feeding undisturbed in a field of grass. A hedgerow of hazel protects the hay from blowdown. So both grew together to benefit each other-the better the hay crop, the larger the nutmeat. The hay was cut, dried and harvested first. The ripe hazelnuts were gathered immediately afterwards.

Hazel trees travelled with all of the old civilizations. The fresh bark of the hazel tree was removed by the Greeks and used to write on. The word passed along in language, today making an appearance in "protocol," from protokollen: the first sheet of papyrus roll from which a document of record is made.

Before the advent of drilling machines and drilling rigs with pounders or diamond bits, people depended on instinct alone to find water underground. Individuals who inherited this instinct for discovery were of great value to any community. The water for my well in Ontario was found by the local dowser (using a hazel fork) who also happened to be the water driller. After he estimated the greatest flow rate per minute and per hour, he drilled the well and the house went up over it.” - Diana Beresford-Kroeger from To Speak for the Trees

In Gaelic tradition, Hazel is one of the "nobles of the wood" (airig fedo), a classification of trees in pre-colonial Gaelic law that signifies their sacred importance and value as a being that teaches, provides nourishment and is protected against exploitation.'

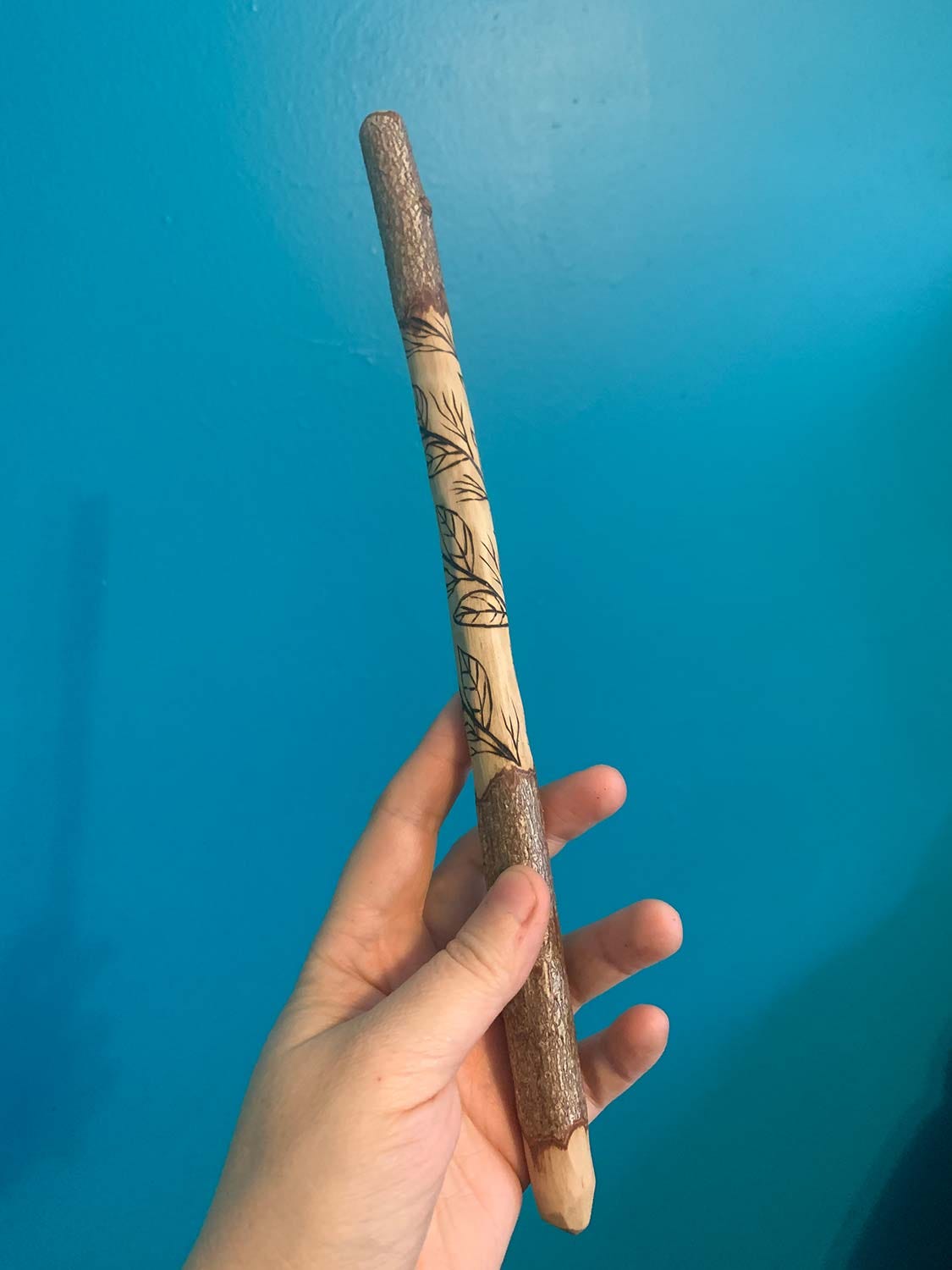

Hazel trees often grow by water which has long been associated with intuition – dowsing rods are often made of hazel wood.

There is a story from the land of my ancestors on the Isle of Skye about hazelnuts.

(for a Gaelic reading of this story, go to this website)

“There was at one time a strong, powerful woman living on the island. Her name was Sgàthach. She was living in Dunscaith Castle in Sleat. She had a fighting school.

The school became internationally famous. The Ulster hero, Cuchullin, heard about it. He was renowned in Ireland. He was brave and strong.

Cuchullin went to Skye in three bounds. He was expecting Sgàthach to give him a warm welcome. But she didn’t. He wasn’t famous in Scotland like he was in Ireland.

Cuchullin was angry. He was fighting with the other students in the school. He defeated them. Then Sgàthach noticed him. She gave him permission to fight her daughter. After two days and a night, Cuchullin defeated her daughter.

Sgàthach herself came. She and Cuchullin fought for two days and a night. But neither of them was victorious.

Sgàthach’s daughter obtained deer milk. She made cheese with it. But neither her mother nor Cuchullin ate any of the cheese. The daughter sent out heroes to kill a deer. She roasted the meat. But neither Sgàthach nor Cuchullin ate any of it.

Then she sent out the heroes to hazel trees on the side of a mountain near Sligachan – Broc Bheinn. They brought back hazel nuts. The daughter roasted another deer. She stuffed the deer with roasted hazelnuts. Sgàthach and Cuchullin ate that.

Sgàthach hoped, with the knowledge from the nuts, that she would defeat Cuchullin. Cuchullin hoped, with the knowledge from the nuts, that he would defeat Sgàthach. But when the two of them ate the nuts, they gained the knowledge of peace. They pledged they would no longer fight each other. Perhaps we should all eat more hazelnuts!”

“Hazel in the Western Magical Traditions

While Hazel is a critically important tree in the mythology and magical tradition of Druidry and in Europe more broadly, The Hazel is one of the sacred trees identified by the druids as a tree tied to wisdom and the flow of Awen, and it is one of the sacred trees found in the Ogham. But here in North America, despite having our own native hazels (American Hazelnut and Beaked Hazelnut), we often turn our eyes towards Europe’s mythology and understandings. Thus, in this post, I’d like to share more about the American Hazelnut, and the ecology, uses, herbalism, magic, and myths of this most sacred tree.

In Celtic mythology, Hazel was an extremely important tree and tied directly to the mythology of the druid tradition. In Irish mythology in the Finnean cycle, it is written that the Hazel tree is the very first tree to come into creation and that all of the knowledge of the world was contained in the Hazel tree. The Salmon of Wisdom (An Bradán Feasa) lived in the Well of Wisdom (Tobar Segais) which was surrounded by nine sacred Hazel trees with their wisdom-containing nuts. The nuts of the trees dropped into the water and eaten by the Salmon. The first person to catch and eat the Salmon would gain this knowledge. While many tried and failed, Finnegas spent seven years fishing and finally caught it. Finnegas sets his apprentice, the young Deimne Maol, to prepare the fish but not to eat it. Deimne sets the fish upon a spit and begins to cook it. In the process of cooking when the fish is nearly prepared, Deimne burns his thumb and puts his thumb in his mouth to ease the pain–and, of course, acquires all of the knowledge from the Salmon of Wisdom. Deimne becomes Fionn mac Cumhaill (Fin McCool), the leader of the fabled Fianna and hero of many Irish tales. Those students of Welsh druidry will note the similarities between this story and the one describing how Gwion became Taliesin. In modern revival Druidry, the wisdom of the hazel and the Salmon of Wisdom in the sacred pool remains very important symbols of our tradition.

Greer notes in the Encyclopedia of Natural Magic that Hazel has been used by magicians extensively throughout the West. Hazel is best used for wands and various kinds of divination rods and sticks (including dowsing). Cut the hazel with a single stroke with a consecrated knife at sunrise on a Wednesday for the best effect. Hazelwood makes an excellent wand and transmits energy effectively. Greer also notes that the nuts are excellent for communing with Mercury or connecting with Mercurial energies. One area that I disagree with Greer about, however, is that he says that Witch Hazel (Hamamelis Virginiana) and American Hazel are interchangeable. In my own experience, while witch hazel became the traditional wood for dowsing rods, I do not believe these woods serve similar functions on the landscape, and thus, I have found them to have different magical qualities.

In Celtic Tree Mysteries, Steve Blamires notes that the wood was used for dowsers extensively in the British Isles. In the Ogham, hazel is noted as the “fairest of the trees” and is tied to the flow of Awen, divine inspiration, particularly for the crafting of poetry. The other thing Blamires notes, which I have not been able to find an original source for, is that there is a ritual by the druids called “Diechetel Do Chenaid” where chewing hazelnuts were used for inspiration or to learn of something lost. Finally, Hazel wands (probably due to their Mercurial connections) were used as a symbol for a herald.” - Dana O'Driscoll (from her post titled Sacred Trees in the Americas: American Hazel (Corylus americana) Magic, Ecology, and Sacred Uses)

(Perhaps the ritual of the Druids called “Diechetel Do Chenaid” where chewing hazelnuts were used for inspiration or to learn of something lost that Dana mentioned above can be explained (at least in part) from a modern neuroscience perspective via accounting for Hazelnuts cognitive function enhancing health benefits?)

“The most prolific legends concerning hazel come from Ireland and we look to that Emerald Isle for the greatest understanding of the tree. In Keating's History of Ireland we are told of a king named Mac Coll, meaning 'Son of Hazel', who was one of the three earliest rulers in Ireland. Mac Coll was one of the last of the kings of the Tuatha de Danaan. The hazel tree from which he took his name and power was specifically associated with wisdom. In the Triads of Ireland it is recorded that Coll (hazel) and Quert (apple) were the only two sacred trees whose wanton felling carried the death penalty. In the Dinnsbenchas, an early topographical treatise of Ireland, the hazel and apple are associated with oak, for the burst it. The Great Tree of Mugna is recorded as containing within itself the virtues of apple, hazel and oak.

Ireland was a land of trees in the time of Saint Patrick arriving.

Below is a verse from an Druidic poem which described the pre-colonial landscape of Ireland aka Éire (which means Abundant Land).

Look at the line in the ancient poem in the pic this video (also linked below) where a Druid is describing the lands of Ireland.

“Her forests that shed showers of nuts and all other fruit”

I have no doubt that Ireland once had beautiful food forests tended by the wise Druids and Gaelic folk that revered their "Nobles Of The Wood".

St. Patrick and his fellow Roman imperialists, weaponized the Christian belief system to be a tool for ethnic cleansing, deforestation and cultural genocide.

The video linked below shows footage of the last remnant of ancient oak, hazel, pine, beech, rowan and apple forests in Ireland (Tomnafinnoge Woods). That type of forest would have covered over 70% of the island prior to the arrival of the Roman Imperialists (such as St. Patrick, his disciples and their successors, that gave orders to cut down all the sacred groves and forested placed where Druids gathered).

The Roman Imperialists managed to destroy a good amount of the forests, but substantial amounts remained up until the arrival of the subsequent waves of the imperialist colonial forces of the Anglo-Saxons, Norman invasion and British Crown (the British Statists were the ones that really finished the job of decimating the Irish Hazel/Oak and apple food Forests).

Even as late as 1634, these woods were estimated to cover tens of thousands of acres, but from then on they were heavily exploited especially for British Navy shipbuilding.

In 1670, the woods were reported to be still extensive, “being nine or ten miles in length'“ and a valuation in 1671 found a total of 3905 acres (1579 hectares) of woodland there.

The forest is now 160 acres in size.

Most people think of Ireland and Scotland and think of endless rolling sheep pastures, but this only serves to show us how powerful generational amnesia and the shifting baseline syndrome can be in shaping prevailing perspectives.

There were no doubt food forests all over, and the groves that were sacred like the forests of Brocéliande and Caledon and others that were consecrated by pre-colonial Gaelic priests like the land in Wales dedicated to St Bueno.

Tomnafinnoge Woods (Ireland's Last Remnant of intact Oak/Apple/Hazel forest):

(For more on the progress of so called “civilization” read this)

Man's ancient use of the combinations of different trees, mixing their energies and qualities in order to obtain specific results, is shown in many excavations, especially those of burial mounds. From such a mound in Tresse, Brittany, charcoal of willow, hazel and oak was recovered in quantities enough to suggest that they had constituted the funerary pyre. One possible theory of their use is that they brought the qualities of enchantment, wisdom and royalty (respectively) to the funerary proceedings. In which case the Great Tree of Mugna may well have represented beauty, wisdom and strength.

Also recorded in the Irish treatise is a description of Connla's Well: a beautiful fountain, over which nine hazels of poetic art produced flowers and fruit [beauty and wisdom] simultaneously'. And we are told that as the nuts dropped from the trees into the water, so the salmon which lived in the well ate them, and whatever number of nuts the salmon swallowed, that many bright spots appeared on its body.

Other druidic legends concerning Connla's Well describe it as being under the sea and the source of the River Shannon, and tell us of the salmon of wisdom. This father of all salmon, when first going to the sea, was drawn to the magical well and his journeyings thence instilled in all future salmon their migratory genes. On reaching the well the salmon was given the great gift of wisdom by the well's guardians, for each of the nine hazel trees dropped a sacred hazelnut into the water. On swallowing these nuts the salmon became the recipient of all knowledge.

For another version of this story read:

The sacred hazelnut was so highly esteemed that it was called the food of the gods. That people desired to eat it, together with its mythical recipient the sacred salmon, is also apparent from old lore. Druidic land legend tells of Fionn, a pupil of a chief druid who lived on the River The haz Boyne. The druid master intended to eat the salmon of knowledge which he had caught in a deep pool, for its flesh, it was said, 'would make him conscious of everything that was happening in Ireland'. Young Fionn was ton fell told to cook the salmon for his master, but not to taste it. Yet while he pographic cooked the fish a blister appeared on its side and Fionn used his thumb to Dak, fort burst it. Having burnt his thumb, he automatically put it into his mouth for relief. Thus it was Fionn who received the salmon's gift of farsight, 'seeing all that was happening in the High Courts of Tara'. This story has a Welsh equivalent in the legend of Cerridwen and Gwion.

In Scottish legend there was a pair of mystical fishes which were regarded as the presiding spirits of a similar sacred well and its hazel tree guardians. These fish were holy and to kill or eat them was a grievous crime punishable by the gods themselves.

The atmosphere around a hazel tree is easily recognizable, for it is quick-moving and mercurial, like silvery fish. In south-west Britain country people say that 'silver snakes' surround the hazel's roots, which illustrates the swiftness of its energies. To understand this energy better we can look at the associations of hazel and the god Mercury, for the hazel- nut was especially sacred to him and is still held to be under the influence of the planet Mercury.

Mercury, or Mercurius, is often given the same attributes as the Greek god Hermes, and they both have three extra articles which aid their speed, namely a travelling hat, a staff and a pair of sandals. The hat has a broad rim, which is often replaced by wings, and the sandals, which carry the god across land or sea with the rapidity of the wind, also provide wings at his ankles. The staff is sometimes depicted with two ribbons attached to it, which show the speed of travel as they flow through the air. Often these ribbons form into snakes intertwining along and it becomes the staff, becoming the caduceus symbol of the healing arts used by heal. ers and physicians to this day. Mercurius and Hermes were heralds of the gods, and they gave the qualities of eloquence, heraldry, inventiveness and cunning to the lives of men. They taught the arts of cultivation and hazel and flying, and were regarded as gods of the roads who offered protection to travellers.

Thus the spirit of the hazel is strongly aligned to speed through the families an air as well as through water, and in its legendary links with the sacred much with the salmon we see possibly the birth of both these elemental associations, for salmon swim exceedingly fast in water and then leave the waters in mighty leaps, appearing to fly through the air.

The shoots and twigs of hazel have the power to show where water is flowing underground and have been used throughout time for dowsing. Cornish people still use hazel to dowse for mineral veins as well as for water, though they stress that they do not have success without help from the piskies (Cornish faeries). Before the seventeenth century hazel rods were used to discover the whereabouts of thieves, murderers and treasure, and in France they were used for beating the bounds, i.e., boundaries of a community, so they did not fall into neglect.

In Wales supple hazel twigs were woven into 'wishing-caps' which granted the desire of the wearer. Hazel hats were also used by sailors when they had to weather hard storms at sea, for it was believed that they gained magical protection from them. Pilgrims' staffs were made food for co from hazel and so attached did the owners become to them that they were buried alongside them after death.

In ancient days hazel was plentiful in Scotland, for the name Caledonia comes from Cal Dun, which means 'Hill of Hazel'. Also possibly born in that land was the Hallowe'en hazelnuts with the names of lovers and placing them in the hot embers of a fire. If the nuts burn quietly side by side the lovers are faithful, but if one nut moves away the relationship is seen as ill-fated as one of the lovers is faithless. Aengus, the Celtic god of love, carried a hazel wand.

In Anglo-Saxon England swineherds used 'haesel' rods to control their animals, and it is thought that the name passed from the rod to the tree and it became known as hazel, rather than Cal or Coll. Haslemere in Surrey is a very evocative place-name, linking both basle, 'hazel', and mere, 'a pool' or 'the sea'. This implies a connection between hazel and the creatures of the deep sea, which emphasizes the Druidic associations of hazel and the salmon. No doubt Haslemere was named for its inspira- tional atmosphere, for many well known artists and poets have chosen to live and work there. The area also has strong associations with musical families and great recitals were played on antique instruments much the creative hazel energy, fully captured in an ancient place-name.” - from Tree Wisdom: The definitive guidebook to the myth, folklore and healing power of Trees By Jacqueline Memory Paterson

Ancient Celtic deities which represent the qualities of Coll are Mannanan Mac Lir and Brighid, ‘goddess of inspiration’.

The Gael equated hazelnuts with concentrated wisdom and poetic inspiration, as is suggested by the similarity between the Gaelic word for these nuts, cno, and the word for wisdom, cnocach.

There are several variations on an ancient tale that nine hazel trees grew around a sacred pool, dropping nuts into the water to be eaten by some salmon (a fish revered by Druids) which thereby absorbed the wisdom. The number of bright spots on the salmon were said to indicate how many nuts they had eaten.

The nine hazels that hang over the well represent wisdom, inspiration, and poetry. The trees put forth leaves, flowers, and nuts simultaneously, which fall into the water to be eaten by the salmon of wisdom who swim in the well. For every nut a salmon eats, it develops a spot (possibly a reference to a lost series of initiations or poetic grades) and any person who eats one of these magical salmon will become wise. The waters of the well develop bubbles of inspiration from the dropping of the nuts that flow out to be drunk by all people of arts (áes dána).

In rivers there is a mysterious reverse current, which salmon utilize in their ascent of waterfalls and rapids. The salmon of wisdom who venture out into the great sea of life unerringly return to the Source, an inspiring feat for any seeker of wisdom. This process is related to the Druidic art of going within to find the answer to a problem.16

The tenth-century encyclopedia of Irish oral tradition, Sanas Cormac (Cormac's Glossary), refers to caill crinmón, "the hazels of scientific composition," from which a new composition breaks out. Hazel symbolizes the hard work of attaining knowledge through breaking the hard shell to get at the sweet meat inside.

Ancient Druids and early Irish bishops carried hazel wands.

The hero Finn mac Cumhaill gained his prophetic powers wisdom by eating a salmon of wisdom that had fed on the hazelnuts that dropped into the Well of Segais. This happened when Finn was a young apprentice.

In an Irish variation of this legend, one salmon was the recipient of all these magical nuts. A Druid master, in his bid to become all-knowing, caught the salmon and instructed his pupil to cook the fish but not to eat any of it. However in the process, hot juice from the cooking fish spattered onto the apprentice’s thumb, which he instinctively thrust into his mouth to cool, thereby imbibing the fish’s wisdom. This lad was called Fionn Mac Cumhail and went on to become one of the most heroic leaders in Irish mythology.

The Gaelic word for hazel is Coll. It appears frequently in placenames in the west of Scotland, such as the Isle of Coll and Bar Calltuin in Appin, both in Argyll-shire where the tree and its eponymous placenames are the most common. It also appears in the name of Clan Colquhoun whose clan badge is the hazel. The English name for the tree and its nut is derived from the Anglo-Saxon haesel knut, haesel meaning cap or hat, thus referring to the cap of leaves on the nut on the tree.

Hazel trees frequently grow as a clump of slender trunks, and when they do adopt a one-trunk-and-canopy tree shape, they readily respond to coppicing, a practice which can actually extend and even double the lifespan of a hazel. Either way, people have put the young shoots or whips and the thin trunks to a variety of uses.

Hazel has long been a favourite wood from which to make staffs, whether for ritual Druidic use, for medieval self defence, as staffs favoured by pilgrims, or to make shepherds crooks and everyday walking sticks. In the case of the latter two, the pliancy of the hazel’s wood was used to bend the stems into the required shape, though it was also customary to bend the hazel shoots when still on the tree to ‘grow’ the bend into a crook or walking stick. The wood readily splits lengthways and bends easily, even right back on itself, which makes it ideal for weaving wattle hurdles for use as fencing or as medieval house walls when daubed with mud and lime. Hazel stakes bent to a U-shape were also used to hold down thatch on roofs. Like willow, young coppiced hazel shoots were used to weave a variety of baskets and other containers. Forked twigs of hazel were also favoured by diviners, especially for finding water. Hazel leaves are usually the earliest native ones to appear in spring and often the last to fall in autumn, and were fed to cattle as fodder. There was also a belief that they could increase a cow’s milk yield.